Fig. 1. Pianist and Checker Players by Henri Matisse (1869–1954), 1924. Oil on canvas, 29 by 36 ⅜ inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C., collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Will you please tell Monsieur Matisse the profound impression the exhibition has had upon the painters of this country? I feel it is going to have a very far-reaching effect. —Abby Aldrich Rockefeller1

While the French painter, printmaker, and sculptor Henri Matisse has been universally acclaimed as an influential cultural icon of the twentieth century, Matisse and American Art is the first comprehensive exhibition to examine his profound impact on the development of modern art in America from 1905 to the present. During this period, Matisse’s work has played a more wide-ranging role for both abstract and representational artists than previously understood. His oeuvre has provided a liberating model for their varied explorations of vibrant color, strong fluid lines, and clear compositional structures in the pursuit of artistic self-expression. Featuring paintings, archival objects, sculpture, prints, and works on paper, Matisse and American Art at the Monclair Art Museum in New Jersey juxtaposes nineteen works by Matisse with forty-four works by thirty-four American artists.

Fig. 2. Bellagio Hotel Mural: Still Life with Reclining Nude (Study) by Roy Lichtenstein (1923– 1997), 1997. Cut-andpasted, painted and printed paper on board, 40 ⅛ by 60 ¼ inches. Roy Lichtenstein Foundation Collection, © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue were built on the foundation of several projects, especially co-curator John Cauman’s 2000 PhD dissertation, “Matisse and America, 1905–1933.”2 That work provides a crucial overview of Matisse’s reciprocal relationship with America, and counters the prevailing notion that American art before 1940 played a marginal role in art historical narratives, especially in relation to French art—the standard for modern art. As Cauman observes, Matisse influenced American modernism in its formative stages, and American collectors, critics, connoisseurs, and artists alike played a decisive part in his career and reception here.

Fig. 3. Le Sentier by Alfred H. Maurer (1868 –1932), c. 1908. Oil on gessoed board, 14 ¾ by 18 inches. Collection of Todd Monti.

Elucidating the myriad ways in which Matisse inspired American artists is a complex matter. Not every instance of artistic influence is supported by direct documentary evidence, though in a number of cases newly discovered primary source material illuminates strong connections. Furthermore, the way in which American artists encountered Matisse’s work—whether firsthand, or through reproductions—is significant, as are the effects wrought by their experience of the work of other artists, especially Picasso. The challenges of pinpointing Matisse’s influence also derive from the sheer diversity of his art. Each style had an effect: his early and varied engagement with impressionism; the intense colors and direct, impulsive markings of the fauvist pictures; the monumentality of his decorative panels on the themes of dance and music; his experiments with abstraction; the period of sensuous nudes and light-filled interiors; and the work of his final years, when he resolved what he called “the eternal conflict of drawing and color,” with his inventive cutouts.3

Fig. 4. Apollo in Matisse’s Studio by Max Weber (1881–1961), 1908. Oil on canvas, 23 by 18 inches.

© Estate of Max Weber, courtesy Gerald Peters

Gallery, New York.

It has commonly been asserted that only with the rise of abstract expressionism after 1940 did American art overcome provincialism and finally achieve international significance. It is, therefore, not surprising that most of the exhibitions and publications that preceded Matisse and American Art emphasized Matisse’s influence on postwar and contemporary American artists.4 But beginning in 1908, Matisse developed a large following among American artists, both here and abroad, as a result of their exposure to his work in public exhibitions and private collections and as students at his Académie Matisse, the Paris school he ran from 1908 to 1911. Matisse had also formed close ties with American collectors, especially Gertrude and Leo Stein, the sisters Claribel and Etta Cone, John Quinn, and Dr. Albert C. Barnes. His relationship with America intensified after 1924, when his son Pierre immigrated to America and founded a gallery in New York.

Fig. 5. Four Nudes at the Seashore by Maurice Prendergast (1858– 1924), c. 1910 –1913. Oil on panel, 10 ½ by 13 ¾ inches. Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts, gift of Mrs. Charles Prendergast.

Matisse’s oeuvre suggested a rich variety of possibilities for American artists, who were inspired by its formal elements as well as its subjects and expressive aspects. The exhibition includes two seminal works seen in the artist’s first solo exhibition in America, in 1908 at Alfred Stieglitz’s pioneering art gallery, 291, in New York. One is Nude in a Wood (Fig. 6)—the first Matisse painting to enter an American collection. George F. Of, the modernist painter and framer, lent this bold fauve work to the Armory Show of 1913, which introduced Matisse’s art to the public on a larger scale. While visiting that landmark exhibition, Maurice Prendergast made a sketch with color notations of Matisse’s Nasturtiums with the Painting ‘Dance’ I (1912). In 1915 Matisse had an important solo exhibition at the Montross Gallery in New York. A major exhibition in 1931 at the Museum of Modern Art was followed twenty years later by a retrospective there in 1951.

Fig. 6. Nude in a Wood (Nu dans la forêt; Nu assis dans le bois) by Matisse, 1906. Oil on board mounted on panel, 16 by 12 ¾ inches. Brooklyn Museum, gift of George F. Of, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The American artists featured in Matisse and American Art were selected for the intensity, variety, and quality of their aesthetic engagements with Matisse’s art and philosophy. His transformative inspiration is revealed in their adaptations of his stylistic hallmarks of color, line, and composition, and also in their choice of, and serial approach to, subject matter—still lifes, landscapes, portraits, studio interiors, and nudes. Early twentieth-century explorations of the nude can be seen in the work of Prendergast (Fig. 5) and William Zorach, as well as in that of Matisse’s students Sarah Stein and Max Weber. The latter’s Apollo in Matisse’s Studio (Fig. 4) shows an artist—probably a student —at his easel, dwarfed by a plaster cast of an ancient Greek nude. The stylistic impact of Matisse’s portraits is exemplified by the saturated colors, bold outlines, and simplified forms of Marguerite Zorach’s Connoisseur of 1910 (Fig. 9) and Morton Livingston Schamberg’s Study of a Girl, which was exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show. Works by Arthur Dove, Stuart Davis, Alfred Maurer (Fig. 3), Matisse’s student H. Lyman Saÿen (Fig. 8), and others from 1907 to 1917 likewise reveal American artists’ original and sophisticated adaptations of Matisse’s vibrant palette and harmonious pictorial structures.

Fig. 7. Yellow Odalisque by Matisse, 1937. Oil on canvas, 21 ¾ by 18 ⅛ inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White Collection, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Matisse and American Art also addresses the theme of the window as a metaphor for the dialogue between the interior world of the artist and the external world of reality, as exemplified by Matisse’s Interior at Nice (Room at the Beau Rivage) (1917–1918). Paintings by Milton Avery, Arthur B. Carles, and Hans Hofmann reveal the variety of abstract adaptations of this subject by American artists from 1921 to 1952.

Fig. 8. Still Life by H. Lyman Saÿen (1875– 1918), c. 1912. Oil on canvas, 21 ⅝ by 18 inches. Collection of Mrs. Henry M. Reed.

The exhibition explores in depth Matisse’s pervasive postwar impact, especially his bold, simplified profiles and the vibrant colors of his cutouts, as represented by selections from the Jazz portfolio (see Fig. 11) and Madame de Pompadour (1951). Works by Romare Bearden, Stuart Davis, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Motherwell, and Judy Pfaff exemplify the wide-ranging responses to Matisse’s inventive “drawing with scissors.”

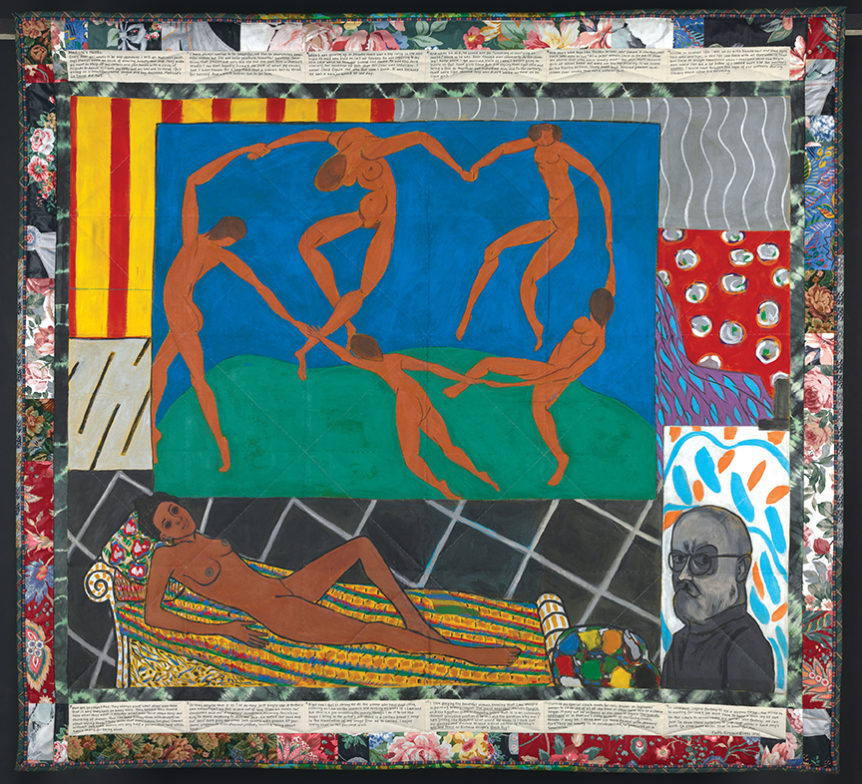

Matisse’s influence on abstract expressionist and color-field painters is represented in works by Motherwell, Richard Diebenkorn, Helen Frankenthaler, and Mark Rothko. Both the large scale and the allover rich red palette of Rothko’s No. 44 (Two Darks in Red) reflect his appreciation of Matisse’s major painting The Red Studio (1911), which was studied by many artists. The exhibition concludes with contemporary works by John Baldessari, Roy Lichtenstein (Fig. 2), Faith Ringgold (Fig 10), Janet Taylor Pickett, Tom Wesselmann, and Andy Warhol, all of whom appropriated and adapted such classic Matisse themes as the dance, the studio, the nude, the portrait, and the goldfish bowl.

Fig. 9. The Connoisseur by Marguerite Thompson Zorach (1887–1968), 1910. Oil on canvas, 22 by 17 ½ inches. Private collection, © The Zorach Collection, LLC.

Whatever medium he chose, Matisse believed that “a work of art must be harmonious in its entirety” and “express almost religious awe towards life.”5 For him, the act of painting was restorative, as he felt “transported into a kind of paradise.”6 Having decided “to discard verisimilitude,” he asserted the significance of “the relation of the object to the artist, to his personality, and his power to arrange his sensations and emotions.”7 Matisse’s complex relationship to aspects of modernism—formalism, decoration, primitivism, classicism, orientalism, abstraction, idealism, and realism—illuminates how he remains a relevant guiding spirit for American artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Fig. 10. Peinture/Nature Morte by Patrick Henry Bruce (1881–1936), 1925–1928. Oil and pencil on canvas, 35 by 45 ¾ inches. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn.

Lichtenstein aptly characterized Matisse, as well as his friend and rival Picasso, as “overwhelming influences on everyone…presences that have to be dealt with.”8 Wesselmann referred to Matisse as “the painter I have most idolized…the most breathtaking painter there is.”9 Believing that an artist “must never be a prisoner…of a style…[and] of success,”10 Matisse has influenced modern and contemporary artists as varied as Frankenthaler and Baldessari, who span formalist and conceptual approaches. With the continuing explosion of access to his work through exhibitions, publications, and the Internet, Matisse’s universally appealing, diverse, and complex oeuvre will no doubt continue to inspire future generations.

Matisse and American Art is on view at the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey from February 5 to June 18. The exhibition is accompanied by a 248-page illustrated catalogue with essays by seventeen scholars.

Fig. 11. Plate II – The Circus from the portfolio Jazz by Matisse, 1947. Six pochoirs on Arches paper, 16 9/16 by 25 ⅝ inches. Herbert Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, gift of Bruce Allyn Eissner and Judith Pick Eissner, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

1 Abby Aldrich Rockefeller to Mme. Duthuit [Matisse’s daughter Marguerite], December 10, 1931, referring to the 1931 Matisse retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Archives Henri Matisse, Paris. 2 John Cauman, “Matisse and America, 1905–1933” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2000). 3 Quoted in John Elderfield, Henri Matisse: A Retrospective (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1992), p. 413. 4 These include Franz Meyer, “Matisse und die Amerikaner,” in Henri Matisse (Kunsthalle Zurich, 1982); Éric de Chassey, La violence décorative: Matisse dans l’art Américain (Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, Paris, 1998); Ils ont regardé Matisse/ Une réception abstraite, États-Unis/Europe, 1948–1968 (Musée Départemental Matisse du Cateau-Cambrésis, 2009); Bonjour Monsieur Matisse! Rencontre(s) (Musée d’Art Modern et d’Art Contemporain, Nice, 2013); Bruce Donald Grenville, “Henri Matisse in America, 1900–1955: A Study of the Dissemination of His Art and Ideas in the United States with Particular Reference to His Influence on Abstract Expressionist Painting in New York” (master’s thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, 1983); and Susan Shawver Leonard, “The Influence of Henri Matisse in the Art of Richard Diebenkorn, Ellsworth Kelly, and Joan Mitchell” (master’s thesis, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1990). John O’Brian’s The American Reception of Matisse (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999) is a useful compilation pertaining to Matisse’s evolving reputation during his own lifetime. The traveling exhibition After Matisse (1986–1988, Independent Curators International) provided the closest model for Matisse and American Art by including the modernists Milton Avery and Hans Hofmann and contemporary artists of the 1980s—Helen Frankenthaler, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Kushner, Sherrie Levine, Miriam Schapiro, and others. A landmark event in the appreciation of Matisse was John Elderfield’s retrospective that opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1992, which, as the largest and most comprehensive exhibition, attracted record crowds, including artists such as Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and Chuck Close. 5 Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter, 1908,” in Jack Flam, Matisse on Art (E. P. Dutton, New York, 1978), pp. 36–38. 6 Matisse’s reference to his first encounter with making art is quoted in Elderfield, Henri Matisse, p. 23. 7 Henri Matisse, “On Modernism and Tradition, 1935,” in Flam, Matisse on Art, p. 73. 8 “Eight Statements,” interviews by Jean-Claude Lebensztejn,” Art in America, vol. 63 (July/ August 1975), p. 69. 9 Ibid, p. 70. 10 Henri Matisse, “Jazz, 1947,” in Flam, Matisse on Art, p. 113.

Fig. 12. Matisse’s Model, no. 5 from the series The French Collection Part I by Faith Ringgold (1930–), 1991. Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, and ink, 73 by 79 ½ inches. Baltimore Museum of Art, Frederick R. Weisman Contemporary Art Acquisitions Endowment, © Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

GAIL STAVITSKY is the chief curator of the Montclair Art Museum, where she has organized numerous exhibitions and served as a primary author for several catalogues, including Cézanne and American Modernism (2009) and The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913 (2013).