“Idleness opens up for any one who has eyes to see and a mind to dream a playground of infinite variety,” wrote novelist Arthur Pier in 1904 for the magazine Atlantic Monthly.1 William Merritt Chase had eyes to see the liberating benefits of idleness, and he found motifs of infinite variety in America’s playgrounds. Catching his subjects at rest or at play both in the city and in the country, he took delight in recording the oases of New York City’s parks, the joy of children’s games, and the unhurried contemplation of blue skies above a Long Island beach (see Fig. 2). From scenes of modern leisure, Chase created a modern American art.

The world of ease that Chase portrayed was new. A belief in the virtue of work, the value of labor, and the idea that mischief came from idle hands had been ingrained in American society, but by the late nineteenth century, the merits of free time began to be appreciated, at least by those who could afford it. “Work is good,” announced a writer for Scribner’s, “No one seriously doubts this truth…. But work is not the only good thing in the world.” The author added, “the god of labor…has a twin sister whose name is leisure…[which] has a value of its own. It has a distinct and honorable place wherever nations are released from the pressure of their first rude needs…and rise to happier levels of grace and intellectual repose.”2

In urban areas during the decades following the Civil War, with the rise of industrialization and a unionized workforce, work hours became regulated, days off required, and official federal holidays declared by Congress. Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s Day, and Independence Day were mandated in 1870, Washington’s Birthday in 1879, Decoration Day (Memorial Day) in 1888, and Labor Day in 1894.3 Along with sanctioned time off for workers, school calendars changed, in general allowing for longer periods away from the classroom during the summer months. What had started early in the century as a privilege for the landowning class had been democratized, and by the beginning of the twentieth century a vacation, or at least spare time, was increasingly available to workers from the middle and even lower middle classes.4

What was to be done with these newfound idle hours? A modern industry—the leisure trade—grew to support them, involving everything from the construction and operation of elaborate mountain and seaside hotels and resorts, accessible by steamship or newly built railroad and trolley lines (see Fig. 4), to the manufacture of hammocks—once meant for laboring seamen, now a potent symbol of summer repose—and folding camp furniture, no longer required by the army, but needed instead by a host of vacationers. Educators and social theorists were quick to expound on the intrinsic value of free time, explaining its beneficial effects on both the mind and the body (and, in the case of such enterprises as Chautauquas and various other Methodist camps, refreshing for the intellect and the spirit as well).

While their companions and models lounged in picturesque locations, artists’ vacations were different. They were always working, and soon exhibition halls were filled with canvases whose titles contained such phrases as “idle hours,” “dolce far niente” (Italian for “the sweetness of doing nothing”), “reflections,” and “at ease.” For Chase there was little time for proper repose, but he took his pleasure in the act of painting, for, as a writer for Harper’s Monthly noted, his “work is recreation and [his] recreation is work.”5 With the scenes he recorded of quiet moments of relaxation in backyards and gardens, parks and parlors, Chase became one of America’s most accomplished painters of modern leisure. His alluring images were made with his characteristic technical fluidity, and thus neither his subjects nor his handling of paint seems labored. His canvases conjure peaceful summer days; his carefully selected compositions and harmonious arrangements of color appear effortless. “Feel happy when you are painting,” Chase told his students, and he took his own advice (see Fig. 6).6

Fig. 5. Park Bench, by 1890. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 12 by 16 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Arthur Wiesenberger.

That aura of pleasure suffuses Chase’s work, and belies the effort he put into creating innovative paintings of modern life.7 He worked hard to make his art look easy. Born to a middle-class family in Indiana, Chase cobbled together the support of local businessmen to finance his art education in Munich. From 1872 to 1878 he studied at the Royal Academy there, mastering the dark, gestural brushwork of the Munich school and studying the work of the old masters. He sent his paintings back to New York for display, earning admiration even before he returned to the United States in 1878. He immediately took rooms in New York’s most prestigious studio space, the Tenth Street Studio Building, where he established himself at the center of the city’s art world and created an eclectic, European-inspired studio space that announced his reputation as a well-traveled bohemian and an imaginative, creative artist. Soon thereafter, he began to explore modern subjects of relaxation in an innovative style.

Fig. 6. Chase with a group of his students in a photograph of c. 1900. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Rockwell Kent Papers.

Among the earliest of these is a pastel, The End of the Season (Fig. 3). The medium itself, admired for its dry powdery finish and brilliant colors, was a declaration of modernism in the period, admired by the avant-garde for the way in which its sketch-like character called attention to the artist’s hand.8 Chase, cofounder in 1883 of the Society of Painters in Pastel, was a master of it. He probably made this complex composition during a summer visit to Holland; one critic described it as a “Continental watering-place, chairs and tables upset by the seashore, with a single lonely figure.”9 A woman, properly dressed in a becoming gown, sits at her ease, her idleness set against the distant labors of the fishermen whose boat rests on the strand. The black chairs, empty now of holiday visitors, cartwheel down the slope, a bold compositional choice that adds vibrant movement to this otherwise contemplative scene.

Chase continued to explore leisure in the mid- and late 1880s in a series of images of women in the public parks of Manhattan and Brooklyn (Fig. 5). These urban retreats were heralded as places not only of respite, but also of revival. The “real meaning of the word recreation…[is] recreation,” one journal announced. “No mere playground can serve the purpose of recreation in this truer, broader sense—the purpose of refreshment, of renewal of life and strength for body and soul alike.”10 Before the middle of the nineteenth century, however, women of a certain class and level of propriety would not have appeared in such a public setting alone. In the decades after the Civil War, urban life changed and women with it. The war years had required a new self-sufficiency among women and they would not relinquish it, turning their attention from war work to activism in humanitarian causes, artistic endeavors, and suffrage. Another notable shift was the ease and comfort in which an unaccompanied woman of good character could navigate the city to take part in a variety of socially acceptable activities. Department stores, public musical and theatrical performances (particularly matinees), lectures and recitals, restaurants, museums, and civic parks now offered new recreational spaces where women were welcomed as consumers and connoisseurs, and they took to the public sphere with alacrity.11

Fig. 7. The Game of Ring Toss by the R. Bliss Manufacturing Company, c. 1890. New-York Historical Society, Liman Collection.

A well-dressed young woman in a pink gown, black jacket, and stylish hat sits alone on a park bench in A City Park, which shows Tompkins Park in Brooklyn (Fig. 8). She is alert, turning to face and engage with the viewer, although Chase has blurred her features, perhaps in acknowledgment of the recommendations in contemporary etiquette manuals that advised women in public places to avoid catching the eye of a stranger. This park, groomed and cultivated, is a domesticated oasis; populated almost exclusively by women and children, its broad promenade ends in a view of the apartments on Marcy Avenue (a respectable residential neighborhood and Chase’s own).12 The setting, like Chase’s model herself, is modern, urban, and safe.

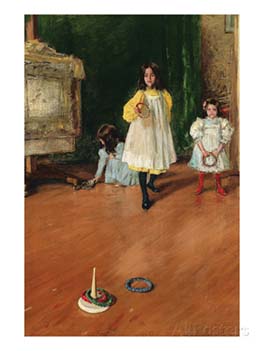

Leisure was also for children, and play time was newly credited with multiple benefits, serving to channel children’s energy in productive ways and to teach important life lessons. Books and articles suggested numerous appropriate activities, and commercial manufacture of games increased exponentially, alongside developments in the printing industry that allowed for inexpensive color reproductions. The R. Bliss Manufacturing Company, for example, founded in the 1830s to produce wooden screws, turned to games in the 1870s, applying color lithographs to wooden forms to make board games, blocks, toy boats and trains, doll houses, and beginning in the 1880s, lawn and parlor ring toss games, marketed for both boys and girls (Fig. 7). The game was considered so useful as a teaching tool that sets were distributed to schools in the 1890s; children were meant to learn patience, manual dexterity, and confidence from the activity.13 Chase showed three of his daughters intent on a match in his own studio, with one canvas on an easel and another on the floor (Fig. 1). His tipped-up composition, with its nearly empty foreground, was an entirely modern conceit, one based on the compositional possibilities set in motion by the camera, a device Chase called the “discovery of the century.”14

Fig. 8. A City Park, c. 1887. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 13 5/8 by 19 5/8 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, bequest of Dr. John J. Ireland.

Children and adults joined together for holidays at the beach, a motif Chase captured repeatedly in his images of the Long Island shore at Shinnecock, near Southampton (Figs. 9, 10). The town was one of the many new summer resorts that sprang up along the northeast coast in the 1880s and 1890s. Southampton lay “upon a narrow edge of inferior farm land between the once dreary sand hills of Shinnecock and a seashore indented with little bays.”15 Those dreary sand hills became the site of one of the first golf clubs in America, founded in 1891, the same year Chase was lured to Shinnecock to direct a summer art school founded as another part of a very deliberate program to build up the resort.16

Fig. 9. Morning at Breakwater, Shinnecock, c. 1897. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 40 by 50 inches. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection.

The same landscape that some had found inferior and dreary provided Chase with infinite subjects, for with his innovative approach to composition, any subject, no matter how modest, could inspire a great painting. Bold geometric patterns shape his view of the breakwater at Shinnecock, its rushing diagonal perspective contrasting with the diffuse scatter of figures on the beach. Children run and dig in the sand while women watch and read, sheltered by parasols or large Japanese umbrellas that add notes of color to the brilliant white sunlight. Figures are sketchy and abbreviated, the brushwork liquid and gestural.

These paintings by Chase praise a nation of relaxation, free from workplace cares and community concerns, at rest and at play. To depict these halcyon days, he employed the new painting of his age, ignoring narrative and celebrating everyday life. He devised inventive compositions that call attention to his artistry, telling his students, “don’t be too conscientious with your work-play with it more, be more artistic and free.”17 In Chase’s hands during the 1890s, modern leisure met modern art.

Fig. 10. At the Seaside, c. 1892. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 20 by 34 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot.

ERICA E. HIRSHLER is the Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the author of William Merritt Chase (MFA Publications, Boston, 2016).

1 Arthur Stanwood Pier, “Work and Play,” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 94 (November 1904), p. 670. This article complements the exhibition William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D. C., through September 11; at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from October 9 to January 16, 2017; and at Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, Italy, from February 11 to May 28, 2017; and its accompanying scholarly catalogue, Elsa Smithgall et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2016). See also the companion volume, Erica E. Hirshler, William Merritt Chase (MFA Publications, Boston, 2016). 2 Agnes Repplier, “Leisure,” Scribner’s Magazine, vol. 14 (July 1893), pp. 63, 64. 3 See senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/Federal_ Holidays.pdf (accessed July 4, 2016). See the discussion in H. Barbara Weinberg et al., American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885-1915 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994), pp. 92-94. 4 For further discussion, see Cindy S. Aron, Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States (Oxford University Press, New York, 1999). 5 John Gilmer Speed, “An Artist’s Summer Vacation,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 87 (June 1893), p. 3. 6 Marietta Minnegerode Andrews, as quoted in Ronald Pisano, A Leading Spirit in American Art: William Merritt Chase, 1849-1916 (Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, 1983), p. 88. 7 See Smithgall et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master for several discussions about Chase’s work and practice. 8 Marjorie Shelley, “Assimilating Modernism: The Pastel Technique of William Merritt Chase,” in Ronald Pisano, William Merritt Chase: The Complete Catalogue of Known and Documented Work, vol. 1 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2006), pp. 97-99. 9 “The William M. Chase Exhibition,” Art Amateur, vol. 16 (April 1887), p. 100. 10 “Playgrounds and Parks,” Garden and Forest, June 6, 1894, p. 221. 11 For some of the complexities of this discussion, see Kathy Peiss, “Going Public: Women in Nineteenth-Century Cultural History,” American Literary History, vol. 3 (Winter 1991), pp. 817-828. 12 Barbara Dayer Gallati, William Merritt Chase: Modern American Landscapes, 1886- 1890 (Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, N. Y., 1999), pp. 72-78. 13 Twenty-third Annual Report of the Board of Education of the Kansas City Public Schools (Kansas City, Mo., 1894), pp. 207-208. 14 “Original Notes of William M. Chase on His Talk to His Students in Phil. PA,” William Merritt Chase Papers, Archives of American Art, reel N69-137, frame 495. See also Smithgall et al., William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, p. 11. 15 Julian Ralph, “The Spread of Outdoor Life,” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 36 (August 27, 1892), p. 830. 16 See Cynthia V. A. Schaffner and Lori Zabar, “The Founding and Design of William Merritt Chase’s Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art and the Art Village,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 44, no. 4 (Winter 2010), pp. 303-350. 17 “Original Notes of William M. Chase on His Talk to his Students in Phil. PA,” reel N69-137, frame 507.

Fig. 1. The Ring Toss by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), c. 1896. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at upper middle right. Oil on canvas, 40 3/8 by 35 1/8 inches. The Halff Collection.

Fig. 1. The Ring Toss by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), c. 1896. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at upper middle right. Oil on canvas, 40 3/8 by 35 1/8 inches. The Halff Collection. Fig. 2. Idle Hours, c. 1894. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 by 35 1/2 inches. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

Fig. 2. Idle Hours, c. 1894. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 by 35 1/2 inches. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. Fig. 3. The End of the Season, 1884–1885. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Pastel on paper, 14 by 18 inches. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts, gift of Mrs. Dickie Bogle (Jeanette C. Dickie).

Fig. 3. The End of the Season, 1884–1885. Signed “Wm. M. Chase” at lower left. Pastel on paper, 14 by 18 inches. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts, gift of Mrs. Dickie Bogle (Jeanette C. Dickie). Fig. 4. Map of Long Island showing the Long Island Railroad, c. 1884. Color lithograph on paper, 7 1/2 by 21 inches. Library of Congress.

Fig. 4. Map of Long Island showing the Long Island Railroad, c. 1884. Color lithograph on paper, 7 1/2 by 21 inches. Library of Congress.