Last Friday, a crowd of mostly students and professors gathered at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture to hear a series of talks on design topics ranging from experimental architecture to computer interfaces. Despite the conference title, Failed Design (and subtitle: “What were they thinking?”), most speakers described design stories of some success or at least mitigated failure. Daniel Barber of Columbia University described ventures into environmentally efficient architecture in the 1950s, including a series of modern “solar houses” and the MIT research team Victor and Aladar Ogyay’s calculations for non-mechanical climate control. These ventures may not have been adopted in any major way, but they were successful in creating non-governmental organizations to promote the cause.

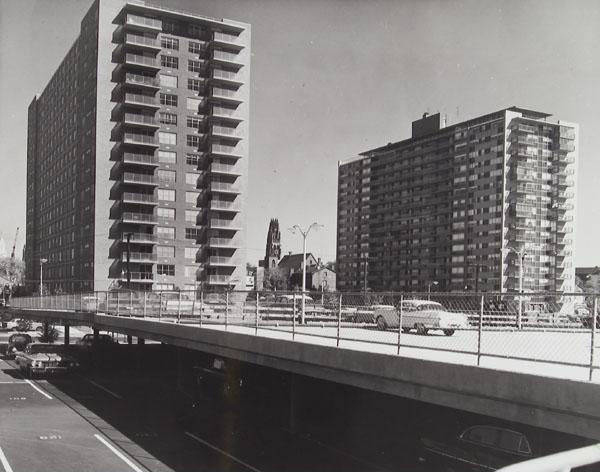

Then there was the Towers complex in New Haven, a pair of apartment buildings designed as part of a large-scale urban renewal project in the 1950s and 1960s. As Yale University’s Francesca Russello Ammon noted, they never achieved the city’s stated goal of luring suburbanites back into the urban core, however they are still inhabited—evidence of at least partial success.

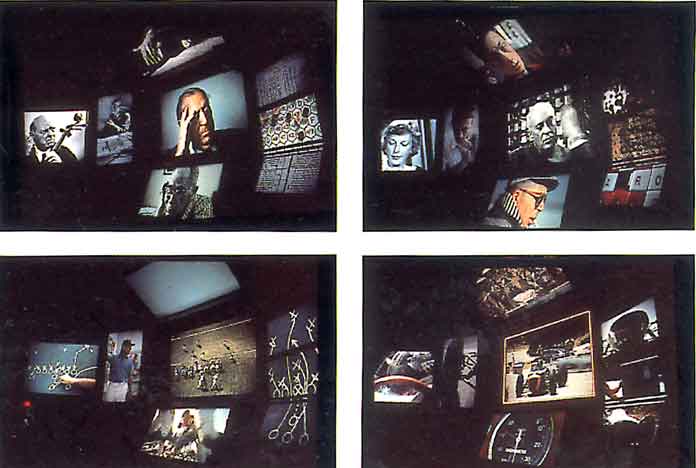

The structure of the symposium itself was flawed: each speaker answered questions after their own talk, instead of moderated questions as a panel. As a result, there were only offhand references to connections between the talks, such as John Vines’s paper on current Human-Computer Interaction models and Jesse Stein’s study of Charles and Ray Eames’s design for the IBM pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. Vines considered how older users operate (or don’t) new computer interfaces, while Stein contended that the Eames’s Think projections—a multi-screen series that compared human decision-making to computer calculations—did little to explain the new technology to a popular audience. A discussion of how computers inform or confuse us could clearly be fodder for an interdisciplinary conference of its own.

Between these discussions of design failures, a successful designer offered his own perspective in a keynote address. William Drenttel spent a decade in advertising before launching his own studio in partnership with his wife, Jessica Helfand. Drenttel presented his experience as an alternative to what he sees as a failed model—the “Robin Hood” approach to design, in which designers siphon money from their projects for large corporations to pay for pro-bono side work. Drenttel has instead become something of a design entrepreneur, launching his own press in partnership with Helfand, establishing various online information projects including DesignObserver.com, and working with organizations (both as a designer, and as a board member) including the National Poetry Foundation and Teach for All. Drenttel advocates a more integrated role for the designer in social projects—not just designing the Web site, building, or interface, but being engaged in the mission and planning of these programs on a long-term basis. Drenttel reminded critics and historians that many people and institutions play a part in a design, and that their collaboration often determines success or failure.