Fig. 1. Summer Clouds by Gustave Baumann (1881–1971), 1925. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “SUMMER CLOUDS” and “III 118125” under image. Color woodcut, 10 3/4 by 9 5/8 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, purchased with funds raised by the School of American Research; photograph by Blair Clark, © New Mexico Museum of Art.

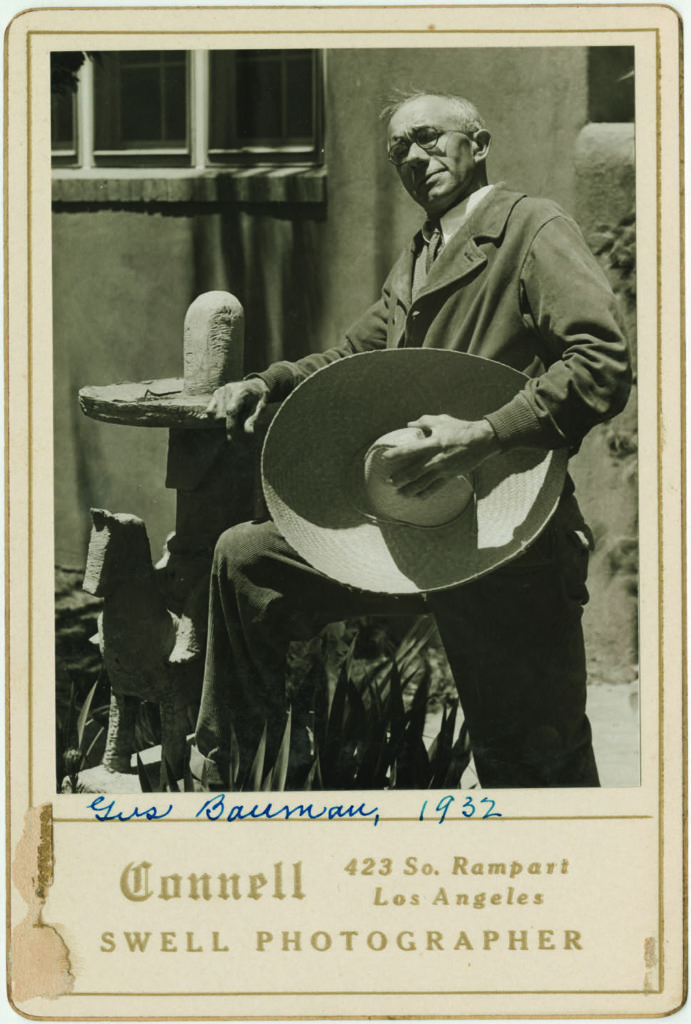

“Art is a kind of tyrant,” Gustave Baumann observed in autobiographical notes he made during the 1940s. “It came to me dressed up in wanderlust.” By 1918, at age thirty-seven, the artist had already wandered far: as a child, with his family from their native Germany to a new home in Chicago; as he matured, to places as diverse as rural Indiana, Munich, San Francisco, upstate New York, and Provincetown, Massachusetts. When Baumann arrived in Santa Fe that autumn, he intended to spend just a few days there before heading home to Chicago, or perhaps moving on to New York City. He had no clue he’d live the rest of his life there and become the artist who, arguably more than any other, made the beauties of New Mexico’s bright skies and vivid landscape known to the wider world. Baumann was a master of color woodblock printing, and would create hundreds of works in that medium during his long career. He was also a classic American immigrant success story. His family moved from Magdeburg in Saxony to Chicago in 1891. When Baumann’s father left the family home about six years later, young Gustave quit school in the eighth grade, and apprenticed at an engraving firm. He took night classes at the Art Institute school, and went to work as a commercial artist—creating calendars, labels, and advertisements that featured “an occasional fried egg to enhance sliced bacon and stimulate ‘buy appeal’ in the minds of magazine readers,” in his wry recollection.

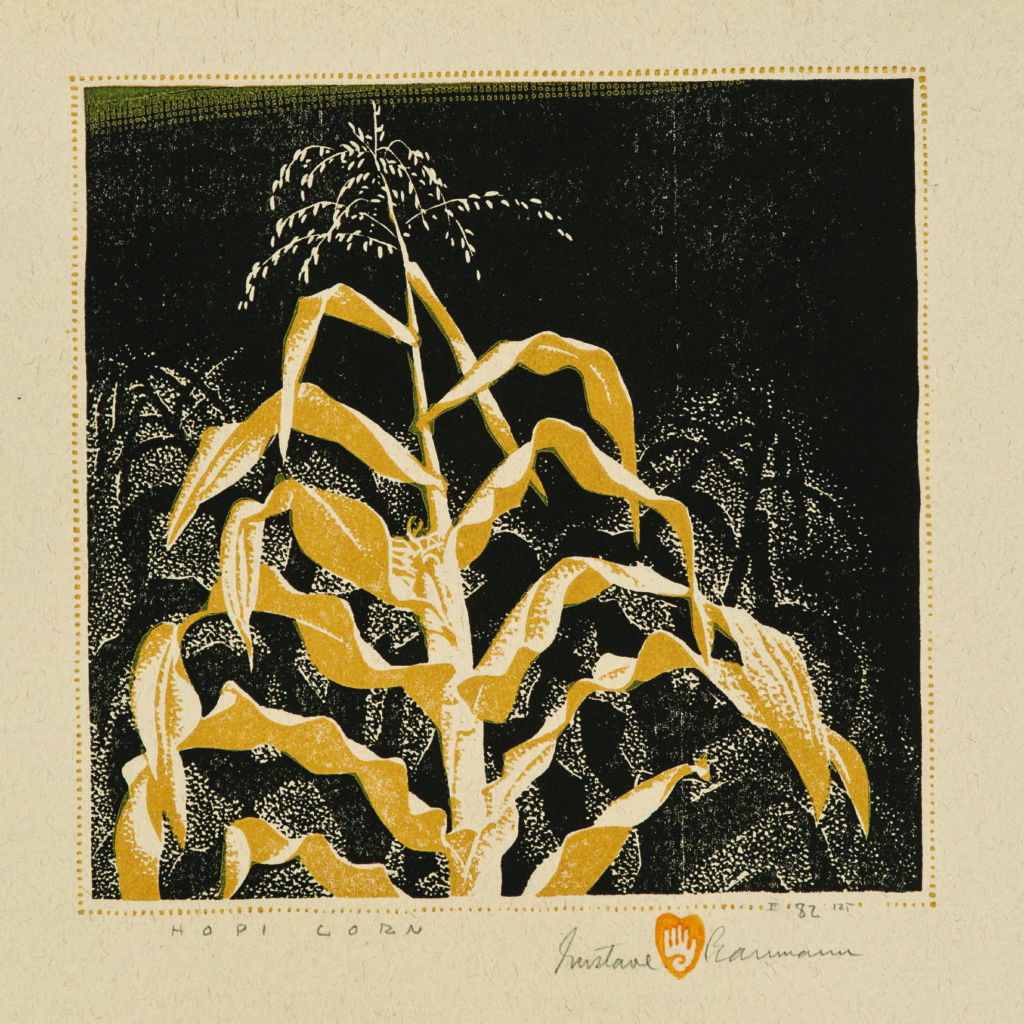

Fig. 2. Hopi Corn, 1938. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “HOPI CORN” AND “I 82 125” under image. Color woodcut, 8 1/8 by 8 1/4 inches.

He saved his earnings and in 1904 traveled to Munich, where he spent more than a year studying at the Königliche Kunstgewerbeschule—Royal School of Applied Arts—and mastering the rigorous techniques of color woodblock printing. Baumann resumed his commercial work when he returned to the Midwest, but crafted woodcuts in his off hours and had his color prints exhibited for the first time in 1910 at the Art Institute. That summer he visited Brown County, Indiana, an affordable, bucolic spot popular among artists and writers, and—while maintaining a studio in Chicago— would live there full time for the next six years. Meantime, Baumann’s complex and beguiling woodblock prints of verdant rural scenes and abundantly leafy trees began to be published and exhibited widely: his work was included in the 1911 Paris Salon, and presented in his first solo show at the John Herron Institute of Indianapolis in 1913. Baumann then won the gold medal for printmaking at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

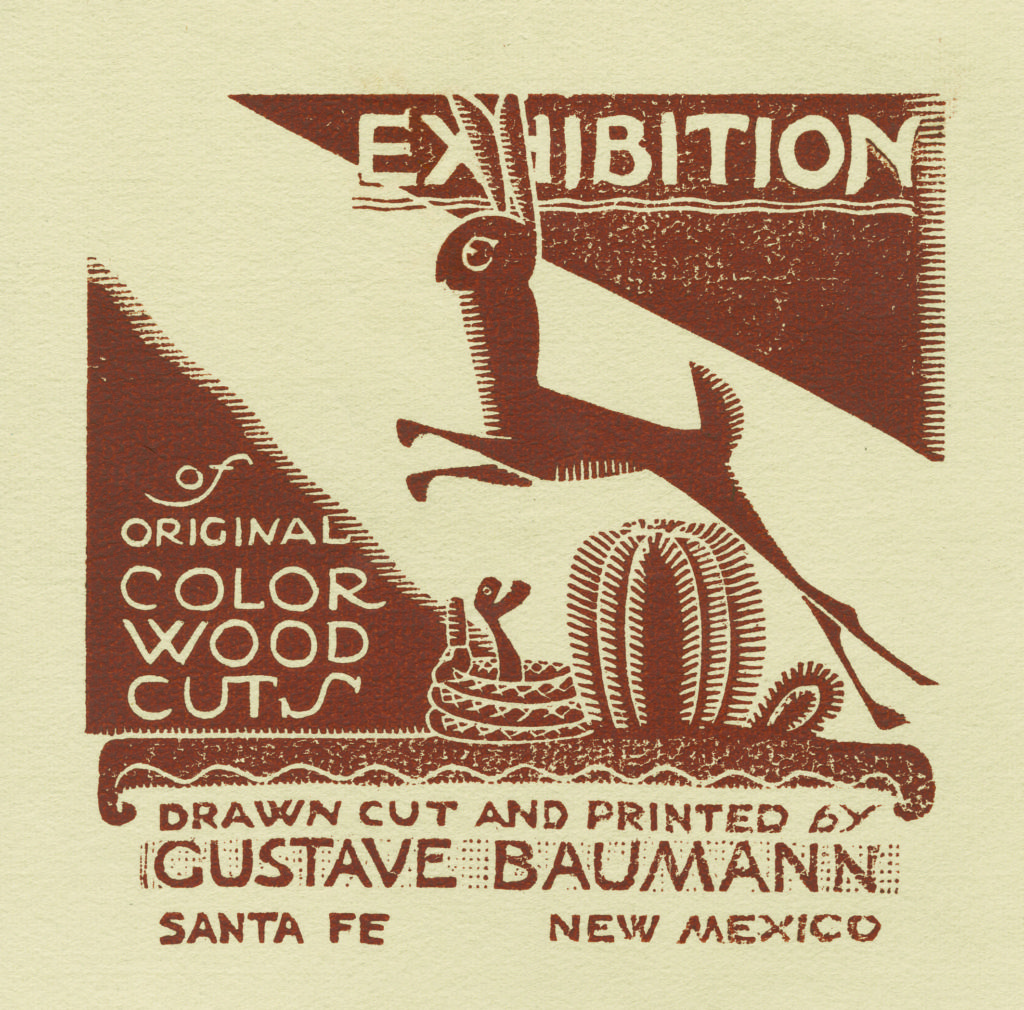

Fig. 3. Poster for an exhibitionof Baumann’s works, c. 1918. Woodcut, 8 3 /8 by 8 ½ inches. Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, Santa Fe, Baumann Collection; photograph courtesy of the Ann Baumann Trust.

He joined two Chicago friends—painter Victor Higgins and printmaker Walter Ufer—for the 1918 season in the burgeoning summer art colony at Taos. While dazzled by the high desert light, vast terrain, and intense colors of New Mexico, Baumann felt there was too much emphasis in Taos on the social whirl. That autumn, he planned to head home by way of Santa Fe, where a traveling exhibition of his woodblock prints had recently opened at the city’s new Art Gallery of the Museum of New Mexico— now the New Mexico Museum of Art.

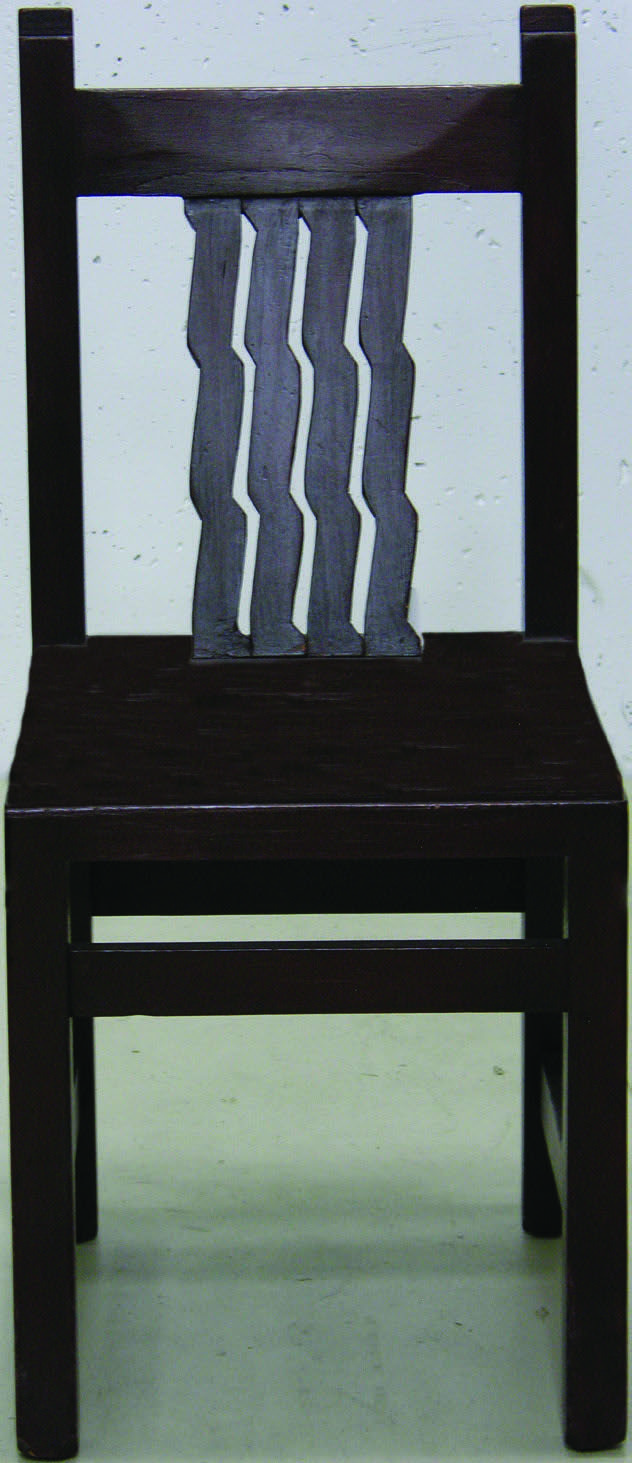

Fig. 4. Carved chair by Baumann, c. 1930. Wood and paint; height 36, width 15 ½, depth 18 ½ inches. Gift of E. Catherine Rayne.

A curator, Paul Walter—a fellow German immigrant—hit it off with Baumann and invited him to take part in the museum’s ambitious visiting artist program. When the artist insisted he had to go home and earn a living, Walter offered to arrange a line of credit for him at the bank, along with free studio space: a workroom facing the enclosed patio of the four-hundred-year-old Palace of the Governors, where the museum was located at the time. Baumann accepted, but requested instead to work in the basement. “Baumann was very private in his work,” explains Tom Leech, curator and director of the Palace Press, a museum of print history and a working publishing house. “He said that he was a craftsman by choice and an artist by accident. While he was working here, he also designed and built furniture for the museum.”

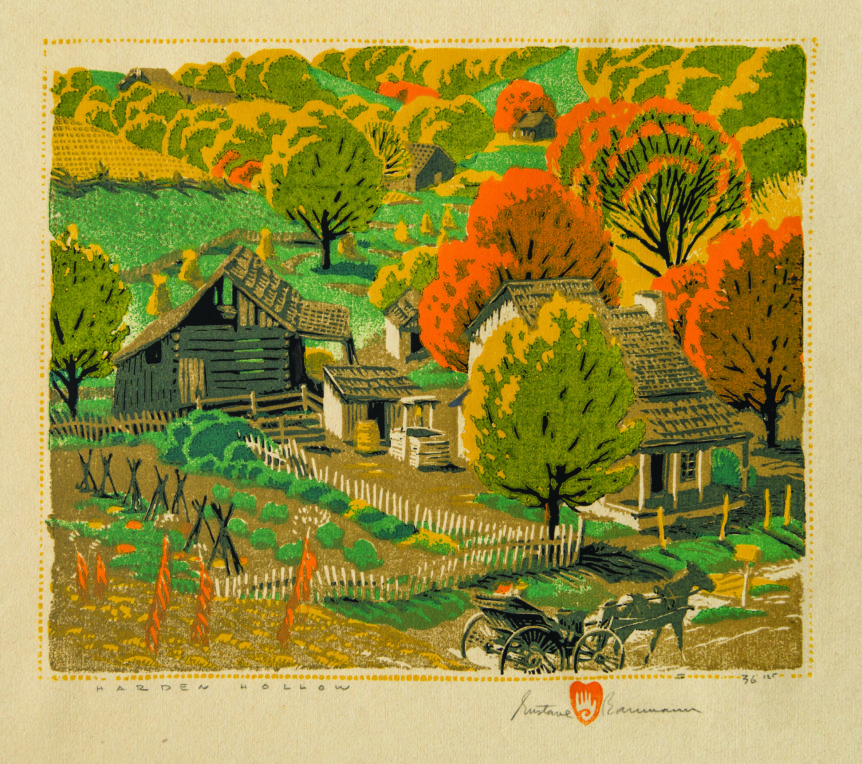

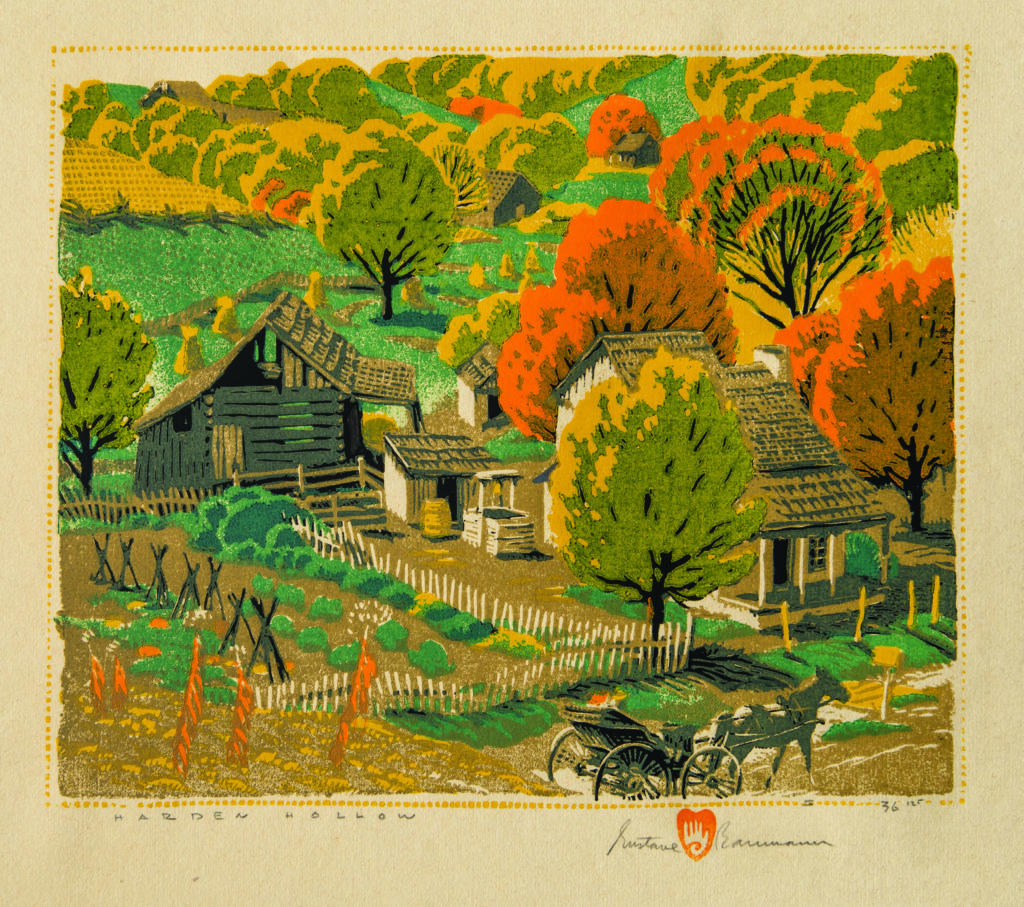

Fig. 5. Harden Hollow, 1927. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “HARDEN HOLLOW” and “II 36 125” under image. Color woodcut, 9 1/2 by 11 1/2 inches.

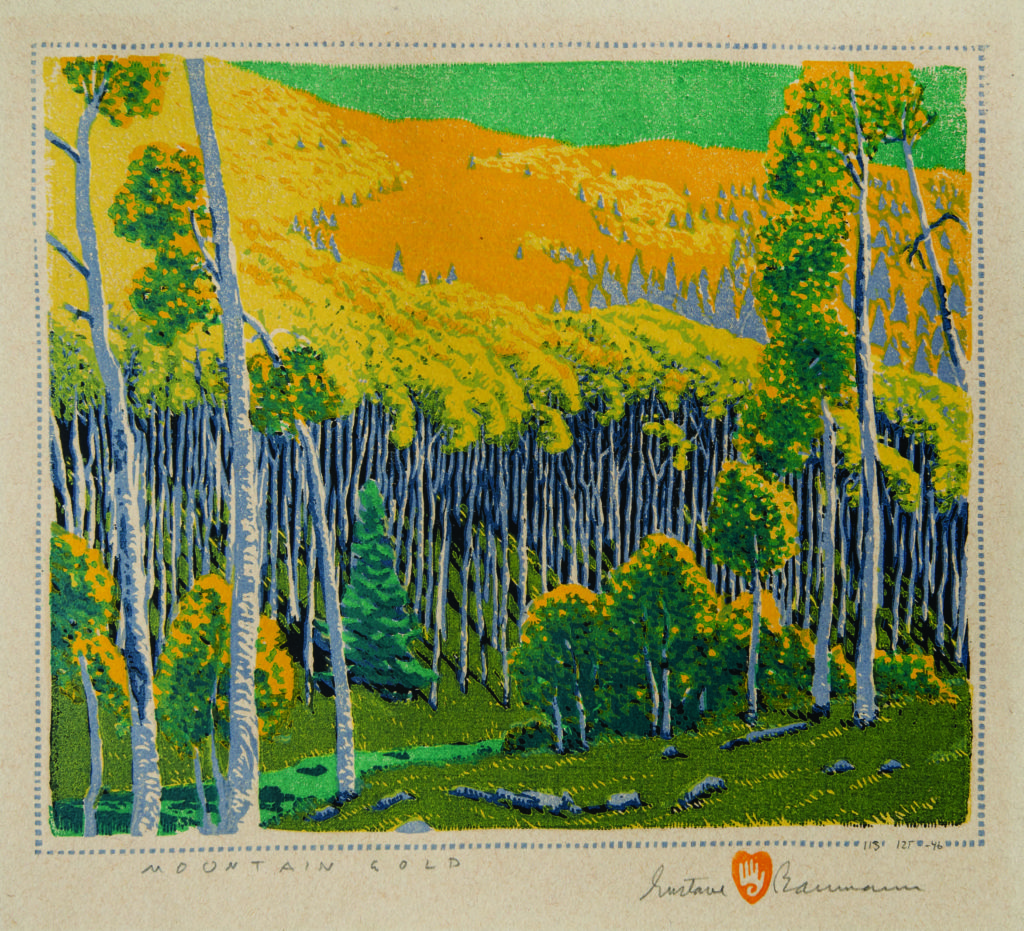

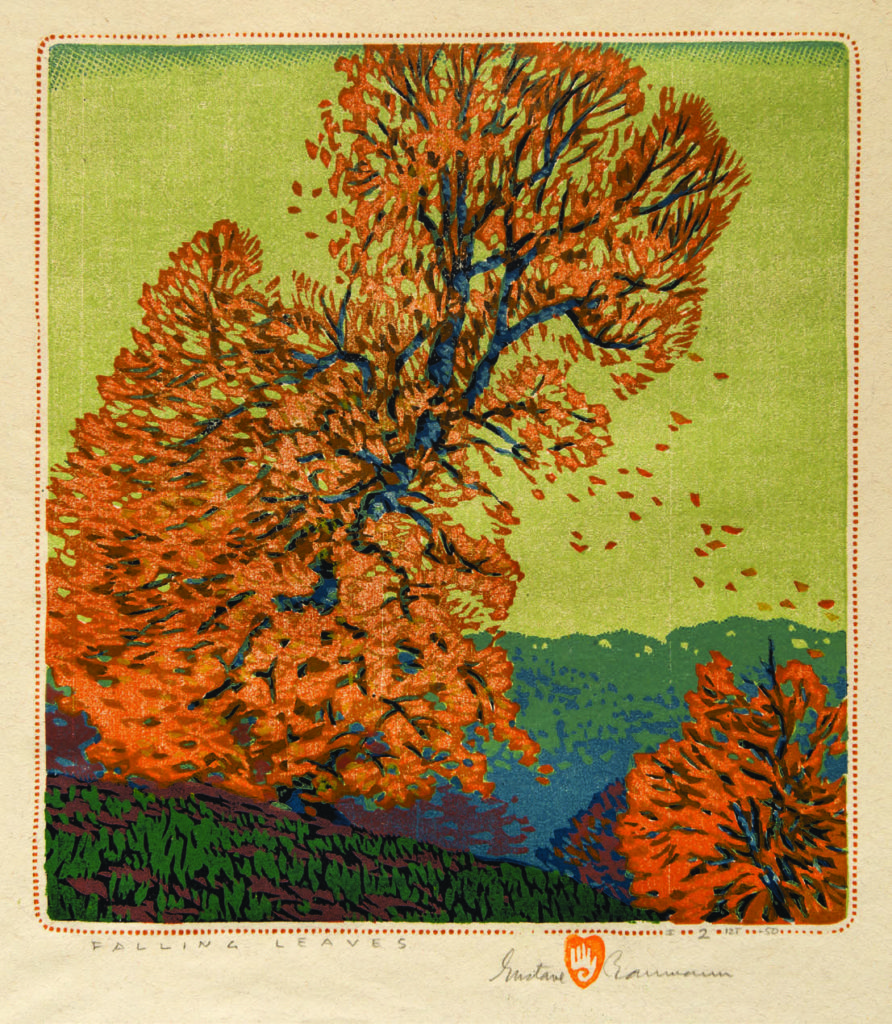

He also built a life in New Mexico. Baumann’s love for the region is clear in his prints. His landscapes—buff-colored adobe houses; orange mesas; rugged mountain ranges; a forest of birch trees ablaze with autumn leaves—lend the territory an almost mythic air of romance. That Baumann’s prints can be found in museum collections in every corner of the United States testifies to their power and popularity.

Fig. 6. Mountain Gold, 1925. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked atlower right, inscribed “MOUNTAIN GOLD” and “113 125-46” under image. Color woodcut, 9 ½ by 11 1/8 inches.

Fig. 7. Autumnal Glory, 1921. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “AUTUMNAL GLORY” and “II 86 125” under image. Color woodcut, 13 inches square.

As much as with his art, Baumann endeared himself to Santa Feans with performance. In 1925 he married Jane Devereux Henderson, a European-trained American actress and opera singer, and two years later they had a daughter, Ann. Initially to entertain their daughter and her friends, the Baumanns began to present elaborate puppet shows. Jane manipulated the strings and gave voice to the characters; Gus built the sets and he carved the marionettes, which eventually encompassed a wide-ranging cast of more than sixty—from Zuni eagle dancers, Percy the Sea Serpent, and a Velázquezian Infanta, to a hapless lady tourist, mischievous elves, and the Baumanns themselves. Audiences packed the living room of their house on Camino de las Animas for the Baumanns’ yearly Christmas show. Since 1993 the performance has been reprised annually during the holiday at the New Mexico Museum of Art using replica marionettes.

Fig. 8. Marionettes made by Baumannin an undated photograph by an unknown photographer. Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe.

Fig. 9. Baumann in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in a photograph by Will Connell (1898–1961), 1932. Inscribed “Gus Baumann, 1932” at bottom. Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, New Mexico History Museum.

Fig. 10. Falling Leaves, 1950. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “FALLING LEAVES” and “1 2 12T 50” under image. Color woodcut, 10 5/8 by 9 5/8 inches.

The originals are among the more than seventeen hundred Baumann objects in the museum’s collection, which include prints, marionettes, and oil paintings (the less taxing medium Baumann turned to in the years before his death in 1971). The Palace Press has produced limited editions of Baumann’s work, including a book, cards, and prints. To celebrate the centenary of his arrival in Santa Fe, the museum will hold a symposium in late September that will feature tours, talks, a documentary screening, and performances. A Baumann catalogue raisonné— more than thirty years in the making—is said to be nearly ready for publication.

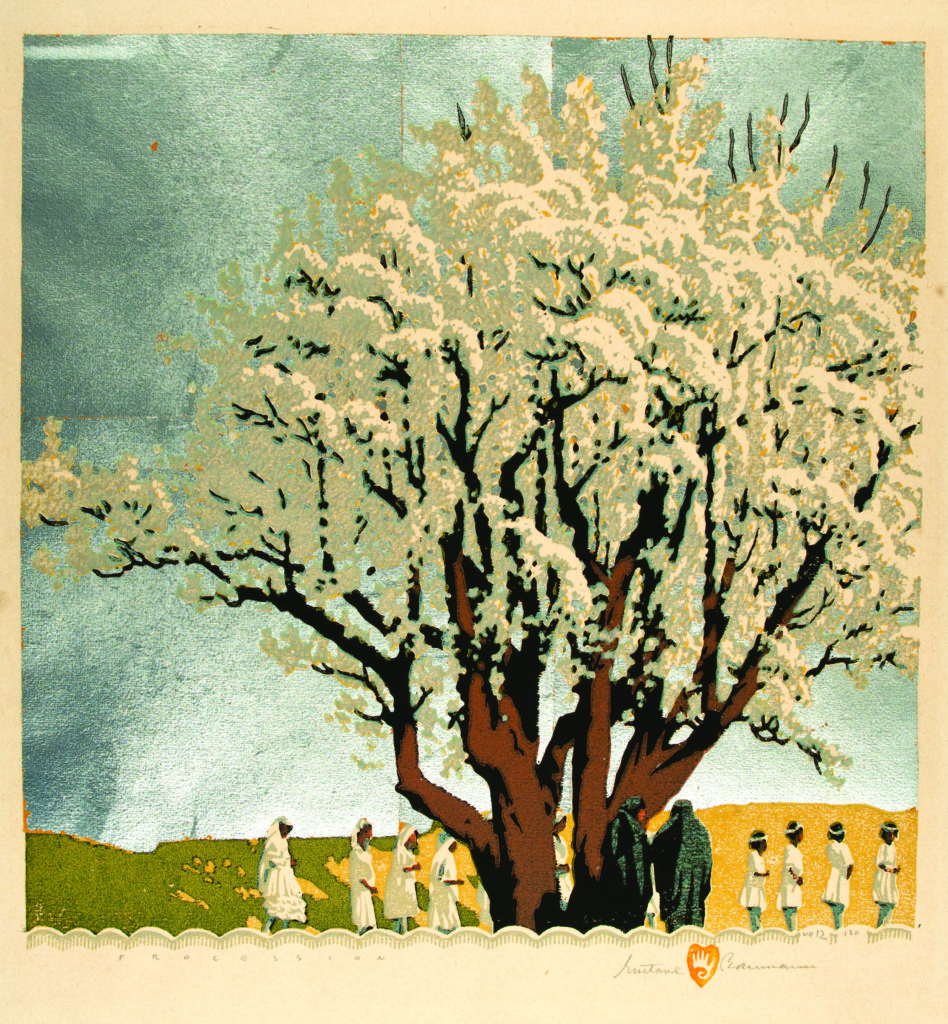

Fig. 11. Procession, 1930. Signed “Gustave Baumann” and watermarked at lower right, inscribed “PROCESSION” and inscribed “NO 12 120” under image. Color woodcut with aluminum leaf, 13 by 12 3/4 inches.

Baumann stamped nearly all his woodblock prints with his watermark: an open hand enclosed within a pomegranate red heart: a universal symbol of welcome and an expression of his belief that art, made by the hand and motivated by the heart, is for everyone. Throughout his life, Baumann refused to sell his beautiful and labor-intensive woodblock prints for more than one hundred dollars. In the twenty-first century, prices for Baumann’s work have, of course, soared. More importantly, they are now also treasured and deservedly celebrated.

SUSAN MORGAN is a Los Angeles-based writer and the editor of Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader (East of Borneo Books, 2012). She was a 2017 fellow at the Women’s Inter.national Study Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.