Here is the full version, with endnotes, of an article that appeared in a condensed version in our September/October 2018 print edition.

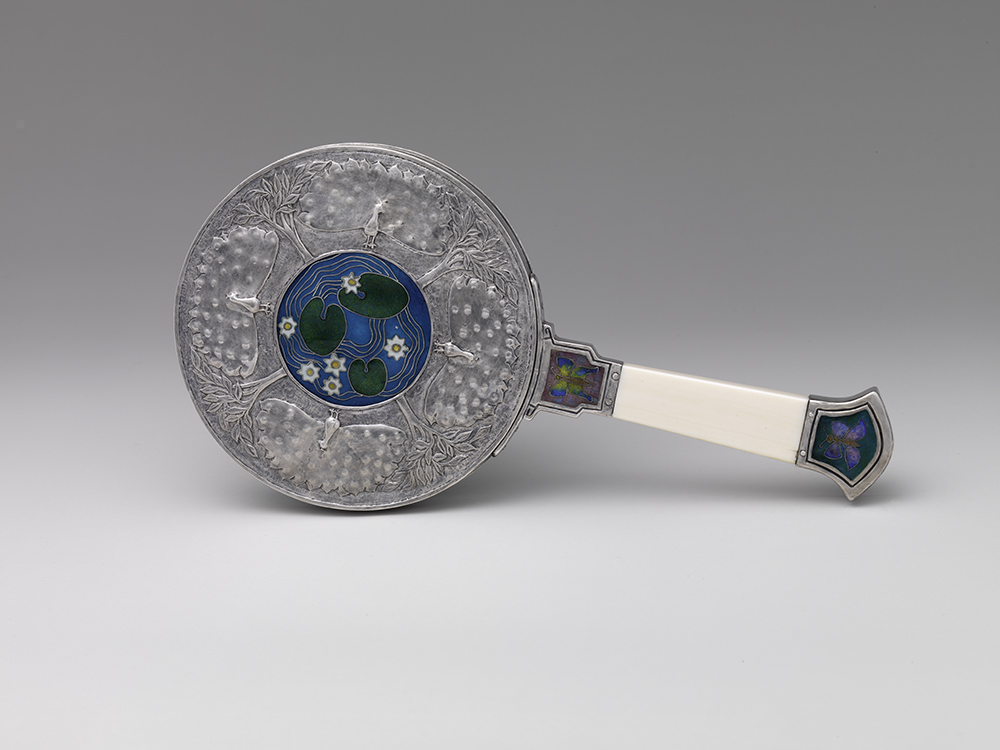

In 2014 the American Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art received a gift from devoted patron Jacqueline Loewe Fowler of a stunning Arts and Crafts silver and enamel hand mirror by Eda Lord Dixon (1876-1926) (Fig. 1). At the time, Eda was virtually unknown, even among Arts and Crafts silver scholars, principally because she rarely signed her work. Fortunately, the hand mirror had been published and credited to her in the journal Palette and Bench.1 The gift prompted staff of the American Wing to embark on research into Eda’s life and work, resulting in the rediscovery of an influential, award-winning American silversmith, enamelist, and jeweler of the early twentieth century. As a consequence of The Metropolitan Museum’s project, Eda’s sketch, design, and account books were discovered, and thanks to her descendants they are available through Watson Library’s digital collections portal. With these resources, collectors and scholars now will be able to identify and document more of Eda’s work.2

Fig. 1. Hand mirror [back], c. 1908. Silver, ivory, enamel, and glass; length 9 5/8, diameter 4 5/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

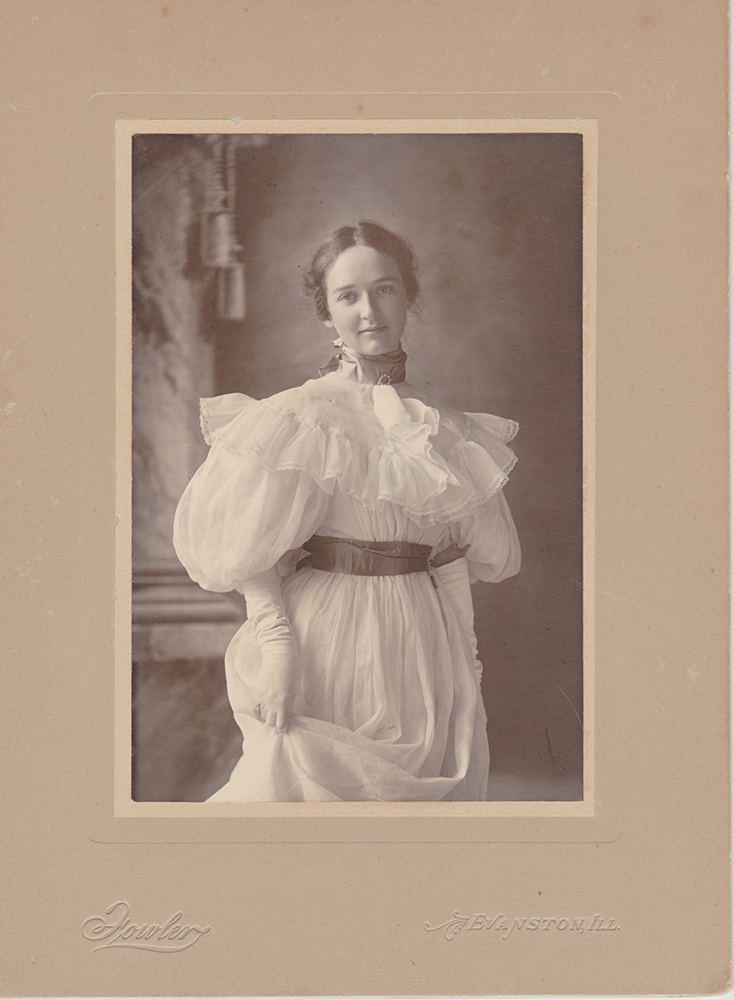

Eda Lord Dixon grew up in an artistic and progressive milieu in Evanston, Illinois. Born in Evanston on November 30, 1876 to George Sterling Lord (1850–1916) and Eda Isadore Hurd Lord (1854-1938), she was the second eldest of nine children.3 Eda’s father was a partner in his father’s Chicago wholesale drug firm, Lord, Stoutenburgh & Co.4 Her mother was a pianist and artist.5 One of the earliest public accounts about Eda, a newspaper report of her marriage on Christmas Eve in 1896, describes her as a pretty and vivacious young lady who married William S. Young (1873–1964), a member of her social set in Evanston and a commission merchant at the Board of Trade in Chicago (Fig. 2).6

Although little is known of Eda’s schooling, she likely began her education in silver and enamel work in 1903. She studied with James Herbert Winn (1866–1940), an influential jeweler and instructor, who began teaching at the Art Craft Institute in Chicago in 1903. Founded in 1900 by T. Vernette Morse, the Institute offered practical training in the evenings and weekends to women and men seeking a career in the arts and crafts.7 At this time, Eda was known professionally as Mrs. William S. Young or Eda Lord Young. Widely promoted as an appropriate field for women, especially for those who had to earn a living, artistic jewelry required a relatively small space and could be executed at home or in a modest-sized workshop with inexpensive tools. The sizeable demand for articles of adornment ensured steady income.8

Fig. 2. Eda Lord [Dixon] in a photograph by Edward L. Fowler (1862–1940), c. 1896. Collection of Shelly and James Dixon.

Eda’s early work reflected her teacher’s influence. Winn’s style and choice of materials embodied the Chicago Arts and Crafts aesthetic, and his oeuvre consisted of hammered and/or pierced silver, gold, and copper jewelry with conventionalized geometric and foliate ornament often set with semiprecious gemstones, such as coral, lapis lazuli, opal, pearl and chalcedony.9 From 1904 through 1905 Eda showed and sold her work, principally jewelry, at exhibitions, including ones at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Detroit Museum of Art (now Detroit Institute of Arts).10 Surviving records show her wares included a variety of jewelry forms as well as small objects such as handbags and spoons. In addition to floral and geometric motifs, Eda’s early work demonstrated a diverse decorative vocabulary and styles. Some motifs she favored were peacock feathers, leaves, thistles, Celtic entrelacs, and trees.11 While Eda worked primarily in silver, she also employed copper and gold. Like Winn, she preferred semi-precious gemstones, a hallmark of Arts and Crafts jewelry, in which the artistry of juxtaposing colors and finely crafted metalwork was emphasized over the use of more valuable precious stones and ostentatious settings. Eda’s early jewelry and metalwork were hammered. In addition, she embellished her work by cutting out areas of the metal to form designs, as well as engraving, and enameling, usually in blue or green, but sometimes violet, white, and black.

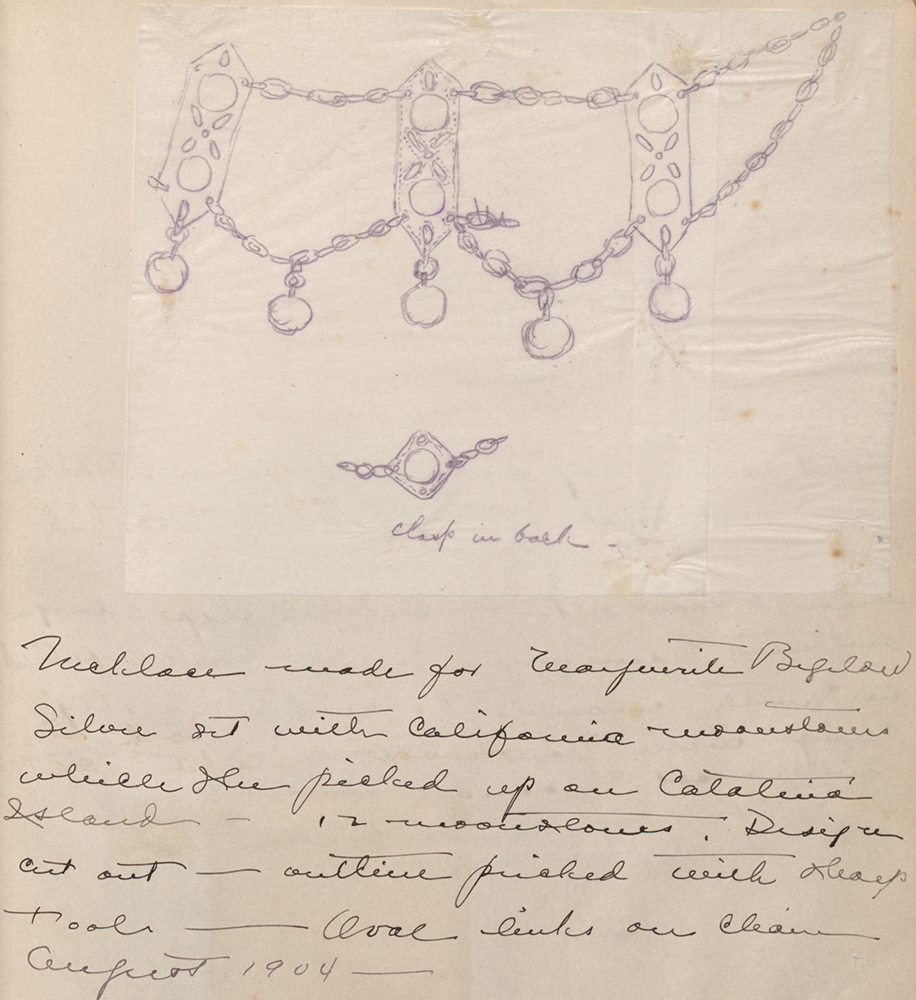

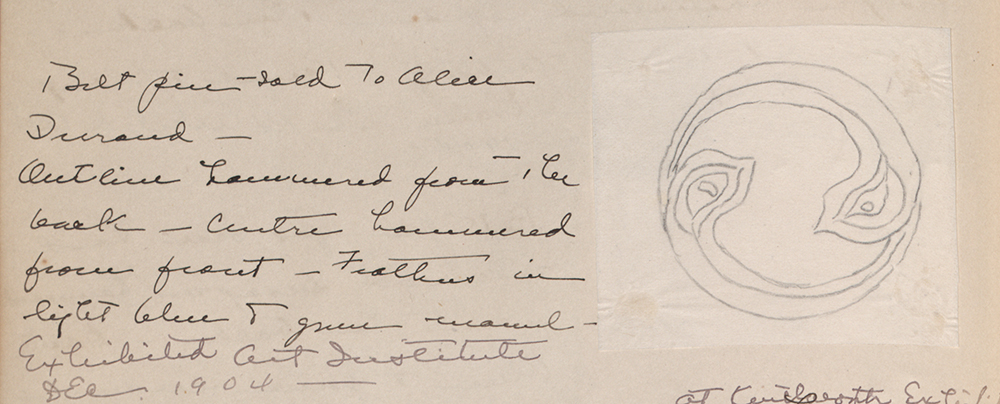

One example of her early jewelry, designed in August 1904 for Marguerite Bigelow, is a silver necklace set with California moonstones gathered by Bigelow on Catalina Island (Fig. 3).12 Another is a round belt pin sold to her friend Alice Durand depicting two entwined light blue and green enamel peacock feathers in the Art Nouveau style, exhibited at the Art Institute in December 1904 (Fig 4).13 During the first years of her career, most of Eda’s customers appear to have been friends and family.

Fig. 3. Sketch and description of necklace made for Marguerite Bigelow, August 1904, in Sketch and ledger book, 1904–1905, p. 13. Graphite, ink and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In June of 1905, Eda left her husband and family in Evanston and moved to London to pursue her education in metalwork and enameling.14 Her desire to leave home was likely precipitated not only by a passion for her work but also by an unhappy marriage and, possibly, the embarrassment that resulted from the bankruptcy of her father’s business.15 In England she studied with Alexander Fisher (1864-1936), the most important and influential British enamelist of the day.16 While teaching in art schools, he maintained a studio and school for private students in Kensington.17

Fig. 4. Sketch and description of belt pin sold to Alice Durand, c. December 1904, in Sketch and ledger book, 1904–1905, p. 6. Graphite, ink and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

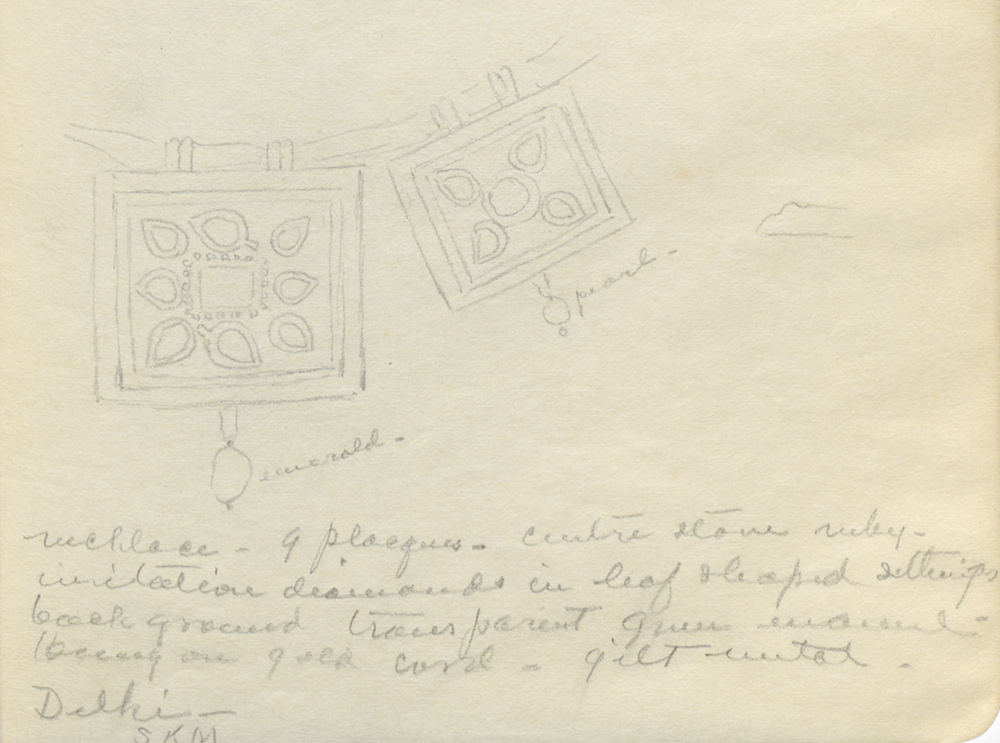

Eda spent three years in London during which time she filled several notebooks with graphite and watercolor sketches of objects she saw at the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria & Albert, (designated “SKM” in her sketches), and the British Museum (“BM” in her notes).18 The sketches she made of objects from diverse cultures, places, and moments in time remained a source of inspiration throughout her career (Figs. 5, 6). In London, and perhaps later in Evanston, Eda realized several of the designs in her notebooks, some of which indicated they were drawn by Mr. Fisher. One such design she executed—identified as provided by Fisher—was a silver and cloisonné enamel belt buckle in a floral motif (Fig. 7).19

Fig. 5. Sketch and description of a necklace made in Delhi at the South Kensington Museum, c. 1906, in Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 36. Graphite and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

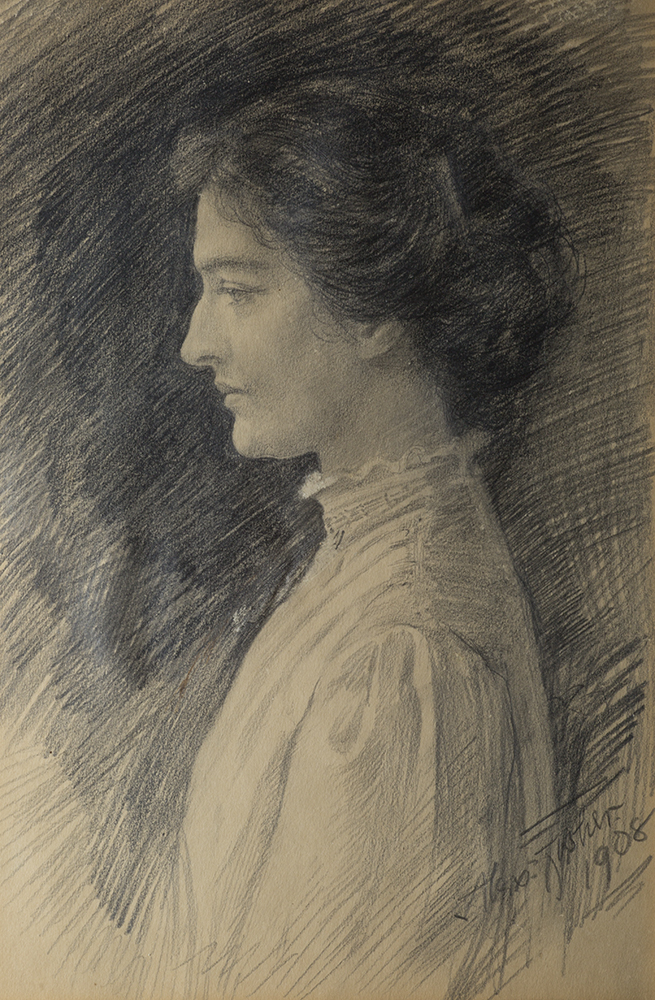

Eda continued to show her work in American exhibitions while she was in London.20 In October of 1906 she became a member of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit,21 and records indicate she sold one of her works through the Society in December of that year.22 During the spring and fall of 1907, Eda exhibited at two of the Society’s shows featuring metalwork, enameling, and jewelry, the latter including English and American objects. Fisher appears to have been the contact through which the Society accessed European works.23 Before her departure from England on September 19, 1908, Alexander Fisher sketched a portrait of Eda portraying her as a Pre-Raphaelite beauty (Fig. 8).24

Fig. 6. Neck ornament, maker unknown, Delhi, India, date unknown. Glass, gold thread, pearls, and enamel. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Eda’s husband, William S. Young, visited her in London during the fall of 1906. His visit appears to have confirmed their incompatibility; by 1907, they no longer listed their official residences at the same address, instead using their respective parents’ domiciles. In the summer of 1907 Eda had a visitor from Chicago, Laurence Belmont Dixon (1870–1953), an electrical engineer, who would become her second husband and partner in craft after she returned to Evanston. As Laurence was a founding member of Chicago’s Morris Society, a group interested in modern artistic and social trends, it is not surprising that in Laurence Eda found a compatible spouse.25

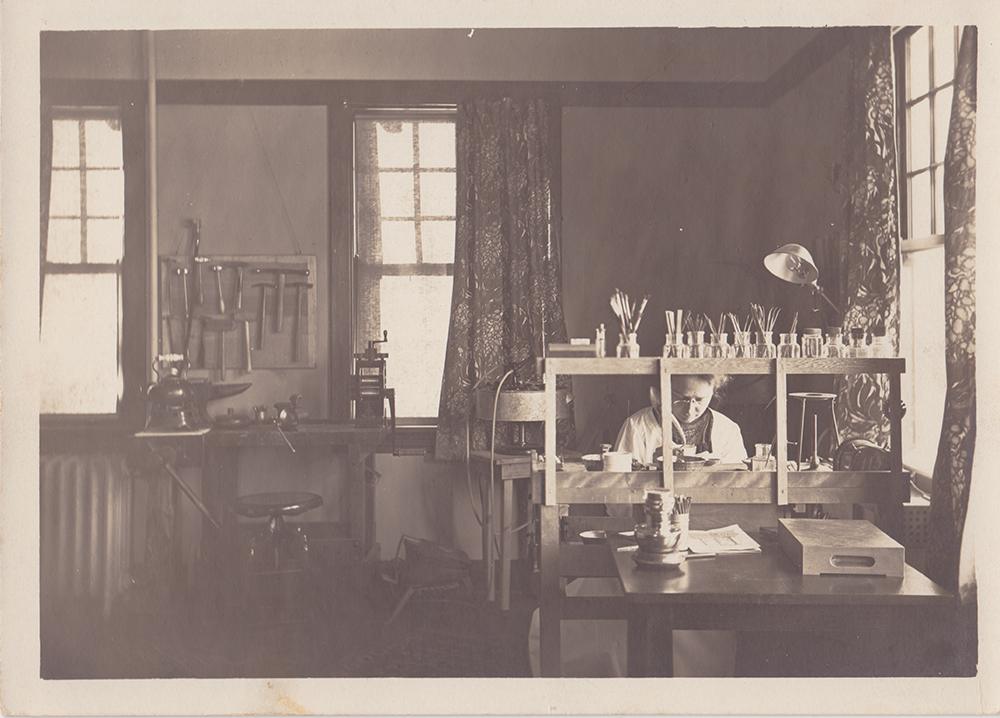

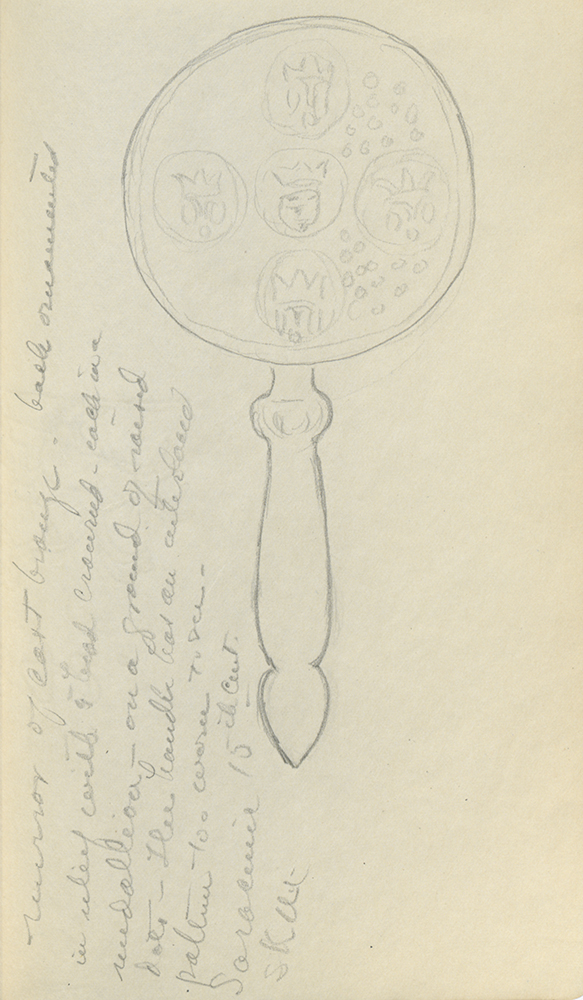

Upon her return to Evanston in 1908, Eda set up a studio (Fig. 9). The aesthetic and technical lessons learned during her studies and practice with Alexander Fisher were manifest at the Seventh Annual Exhibition of Original Designs for Decorations and Examples of Art Crafts having Distinct Artistic Merit at the Art Institute of Chicago, December 8–22, 1908.26 Here, The Metropolitan Museum’s hand mirror was exhibited for the first time (Figs. 1, 10). Eda’s sketches of a “Saracenic” round hand mirror with handle at the South Kensington Museum suggest her source (Fig. 11). Her notes described it as a “mirror of cast bronze. back ornamented / in relief with 5 head crowned – each in a / medallion— on a ground of raised / dots —This handle has an interlaced / pattern too worn to see – / Saracenic 15th cent. / SKM.”27 In the same sketchbook she made drawings of other metal hand mirrors as well as details of Etruscan, Mankratis, and “Saracenic” mirrors in the South Kensington Museum and British Museum collections.28

Fig. 7. Sketch of belt buckle, c. 1906, in Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 14. Graphite, watercolor, and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Eda inventively translated the bronze “Saracenic” design into silver, enamel, and ivory. On the back of the mirror, she substituted a cloisonné enamel circular reserve of sinuous green lily pads and yellow-eyed white flowers on a turquoise ground for the central medallion of a crowned head, and a surround of four peacocks with plumage displayed alternating with leafy trees for the four medallions of crowned heads. In the “Saracenic” mirror sketch, the crowned heads are on a ground of raised dots; in Eda’s mirror, she has punctuated the plumage of the stylized silver peacocks with raised dots to suggest the eyes of their feathers.29 Inspired by a fifteenth-century cast bronze Middle Eastern hand mirror with royal figural decoration, she created a masterpiece of Arts and Crafts handwork.

The following year, Eda exhibited the hand mirror again with three other silver and enamel pieces of hollowware at the Architectural Exhibition of the Detroit Architectural Club and the Society of Arts and Crafts. In addition to the hand mirror, she showed a silver and enamel box, a silver and enamel finger bowl, and a silver and plique-a-jour enamel bowl.30 In the same year, 1909, Eda made an engagement ring and a seed-pearl and enamel necklace for her brother Tom Lord (1880–1951) to give to his bride, Helen Dewar (1886–1947).31 This necklace, still owned by a descendant of the family, consists of four parallel strands of seed pearls connecting a central lozenge-shaped plaque with eleven smaller flanking plaques (Figs. 12, 13).32 Inspiration for the necklace appears in Eda’s London Sketchbook, dated February 1906, where she drew a detail of a gilt metal necklace from Delhi at the South Kensington Museum consisting of nine square decorated plaques hung on a gold cord (Figs. 5, 6).33 Throughout much of her career, Eda continued to make necklaces and bracelets of multiple strands of seed pearls.

Fig. 8. Portrait of Eda Lord [Dixon] by Alexander Fisher (1864–1936), c. 1908. Graphite on paper, 13 1/8 by 8 2/3 inches. Collection of Shelly and James Dixon, © Chuck Place Photography.

On July 26, 1909, Eda married Laurence Belmont Dixon, generally known as “L.B.,” the son of Ella Belmont Smith and Laban Beecher Dixon,34 a well-known Chicago architect.35 After graduating from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Laurence spent fifteen years working for Western Electric, the manufacturing subsidiary of American Telephone and Telegraph Co. Immediately after the wedding, the Dixons moved to Riverside, California where they built a seven room house, designed by the Prairie School architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Gray, on a ten-acre orange grove at the corner of Victoria Avenue and Madison Street.36 While raising two sons, Robert Lord Dixon, born in 1911, and Richard Belmont Dixon, born in 1912, maintaining an orange grove, and actively participating in the Riverside community, the Dixons worked together designing and making hollowware and jewelry. Laurence’s collaboration with Eda expanded the scale and scope of her enterprise. No longer making a limited number of pieces for mainly family and friends, Eda and Laurence, instead, retailed their work through exhibitions and Arts and Crafts societies. Their son Richard described the Dixons’ working process: “The silver and gold pieces Mother and Dad made were of a very fine quality. Dad, being by nature, a craftsman and a perfectionist, helped with many of the projects. Some articles were made to order and others were sold on consignment through the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston.”37

Richard also provided an evocative description of Eda:

Mother was endowed with a delightful personality, and made friends easily. She had whatever it takes, energy, initiative, ambition, thoughtfulness to keep in touch with many friends of her youth. Thus she was a great letter writer…. Mother wore pince nez glasses that were as much a part of her as the way she did her hair up in a bun in back. Dad had a Van Dyke beard and mustache….. Mother smoked cigarettes… at a time when smoking by women was not universally accepted….Mother often used a cigarette holder and at one stage of her creative career she made cigarette holders. She bought ivory holders and fashioned an enameled silver band that was affixed to the holder near the tip. Very elegant.38

From the beginning of their partnership, the Dixons enjoyed success. In 1910 they were named Craftsman members in the field of jewelry by the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston.39 From then on they produced numerous designs, exhibited, and sold pieces through the exhibitions and the shops at the Arts and Crafts Societies in Detroit, Chicago, and Boston. In the fall of 1910 the Detroit Arts and Crafts Society hosted a solo show at which the Dixons exhibited for sale “over fifty pieces of jewelry, enamel and silver, beautiful in design and workmanship and with a remarkable range in technique.”40

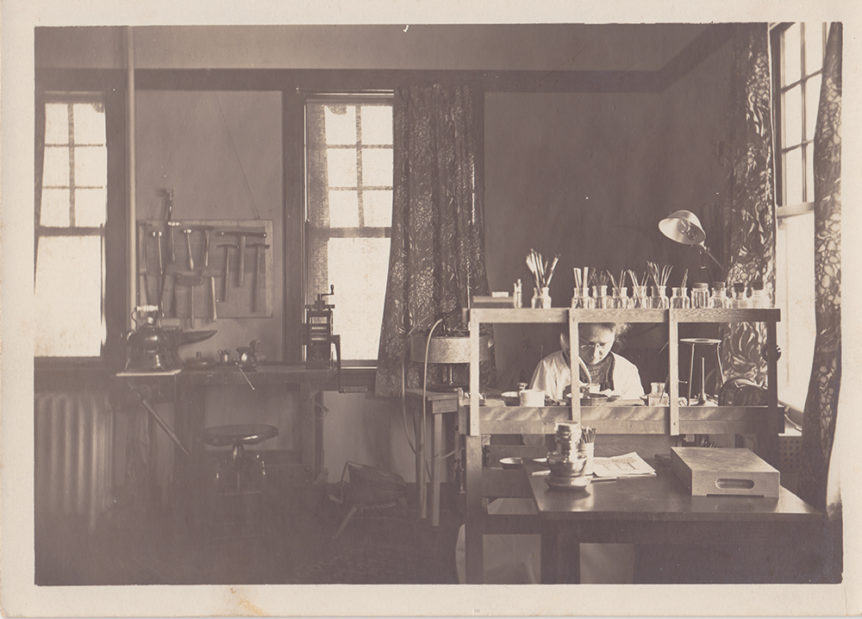

Fig. 9. Eda Lord Dixon in her studio in Evanston, Illinois, in a photograph of c. 1908. Collection of Shelly and James Dixon.

They also showed fourteen objects at the Ninth Annual Exhibition of Original Designs for Decorations and Examples of Art Crafts having Distinct Artistic Merit, held at the Art Institute of Chicago in December of that year, including two finger bowls. Eda began to make finger bowls in 1909; two, owned by Dixon descendants, were used at family Thanksgivings.41 The surviving examples indicate that Eda’s finger bowls were simple, Colonial Revival style silver bowls ornamented on the interior bottom with a circular cloisonné enamel image of animals or flowers. One of the extant bowls depicts birds perched on a flowering tree and the other a Japanese style blue and white swimming carp (Fig. 14), similar to a corresponding sketch marked “#4” in the Green Design Album. From the time Admiral Perry opened trade between Japan and the West in 1853, European and American fine and decorative arts had embraced Japanese influences; however, the Dixons’ interest in Japanese design also may have stemmed from Laurence’s trip to Japan with his father in 1905. The visit so fascinated him that he took over 175 photographs.42

Fig. 10. Hand mirror [front], c. 1908. Silver, ivory, enamel, and glass; length 9 5/8, diameter 4 5/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Their first decade in California was a busy and productive time for the Dixons, and period discussions of their work make clear that they had become well-known and respected artisans. Their accomplishments were on display at a sale presented by the Society of Arts and Crafts in Detroit, April 3–30, 1912. According to the sale’s announcement, “Prominent among the exhibitors are: Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence [sic] Belmont Dixon, jewelers and silver and goldsmiths, whose work needs no further introduction to this public. They have sent opera and calling bags of rich oriental fabrics, mounted in cloisonné enamels; sets of sleeve links and scarf pins, in which some fine California moonstones, jade, etc., are used; also silver and enamel boxes, brooches, etc.”43 Again in November the Society mounted a special exhibition of jewelry by Mr. and Mrs. L.B. Dixon in conjunction with a collection of silver by Arthur Stone, James T. Wooley, and George P. Blanchard.44 The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston recognized the Dixons’ artistic accomplishments by promoting them from Craftsman to Master level membership in 1912.45 The Council of the Society conferred the title “Master” on those members who had “clearly established a standard of excellence.”46

The Dixons continued to exhibit in group shows and special exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit over the ensuing decade. In 1913, the Jury of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston commended their work.47 One of their necklaces was featured in House Beautiful in 1915 and described as follows: “a green and gold necklace of malachite, in enameled setting of corresponding green and with small pearls to vary the gold of the chain—that are equally striking for workmanship and intrinsic beauty.”48 A photograph of this necklace appears in one of Eda’s photograph albums.49

Fig. 11. A page from Dixon’s Sketchbook: London, June 1906, detailing a fifteenth-century “Saracenic” hand mirror from the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum, c. 1906. Graphite on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Eda again exhibited the hand mirror now in the Metropolitan’s collection (Figs. 1, 10), in an exhibition of craftspeople of Southern California located in the Southern California Counties Building of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition at San Diego. On this occasion, the mirror was illustrated in House Beautiful.50 The Exposition, held January 1, 1915–January 1, 1917 in Balboa Park, celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal and San Diego’s role as the first port of call for ships sailing north after passing west through the canal. The hand mirror was clearly a work of which Eda was particularly proud, as throughout her career she chose it to represent her artistic vision and skill.

Nineteen sixteen proved to be a banner year for the Dixons. The hand mirror was illustrated yet again, this time in Hazel H. Adler’s book, The New Interior: Modern Decorations for the Modern Home (1916).51 In February, 1916 the Dixons were given a bronze medal, one of the prizes awarded each year at the annual meeting of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, for excellence of work.52 Their prize was for jewelry; the other two medalists were Elizabeth Copeland, for enamel work on silver, and James Woolley, for silver. The same year, Laurence, a professional member of the Chicago Artists Guild, received the Guild’s Prize, the top prize of four awarded for jewelry in the Arts and Crafts exhibition on view May 1 to May 13, 1916.53 James H. Winn, Eda’s former teacher, was the Vice-President of the Guild and Chairman of the Committee for the selection of Arts and Crafts. The Artists Guild provided a venue for artists and craftspeople, including the Dixons, to sell their wares.54 As they often did, the Dixons also exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual exhibition of Applied Art and Original Designs for Decorations (October 12–November 15, 1916), where their focus was entirely on gold jewelry ornamented with enamel and gemstones.55

Fig. 12. Necklace made by Dixon for Helen Dewar Lord (1886–1947), c. 1909. Gold, pearls, sapphires, and enamel; length 15, height 1 3/4 inches. Collection of Suzanne F. McCullagh.

The following year, the Dixons again exhibited gold jewelry at the Art Institute of Chicago Applied Arts show and held a special exhibition of their gold and silver jewelry at the Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit. In the announcement for the Detroit show, the Society gushed:

This is, by far, one of the most important exhibitions of the arts of goldsmithing and enameling ever seen in Detroit. Mrs. Dixon was during several years a pupil of Alexander Fisher of London, England, and every piece bears testimony to the perfect technique of his training, coupled with the artist’s sense of the relation of gems to settings. Detroit is indeed fortunate in securing work so much in demand.”56

At the Art Institute of Chicago’s Applied Arts exhibition in October 1919 the Dixons showed three objects—two rings and a pair of earrings—all in platinum, their earliest use of this material. The pair of platinum and sapphire earrings are the first earrings Eda is known to have exhibited.57 Although no images from the display survive, Eda’s Green Design Album gives us a sense of their appearance.58

Fig. 13. Sketch of filigree necklace, n.d. [top] and sketch of necklace made for Helen Dewar Lord [bottom], c. 1909, in Red Design Album, p. 23. Graphite, watercolor, and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the end of the decade, the Dixons’ participation in exhibitions decreased considerably. Yet, in October 1920, the Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit lauded a work by the Dixons that had been shown in the spring and then again recently by the Society: “[a]n oval box of silver, the cover set with enamel medallion, considered by these craftsmen their finest bit of work, has unique handles of silver-set chrystal [sic]” (Fig. 15).59 That same month, on October 15, George G. Booth (1864–1949), an art collector, philanthropist, and founder of the Cranbrook Educational Community, purchased Eda’s hand mirror from the Society for $120. Shortly thereafter, on December 29, 1920, he also bought from the Society the oval silver and enamel jewel box by Eda and Laurence for $140. Booth donated the hand mirror and the jewel box to the Detroit Institute of Art on December 21, 1920.60

Fig. 14. Finger bowl with swimming carp enamel plaque, n.d. Silver and enamel; height 2, diameter 4 ¾ inches, enamel plaque diameter 2 1/8 inches. Collection of Shelly and James Dixon, © Chuck Place Photography.

The oval box and the hand mirror shared the same provenance for the next fifty-two years. They were lent by the Detroit Institute of Arts along with several other silver objects from the Booth Collection, to the Tricennial Exhibition of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, March 1–March 20, 1927.61 Immediately thereafter, the jewelry and silver from the Tricennial Exhibition were shown at the Boston Arts and Crafts Society’s newly opened New York gallery, located at 721 Madison Avenue.62 In December 1944, the Detroit Institute of Arts returned the hand mirror and the box, among a number of other objects, to George G. Booth in exchange for a sculpture in the Booth collection, whereupon they were accessioned by the Cranbrook Art Museum.63 Eda’s hand mirror and box remained at Cranbrook until 1972.64 The hand mirror was next offered for sale at Sotheby’s in 2013, when it was bought by Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, who donated it to The Metropolitan Museum in 2014.65 The purchaser of the jewel box at the 1972 sale sold it at Sotheby’s in 2016.66

Fig. 15. Covered box by Eda and Laurence Dixon, n.d. Silver, enamel, and crystal; height 3 3/8, width 6 ¼, depth 2 7/8 inches. Collection of Richard H. Driehaus; photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2016.

The Dixons’ creative engagement with silver and enamel extended to a diverse range of objects, including handbag frames. Even before Eda went to London to study with Fisher, she created a silver and enamel frame in a conventionalized floral motif, a design inspired by the tapestry fabric portion of the bag.67 Later in her career Eda made some of the textiles for the handbags herself. According to her son Richard, “There were knitted bead bags each with a pair of enameled silver tops and a silver chain. These bags must have sold like the proverbial hotcakes because she was knitting at them furiously and became able to turn out the knitted portion in short order.”68 A watercolor design by Laurence shows a stencil-like enamel floral design on a curved silver handbag frame (Fig. 16).69 A descendant of the Dixons owns a hand-knitted handbag with a silver and enamel floral frame in a similar style (Fig. 17).70 This type of decoration appears on some of the Dixons’ hollowware, including the oval box with the same provenance as the hand mirror (Fig. 15).

Fig. 16. Sketch of handbag frame by Laurence B. Dixon, after 1909, in Green Design Album, p. 92. Graphite and watercolor and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Although Eda produced far more jewelry than silver ware, most of her surviving known oeuvre is hollowware; a silver chalice, or communion cup, is still in the family as are several boxes (Fig. 18).71 The chalice, first shown at and praised by the Society of Decorative Arts, Detroit in 1920, and again at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1921,72 was in a traveling exhibition of American handicrafts organized by the American Federation of Arts in 1922–1923 with seven museum venues including The Metropolitan Museum of Art.73 According to the Dixons’ son Richard, Laurence hammered out the bowl and base of the chalice, and then Eda pierced the juncture between the two and did all the engraving.74 Richard writes:

There is a silver chalice 6 1/4 inches tall and 4 3/4 in. in diameter with the words “The magic words of life are here and now” engraved around the rim. This cup and its base are hammered silver and there is a carved design around the rim of the base. In the center where the bowl and base join is a pierced silver ornamentation that originally had enamel work in the design, but this had gradually chipped out, so Mother removed all the enamel leaving the carved out design which in itself is very pleasing.75

The engraved phrase on the chalice is from the Rubàiyàt of Omar Khayyam.

Fig. 17. Handbag by Dixon, date unknown. Silver, enamel, glass beads, and thread, 10 ¼ by 8 inches. Collection of Mary Dixon Howard.

Another family heirloom is a small cartouche-shaped box ornamented in a simple blue and green champlevé stylized leaf and flower design in which Eda stored her postage stamps.76 The family also owns an elaborate kidney-shaped box embellished with blue and green champlevé floral motifs, its lid ornamented with a plaque of carved white jade (Fig. 19). It was exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1921.77 Richard Dixon described his parents’ process in making the box: “It was designed to conform in shape to the jade carving on the lid. The box was made by my father and my mother did the engraving and enameling.… It probably took three applications of enamel, each filling fired in the old fashioned furnace of the time. To complete the job the final polishing was done by hand, then fired again.”78 The decoration of and materials in this box, created by the Dixons about 1920, reflect Chinese inspiration, an interest evident in Eda’s early sketches.79

Fig. 18. Chalice by Eda Lord Dixon and Laurence B. Dixon, c. 1922. Silver, 6 by 4 5/8 inches. Collection of Mary Dixon Howard.

The Dixons’ most impressive extant work is a rectangular silver box signed and dated “E & L DIXON / 1924” that was recently made a promised gift to The Metropolitan Museum (Fig. 20). It is to date the only known example of work signed by Eda or the Dixons together. The engraved flowers and leaves and the floral cloisonné enamel plaques are similar to other work by the Dixons in the Chinese style; however, the engraved and pierced silver portions of the lid within arabesque surrounds, each set with colored gems, also convey other exoticized non-Western aesthetic sensibilities. The design of the box successfully combines an interplay of solids and voids, as well as of rectilinear and curved forms, resulting in a striking work of art that embodies the best of the Dixons’ jewelry and metalwork.

Fig. 19. Box by Eda and Laurence B. Dixon (1870–1953), c. 1920. Silver, jade, ivory, and enamel; height 1 ¾, width 3 ¾, depth 2 ¼ inches. Collection of Shelly and James Dixon, © Chuck Place Photography.

Along the edge of the top of the box an engraved message reads: “AND AT THE RAINBOWS FOOT LAY SURELY GOLD.” The reference to gold and the use of the jewel-hued stones suggest that this box may have been intended as a jewel box. The engraved phrase on the lid is a line from “Aloof,” the first of a group of three sonnets by Christina Rossetti (1830–1894), a well-known poet and the sister of the Pre-Raphaelite poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Fig. 20. Box by Eda and Laurence Dixon, 1924. Signed and dated “E & L DIXON/ 1924” on base; inscribed “AND AT THE RAINBOWS FOOT LAY SURELY GOLD” on the lid. Silver, enamel, garnet, rose quartz, rubellite, sapphire, peridot, chalcedony, and shell; height 2 ¼, width 5 1/8, depth 3 ½ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, promised gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The box’s use of undulating solids and voids is a major theme in the Dixons’ jewelry designs throughout the second decade of the twentieth century. Eda’s design albums provide numerous examples in this filigree style (Fig. 13, upper sketch).80 A filigree gold and pearl bracelet remains in the Dixon family (Fig. 21).81 Eda was first exposed to filigree jewelry in London at the South Kensington Museum. She sketched a detail of a nineteenth-century silver filigree necklace of eleven rosettes connected by chains made in Cuttack, India.82 After Eda returned from London, and especially after she and Laurence moved to Riverside, California, her jewelry designs became increasingly more delicate and complex. The Dixons ceased exhibiting their work in 1923, and in 1925 they sold their house in Riverside, and moved to their vacation cottage in Del Mar, California.83 Eda died on February 14, 1926 of an acute infection of the liver and gall bladder.84 Posthumously, in January 1927, gold and silver jewelry by the Dixons was included in an exhibition of Arts and Crafts work by local artists at the library of the junior college in Riverside. Laurence did not continue working professionally in silver and enamel after Eda’s death, but he remained close to her family, some of whom had moved nearby in California.85

Fig. 21. Bracelet, n.d. Gold, rubies, and pearls; height ¾, width 7 ¾, depth 3/16 inches. Collection of Mary Dixon Howard.

Eda Lord Dixon drew on her training in enamel work under Alexander Fisher and her study of international historic decorative objects in museum collections in London to become an important creative force in the American Arts and Crafts movement. Her work, much of which she produced in collaboration with her husband Laurence, reveals masterful craftsmanship and imaginative vision. As scholars and collectors have an opportunity to study her sketchbooks, photograph albums, and design books, more of the Dixons’ work will come to light and contribute to our understanding of their fascinating and impactful lives and careers.

MEDILL HIGGINS HARVEY is Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts and manager of the Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

LORI ZABAR is an independent decorative arts historian and curator and a former research associate in the American Wing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1 “Art Institute Exhibition,” Palette and Bench 1 (March 1909), 143. 2 There are nine scanned books by Eda Lord Dixon accessible through the Thomas J. Watson Library portal, courtesy of Shelly and James Dixon, Santa Barbara, CA at http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/. Sketch and ledger book (including loose sketches), 1904–1905; Sketchbook: London, February 1906; Sketchbook: London, June 1906; Small Sketchbook: London; Small Sketchbook II: London, February 1906; Photograph Album 1; Photograph Album 2; Red Design Album; Green Design Album. We would like to thank the Dixon family for their generous support of our research. Without their contributions this article would not have been possible. 3 1880 US Federal Census, Ancestry.com. 4 “In the Cities,” Western Druggist, 25 (April 1903), 221. 5 Sally Brown Moody, “Magnificent Music Collection Presented to Library at La Jolla as Memorial to Mrs. Eda Hurd Lord,” San Diego Union (June 25, 1939), 32. 6 Cook County Illinois Marriages Index, 18701-–1920, Ancestry.com; Clipping, Young-Lord wedding announcement, Evanston News-Index (December 26, 1896), courtesy of Evanston History Center, IL. 7 Darcy L. Evon, Hand-Wrought Arts & Crafts Metalwork & Jewelry 1890–1940 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2013), 9–10, 45. 8 Sharon S. Darling, “Beautiful, Useful and Enduring: Chicago Arts and Crafts Jewelry,” in Elyse Zorn Karlin, ed., Maker & Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2015), 192. 9 Evon, Hand-Wrought Arts & Crafts Metalwork, 45–47. See http://chicagosilver.com/winn.htm for examples of Winn’s work. 10 Analysis of Eda’s work from 1904 through 1905 is based on the sketches and notes in her Sketch and Ledger Book, 1904–05 and corresponding black-and-white photographs in an undated photograph album, lists of works she showed at exhibitions recorded in catalogues published by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Detroit Museum of Art, and the occasional review of these shows in newspapers and periodicals. 11 See Sketch and Ledger Book, 1904–05. 12 When Marguerite Ogden Bigelow (1883–1928) purchased the necklace from Eda she was a student at Northwestern University and a fledgling author and poet. “Marguerite Ogden Bigelow,” The Anchora of Delta Gamma 29 (June 1, 1913), 301. 13 Sketch and Ledger Book, 1904–05, p. 6; and Photograph Album, undated, p. 9 #10, middle of left page. 14 Eda L. Young arrived in England on June 11, 1905. Incoming Passenger Lists, Ancestry.com. 15 Laurence Belmont Dixon, “A Brief History of My Family,” April 1944, 7, Laurence Belmont Dixon Papers, 1893–1944, Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego, Mss. 49, Box 1, Folder 1; Thomas S. Hines, Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 231. 16 “Treat for Artists: Arts and Crafts Society has Fine Exhibit,” c. 1907, in Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, Scrapbook, 1904–1913, Center for Creative Studies records, 1906–1982, Archives of American Art, reel D281. 17 Stephen Pudney, “Alexander Fisher: Pioneer of Arts & Crafts Enameling,” Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 to the Present 23 (1899), 74–75. In Great Britain, Alexander Fisher (1864–1936) was the key figure in reviving the art of enameling during the Arts and Crafts period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a major influence on American silversmiths who employed enamel. Fisher’s writings about his enameling techniques, “The Art of True Enamelling upon Metal,” were published by The Studio, Part I in 1900, Part II in 1901, and Part III in 1902. 18 Sketchbook: London, February 1906, Sketchbook: London, June 1906, Small Sketchbook: London; Small Sketchbook II: London, February 1906. 19 Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 14; and Photograph Album 1, p. 34, # 57. 20 Catalogue: Second Annual Exhibition of Applied Arts, Detroit Museum of Art, November 21 to December 12, 1905, p. 14, in Center for Creative Studies records, reel D281; Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of the Third Annual Exhibition of Original Designs for Decorations and Examples of Art Crafts Having the Distinct Artistic Merit, December 5, 1905, to December 21, 1905 (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1905), 52. 21 “Financial rec. school,” October 30, 1906, Center for Creative Studies records, reel D281. 22 On December 8, 1906 the Society made a consignment payment to Eda in the amount of $20, indicating that something she had made was sold. Ledger, December (continued), p. 8, and Ledger (Consignors), p. 25, in “Financial rec. school,” 1906, reel D281. 23 In the spring of 1907, Eda exhibited at the Special Exhibition of Handwrought Metal, Jewelry, Enameling and Village Industries held at the Arts and Crafts Society of Detroit, and in November, she participated in an exhibition of English and American silverware, jewelry, and enamels organized and held at the Society. “Arts and Crafts Society of Detroit, Mich.; Special Exhibition of Handwrought Metal, Jewelry, Enameling and Village Industries,” Keramic Studio 8 (April 1907), 282–83; “Treat for Artists: Arts and Crafts Society has Fine Exhibit,” and Announcement, “Rare Treat for Arts and Crafts: Some of the Finest Samples of English Workers to be Exhibited in Detroit,” Center for Creative Studies records, reel D281; “Exhibition Note,” Keramic Studio 9 (November 1907), 172. 24 Mrs. E. Young departed England on September 19, 1908. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890–1960, Ancestry.coma. 25 “Life and Letters,” Poet Lore 14 (Winter 1903), 110–11. 26 Art Institute of Chicago, Seventh Annual Exhibition of Original Designs for Decorations and Examples of Art Crafts having Distinct Artistic Merit, December 8, 1908, to December 22, 1908 (Chicago: AIC, 1908), 68, nos. 837–840. 27 Sketchbook: London, June 1906, p. 16. 28 Ibid., pp. 4-8, 14. 29 Eda’s working drawings for the back and front of the hand mirror are on yellow tracing paper, glued into Red Design Album, pp. 73–74. There are two identical graphite sketches of the lily pad enamel design in a rondel on pp. 55 and 57 and one in Green Design Album, p. 109. 30 Detroit Museum of Art, Architectural Exhibition: Detroit Architectural Club and The Society of Arts and Crafts (Detroit: Detroit Museum of Art, 1909), nos. 407–41, n.p. 31 They were married in 1909. Thomas Lord, Bruce Brady Wyckoff Lord Family Tree and 1910 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com. 32 This necklace appears in Eda’s Photograph Album 1, undated, as # 284, p. 26 and the sketch for the design is in Red Design Album, p. 23. 33 Image, Sketch of Necklace in South Kensington Museum (now V&A), Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 36. The sketch resembles the necklace in Fig. 6, which was acquired by the Indian Museum in London in 1855. Much of the contents of the Indian Museum was transferred to the South Kensington Museum in 1879–1880. We thank Jalena Jampolsky, American Wing Tiffany & Co. Curatorial Intern; and Nicholas Barnard, Curator, South and Southeast Asia, and Sue Stronge, Senior Curator, Asian Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, for their research and insight regarding Indian works in the V&A’s collection. 34 Cook County, Illinois, Marriages 1871–1920, Ancestry.com; Findagrave.com; 1900 US Census, Ancestry.com. 35 Daily Inter Ocean [Chicago] (October 17, 1866), 2, Genealogybank.com. 36 Dixon, “A Brief History,” 7; Richard Belmont Dixon, “Gleanings,” c. 1988, p. 11, courtesy of James Dixon; “Dinsmore Buys Another Grove,” Riverside Independent Enterprise [California] (April 7, 1909), 8. 37 Dixon, “Gleanings,” 10. 38 Ibid., 9. 39 Both Eda and Laurence continued to be members of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston through 1924. Laurence remained a member one more year, discontinuing his membership in 1926, the year Eda died. Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Annual Report of the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston, Massachusetts (Boston: Society of Arts & Crafts), 1911–1927. 40 “With the Societies: Detroit,” Handicraft 3 (January 1911), 383. 41 Email from Jim Dixon to Lori Zabar, March 30, 2015. The Dixons’ son Richard described another commission for finger bowls in “Gleanings, 10: “I recall their once making twelve finger bowls for one woman. They were of silver with a cloisone [sic] enamel plaque in the bottom of each. The plaques were all different each being a conventionalized design of a State flower, a State where she had lived or visited.” Graphite sketches for the twelve floral enamel plaques and watercolors for eight of those are in the Green Design Album, pp. 111–12. The name of the client is not indicated. 42 Laurence and his father, Laban Beecher Dixon, an architect, traveled through Japan from September 12 to November 14, 1905. They traveled in rural regions, avoiding westernized areas. Laurence’s photographs and other materials are in the collection of the University of California, San Diego, Laurence B. Dixon, Papers, MSS 49. 43 Spring Announcement, 1912 in Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, Scrapbook, 1904–1913, reel D281. 44 Katherine McEwen, Chairman, “Report of the Exhibition and Lecture Committee,” in Seventh Annual Report of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit for 1914, Michigan, reflecting 1912–1913, 5. 45 Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Annual Report (1913), 33. 46 Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Annual Report for the Year 1920 (1921), 18. 47 Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Annual Report (1914), 12. 48 Wilhelmina C. Knowles, “Arts and Crafts,” House Beautiful 37 (February 1915), 84. 49 Photograph Album 1, p. 45. 50 “Arts and Crafts,” House Beautiful 37 (April 1915), 146–47. 51 Hazel H. Adler, The New Interior: Modern Decorations for the Modern Home (New York: The Century Co., 1916), p. 11. 52 Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, Annual Report for the Year 1916 (1917), 20. 53 Florence N. Levy, American Art Annual 13 (New York: The American Federation of Arts, 1916), 95. 54 Artists Guild, An Illustrated Annual of Works by American Artists & Crafts Workers 1915–1916 (Chicago: Artists Guild, [1916]), 15, Google.com; Artists Guild, A National Association of Artists and Craft Workers (Chicago: Artists’ Guild, 1917), n. p., Chicago Silver.com. 55 Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of the Fifteenth Annual Exhibition of Applied Art and Original Designs for Decorations (Chicago: October 12–November 15, 1916), 30–31, courtesy of Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago. 56 “Winter Announcements 1917–1918: Calendar of Events, November,” in Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit, Scrapbook, 1915–1918, Center for Creative Studies records, reel D282. 57 Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of the Eighteenth Annual Exhibition of Applied Arts (Chicago: AIC, October 7–26, 1919), nos. 276–78, courtesy of Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago. 58 Green Design Album, p. 41. 59 Autumn Bulletin, Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit (October 1920), 2, Center for Creative Studies records, reel D282. 60 Deaccession Records, Cranbrook Archives, Center for Collections and Research, Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; City of Detroit, Annual Report for the City of Detroit for the Years 1919–1920, 467. 61 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Tricennial Exhibition of the Society of Arts & Crafts in Celebration of the Thirtieth Anniversary of its Organization, March 1–March 20, 1927 (Boston: D. B. Updike, The Merrymount Press, 1927), 7, catalogue nos. 86, 87. 62 Presumably, the hand mirror and box were included in the New York show. “Gallery Exhibitions,” Bulletin of The Society of Arts and Crafts 11 (May 1927), n.p., courtesy of Kim Tenney, Curator of the Arts Department, Boston Public Library. 63 Emails from Leslie S. Edwards, Head Archivist, Cranbrook Archives, Center for Collections and Research, Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI, to Lori Zabar, citing Detroit Arts Commission minutes dated November 30, 1944. According to Maria Ketchum, archivist at the DIA, the Arts Commission meeting date was November 27, 1944. See emails in American Wing scholarship files. 64 The hand mirror sold for $625 and the jewel box for $275. The Cranbrook Collections, Sotheby Parke-Bernet New York, May 2–May 5, 1972, sale no. 3360: Hand Mirror, Lot 9 [illustrated] and Silver Covered Box, Lot 34. 65 Sotheby’s, New York, December 18, 2013, sale no. 9058, lot 100. 66 Sotheby’s, New York, March 2, 2016, sale no. 9474, Lot 103. The sellers of the silver covered box were Jules and Gladys Reiner, who had purchased it at the Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet sale in 1972. 67 Sketch and Ledger Book, 1904–05, pp. 14, 16. 68 Dixon, “Gleanings,” 10. For examples of knitted bead bags by Eda see Photograph Album 2, p. 22, #159, and p. 28, #291. 69 Handbag Frame, Green Design Album, p. 92. 70 See design for the handbag frame in Green Design Album, p. 97. 71 A sketch of a similar goblet appears in Eda’s Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 15, and her design for the present goblet is in Red Design Album, p. 61. 72 Autumn Bulletin, Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit (October 1920), 2, Center for Creative Studies records, reel D282; a “Cup, silver and enamel” was shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, Nineteenth Annual Exhibition of Applied Arts (Chicago: AIC, March 8–April 5, 1921), no. 120. 73 Metropolitan Museum of Art, Exhibition of American Handicrafts Assembled and Circulated by The American Federation of Arts 1922–23 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 1–31, 1923), 6, no. 34(b). 74 Richard Dixon to Mary Dixon Howard, December 25, 1997, courtesy of Mary Dixon Howard, Washougal, WA. 75 Dixon, “Gleanings,” 10. 76 Photograph Album 1, p. 20, # 26. 77 Art Institute of Chicago, Nineteenth Annual Exhibition of Applied Arts and the Exhibition of British Arts and Crafts (Chicago: AIC, March 8–April 5, 1921), no. 119. 78 Richard Dixon to James and Shelly Dixon, December 25, 1997, courtesy of James Dixon. 79 Eda’s sketches include “Designs from China in B.M.” in Sketchbook: London, February 1906, p. 55; and “Two cloisonné enameled / mountings for Chinese embroidery / bag,” ibid., pp. 13, 14. 80 Red Design Album, p. 23; Photograph Album 1, pp. 24, 45; Green Design Album, p. 23. 81 There is a design for the gold filigree bracelet in the Green Design Album, p. 85, with and without enamel, including prices and a photograph in Photograph Album 2, p. 37. 82 Sketchbook: London, June 1906, p. 37. 83 “Dixon Sells Home,” Riverside Daily Press (November 12, 1925), 2. 84 Dixon, “A Brief History,” 7. 85 “Artists of the City Exhibit Work; Riverside Has an Interesting Group of Artistic People,” Riverside Daily Press (January 24, 1927), 7. Eight years after Eda’s death, Laurence, at age 60, married Eda’s sister, Margaret Lord, 41, in 1934. “Marriage Licenses,” Evening Tribune, San Diego, CA (October 20, 1934), 12.