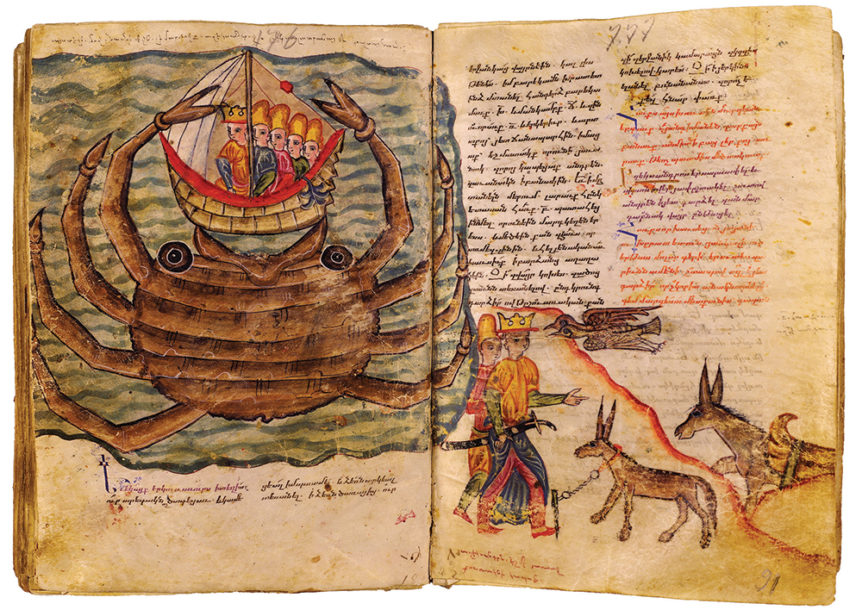

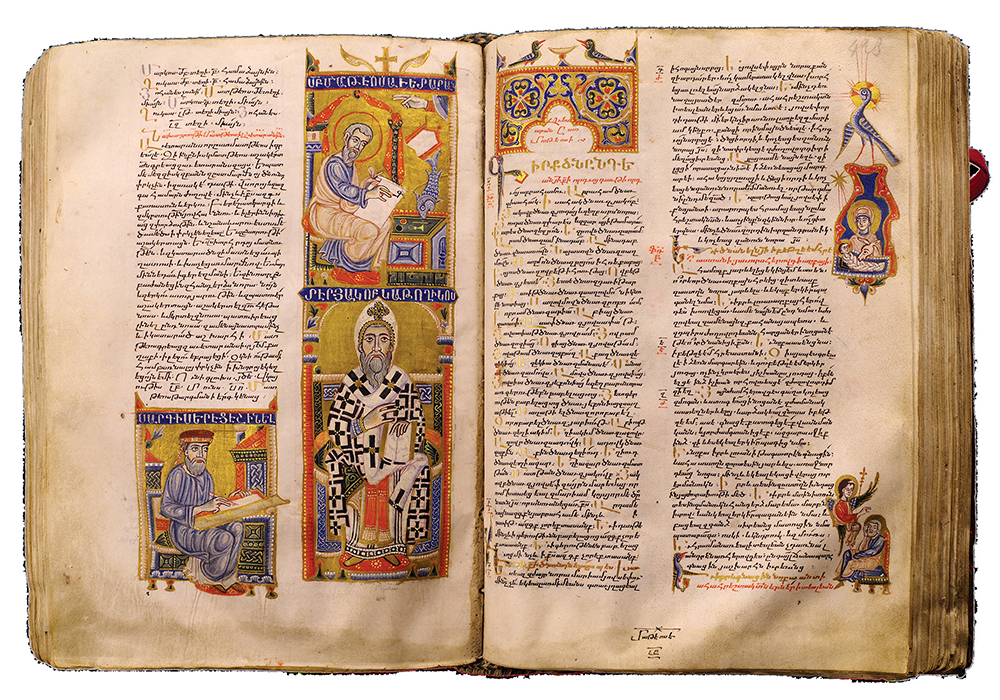

Fig. 1. Spread in a copy of the Alexander Romance, Rome and unknown location, sixteenth century. Illuminated by Zak‘ariay of Gnunik‘ and Hakob of Julfa; scribed by Zak‘ariay of Gnunik‘. Tempera and ink on parchment, 9 1/2 by 7 inches (page). “Matenadaran” Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute-Museum of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan, Armenia; except as noted, photography is by Hrair Hawk Khatcherian and Lilit Khachatryan.

A great and ancient culture stands revealed in a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The show is simply titled Armenia!, which is good, because it is indeed about Armenia! Not since the Met’s massive Indian exhibition of 1985, titled India!, has the exclamation point been used quite so energetically in a museum context. But if that punctuational gambit seemed to make sense in the context of the storied sub-continent, its present application to a little-known republic in the Southern Caucasus is more likely to provoke a “?” from the general run of museumgoers, many of whom will approach this latest show in a state of nearly total ignorance.

Now, ignorance is a much-underrated aspect of human experience. Although few people come out publicly in favor of it, nevertheless it has two things in its favor, at least as regards a museum exhibition. The first, paradoxically, is that it is so easily remedied. Assuming you are already well-versed in, say, impressionism, it would take you weeks of applied study to increase your knowledge of that field by even ten percent. But in the case of Armenia, many a visitor will emerge from an hour at the present exhibition with a tenfold increase in his knowledge of the country, starting, perhaps, with the revelation that the place exists, and then with the ability to locate it on a map.

Fig. 2. Arm reliquary of Saint Sahak Partev made in the Lake Van region (Vaspurakan), late seventeenth–early eighteenth century. Silver and silver gilt with colored gemstones and filigree work; height 16 1/8, width 3 inches. Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, Vagharshapat, Armenia.

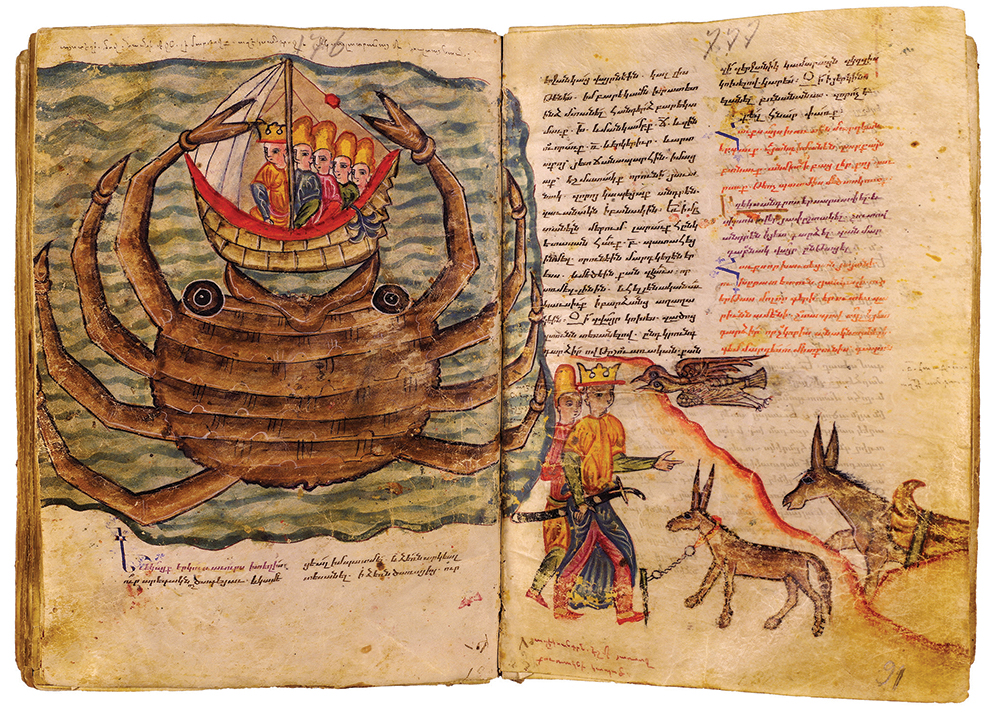

Fig. 4. Carved door from the Church of the Holy Apostles (Surb Arak‘elots‘), Monastery of Sevan (Sevanavank‘), Lake Sevan, 1486. Walnut; height 73 ¼, width 38 5/8, depth 7 7/8 inches. History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan.

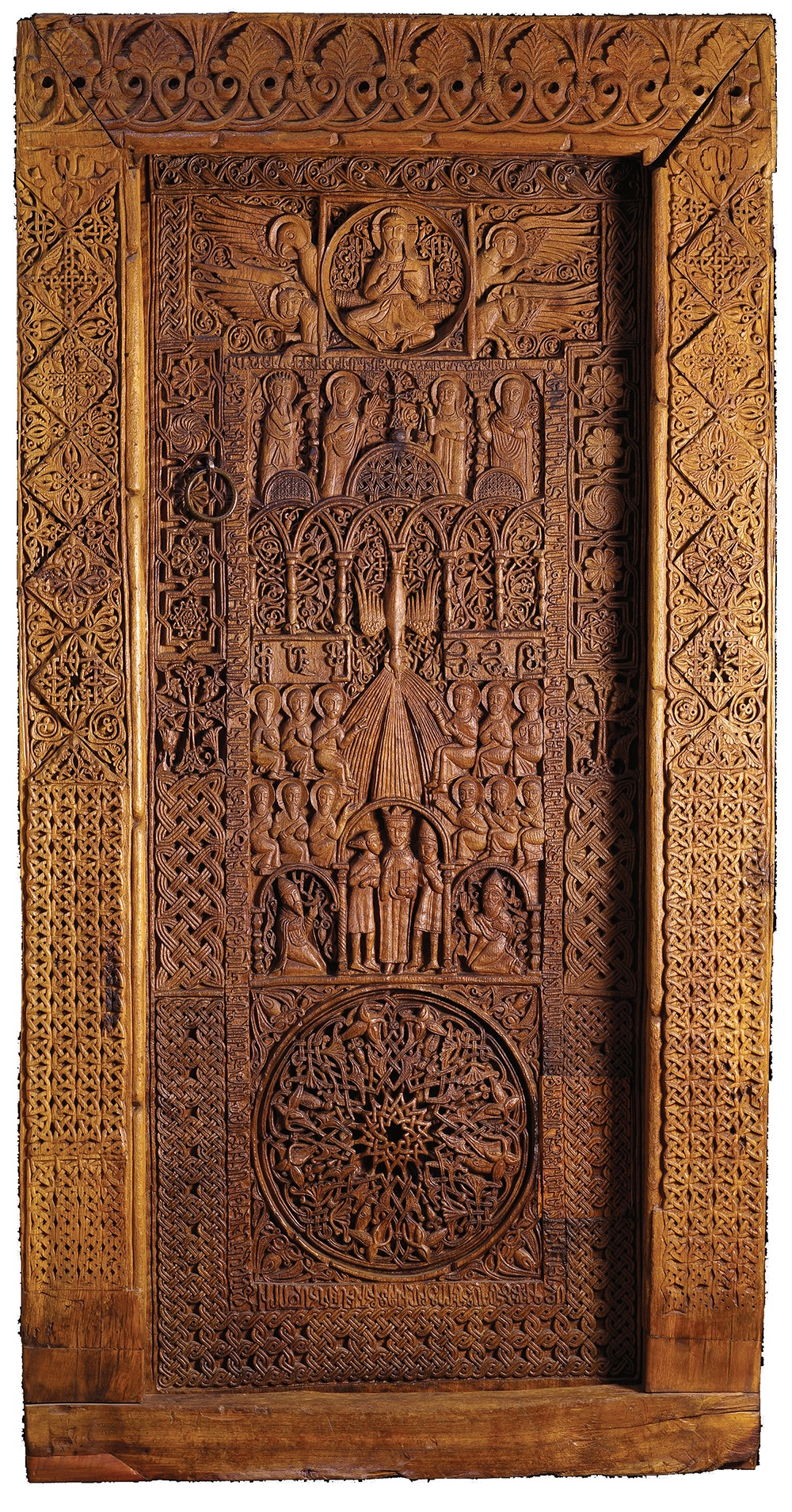

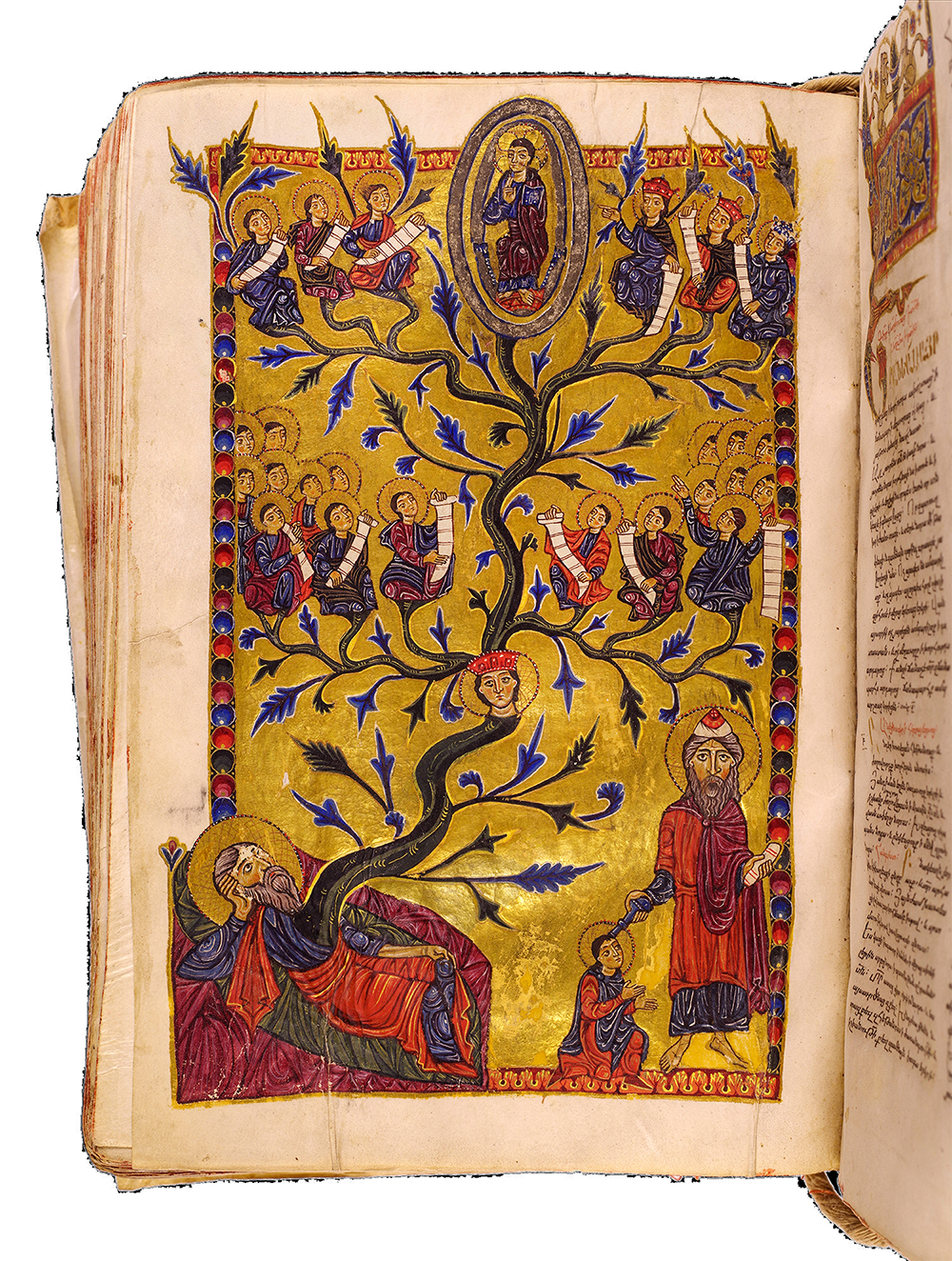

Fig. 3. Bible of Yerevan made in the city of Sis (now Kozan), 1338. Illuminated and partially scribed by Sargis Pidzak. 546 folios; ink, tempera, and gold on parchment; 9 ¼ by 6 ¼ inches (page). “Matenadaran” Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute- Museum of Ancient Manuscripts.

But there is an even greater charm to the present show. It is, of course, a scholarly exposition of an entirely worthy subject, one that rewards our committed attention. And if you can bring that sort of attention to the show, so much the better. But realistically, most visitors will not be inclined to approach the display in that way and perhaps they should not even try. For there is a second virtue of ignorance, at least as regards a museum exhibition. In a case like Armenia, which is so far removed from the average art lover’s area of interest or understanding, the experience can be liberating. Emancipated from the obligation to digest the contents of each label, to understand each object’s relation to all the others, the viewer can float freely through the galleries, responsive only to the delighted promptings of his two eyes.

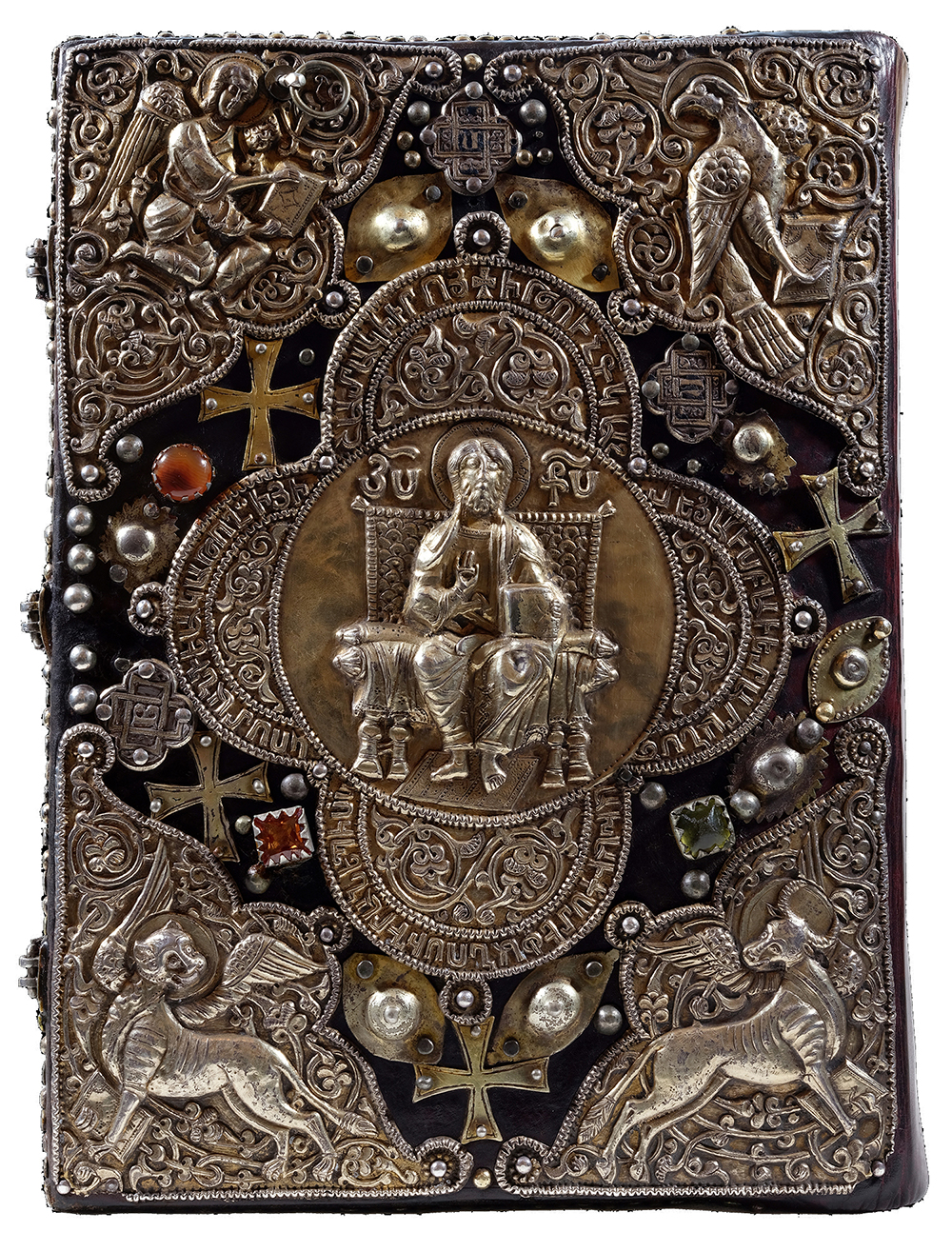

Fig. 6. Bardzrberd Gospel Book cover made at the fortress Hromkla by Vardan, 1254. Gilded-silver sheet, repoussé and chased; pierced bosses, 10 5/8 by 8 ¼ inches. Holy See of Cicilia, Antelias, Lebanon; photograph courtesy of Holy See of Cilicia.

And, in that context, Armenia! has much to offer, with its display of nearly 150 works, stretching from primarily late antiquity to the eighteenth century. There is a mirage-like instability to this nation’s historical and cultural profile, and that is not the least of its charms. It seems at once familiar and remote, part of the consoling mainstream of medieval art—with all the gospel manuscripts, silver reliquaries, and ecclesiastical robes that are so familiar to seasoned museumgoers— and yet also something born of a different tradition altogether, ancient, rugged, and unfathomable. It shares this quality with the art of Byzantium, by which it was greatly influenced. Both civilizations stood at a crossroads between East and West, inspired in equal measure by the formal traditions of Greece and Rome and by those of Persia.

Fig. 5. Folio in a Gospel Book made at the Monastery of Argelan, Berkri, Lake Van region (Vaspurakan), 1294. Illuminated by Khach‘er; scribed by Hakob. Tempera and ink on parchment; 12 3/8 by 10 3/8 inches. “Matenadaran” Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute-Museum of Ancient Manuscripts.

Armenia can also claim one of the most beautiful alphabets in the world, a cross between Syriac and Greek: its letters race across the page with an air of disciplined regimentation, almost leaning forward in their eagerness to reach the margins of the page. A fine example is a folio from a copy of the Alexander Romance sixteenth-century, whose red, black, and purple letters appear beside the curious image of a giant crab about to swallow up the ship that carries Alexander (Fig. 1). In another illustration of the Alexander legend from 1536, we see the emperor’s horse Bucephalus looking more like a simurgh—a mythical Persian bird—than like your average equid. The manner of its depiction calls to mind the silverwork of the Sassanian Empire, and even though that empire passed into extinction nearly a thousand years before the manuscript was created, it nevertheless provides graphic evidence of the persistence and longevity of formal motifs in this part of the world.

Most of the art on view at the Met does not manifest quite so vigorous a strain of pagan influence. At a time when the Romans (and in a sense the Byzantines) were still persecuting Christians, the Kingdom of Armenia, under Tiridates III, became the first nation to convert en masse to the new faith in 301, about a decade before the conversion of Constantine the Great. Rising in the shadow of Mount Ararat, on whose famously flattened summit Noah’s ark is said to have come to rest, Armenia is defined by its church, one of the six autocephalous or self-governed churches of Oriental Orthodoxy, which is related, but not identical, to Greek and Russian Orthodoxy.

Fig. 7. Folio from a Bible made at the Monastery of Gladzor, Siwnik‘, 1318. Illuminated by T‘oros of Taron; scribed by Step‘anos, Kiwrake, and Yoghannes Yerznkats‘l. Ink, pigments, and gold on parchment, 10 ¼ by 7 1/8 inches. “Matenadaran” Mesrop Mashtots‘ Institute- Museum of Ancient Manuscripts.

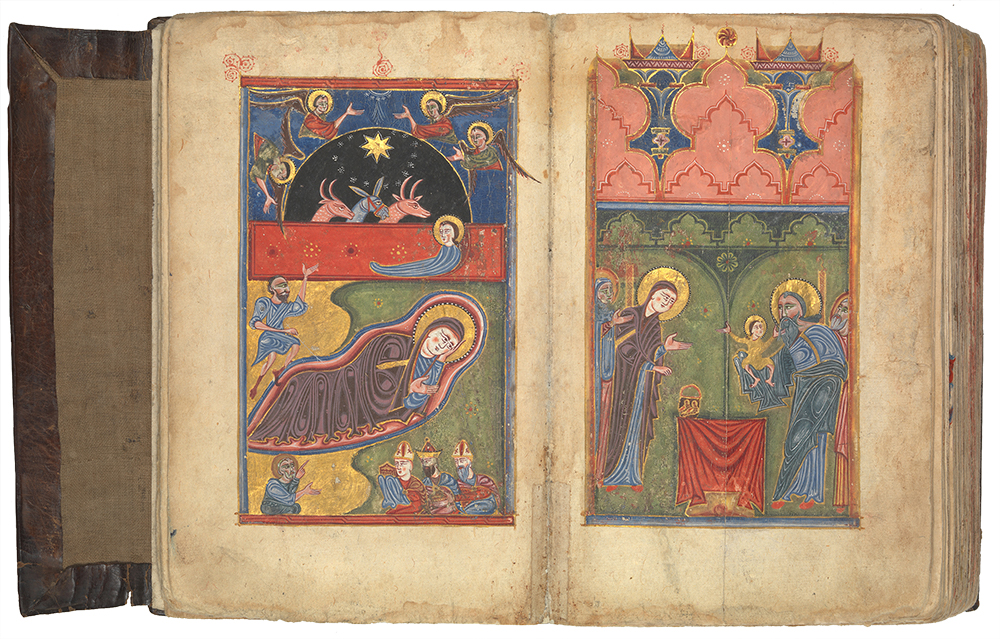

The range of styles visible in the Armenian religious manuscripts in the exhibition is striking. One leaf from a Gospel of about 1300 from the Lake Van region, depicting the baptism of Christ, exhibits the childlike simplicity of Jean Dubuffet allied to the pulsating religious intensity of Georges Rouault (Fig. 5). Far flashier is the Khizan style of the next century, in which the full spectrum of the rainbow has been invoked in the depiction of a nativity of around 1435 (Fig. 8). It seems quite likely that the artist has gotten his hands on a French miniature of the time, but, if he preserves its general form, he has completely distorted its spirit. Such distortion survives into the next century, when the painters of the Julfa style throw aside all sense of naturalism to depict a bugeyed Creator, his head surrounded by stars and a radiant halo as he invents the universe. It is no less evident in the nearly contemporary depiction of God the Father from Isfahan: what looks like a laser beam shoots from his mouth, as he finds himself surrounded in electric protoplasm.

Fig. 8. Gospel Book made at the Monastery of Saint George the General, Mokk‘, Khizan, 1434– 1435. Illuminated by Khach‘atur and an anonymous artist; scribed by Margare. Ink, tempera, and gold on paper; stamped leather binding; height 11, width 7 5/8, depth 3 3/8 inches (closed). Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase with funds from various donors; photograph © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 9. Four-sided stela from the Monastery of Kharaba (Kharabavank‘), southern slope of Aragats, Ashtarak, 300s–400s. Tuff; height 69 5/8, width 15 ¾, depth 15 ¾ inches. History Museum of Armenia.

Sculpture is hardly absent from this show, as seen in the deep carving of its stone khachkars, or crosses, as well as in such inscrutable objects as a silver arm reliquary of Saint Sahak Partev (Fig. 2). But what may be the crowning achievement of Armenian visual culture can be suggested in this exhibition only by photographs. I speak of its wondrous churches with their strong mural presence and their impressive massing, which takes the place of ornament and has no need of it. Often monasteries that, by definition, occupy the remote places of the world, seem doubly remote: they are about as far removed from the geographical centers of our modern world as it is possible to be. At the same time, their ashlar walls, tuff shingles, and stone vaulted ceilings enshrine certain values and ideals, those of reticence and removal, that are so alien to our modern experience that they seem to reach us, not only from a very different age, but from an entirely different planet.

Armenia! is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from September 22 through January 13, 2019. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by the museum.