Two years ago this magazine published an article by Bernard L. Herman on Ronald Lockett, one of the artists included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibition History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift. We gave the article a deliberately provocative title: “Let’s Just Call It Art.” Two years is not much in the long arc of art history, and yet the works of Lockett and the other artists in the exhibition have now arrived at the Met without the usual diminishing labels of outsider, folk, self-taught, outlier, or whatever. Some of these artists are living, others dead. All are African American, southern, poor, mostly rural, and mostly unknown, and yet they are here in the front line of the art world on their artistic distinction alone. How did this happen? I will get to that, but first, the art.

Fig. 1. History Refused to Die by Thornton Dial (1928–2016), 2004. Okra stalks and roots, clothing, collaged drawings, tin, wire, steel, Masonite, steel chain, enamel, and spray paint; height 102, width 87, depth 23 inches. All objects are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation, 2014, from the William S. Arnett Collection.

Of the fifty-seven works given to the Met by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2014, thirty are on display in two beautifully installed galleries. There are six assemblages and three drawings by Thornton Dial, who, like the quilters from Gee’s Bend also represented here, already has a following in the art world. But when you see his pieces and theirs in conversation with each other and with assemblages by lesser-known figures like Lockett, Joe Minter, and Lonnie Holley, deeper and more soulful connections begin to emerge. All these works can be said to be about what they are made of: scrap metal, scrap wood, old work clothes, okra stalks, twine, toy cars, barbed wire, pine straw, electric cord, and so forth. For artists who have seen into and beyond what surrounds them, the things of this world have more than one function. It’s a liberating point of view.

Fig. 2. Victory in Iraq by Dial, 2004. Barbed wire, steel, clothing, tin, electric wire, wheels, stuffed animals, toy cars and figurines, plastic spoons, mannequin head, woods, basket, oil, enamel, spray paint, and Splash Zone compound on canvas on wood; height 83 ½, width 135, depth 16 inches.

If Jackson Pollock surprised the world in the way he threw down paint, Dial, Lockett, Holley, Loretta Pettway, Annie Mae Young, and others astonish in the deft way they have retrieved, reassembled, and reimagined the world. Many of the pieces have evocative titles like Dial’s masterpiece that has given the exhibition its name: History Refused to Die. Others refer to events such as the Oklahoma City bombing, the war in Iraq, or years of unpaid labor. Some, like many of the quilts, do not have titles. But they are all the work of master improvisers and in that sense share something with African-American music, from blues and jazz to hip-hop. Much has been written—and much more will be after this exhibition and others like it—to describe the continuity in African- American culture, whether isolated and rural or urbane and public.

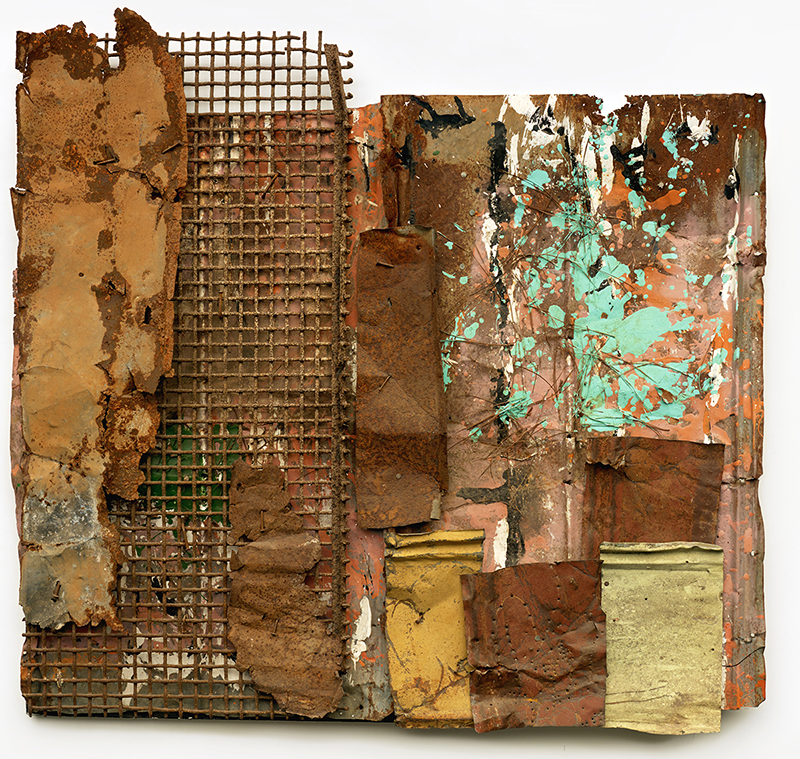

Fig. 3. The Enemy Amongst Us by Ronald Lockett (1965–1998), 1995. Paint, pine straw, metal grate, tin, and nails on wood; height 50, width 53, depth 3 inches.

The art from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation flourished in African-American communities in the South from roughly the 1960s to early in this century. As Zora Neale Hurston explained many decades ago when she was collecting folktales for Mules and Men, the real story of art in such isolated communities is not one of poverty and racism, but of survival, creativity, and imagination. This art is not defined by or a response to white oppression, even if those dark shadows occasionally fall across it.

Fig. 4. African Mask by Lonnie Holley (1950–), 2004. Automobile tires, welder’s mask, electrical outlets, electrical cord, door lock, and lace fabric; height 35 ¾, width 30 ½, depth 9 ¼ inches.

One person who recognized the power and creative autonomy in the rural art of the South was William S. Arnett, prime mover of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Although he was born in Georgia, Arnett came to this art only in the 1980s after two decades abroad assembling, among other significant collections, one comprising the ritual arts of West and Central Africa. He may not have been the first person to approach Thornton Dial, the quilters of Gee’s Bend, and some of the others he collected, but he was the first to have both an eye sophisticated enough to know that this work belonged on a global stage and enough determination to put it there. (The inevitable allegations about Arnett’s financial dealings with artists have long since been put to rest. His generosity is well documented. See the definitive account by Paige Williams in the New Yorker, August 12 and 19, 2013.) In addition to collecting the art, Arnett established Tinwood Books for the publication of Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, two vast volumes with essays and commentary by a range of impressive figures, as well as several other books. He also amassed an archive of twenty thousand photographs, videos, oral histories, and other material, which he donated to the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Fig. 5. Grown Together in the Midst of the Foundation by Holley, 1994. Cottonwood, steel, wire, concrete, and PVC pipe; height 96 ½, width 37, depth 29 inches.

If Arnett has promoted some wayward theories about secretly coded meanings in the art, and if he has a reputation for being not only fanatical but difficult in his early dealings with museum officials, galleries, and other collectors, it is not surprising. Only an obsessive could have accomplished what he has. “Bill didn’t just march to a different drummer,” Bernie Herman tells me, “Bill was the drummer and the drum.” Fortunately, Arnett has a core of loyal friends and supporters who smoothed his way by encouraging him, in 2010, to establish the nonprofit charity Souls Grown Deep, where he would eventually place twelve hundred works from his massive collection for loans and donations.

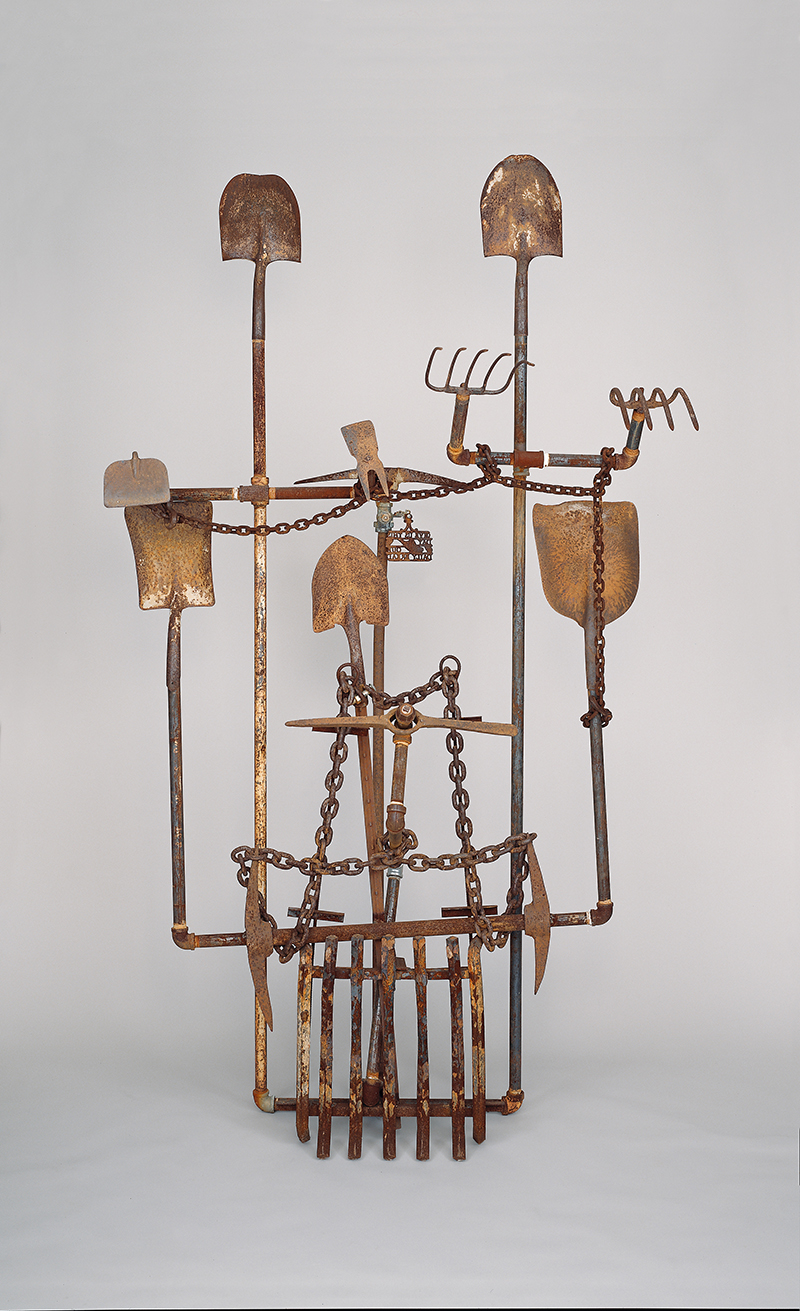

Fig. 6. Four Hundred Years of Free Labor by Joe Minter (1943–), 1995. Welded found metal and tools; height 105, width 60, depth 54 inches.

The foundation’s name is an inspired one. It comes from a line in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” a poem Langston Hughes wrote when he was only seventeen and traveling through the South to Mexico. In it he evokes the continuity of memory across history and cultures from the cradle of civilization to the present. The poem begins, “I’ve known rivers: / I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.” It ends, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” It’s a significant theme for art born in obscurity and charged with speaking both locally and globally.

Fig. 7. Work-clothes quilt by Annie Mae Young (1928–2012), 1976. Denim, corduroy, and synthetic blends, 104 ½ by 77 inches.

Among Arnett’s longtime supporters is Maxwell L. Anderson, who has known him since the 1980s, when he was director of the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta, where many of the artists in Arnett’s collection were first shown. In 2002 Anderson brought the sensationally successful Gee’s Bend Quilts exhibition to the Whitney Museum in New York when he was its director, and a Thornton Dial exhibition to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2011 during his tenure there. He is now president of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, where he, Bill Arnett’s son Harry Arnett, and the foundation’s board have overseen the distribution of artworks to, among others, the Philadelphia Museum of Art (twenty-four works), the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (thirty-four works), the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (sixty-two works), and the New Orleans Museum of Art (ten works). There will also be donations to historically black colleges and universities.

Fig. 8. Housetop variation quilt by Lola Pettway (1941–), c. 1975. Corduroy, 84 ½ by 71 inches.

But the Met was the big one, the first one, the one designed to put the art on a world stage. Michael Sellman, a New York financier with roots in the world of Bill Arnett—he and his father are trustees of Souls Grown Deep—describes the day in 2014 when a group from the Met led by Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman of Modern and Contemporary Art, was invited to Atlanta and given the run of the foundation’s warehouse. Sellman gives Wagstaff credit for seeing how important it was for the museum to have and exhibit the work of these artists. Subsequent visits from other Met curators resulted in the final selection of the fifty-seven works. They chose well; it is a splendid group and yet it is not enough. There is nothing by James “Son Ford” Thomas and only one piece by Ronald Lockett. Aleesa Alexander, a fellow in the department of modern and contemporary art who has been to the Atlanta warehouse and is an admirer of Lockett, hopes for more.

Fig. 9. Medallion quilt by Loretta Pettway (1942–), c. 1960. Synthetic knit and cotton sacking material, 81¾ by 70 inches.

In the meantime we have this exhibition and that is quite a lot. The excellent catalogue essays by Cheryl Finley, Randall R. Griffey, Amelia Peck, and Darryl Pinckney demonstrate the museum’s commitment to the art without the use of those diminishing labels—and for the most part without the invidious distinction between art and craft. We will not see the Met exhibit these works in inane pairings with a Rauschenberg or a Rothko or a Kiefer, where their accidental similarities obscure everything that makes them vital. Still, I worry about how much of the Souls Grown Deep gift will be on permanent display at the museum after the show closes. I could not get a reassuring answer, though I was told there would certainly always be one or two pieces on view. That is is not enough to tell this story and fulfill Bill Arnett’s dream, but then there are all the other museums where the diaspora of these once obscure African-American works will continue to reshape the story of American art.

History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift is on view through September 23 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.