This article originally appeared in our September 1964 issue

French architects, painters, and craftsmen in the decorative arts played an important role in the development of the classical style in America during the second and third decodes of the nineteenth century. This is particularly true of a group of cabinetmakers who settled in New York and Philadelphia and included, among others, Michel Bouvier, Joseph Brauwers, Charles Honore Lanuier and his successor John Gruez, and Antoine Gabriel Quervelle. The last of these men has been mentioned on a number of occasions in ANTIQUES and elsewhere but no attempt has been made to reconstruct his career in this country or to assemble a representative group of his furniture. This can now be done, at least in part, thanks to recently found documents and to several hitherto unknown pieces bearing his label, on the basis of which other furniture can be attributed.

Antoine Gabriel Quervelle was born, according to the inscription on his tombstone in Old St. Mary’s Roman Catholic cemetery in Philadelphia, in Paris in 1789. Nothing more is known of his early years. Like Lannuier, he may have belonged to a family of cabinetmakers, for there was a Jean-Claude Quervelle (1731-1778) who worked at Versailles as ébeniste du garde-meuble de la Couronne. Antoine Gabriel received his training during the Napoleonic era and may, like other young Frenchmen, have left France disillusioned after the fall of Bonaparte. The inventory of his household furnishings, at the Philadelphia city hall, filed at the time of his death, lists several engraved portraits of Napoleon, which suggests that Quervelle may have a long-lived admiration for the Emperor.

The young French cabinetmaker was in Philadelphia early in 1817 if not before, for January 30 of that year, in Old St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic church, he married Louise Genevieve Monet, also of Paris, whose father, Pierre, is listed as “machine maker” in the Philadelphia directories of this time. The Quervelles had two sons, Pierre Gabriel and Antoine Louis, born in 1817 and 1826 respectively, both of whom were baptized in Holy Trinity Church on Spruce Street. Mrs. Quervelle died on November 22, 1847, at the age of fifty-four. Her husband, beside whom she lies buried in Old St. Mary’s churchyard, subsequently remarried and had a daughter, Caroline, named for his second wife. He died on July 31, 1856, aged sixty-seven.

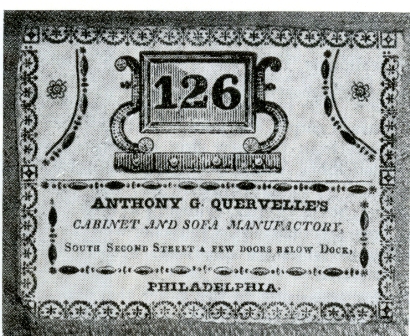

Anthony G. Quervelle, as he was known in Philadelphia, is listed as a cabinetmaker in the city directories from 1820 until his death. He became a United States citizen on September 29, 1823, when he was living and working at Eleventh and Lombard Streets. In 1825 he moved to 126 South Second Street, where he opened his United States Fashionable Cabinet Ware Houseor Cabinet and Sofa Manufactory and where he lived intil 1849, when he is listed at 72 Lombard Street.

On Second Street Quervelle was a neighbor and friend of another French cabinetmaker, Michel Bouvier (see ANTIQUES, February 1962, p. 198), who owed him $1,250 at the time of his death. This was subsequently repaid to Quervelle’s estate. Both Frenchmen competed in the early exhibitions of mechanical arts of the Franklin Institute, founded in 1824, which brought together the leading furniture makers of Philadelphia of the time: Joseph B. Barry, John Graham, John Jameson, John A. Stewart, E. and John Stiles, Robert West, and Charles H. White, as well as the specialists in fancy chairs, Joseph Burden and Alexander and I.H. Leacock, about whom practically nothing is known today.

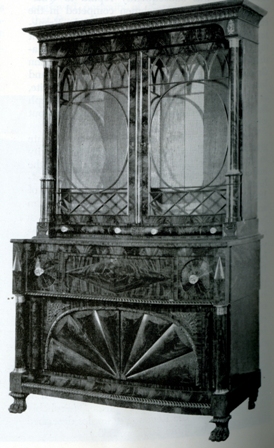

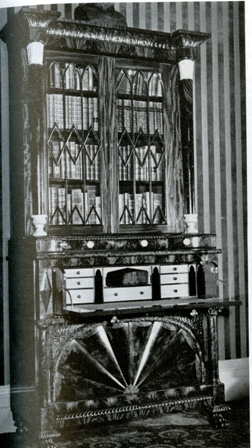

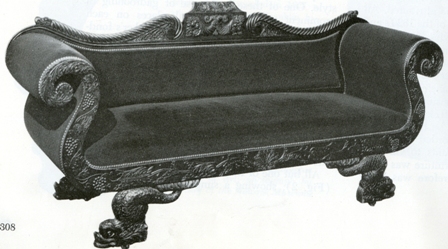

The annual reports of the Franklin Institute give an unparalleled portrayal of taste and activities in the furniture field in the 1820’s and attests the important role that Quervelle played in the exhibitions. At the second, held in the autumn of 1825, he showed two pier tables, which won him an honorable mention. In 1826 he displayed a “sideboard with American marble top” that was awarded a bronze medal. The next year Quervelle earned a silver medal for the best “cabinet book case and secretary.” This piece, now at the Philadelphia Museum, was judged “a splendid piece of furniture from the establishment of this excellent workman,” who according to the census of 1830 employed seven assistants (Bouvier had eleven). In 1828 Quervelle received a premium for the best sofa exhibited. In 1831 he showed a dressing table and a “Ladies Work Table” which were praised along with a dressing table by Joseph Barry, himself a judge, and a “globular” worktable by Bouvier, “the design of which is new, and the workmanship exquisite.” (Probably this last was like the Regency examples described in ANTIQUES for June 1957, p. 553).

In 1829 President Andrew Jackson furnished the East Room of the White House with lemon color wallpaper, black and gold marble mantels, and a frieze of “24 gilded stars, emblematic of the States.” The blue and gold moreen draperies, the Brussels carpet, the mirrors and lamps were purchased from the new firm of Louis Veron of Philadelphia, which between 1828 and 1837 conducted a “Fancy hardware etc. store” at 98 Chestnut Street. Veron, evidently a Frenchman, may have recommended Quervelle, who made a number of tables for the room. Five of these have survived.

It was apparently to this order that the successful cabinetmaker referred when in 1830 he advertised in the United States Gazette that “he had been employed as well by some of the first individuals of the city as by the general government.” He thanked “his friends & the public, for the liberal patronage they have extended to his establishment” and urged them to inspect his “complete assortment of plain and elegantly ornamented Mantel and Cabinet Furniture.” This he had described two years before in the American Daily Advertiser as including “very elegant sideboards, bureau, sofas, dressing tables, wash stands, breakfast and dining tables mahogany and maple bedsteads.” On both occasions he solicited orders from outside the city, stating in 1830 that “orders from any part of the Union will be promptly executed on the most reasonable terms and gratefully received.” He also advertised in Boston.

To prove that Quervelle grew wealthy from his work several writers have quoted a statement, which they attribute to John F. Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia, to the effect that in 1846 he was worth upwards of $75,000, having “made his money by steady industry and strict economy.” Unfortunately no such statement can be found in any edition of Watson’s book. Evidence does exist, however, that Quervelle became a man of substance. When he died intestate in 1856 he owned a number of houses on Pine, Locust, and Lombard Streets, as well as a partnership in the Bristol Iron Works and a parcel of securities. He was a member of the French Benevolent and French Beneficial Societies and a stockholder in the newly founded Philadelphia Academy of Music, which in 1857 was to inaugurate a splendid opera house, still functioning in Philadelphia, designed by another Frenchman, the architect Napoleon LeBrun.

In Spite of what must have been a large production, very little furniture by Quervelle can now be identified. The same situation prevails in relation to the larger establishment of his New York contemporaries, the firm of Joseph Meeks and Sons (ANTIQUES, April 1964, p. 414). Seven labeled Quervelle pieces have been located and through these a few more can be attributed. All are in the grandiose Empire style of the 1820’s and early 1830’s, the period of the winged-paw foot. No example of styles popular in the 1840’s and 1850’s have been found. For these reasons it seems likely that Quervelle, after his initial success in the 1820’s, gradually transferred his interests to real estate and other business activities, as did Bouvier, and also the Meeks brothers of New York. This would seem to be borne out by the drop in Quervelle’s staff recorded in the census of 1840, from seven assistants to three. It is also possible that his later furniture was made by machine processes and therefore was never labeled.

The labeled and documented Quervelle furniture is made almost entirely of mahogany, crisply and authoritatively carved. It all reveals easily recognizable characteristics of a personal style. One of these is the use of gadrooning in prominent molding in several places on each piece. Another is the French cabinetmaker’s fondness for a variety of case and urn forms, often enriched with reeding and gadrooning and used alone or as bases for the shafts of columns. A third distinguishing mark is the red or gold painted molding set around the mirrors at the back of pier tables; a fourth is the use of fan-shape panel of veneer on the front of a desk or the top of a table. A final characteristic is the combining of scrolls, acanthus leaves, and grapevines into a single opulent decorative member.

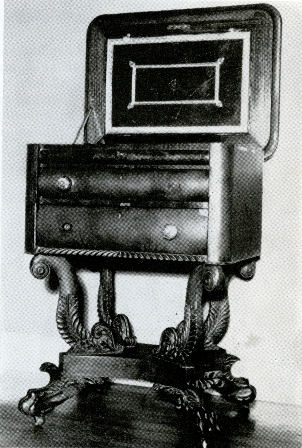

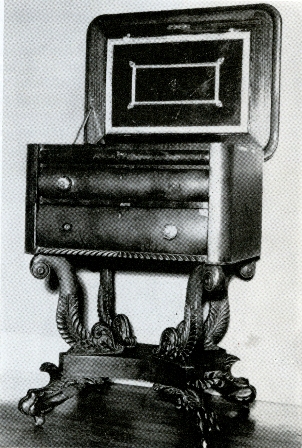

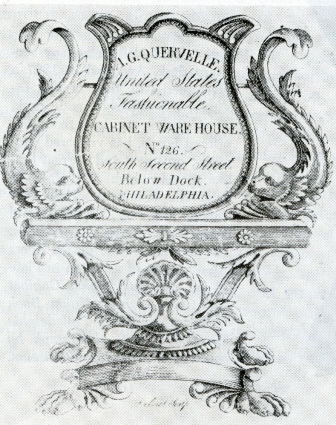

All but one of these pieces have the same label (Fig. 2), showing a simple dressing glass with scrolls supporting the mirror, on which appears the street number of Quervelle’s show on Second Street. One worktable (Fig. 3), however, bears a different label (Fig. 4), displaying a quite fantastically decorated dressing table, inscribed Delmes Sculp. There is no record in Philadelphia directories of this engraver, whose name suggests that he was still another of the French craftsmen who migrated to this country. The label indicates however, that Delmes was not a very accomplished engraver, for the lines are neither fine nor firm and the lettering is badly placed within the frame of the mirror. The label is in fact quite inferior in technique to the worktable on which it is pasted. Since the heavy proportions and scroll feet of this table suggest a dating of 1830 or later, one is tempted to identify it and the dressing table on its label as the two pieces Quervelle displayed at the Franklin Institute exhibition of 1831.

The Delmes label is more useful, however, in attributing to Quervelle a sofa and a pier table ornamented with dolphins comparable to those on the label (Figs. 11,12). Similar dolphins are found on a famous set of English Regency furniture commissioned from William Collins of London by John Fish and bequeathed in 1813 in memory of Lord Nelson to the governor of Greenwich Hospital, much of which is now on display at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. Spouting dolphins were used a few years later on the base of a card table made by Henry Connelly of Philadelphia for Stephen Girard and now at Girard College, and a similar card table (Fig. 9) is owned by Mr. and Mrs. Gustave A. Heckscher. The attributed sofa (Fig. 11), has, in addition to two frilled shells like that on the label, the Quervellian feature of grapevine and fruit mingled with acanthus leaves, while the tails of the dolphin supports seem to end in leafy forms like those on the label and also on the attributed pier table (Fig. 12).

In May 1935 (p.199) ANTIQUES illustrated a card table with the first of Quervelle’s labels, but without disclosing its location. The pedestal base of this table was composed of gadrooned plinth below cylindrical turning resembling the capital and necking of a Doric column with a section of outspread acanthus foliage in the center. The design would seem to authorize the attribution to Quervelle of a tilt-top table (Fig. 13) (a rare form for this period) and a pedestal sewing table with quite similar bases, which belong to a set of furniture made for the Wetherill family of Philadelphia and recently presented to Ainsley Hall in Columbia, South Carolina. The set also includes a sofa and a pair of bow-front bureaus.

The group of fine furniture here illustrated reveals that the shop of Anthony Quervelle, aside from producing excellent carving, turned out impressive pieces in one of the most forceful and attractive personal styles of the late classical period. Most of the furniture was based on fashionable English forms which by 1825 to 1830 were current in American and which Philadelphia, according to the Journal of the Franklin Institute for 1830, varied little from year to year. Thus Quervelle’s pier tables (Figs. 1, 5) go back to an English model of about 1815, of which there is a good example on display in the Regency gallery of the Victoria and Albert Museum. A decade later it had become fashionable to employ a heavier version of the same forms, overlaid with a variety of foliage, as George Smith explains in his Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London, 1826 [1828]). From this pattern book, which appears to have been the most influential source for American furniture of this period, Quervelle could have taken his formula for pier tables, including the grape carving (Plate LXIV) as well as a number of other effective elements, as the Meeks firm of New York City was to do in its broadside of 1833. For example, the eagle head added to the pier table in Figure 5 could have come from Smith’s Plate XCII. Quervelle’s constant use of gadrooning suggests the way Smith employed it (Plates X, XLII, LV, LXXI, LXXIV, CXIX), and several of the Quervelle vase forms recall designs in the English book. In addition, Smith illustrates frilled shells and dolphins (Plate CXV) and outspreading acanthus carving (Plate XVIII).

The way in which Quervelle combined vases with plinths and columnar shafts showed his real originality. He showed it also in his use of geometric ornament and in the grandiose fanlike forms of convex veneering applied to the desks and the attributed piano (Figs. 6,7,8), a heavy Empire version of an Adam device which had enjoyed favor among the Federal cabinetmakers of Philadelphia. Finally, the carving of the lion paw feet, with its unmistakable personal quality, has monumental character that occurs repeatedly throughout this group of furniture.

In preparing this article I received invaluable assistance from Francis James Dallett, director of the Historical Society of Newport, Rhode Island, and Berry B. Tracy, assistant curator of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.