The work of Ronald Lockett, like that of Thornton Dial, Lonnie B. Holley, and others in the Birmingham-Bessemer circle, uses found materials to address environmental, historical, and political themes in ways that go beyond the usual categories.

Fig. 1. Ronald Lockett (1965–1998) standing outside his studio in Bessemer, Alabama, in a photograph by William S. Arnett, c. 1988–1989. Souls Grown Deep Foundation Photographic Collection, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The youngest member of what, in retrospect, we might embrace as the Birmingham-Bessemer [Alabama] school, Ronald Lockett produced a body of roughly four hundred works from the late 1980s until his death at age thirty-two in 1998. Over the course of that decade, he evolved a succession of styles that addressed core themes of ideal love, hope, frustration, spiritual faith, and redemption. He created works in series—for example, Smoke-Filled Sky, Traps, and Oklahoma—that explored histories of environmental ruin, domestic terrorism, and social and economic injustice, and also constructed singular compositions such as Poison River (Fig. 5) and Out of the Ashes. There are lighthearted moments in his work, such as Untitled (Elephant) (Fig. 2), but it is his steadfast commitment to visual explorations of a world in peril that defines his art. Lockett did not labor in a vacuum. He was deeply influenced by friends, family, and mentors, especially the late Thornton Dial. And, significantly, he influenced Dial in return.

Fig. 2. Untitled (Elephant) by Lockett, 1988. Wood sawhorse, metal wire, plastic vacuum-cleaner hose, industrial sealing compound, and enamel; height 30, width 54, depth 9 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta, Georgia, William S. Arnett Collection; except as noted, photographs are by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

Nearly two decades after his death, Lockett’s art is the subject of growing interest. The acquisition of one his Oklahoma series works by the Metropolitan Museum of Art through a gift from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, the development of a traveling exhibition of his work, and the publication of a collection of essays on his oeuvre and its contexts celebrate the arc of his creativity in a moment when conversations about American art are opening fresh perspectives. A key element in those exchanges focuses on contested perspectives of how we imagine “schools” of American art. Thus, we begin with what Lockett made in his truncated career.

Fig. 5. Poison River, 1988. Wood, cut tin, nails, stones, industrial sealing compound, and enamel on wood; height 48 1⁄2, width 61 1⁄4, depth 2 1⁄2 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

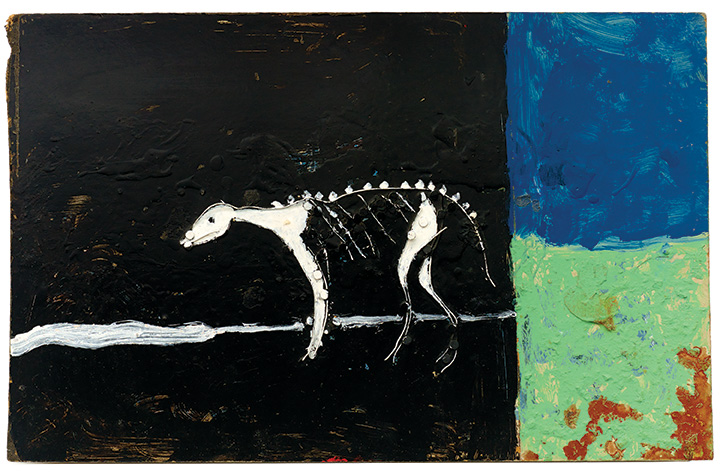

Lockett’s earliest explorations mined religious themes and took shape as mixed-medium paintings rendered on found wood or painted constructions of wood, wire, and metal. These included renditions of Bible stories such as David and Goliath and Daniel in the Lion’s Den as well as interpretations of the Peaceable Kingdom, Revelation, and the Crucifixion (Fig. 4). From the outset, however, Lockett was experimenting with iconographies of his own invention. His Rebirth compositions, for example, presented the skeletal form of a deer against a pitch-black background signifying the grave, its back to the living world delineated in blue and green (Fig. 3). These delicate creatures, “babies” as he termed them, stood as avatars for himself as well as for the more general universe of all vulnerable creatures—humans included. By the end of 1990 Lockett had developed additional themes, each with its own pictorial strategies. The stygian darkness of Smoke-Filled Sky (Fig. 7), depicting the still-glowing ruins of burned-out African-American homes torched by segregationist night riders, and Traps (Fig. 6), where panicked deer and other woodland creatures are ensnared in netting or hobbled by leg traps, built on motifs he would use throughout his body of art. Even as he engaged thematic works in series, he created individual pieces that included reflections on Hiroshima, the Holocaust, and environmental degradation.

Fig. 6. Traps, 1989. Found metal, wire, wood, chain-link fence, and paint; 48 inches square by 3 inches deep. Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, gift of the William S. Arnett Collection and Ackland Fund; Ackland Art Museum photograph.

In 1993 Lockett’s work underwent a profound transformation. He set aside brush and paint, scrap lumber, paint-stiffened cloth, and scavenged twigs and branches and began creating work from found and weathered roofing and siding tin. Feeling his way through the possibilities of the medium, he developed a technique that often began with drawing the outline of the subject on the metal surface and then completing the gure either by fashioning the animals and people out of snipped strips of metal tacked to the ground or punchwork designs hammered through the rusted surface. All of the metal compositions were mounted on found-wood supports that ranged from recycled signage to cast-off shipping pallets.

Fig. 3. Rebirth, 1987. Wire, nails, and enamel on Masonite, 12 by 18 1⁄2 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta, Georgia, William S. Arnett Collection.

Within eighteen months Lockett had reinvented his method by tapping into quilting techniques he learned from Sarah Dial Lockett, the family matriarch. He explained how he hoped his medium and technique in the 1995 Oklahoma series (see Fig. 9) would convey the horror and pain of the bombing: “I didn’t want to offend anybody that was kind of connected to that tragedy, but if I did make a piece I liked it to be some kind of way of expressing about how those people might have felt through that piece.” Each of the eight works consists of “pieced” metal squares and rectangles juxtaposed with a section of metal grillwork. Working with the geometrical shapes and distressed surfaces of the cut tin, Lockett limned an urban landscape with office blocks and the bomb-shorn facade of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. In some later works he combined painting and found metal in compositions that mourned the death of Sarah Dial Lockett (Fig. 13) and Princess Diana (Fig. 12).

The question that remains is how we locate Lockett’s place in histories of American art. Although critics categorized his work with labels, including folk and self-taught, their efforts fell short and wide of the mark. Lockett, like Dial and Lonnie Holley, an artist, musician, and spoken-word performer at the heart of the Birmingham-Bessemer school, simply does not fit easily into iterations of folk that still valorize the naïve and the unlettered. Rather we can see in retrospect that Lockett was a central gure in a school of art defined by work with found material and an abiding interest in historical, political, and spiritual themes. Lockett was very aware of his place in that artistic conversation.

Fig. 4. Sacrifice, 1987. Metal, wire, nails, and enamel on wood; height 28, width 13 1⁄4, depth 1 1⁄2 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

Fig. 7. Smoke-Filled Sky (You Can Burn a Man’s House but Not His Dreams), 1990. Charred wood, industrial sealing compound, and enamel on wood; height 47 3⁄4, width 77, depth 3 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

In 1997, near the end of his life, suffering from HIV/AIDS, and deeply aware of his own mortality, Lockett addressed the camera held by videographer David Seehausen: “I feel like every time I make an artwork I like to kind of like express myself strongly so that person can feel something.” He continued, “I’ve seen the folk art, I’ve stared at it for hours admiring that person for them being able to kind of put something, display a feeling, if it was a sculpture or a piece of artwork where that person can kind of see into that piece and you can feel the same thing they felt.” Reflecting on Lockett’s words, it is clear that he plumbed the wellspring of a folk imaginary in ways that resonate with practices of American artists, such as Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. Like them, he invented his practice and refined his vision in a crucible of everyday things and observations.

Fig. 8. The Beginning, 1993. Nails, tin, and cut found steel on wood; height 42, width 47, depth 2 1⁄2 inches. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

Later in the interview, his last, Lockett returned to the question of his influences, most significantly his cousin the artist Thornton Dial (whom he called “Uncle Buck): “My uncle was…a driving force of my artwork. I told him I wanted to go to art school and he told me I had the best school of all just making artwork or whatever. He was a big influence on my artwork. I mean, he helped me to kind of find out that you could take tin or barbed wire or different small little metals and make things out of them.” Lockett added, “All the pieces that I made are primarily because of him, because he helped me to keep going on even when I couldn’t afford to buy paint, he had paint and would pour me out blue paint, red paint, when I couldn’t really afford paint until I started making some money off of it.”

Fig. 9. Oklahoma (from the Oklahoma series), 1995. Paint, found sheet metal, tin, wire, and nails on wood; 52 inches square by 4 inches deep. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

The interactions between Dial and Lockett extended beyond words of encouragement and the sharing of supplies. The two artists, who lived just doors apart in a family enclave in the Pipe Shop neighborhood in Bessemer, visited regularly, observing each other’s process and acquiring new strategies for their work. Lockett reprised the nature of these exchanges: “The piece Oklahoma, I asked him if he liked it and he said,‘yeah,’ he liked it….I remember one time I made a piece called…Vanishing Territory. I remember when I made it he was standing behind me when I was drawing it, and I never really erased or anything on my painting of the wolves and he was looking surprised at what I was doing, but then I was just amazed at what he was doing, so I was kind of proud of myself that he had some kind of mutual respect for my artwork just like I had for his. So I had [drawn] some deer one time, and he sit behind me and watched me draw the figures out and stuff and be amazed you know that I could do it. But I was just amazed at what he could do.”

Fig. 10. Lockett with Thornton Dial (1928–2016) and Lonnie Holley (1950–) in a photograph by William S. Arnett, January 1997, on a visit to New York City. Souls Grown Deep Foundation Photographic Collection.

The connections and influences shared by Lockett and Dial embraced other makers as well (see Fig. 10). The artist Lonnie Holley spent significant time with Lockett in the 1990s, collecting thrown-away materials that included wire, tree branches, and roofing tin. As Holley recalls, “Me and Ronald was just walking and looking at all this stuff. And I was showing him how some of these things could be used in the forming of his art. So I think that’s really what he locked on to or latched on to and he started using it.” Holley went on, “He was a man of few words, he didn’t say very much. You know he didn’t really explain a lot of his works. But his works was environmental. His works was all about creatures and animals. Entrapment. Or opportunities that were fenced around away from the animals.”

Fig. 11. Untitled (Tribute to Ronald Lockett) by Thornton Dial, 1998. Carpet, rope carpet, clothing, artificial flowers, artificial vegetables, artificial leaves, Splash Zone compound, enamel, and spray paint on canvas on wood; height 48, width 60, depth 5 1⁄2 inches. Collection of Williams S. Arnett.

For Lockett, perceptions of environmental degradation and loss of opportunity were forces that deeply affected humans as well, himself included. Even as Lockett learned from Dial and Holley, he drew on a deep history of artistic production discovered in the quilts pieced by Sarah Dial Lockett and the roses she grew in her dooryard garden. Similarly, he acquired skills from neighbors including Melvin Craver, a builder who lived on the same street.

Fig. 13. Remembering Sarah Lockett, 1997. Found metal, wire, and paint on wood; 48 inches square. Ackland Art Museum, gift of the William S. Arnett Collection and Ackland Fund; Ackland Art Museum photograph.

The Birmingham-Bessemer artists did not constitute a school in an institutional sense or even in the sense that they adhered to a manifesto of enumerated principles. Their school was forged in a continuing practice richly varied in its appearances and extraordinarily coherent in its underpinnings. Certainly, an aesthetic of the “found” stands at the heart of their collective enterprise. They found galaxies of possibility in worn scraps of cloth torn from old work clothes or twisted rebar embedded in ragged concrete or industrial carpet scraps or broken farm tools or any of the countless shards of everyday life deemed trash and without value. They invested their constructions with associations achieved through unexpected juxtapositions where branches become the legs of running deer and swatches of chain-link fencing a cipher for ensnarling nets. Although they rendered powerful and affecting visual statements through their art, they did not see it as “pretty.” “Pretty” captured a kind of art that, as Holley has explained, did not respect the lived experiences encoded in found objects. The art of the Birmingham-Bessemer school could be lyrical, but it was also deeply narrative, drawing on signifying strategies that delivered sharp rebukes to power without exciting its wrath—or envy.

Fig. 12. England’s Rose, 1997. Tin and cut tin, nails, and enamel on wood; 48 1⁄4 inches square by 1 3⁄4 inches deep. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, William S. Arnett Collection.

The Birmingham-Bessemer artists were aware of their connections, even when they had never met. Thus, when Lonnie Holley introduced Thornton Dial to Joe Minter in the years after Lockett’s death, the three artists immediately recognized their common ground and the opportunity to exchange ideas and practices—just as Lockett did with Dial in Pipe Shop or with Holley on their walks together. Holley repudiates the designation “folk” artist and its associations, preferring to describe himself as an American or African-American artist. Dial viewed the label as irrelevant to his work and vision. Lockett, too, never described himself as “folk.” But they did align themselves as a community of sensibility, conversation, and deep purpose. Shortly after Lockett’s death, Dial created two commemorative works. For one, he visited the garage that had served as his young protégé’s studio and peeled up large sections of the paint-encrusted floor. He carried those fragments home to his own workspace and reassembled them into an abstract memorial, Ronnie’s Floor (1998). In the other, a deeply textured mixed-medium painting (Fig. 11), Dial portrayed Lockett in the avatar of the stag, monumentally antlered and lying confident, triumphant and serene, beneath a brilliant blue sky. The buck boldly confronts the viewer across a field of vividly colored owers. This is Lockett’s Eden. There is sorrow in the work—and celebration.

BERNARD L. HERMANis the George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His recent books include Thornton Dial: Thoughts on Paper (2011), and Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett (2016).

Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett is on view at the American Folk Art Museum in New York to September 18; it will then travel to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (October 9, 2016 –January 8, 2017) and the Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (January 27–April 9, 2017). The Souls Grown Deep Foundation Photographic Collection, now housed in the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill, includes numerous unpublished images of Lockett and his art.