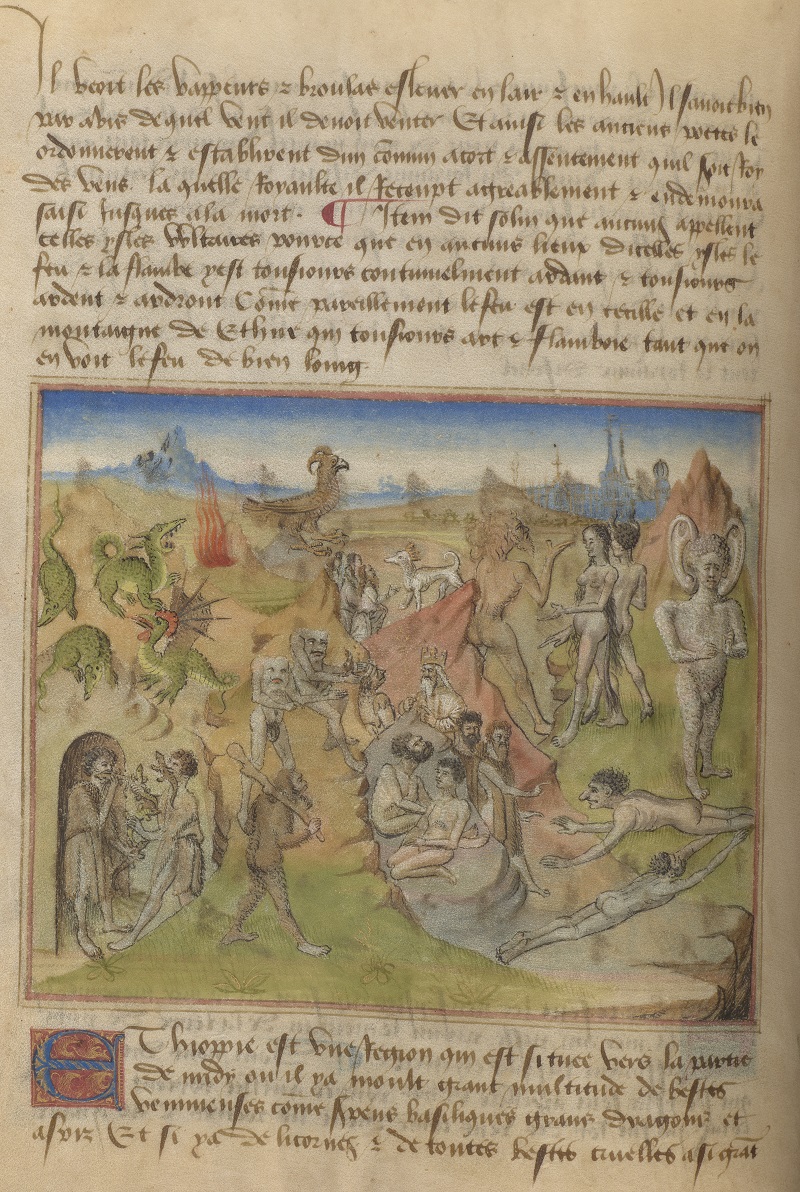

Ethiopia, from Livre des merveilles du monde (Book of the Marvels of the World) by the Master of the Geneva Boccaccio, a member of the Jouvenel des Ursins Group, France, possibly Angers, c. 1460. Pigment on vellum, manuscript page 11 by 8 3/4 inches. MS M. 461, fol. 26v. Morgan Library and Museum, New York; photograph by Janny Chiu.

A late medieval English prayer roll in the Morgan Library is a physical manifestation of the fears it claims to protect against: death in childbirth, fever, sudden death, false witness, wicked spirits, pestilence. And it is full of monsters. The saints called upon to protect the readers from peril are pictured calmly facing down all manner of ferocious beings. Saint Margaret, Saint Armagillus of Brittany, Saint George, and Saint Michael triumph over scaly dragons with, variously, bat wings, fangs, talons, multiple heads, and arrow-shaped tongues. Red-spotted griffins and miniature dragons creep among the vines that divide the roll into discrete sections, and fierce desert beasts menace John the Baptist. King Henry VI, included among the saints, is accompanied by his emblematic antelope: a wondrous spotted creature with a gleaming red eye, tusks, and jagged horns that could saw down a tree—at least according to medieval bestiaries. Should this noble beast also be considered a monster? It depends on how we define monsters.

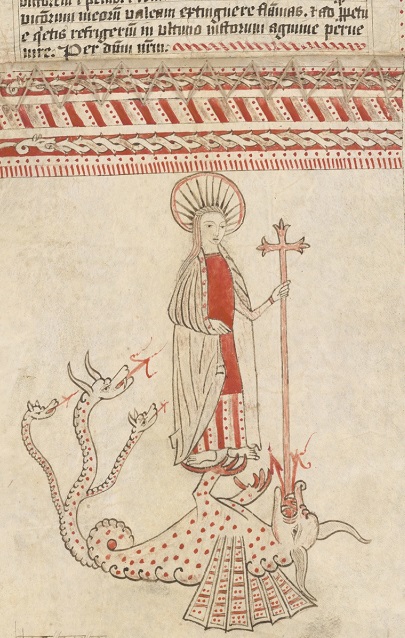

Saint Margaret, from a prayer roll attributed to Canon Percival, Yorkshire, England, c. 1500. Pigment on vellum, manuscript overall 19 ¼ feet by 7 ¼ inches. MS G. 39. Morgan Library and Museum, gift of the trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection; photograph by Graham S. Haber.

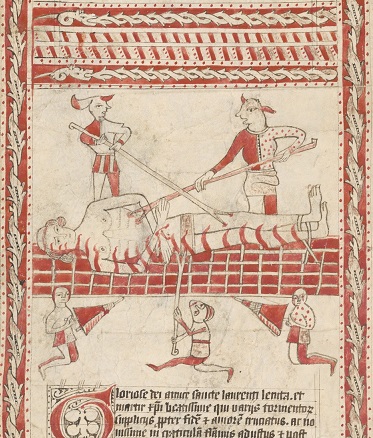

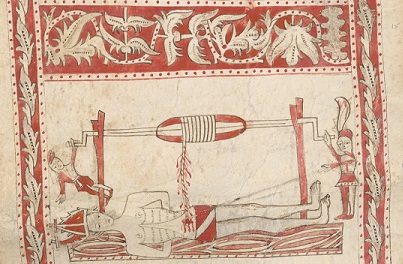

One defining characteristic of monsters is that they are hard to define. A monster defies categories; it is often part one thing, part another. More than and/or less than human or animal, sometimes the only way we know something is a monster is the way it makes us feel: terrified, revolted, uneasy, awed—even curious and delighted if the threat does not seem immediate. If we return to the prayer roll with a broad and open-ended definition of monsters, even some of the saints start to seem to have monstrous qualities. Are giants monsters? If so, is Saint Christopher, the sacred Christ-bearer shown in the prayer roll using an uprooted tree as a staff, a monster—or at least, “monstrous”? (In some depictions, Christopher is also shown with a dog’s head.) What about the hybrid creatures that symbolize the Evangelists, flanking the crown of thorns and nails at the top of the scroll? Mark’s lion is shown with a human head on a furry lion’s body, with wings, and ferocious red claws. Monstrous? Further along in the roll, John the Baptist wears a spotted, camel-hair mantle that gives the impression that the saint has extra hooved limbs and a second head, with an open eye and flame-like tongue. This extraordinary garment lends the saint an imposing air of monstrous sanctity. And there are other disturbing beings in the roll that don’t seem quite human, and which might, indeed, be called monstrous. The torturers of Saints Erasmus and Lawrence are shown disproportionately small in comparison to the saints’ imposing, dignified bodies. In contrast to the stoic saints, they are ghoulishly animated, leaping about as they unwind Erasmus’s intestines from his body and stoke the flames beneath Lawrence’s grill. They have bizarre, mismatching clothes, with extravagant feathers and patterns. Two of Lawrence’s torturers have gaping mouths and overlarge noses that evoke hideous stereotypes of Jews, common in medieval art, which would undoubtedly have been familiar to readers of that day. Monstrosity, then, can signal terrible beasts, sacred majesty, and hateful stigmatization of the disenfranchised other.

Saint Lawrence, from the Canon Percival prayer roll, c. 1500. Haber photograph.

This prayer roll is one of the manuscripts featured in an exhibition examining the difficult issues surrounding monsters and monstrosity in medieval art at the Morgan Library and Museum. The prayer roll introduces the section on “Terrors,” which argues that dominant institutions and rulers used the aesthetics of monstrosity to enhance their authority. Made by a priest named Percival (or Percevall), it demonstrates the power of the Church to control the awesome amuletic powers attributed to it, to protect the faithful from the monsters that lurk in the margins and challenge the saints. The roll pictures rulers as partners with the Church in this endeavor: by including Henry VI among the saints; by showing Henry, God, and Saint Margaret wearing the same crown; by including saints associated with Henry VII—king when the scroll was made—such as the obscure Saint Armagillus.

Saint Erasmus, from the Canon Percival prayer roll, c. 1500. Haber photograph.

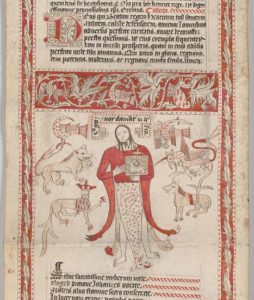

The second section is titled “Aliens,” a word derived from the Latin word for “foreign” or “exotic,” and it examines how the aesthetic of monstrosity operates in medieval art to distinguish between insider and outsider—to establish and enforce ideas about normativity. The section opens with a splendid fifteenth-century French manuscript of the Livre des merveilles du monde (Book of the Marvels of the World). The manuscript contains more than fifty images of locations, some close, some distant, and a few utterly fantastic. The image of Ethiopia is paradigmatic of the exoticizing approach of the illuminator. Crammed into its densely packed space are lizard-eating cave dwellers, naked philosophers, a club-wielding wild man, a large-eared furry giant, dragons, the horned bird of Tragopa, blemmyes—headless creatures with faces in their chests—and more. Their detailed style invites close examination, which reveals points of difference from their intended audience—French Christians. The most obvious differences are the bodily ones. Most of the figures are human or more or less humanoid, but they deviate from the norm that is clearly their prototype through excess and lack: too much body hair, oversize ears, oversize bodies, missing heads. They also, though, defy European expectations through their behavior. These alien peoples eat strange foods, wear strange clothes (including animal skins), and ignore basic social regulations common in medieval Europe: women stand about in public fully nude, calmly conversing with men as if nothing is amiss. For medieval Christian audiences, perhaps the most troubling element of the image is the vignette in the center of the scene, just in front of the giant bird of prey. Here, we see a group worshipping a crowned dog. It is not clear from the image whether this is a living dog or a sculpted idol, but in either case, this is a form of worship wholly outside of Christian practices. These various points of divergence all ultimately serve to define and enforce what this manuscript is establishing as “normal” through systematic negation thereof.

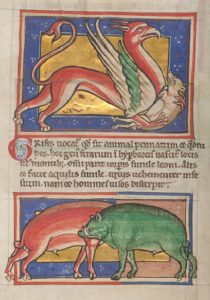

Hydra, from the Worksop Bestiary, English, possibly Lincoln or York, c. 1185. Pigment and gold leaf on vellum, manuscript page 8 ½ by 6 inches. MS M.81, fol. 16r. Morgan Library and Museum; Chiu photograph.

Griffin and Boars, from the Worksop Bestiary, c. 1185, fol. 36v. Haber photograph.

While these peoples and creatures are all presented as “marvels,” and they are as highly diverting to modern viewers as they likely were to medieval viewers, it is important to bear in mind that these marvels are not presented as fictions; they appear alongside images of France and Britain. The style of the images and texts is the same for the familiar and the exotic, and all are presented as part of the panoply of creation. We must therefore bear in mind that the club-wielding wild man, dog worshippers, and blemmyes are all presented to the European viewer as the actual inhabitants of Ethiopia. The manuscript evinces the same patterns of exoticizing, dehumanizing, and demonizing in its depiction of many regions of the world. This practice of presenting the inhabitants of Africa, Asia, and eventually the Americas as semi-human, subhuman, and outright monstrous had pernicious consequences as Europeans came into increasing contact with the real peoples of the globe, and frequently perceived them through the lens of monstrosity and otherness. This framework arguably paved the way for later colonial and imperialist abuses. If the people of a region are seen as not quite human, abuses are certain to follow.

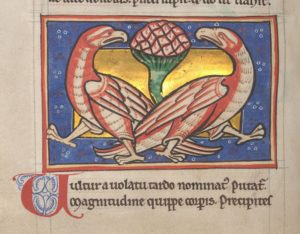

Vultures, from the Worksop Bestiary, c. 1185, fol. 48v. Chiu photograph.

The Livre des merveilles du monde turns most groups it presents into strange, alien beings, even those relatively close to home. Taken as a whole, they comprise through negation an image of the normative—not that which is common, but that which is culturally valued, approved, and desired. The normative is, in many cultures, anything but normal. In addition to images of distant groups, the “Aliens” section considers a range of identities criticized, condemned, and rejected by the powerful elites of medieval European society. These individuals and groups include Jews, Muslims, the physically and mentally impaired, the poor, people of non-normative genders and sexualities, and even women. Taken together, of course, these people far outnumbered the white, Christian, wealthy, able, straight rulers of civic and religious institutions who determined so much about their fates.

The third and final section, “Wonders,” explores the power of monsters to unsettle expectations, to embody contradictory ideas, and to create a space for the imagination at the boundaries of the knowable. The manuscript introducing this section is the Morgan’s famed bestiary, made for an Augustinian priory in Worksop, England, in the twelfth century. As much devotional books as natural history, bestiaries integrated knowledge gleaned from ancient and early Christian sources. They were designed to reveal the wonder of creation—to make sense of divine meanings medieval people believed were invested in the natural world. The mixture of fabulous and real beasts—commonplace and esoteric knowledge—blurred the boundaries between fact and fiction.

Gaul (France), from Livre des merveilles du monde, c. 1460, fol. 33r. Chiu photographs.

For example, after identifying the hydra as a multiheaded dragon, locating it on the island of Lerna (province of Arcadia), and explaining that its Latin name is related to the beast’s ability to regrow lost heads, the bestiary tells us that the hydra is a fable. It explains that “hydra” is the Greek word for water and references, not a monster, but a difficult-to-control body of gushing water on Lerna—closing off one source of the flood caused more to burst open. The hero Hercules drained the marsh and thus closed all of the water spouts. The learned details provided create a kind of reality effect. The hydra may be a fable, but Hercules is presented as real, as are the dragons, griffins, basilisks, unicorns, and other wondrous animals in the book.

Britain, from Livre des merveilles du monde, c. 1460, fol. 6v. Chiu photographs.

Interleaving such wondrous beasts with more familiar animals makes the ordinary seem unfamiliar—an effect intensified by the arcane knowledge provided to encourage readers to marvel at all of God’s creation. Thus, a griffin shares the page with two boars—one fabulous, the other found in England—though the boars are made strange and interesting by their unnaturally bright coloring.

Henry VI, from the Canon Percival prayer roll, c. 1500. Haber photograph.

A devotional book that offers animals as moralized examples and anti-models for human behavior, the bestiary was also a scholarly enterprise: it cites evidence from authoritative texts, parsing etymological evidence, presenting contradictory information and counterarguments. So, for example, the vulture was thought to conceive without conception, and is thus an emblem of the Immaculate Conception. As a carrion eater, it was associated with Christ, who looked down, saw the corpse of human mortality, then descended to earth. And yet, in some versions of the bestiary, the scavenger is likened to a sinner who follows the devil’s army. That bestiaries provide multiple, and sometimes opposing, interpretations for many of the beasts, reflects medieval reading practices: readers were encouraged to meditate slowly and carefully on the texts and images before them.

Crown of Thorns, from the Canon Percival prayer roll, c. 1500. Haber photograph.

Saint John the Baptist, from the Canon Percival prayer roll, c. 1500. Haber photograph.

The guiding metaphor for the thoughtful reading practices of the Middle Ages was ruminatio, the Latin origin of the modern English “rumination.” To ruminate, literally, is to chew a cud, as a cow does. This is an agrarian metaphor that would have been particularly meaningful in an age when life was largely rural, and livestock familiar. A ruminant chews the cud because it eats grasses, which are barely digestible. Through their slow, repetitive chewing, they break down this difficult material, and eventually draw from it what they need to live. This was the goal of medieval reading and viewing practices. The manuscripts in this show—the three discussed here, and the additional fifty or so on view—and the many monsters they contain, reward our attentions, yielding excitements, horrors, and wonders for those willing to take a bite.