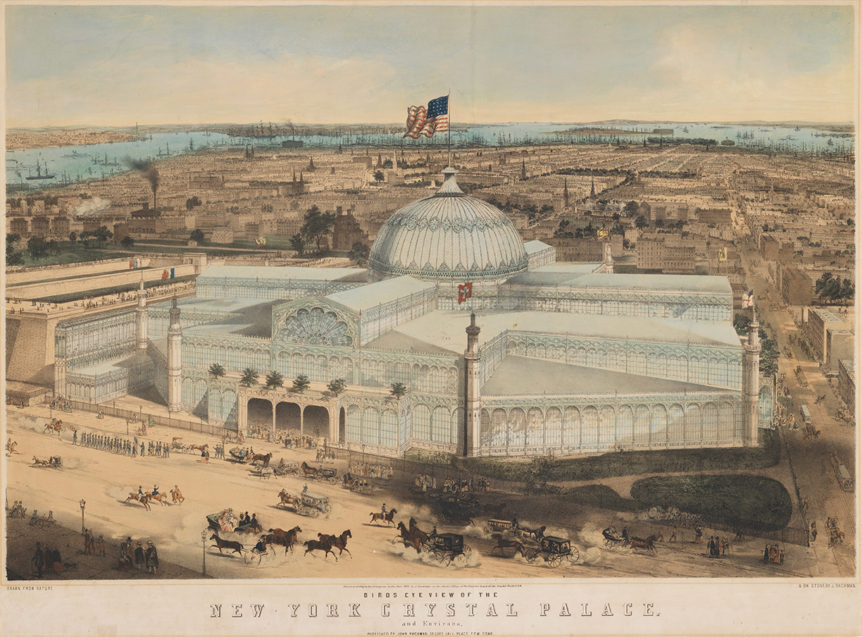

Fig. 1. Bird’s Eye View of the New York Crystal Palace and Environs by John Bachmann (active 1849–1885), 1853. Hand-colored lithograph, 21 by 31 ⅗ inches. “Our exhibition explores the Crystal Palace itself as a phenomenon: how it reflected and affected artistic and cultural sensibilities in the booming mid-nineteenth-century metropolis of New York,” says Marianne Lamonaca, chief curator of the Bard Graduate Center Gallery. Museum of the City of New York, J. Clarence Davies Collection, gift of J. Clarence Davies.

In 1853, when Americans read Paradise Lost more avidly than they do today, visitors to New York’s Crystal Palace would have recalled the lines, “Anon out of the earth a fabric huge/Rose like an exhalation.” Within a matter of a few months, a structure that rivaled in size Saint Peter’s in Rome, then the largest church in Christendom, sprang up along Manhattan’s still sparsely developed grid, in the far north of what was then New York City. Occupying present-day Bryant Park between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, from Fortieth to Forty-Second Streets, this phantom palace, the subject of a new exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center, was in all likelihood the largest man-made object those visitors would ever see. The main rival for that honor until then had been the Croton Reservoir directly to the east, on land now occupied by the New York Public Library on the eastern edge of Bryant Park.

Fig. 2. Medal for the Crystal Palace exhibition, 1853, reverse designed by Anthony C. Paquet (1814–1882). White metal; diameter 2 inches. American Numismatic Society, New York.

It must have been hard for those visitors to imagine that one species, let alone one city, could have brought forth two buildings as different as these. The Croton Reservoir was Egyptian in style and pharaonic in scale. The main source of water for an expanding city, from its inauguration in 1842 to its demolition half a century later, the reservoir rose higher than most of the surrounding buildings and its granite bastions seemed able—should the need arise—to withstand a Saracen assault. By contrast, the neighboring Crystal Palace was a fragile confection of metal and glass, so immaterial, like some celestial vision in a Thomas Cole landscape, that visitors could only marvel that it remained standing at all. The ever-effervescing Walt Whitman came all the way from Brooklyn to have a look and was moved to describe “a Palace,/Loftier, fairer, ampler than any yet,/Earth’s modern Wonder, History’s Seven outstripping,/High rising tier on tier, with glass and iron facades.”

Fig. 3. New York Crystal Palace by Victor Prevost (1820–1881), c. 1853–1854. Salt print photograph, 35 ½ by 60 ¼ inches. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York.

The Crystal Palace was the creation of George Carstensen, a Dane, in collaboration with the German architect Charles Gildemeister. Inspired by Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in London, which had opened in 1851, and contemporary with Munich’s somewhat similar Glaspalast, New York’s interpretation was a miracle of cast iron and cast plate glass, a process invented by James Hartley in 1848 that, for the first time, made it possible to create large-scale buildings covered in glass. Some ten thousand glass panes were deployed across the expansive surface of the structure.

Fig. 4. Interior view of south nave of the Crystal Palace, 1854. Daguerreotype. “One of the themes of our show is new technology,” Lamonaca says. “Photography was in its infancy in 1853. This is one of the only existing photographic images of the interior of the Crystal Palace.” New-York Historical Society.

But the three-story Manhattan building looked very different from its congeners in London and Munich. Carstensen, who is most famous for designing Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, had grown up in the Middle East, and the orientalist element that was so prominent in Victorian taste was very much present in his Crystal Palace. It was an eight-sided building whose central dome, one hundred feet across and 123 feet high, was plausibly described as “the largest dome in the Western World,” recalling the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul. Its main entrances were flanked by towers resembling minarets. At the same time, a Greek-cross layout with four huge naves looked decidedly ecclesiastical, an impression strengthened by the rose-window lunettes above each entrance and by the articulation of the interior walls into arcade, gallery, and clerestory. In addition, thirty-two stained-glass windows graced the dome, which was held aloft seventy-one feet above the floor on two dozen cast-iron columns.

Fig. 5. A Panoramic Representation of the Interior of the Crystal Palace, New York by Frederick J. Pilliner (c. 1827–1861) from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, February 4, 1854. Wood engraving on newsprint, 16 by 22 inches. Private collection.

But if the superficial trappings seemed churchlike, the Crystal Palace celebrated a very new and different religion that was decidedly secular and that enshrined the principles of consumerism and the European Enlightenment, for the building had been created to house a single event, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. This was but one in a long series of international exhibitions that had started in 1798 with the Exposition publique des produits de l’industrie française, located on the Champ de Mars in Paris; it would eventually inspire everything from the Great Exhibition of 1851, in London’s Crystal Palace, to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, for which the Eiffel Tower was built, as well as the New York World’s Fairs of 1939 and 1964. And like all the other exhibitions in that storied series, it was to be an unrestrained celebration of industrial progress and of humanity’s triumphal march into the future.

Fig. 6. Pitcher designed by John Chandler Moore (active 1832–1844), retailed by Ball, Tompkins & Black, 1834–1851. Silver; height 16 ⅜ inches. “A section of the exhibition addresses taste-making in America in this period,” Lamonaca says. “This silver pitcher is of the same form and decoration as a celebrated tea service produced in ‘California gold’ by Ball, Black & Co. that was shown at both the London Crystal Palace of 1851 and the New York Crystal Palace of 1853.” Museum of the City of New York.

The great spectacle opened on July 14, 1853, with President Franklin Pierce in attendance, as well as his secretary of war, Jefferson Davis. In the era before department stores and supermarkets and, of course before the Internet, the fair’s vertiginous plurality of goods and displays must have beggared all description. Some Europeans might have seen similar exhibitions, but this was the first ever to reach America. “Nothing like it in shape, material, or effect, has been presented to us,” wrote Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune. That in itself was an impressive milestone for the nation, but even more so for the city of New York, which was only beginning to establish its supremacy over Boston and Philadelphia.

Fig. 7. Soda water bottle, Union Glass Works, Philadelphia, c. 1850–1860. Moldblown glass; height 7 ⅛ inches. “The soda water bottle—with an image of the Crystal Palace on its side—speaks to the early blossoming of consumer culture,” Lamonaca says. “Manufacturers and retailers saw the Crystal Palace as such a significant thing that they wanted to connect themselves to it.” Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. John R. Graham Jr. in memory of Louise Wood Tillman.

No item was too big or small, too humble or exalted, to merit inclusion. Threshing machines and prairie ploughs, bonnets, etched doilies and Honiton lace, beehives, gingham looms, and shoe-pegging machines were all set up for the edification of the American public and international visitors. It was here as well that Elisha Otis, after whom the Otis Elevator Company is named, demonstrated the first free-fall safety device when, to the gasps of onlookers, an axe-wielding assistant cut the rope that suspended the elevator platform on which Otis stood: it lurched downward two feet before coming, astoundingly, to a halt.

Fig. 8. Sugar bowl with cover, Brooklyn Flint Glass Works, cut decoration by Joseph Stouvenel and Company, c. 1851–1857. Colorless lead glass, mold-blown, applied, machine cutting; height 9 ⅔ inches. “A central theme of our show is to explore the way immigrant artisans and laborers helped transform American manufacturing and tastes,” Lamonaca notes. “Stouvenel was born and trained in Baccarat, France, then brought his talents and techniques to New York to create works like this beautiful sculpture for the table.” Corning Museum of Glass, purchased with the assistance of the Karl and Anna Koepke Endowment Fund.

But for all the marvels of industrial progress, art was hardly neglected. “The great utility of the Crystal Palace,” Greeley wrote, “consists in its forming a standard of Art, and an exchange for testing the values of Industry.” One of the stars of the show was American sculptor Hiram Powers, who, Greeley wrote, “is absolutely unequalled in the perfection with which he reproduces nature. . . . No artist, since Greek sculpture was at its climax, has so given us the convolutions and rounded swell of the muscles.”

As regards the paintings on view, however, the writer Richard C. Williams had a generally more depreciative assessment, and his discussion provides an interesting window into the artistic tastes of the American public at this primitive moment in their evolution. One picture “found at the point of exit from the gallery,” he wrote, “is claimed to be a genuine Carlo Dolci, and will, of course, be an object of great interest to everyone. Of the other reputed originals from the great masters of another age there is a Guido Reni [and] an exceedingly doubtful, if not impossible, Murillo.”

Whatever the ultimate consequence of the art on display, the Crystal Palace was a great success, with more than a million visitors in the five years that it stood. And many more would have come, were it not for the fact that, at 5:10 on the afternoon of October 5, 1858, a fire broke out in a lumber room near the Forty-Second Street entrance, while two thousand visitors were touring the galleries. Although they all got out safely, within twelve minutes of the first reported flames the great dome had come crashing down, and a mere nine minutes after that, the entire Crystal Palace, with most of its contents, had vanished “like an exhalation.”

Fig. 9. New York, 1855. From the Latting Observatory by William Wellstood (1819–1900), printed by Smith, Fern, and Company. Engraving, 29 ⅜ by 46 ⅛ inches. New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Miriam and Ira D.Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

The Crystal Palace of London and the Glaspalast of Munich were likewise destined to end in fire, but in the 1930s, some eighty years after they had opened. By contrast, America’s Crystal Palace, both in its insistence on material progress and in the very evanescence of its material form, could stand as a potent symbol of the modern world and of that most essentially modern city, New York, in its ceaseless abolition of the past for the sake of its future.

Fig. 10. Window shade, New York Crystal Palace, 1853. Machine printed on continuous paper, 60 by 35 ¼ inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, purchase through gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt / Art Resource, NY.

New York Crystal Palace 1853 is on view at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in New York from March 24 to July 30.