We spoke with Joel Bohy, a specialist in historic arms and militaria for Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers, about his vast and varied knowledge of military history and material culture, his expeditions to archaeological digs at battlefields, and his talent for making reproduction arms and uniforms.

Joel Bohy marching with Captain David Brown’s company of Concord minutemen in a reenactment at the North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts.

The Magazine ANTIQUES: Could you tell me what first sparked your interest in this material?

Joel Bohy: I grew up in Concord, Massachusetts, and obviously you know what happened there. I was infatuated with the history. I would spend any free time in the library, pulling out documents, and going to local historical sites and collections and trying to find objects that might relate to the start of the American Revolution, and then verify them through research. I would go to a small museum and see something that was, I knew, a bayonet from the Spanish- American War era. They were saying it was captured on April 19, 1775, and I would say, “well, no, actually . . .” Through that, I would learn a lot more, and so would the museum.

A 1756 British Long Land-pattern musket linked to the 43rd Regiment of Foot. Photograph courtesy of Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers, Boston, Massachusetts.

TMA: How did you begin collecting?

JB: Through all this research, I began collecting. Obviously, as a youngster, I couldn’t afford American Revolutionary War objects, though that was my main passion. I collected things from the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. When I was a child, there were many, many World War II veterans still around. I would sit and talk with them about their experiences. I would also go to militaria shows, and pick up artifacts or objects to complete uniforms and equipment that would have been worn and used by the common soldier during those wars.

A detail of the 1756 British Long Land-pattern musket. Photograph courtesy of Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers, Boston, Massachusetts.

TMA: What is in your personal collection now? And what would you say is your most prized possession?

JB: Well, it’s morphed a little bit since I started working at Skinner. I see so much of this material that I almost stopped collecting. I didn’t need to anymore. In a way, it was the thrill of the chase to find these objects and own them. But through working here and being around it so much, I don’t have to own them.

And then through an archaeological dig I was doing in Minute Man National Historical Park near Concord, I met some other battlefield archaeologists, and I said: “You know, wouldn’t it be great to do some ballistics on how these things actually functioned and their muzzle velocities and how that impacted different battles?” Then I started to have custom-built reproductions of American Revolutionary War muskets and fowlers made—different types of arms that would have been carried.

Two years ago we did the first study and published it. We just recently finished working on the second part of the study down in Georgia, where we had a range set up to study what happens when these weapons are fired and what they can and cannot actually do. Now I collect stuff to study what it does, and use what I collect for research.

A detail of the 1756 British Long Land-pattern musket. Photograph courtesy of Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers, Boston, Massachusetts.

TMA: Your expertise runs the gamut. Is it that once you start studying the period, you become interested in many different aspects of material culture?

JB: I keep going back to this, because I was raised in Concord. You want to understand what these farmers, who were training to be militia and minutemen, used in their daily lives before they became citizen soldiers, and then during the time they were citizen soldiers. At least for me, I want to go through and study what, for example, they cooked with—and then that transfers to archaeology. What we find at these sites tells us what they used in their homes.

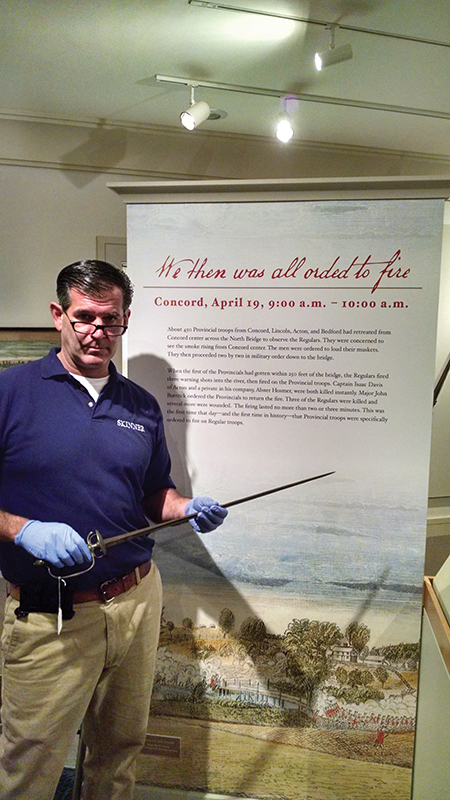

Bohy holding Major John Buttrick’s sword while installing The Shot Heard Round the World: April 19, 1775, a 2014 exhibition at the Concord Museum. The sword was carried at the North Bridge battle on April 19, 1775. Photograph by Robert Cheney.

TMA: So you’re trying to create a full picture of that period?

JB: Exactly. Trying to, the best we can. When it comes to the American Revolution, we have some written works, some paintings, and some artifacts. For the Civil War, there is much more material—because there were millions of soldiers and there was also photography by then. As you get up to World War II, it is a lot easier to study. With the American Revolutionary War, and even prior to that, the French and Indian War, it is a heck of a lot harder because there is not that much out there. And that for me is kind of the fun part of it.

The 1945 Willys MB jeep restored by Bohy. Photograph by Joel Bohy.

TMA: I understand you participate in historical reenactments.

JB: Well, that’s also part of learning. In one case, I worked on the filming of the movie Gettysburg as an extra. I was always fascinated with the Civil War too, and had ancestors on both sides and I wanted to learn more about that. It wasn’t necessarily the filming part of it, but the marching. I was just trying to get the experience.

Primary documentation of the life of a Civil War soldier became a passion, too. I would go to museums and pull out uniforms and study and then replicate them, so that we could try to get a really good picture of how these people lived.

TMA: I also hear you drive around in a vintage military jeep.

JB: I do [chuckles]. I don’t know whether you ever saw the TV show The Rat Patrol. As a little kid, I used to watch it. The show was about two jeep squads roaming around fighting the Germans in North Africa, and I was fascinated with the jeeps. I ended up purchasing one and then spent about ten years restoring it—a 1945 Willys MB. I don’t drive it every day, but whenever I can I get in that thing, start it up, and take it for a spin. It starts up every time. I don’t have that luck with my modern car.

Bohy at seven years old at the North Bridge Visitor Center, Minute Man National Historical Park, in a photograph of 1973. Photograph by David Bohy.

TMA: Did you restore it yourself?

JB: Well, I can’t say I did it all myself. I had a lot of help. I have friends who were great at different mechanical work, or body painting, and I did a lot of the work along with them. There is a master parts list for the jeep. Each bolt on the ’45 Willys is marked with an “EC.” I went to shows and picked up every bolt, and blasted them, and painted them, so that all the bolts you see on that jeep are the correct size and marked properly. I wanted everything to be correct.

It is so much fun to drive around. I used to use the jeep on Memorial Day to take around all the World War II veterans who couldn’t walk through the parade. That was one of the highlights of the year for me. I can get four or five vets jammed into that thing, and—listening to their stories, and hearing them laugh—it just made it all worthwhile to put all the time and effort and money into the thing.