Fig. 1. Panoramic View of New York Taken from the North River by Robert Havell Jr. (1793–1878), 1844. Inscribed “Drawing & Engraved by Rob-t Havell” at lower left, “Printed by W. Neale” at lower right, and “Entered According to Act of Congres…1844 by Rob-t Havell…New York/ Published by Rob-t. Havell, Sing Sing, NY/ and Wm. A. Colman, 203 Broadway/ Ackermann & Co. 96 Strand London” at bottom center. Hand-colored etching and aquatint, 13 7/8 by 32 5/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps, and Pictures, bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold.

Henry Hudson was disappointed by the river that bears his name: it didn’t lead to the Indies as he and his Dutch clients had hoped in 1609. In the centuries that followed, however, the river has often been at the center of events, trade, and trends that have shaped the American nation.

During the Revolution, the British chose the river valley as the logical place to try to divide and conquer the rebellious colonies. Early in the nineteenth century, DeWitt Clinton’s brilliant concept for extending the waters of the Hudson to the Great Lakes with a man-made canal opened up the North American continent to development, and the young republic, previously constrained to the coast by the Appalachian Mountains, began a dramatic westward expansion.

Figs. 2–5. Hudson River Day Line souvenir pennants. Hudson River Maritime Museum, Kingston, New York.

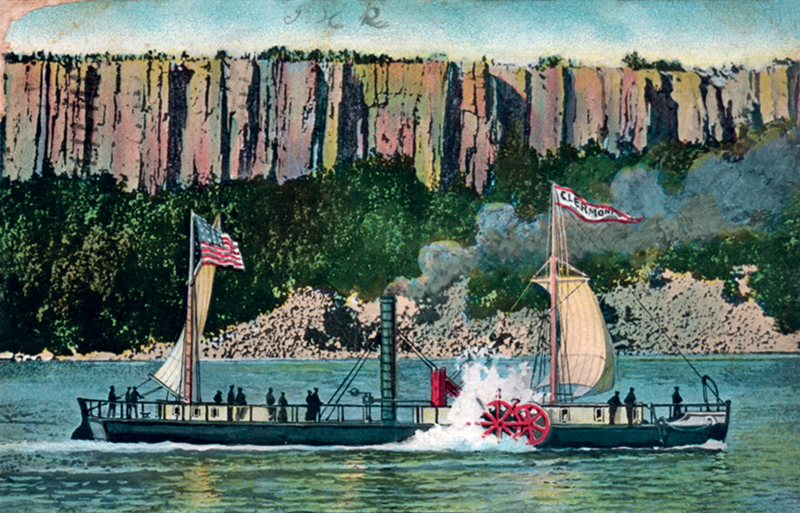

A key element in the country’s transformation was Robert Fulton’s development of the first commercially successful steamboat. On August 17, 1807, the Clermont—as the ship would eventually be named, in honor of his partner, Chancellor Robert Livingston’s Hudson valley estate—set out on its maiden voyage from the west side of Manhattan. A skeptical crowd gathered to jeer her off, thinking the smoking vessel would likely explode. But Fulton, alone and steady at the helm, kept the boiler under control and chugged off upriver. Twenty-four hours later he landed at Livingston’s dock, and then continued on to Albany the next morning, the travel time totaling thirty-two hours. This day-and-a-half journey between New York and Albany—compared to the often seven-day trip in a sloop powered by wind—marked the beginning of the steamboat era on the Hudson, a phenomenon that would quickly extend to other American rivers, coastal waters, and, eventually, to transatlantic travel.

Fig. 6. The Clermont was the first practical steamship, built by Robert Fulton in 1807. It was also the first steam-propelled vessel to go up the Hudson River, on August 17, 1807, on its historic trip from New York to Albany, as depicted on this vintage postcard. Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Fulton and Livingston had a lock on the Hudson steam service until 1824 when, in the famous case of Gibbons v. Ogden, the Supreme Court ended the monopoly as an inappropriate restriction on interstate commerce. Thereafter, competitors fought furiously for the growing market for steam transport. Prices dropped, speed picked up, and safety was neglected, with sometimes fatal consequences. Entrepreneurs sought to attract travelers with sumptuous and extravagant steamers with lavish staterooms, grand public interiors, good food elegantly served on real china, and amusements ranging from cotillions to elaborate funerals. These floating palaces became symbols of American ingenuity, affluence, and, sometimes, naughty behavior. (A conference of New York religious leaders reportedly convened to counter the fall-off of attendance at church by families preferring Sunday steam excursions.) Later-hour departures were especially suspect, and newspapers warned of the drinking, gambling, and loose women on those trips to Albany and Fall River.

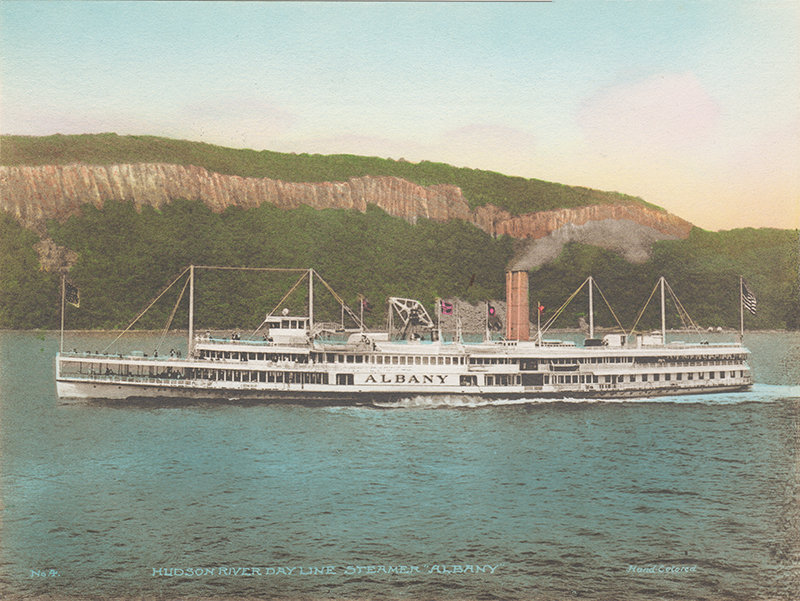

Fig. 7. Hudson River Day Line souvenir postcard depicting the Albany, built in 1880 and in operation until 1930. Hudson River Maritime Museum.

As America became more sensitive to the inevitable despoliation of the natural landscape consequent to the industrialization of what had once been seen as a hostile wilderness, a generation of poets, writers, and painters began to celebrate the splendor and spirituality of nature. The Hudson valley became not only a route to the West but an object of veneration: a unique place that had to be seen by European tourists if they were to understand America; a natural setting for the great rural estates of leading figures of finance and industry eager to display their patrician sensibilities; and a healthy recreational escape for the urban poor who were otherwise condemned to smoky and congested neighborhoods.

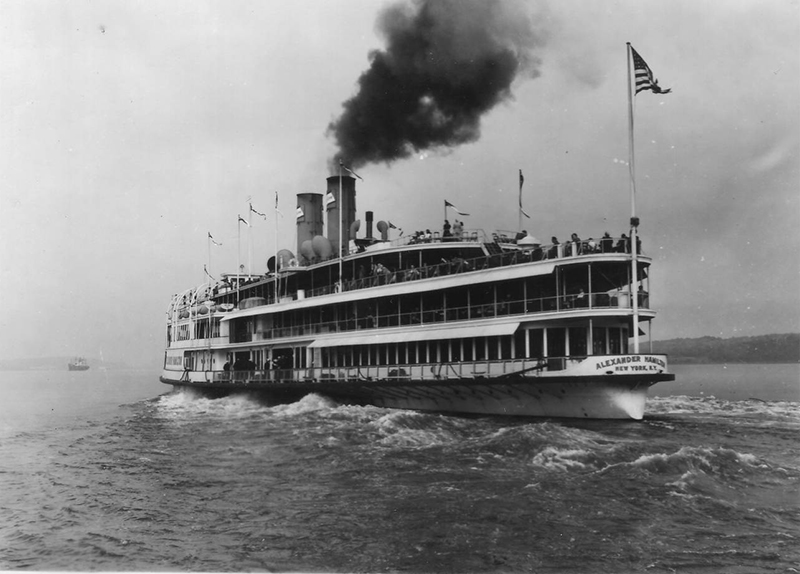

Fig. 8. The Alexander Hamilton passing Bear Mountain, as shown on a Hudson River Day Line souvenir postcard from the 1960s. This steamer was originally built in 1924 and was in operation until 1971. Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Something magical about the steamer—perhaps its graceful lines and quiet propulsion—suited it for communion with the beauty of nature, especially compared to the noisy steam locomotive. In any case, the era’s leading arbiters of taste acclaimed that not only was the Hudson scenery superior to that of the Rhine and other celebrated European attractions, but there was no more satisfying way to take it all in than from the deck of a Hudson River steamboat gliding noiselessly past the Palisades or through the Highlands.

Fig. 9. A stern-side view of the Alexander Hamilton in a photograph of 1940. Hudson River Maritime Museum.

Sadly, this glorious experience came to an end in the 1970s, when the last Hudson River Day Liner, the Alexander Hamilton, was retired. In an era when such icons as Penn Station and the old Metropolitan Opera and the Twentieth Century Limited were disappearing, the loss seemed almost inevitable. The Hamilton sat for a while at South Street Seaport, costly to maintain, and was later moved as part of some restaurant venture to Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey, where a violent storm took her to the bottom.

That might have been the end of the story.

Fig. 10. Columbia in its heyday ferrying passengers in Detroit, taken from the Ambassador Bridge, c. 1947. Courtesy of the SS Columbia Project, New York.

But, happily, across the river from South Street Seaport in Brooklyn Heights a young boy grew up fascinated by the constant parade of vessels in the harbor. By the time he was ten, Richard Anderson was a volunteer at the South Street Seaport Museum and an acolyte of the Seaport’s charismatic leader, Peter Stanford. Along with his wife, Norma, Stanford had rescued the city’s historic Fulton Fish Market, and was in the process of finding and restoring a fleet of historic ships. From him, young Anderson caught the bug.

Years later, after successful stints in banking and a second career as an art dealer, Anderson became focused on the idea of restoring steam service on the Hudson. The savvy New Yorker and the (as she first seemed) sorry old SS Columbia were brought together by the National Trust for Historic Preservation; the nonprofit had saved the ship from slow deterioration in Detroit, where she was lying untended after retiring from almost ninety years as an excursion boat to the popular Boblo Amusement Park on Bois Blanc Island, Ontario. Anderson realized that while Columbia had the graceful lines of the nineteenth-century steamers (she had in fact been designed by Frank E. Kirby and Louis O. Keil, who had created the Alexander Hamilton and other great steamers for the Hudson River Day Line), there was a critical difference: Columbia was built with a riveted steel hull and main deck. The internal superstructure of the deckhouse was also steel, which served to support the wooden upper decks, bulkheads, and fancy design flourishes. The innovative use of large steel girders had even allowed the designers to install a vast open dance floor. It was a modern ship, run-down but sound.

Fig. 11. Passengers boarding Columbia from the Boblo Amusement Park in Ontario, in an undated photograph. Courtesy of the SS Columbia Project.

Under Anderson’s leadership, the SS Columbia Project was formed, a board was elected, and they acquired the ship and recruited a first-rate maritime restoration team. It was critical for the team to have experience and credibility that could pass muster with the US Coast Guard (which is anything but casual about putting passenger boats in service). Though Anderson died before the ship left Detroit, the team he put in place and the solid organization he established kept the project moving.

The first priority in the restoration process was to stabilize the hull and deckhouse. Columbia was towed from Detroit to Toledo, Ohio, where several shipyards still have crews experienced with riveted vessels. After two tons of zebra mussels were scraped off the hull and 1,207 square feet of steel plates were replaced, Columbia was declared seaworthy for the trip across Lake Erie. She was brought to Buffalo, where she is now—securely berthed and experimenting with cultural events as a venue for theater, dance, a pop music festival, and a meeting place for artists as restoration nears completion. The next step in readying the boat for the long trip through the Saint Lawrence Seaway and down the Atlantic coast to New York City will be a comprehensive laser scan, so that every decorative and historic element—carved newel posts, varnished wood panels, etched glass, brass railings, the entire pilot house—can be removed for restoration, and later reinstalled.

Fig. 12. A tugboat towing Columbia to Buffalo, New York. Photograph © Gene Witkowski, courtesy of the SS Columbia Project.

It will take more funding, needless to say, but the foundations, government agencies, and individual donors who have helped bring her this far are encouraged by the business plan. Just sitting at the dock in New York, Columbia—as a distinctive catering and events venue with capacity that rivals hotel ballrooms—will earn enough to handle her maintenance and expenses. As reliable as this income may be, the real project, of course, is not to make a killing in the catering business but to get the steamer back on the river.

The Hudson valley that Columbia will tie together is not the one the Alexander Hamilton steamed into almost fifty years ago. The world-famous landscape then threatened by shortsighted projects has been secured through a series of heroic fights that gave birth to the modern American conservation movement. The once polluted waters have been cleaned up, and the sturgeon—and, one hopes, eventually, the shad—are on the rebound. Children along the river have become knowledgeable stewards of the water, thanks to pioneering education efforts in schools, which take students along streambeds and on the river itself aboard the Hudson River sloop Clearwater. The old river towns at their nadir in the middle of the twentieth century have come back to life in the twenty-first. Storefronts are restored, new restaurants—many relying on the resurgence of local farms—proliferate.

Fig. 13. Columbia has been docked in Buffalo since 2015, where she is undergoing repairs. Photograph © Gene Witkowski, courtesy of the SS Columbia Project.

Nothing is more telling than the incredible energy and activity of the arts community. Painters, composers, writers, dance companies, symphonies, galleries, historic houses, and museums are making the valley a great place to visit and a better place to live.

Until now, the Hudson valley hasn’t been easy to access. More than sixty million visitors come to New York City every year from overseas and elsewhere in America, and only a fraction of them ever make it up the river. What better way to introduce them to the valley that represents the continuum of the best of the American experience. Hail, Columbia!

KENT BARWICK is a preservationist who has been involved with the rescue or restoration of a number of significant landmarks including Grand Central Terminal, Radio City Music Hall, the Statue of Liberty, the United Nations Headquarters, Central Park, and the Park Avenue Armory.