“Summer Hours,” a new indie French film and critical hit of the season, written and directed by Olivier Assayas, makes antiques into movie stars. The plot hinges on a dozen circa-1900 masterworks, including furniture by Louis Majorelle and Josef Hoffmann, glass and ceramic vases by Félix Bracquemond and Atelier d’Auteuil, and paintings by Camille Corot and Odilon Redon. They belong, in Assayas’s telling, to Hélène Marly, a widow in her late 70s, who inherited them from her famous uncle (and possibly incestuous lover), Paul Berthier, a post-Impressionist painter. (He’s fictional, unlike other artists and artisans mentioned in the movie.) After Hélène’s death, her three widely scattered children—daughter Adrienne is played by Juliette Binoche—regretfully sell off her crumbling stuccoed country house and disperse the collection through sales or donations to the Musée d’Orsay. It may sound arcanely dry, but the gorgeously photographed movie explores French intergenerational conflicts (the grandchildren have entered druggy adolescence, but still mourn the loss of their inherited possessions), secrets that poison lives, and healthy and destructive obsessions with objects.

Here the film’s production designer, François-Renaud Labarthe, explains how the furnishings were selected and assembled, and how they survived a few weeks of shooting in the provinces.

How did you decide exactly which antiques to use on the set?

Olivier did—he wrote them into the original script. Except for the Josef Hoffmann armoire, that was my idea at the last minute, I wanted there to be something completely modern and distinctive to show a completely different side of Paul Berthier’s tastes. The film was originally meant to be a tribute to the Musée d’Orsay, for its 20th anniversary, and Olivier chose most of the pieces from there.

What other collections did you look at?

The Louvre: we copied two of their Corots, which the specialists tell us ours are quite good fakes. We used fake Redons, too, the real ones [at d’Orsay] are too fragile to even exhibit, and would be completely impossible to take outside the museum. The Bracquemond glass is fake, the family refused to loan to us because it was for a film shooting. The Hoffmann came to us from the Galerie Historismus in Paris, and the Atelier d’Auteuil pieces are from Laurens d’Albis, a collector, he was very nice and let us shoot those for free.

Where’s the real house you used as Hélène’s country residence?

It’s about 45 kilometers from Paris, straight north.

How did you get everything up there?

It was all transported by truck at the same time, for a shoot of about 10 days, but the museum pieces had to be brought up separately from the rest. You can’t mix the two, or else it would be a political problem. The museum’s role is to preserve these pieces for posterity, not for commercial or resale purposes.

The curators must have been frantic while everything was on the set.

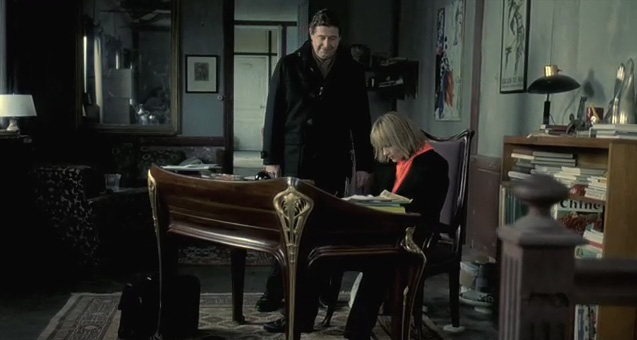

They were very, very nervous. But they checked out everything in advance, to make sure there were no insect or humidity problems in the house. We had security guards there 24 hours a day, and some people from the museum were always near the set to make sure everything was handled properly. Each small prop had to have special rubber on the bottom, so it didn’t scratch or disturb anything underneath. The cast knew how valuable everything was, but they had to behave as if these were normal parts of their daily lives, just regular things.

How did you handle the scenes with the grandchildren running around, were there any special precautions?

We just filmed those scenes outside. You never see the grandchildren interacting with the antiques at all.