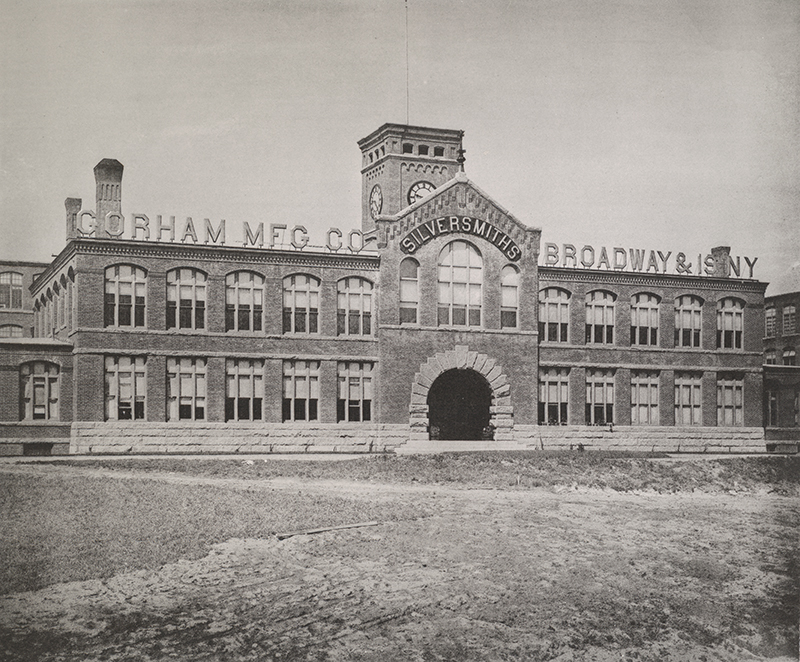

What began as a small shop in the heart of Providence, Rhode Island, boldly rose to become the largest silver manufactory in the world. The company founded in 1831 by Jabez Gorham has, over the decades, created everything from monumental commissioned presentation pieces to functional elegant wares for the country’s dining rooms, all the while responding to and shaping each era’s notion of how to celebrate, feast, socialize, honor, and simply enjoy the everyday in style.

Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance 1850–1970, opening this spring at the museum of the Rhode Island School of Design, charts 120 years of the firm’s output during a period when its industry, artistry, innovation, and technology put uniquely American design on the international stage. The exhibition casts new light on the legacy of this distinctive company, exploring its significance within industrial, social, aesthetic, manufacturing, and marketing contexts. The exceptional silver and mixed-metal wares on view are drawn mainly from RISD’s collection of Gorham silver, the largest of its kind, with the addition of significant loans from collegial institutions and private collections.

The story told begins with Gorham’s transition from its early handmade small wares to its first forays into complex hollowware vessels in the 1850s, and the introduction of mechanization into the manufacturing process. What Jabez Gorham had started, his son, John, spurred to exponential advancement with the introduction of the first steam-powered drop press specifically designed for the production of silver.

The height of Gorham’s production in the second half of the nineteenth century coincided with substantial changes in American social customs and dining etiquette, new culinary developments and trends, and the ongoing association of silver as a gift for celebratory events and the protocol of presentation wares. Gorham not only satisfied its customers’ needs and requests, but also influenced social and cultural history. The refinement of dining practices during the Gilded Age is reflected in the Furber service of 816 pieces, Gorham’s largest commission ever. Made between 1866 and 1880 and fashioned to serve twenty-four guests—the centerpiece and fruit knives and forks are shown below—it is now part of RISD’s collection.

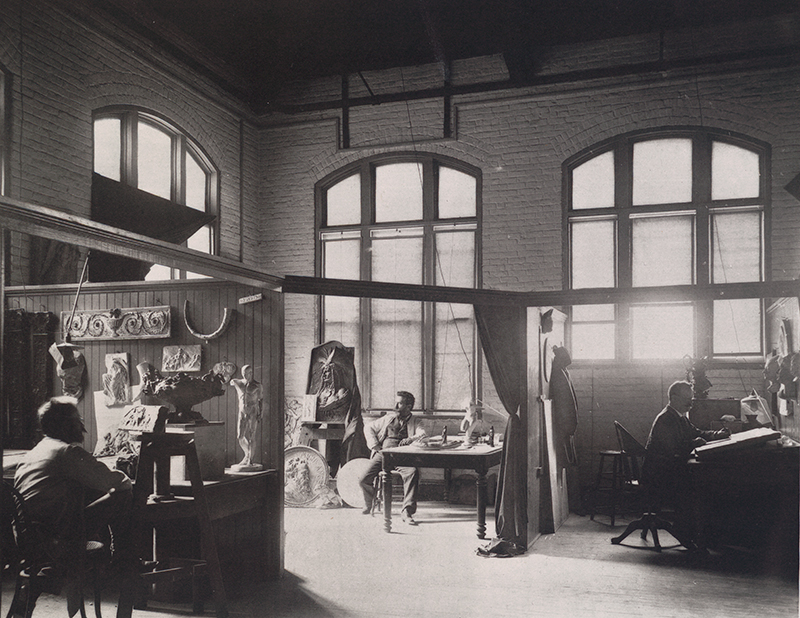

The form and ornamentation of each piece of Gorham silver began in the design department, which held the firm’s design library. An extensive collection of volumes and folios dating from the fifteenth century to the twentieth, the library represented a global array of art and design references and inspirations. The path from a conceptual idea in the mind of a Gorham designer to a fully realized three-dimensional object can be followed through the paper trail of each item’s manufacturing journey. Every design was numbered with an object code and other data. A series of design drawings mapped out the development of a piece, with changes, calculations, parts numbers, material identification, and instructions all noted. Finished Gorham silver wares found their way to the company’s showrooms across the country and to trade fairs around the world. Gorham also produced annual catalogues and countless promotional advertisements.

Throughout the Gorham Manufacturing Company’s existence, a dual respect for what came before and what was possible for the future was fundamental to its development of, and dominance in, the silver industry. The firm’s processes, from administrative management and logistical organization to its creative development and manufacturing methods, were recognized as bringing “the inheritance of an older and richer world to the quick and fertile genius of the new . . . which gives a capital advantage to the American system of business.” Gorham was the epitome of a manufactory—a site where marketable and useful merchandise was produced through both human and machine labor. What the word manufactory often obscures, however, is that it is not “an easy thing to make a design which shall be at once delightful to the eye and convenient to the hand,” as Harper’s magazine noted in an 1868 article on Gorham. “No talent is rarer than this, and without it all the mechanical skill, the perfect integrity, and the courageous enterprise of the Company would not have sufficed to rear so vast . . . an establishment.”

The story told begins with Gorham’s transition from handmade small wares to their first forays into complex hollowware vessels in the 1850s, and the introduction of mechanization into the manufacturing process. What Jabez Gorham had started, his son, John Gorham, spurred to exponential advancement with the introduction of the first steam-powered drop press specifically designed for the production of silver. The latter half of the nineteenth century was a time of substantial transformations in American social customs and dining etiquette, as well as culinary developments and trends, and the period established silver as a traditional gift for celebratory events and the protocol of presentation wares. Gorham not only satisfied their customers’ needs and requests, but also influenced social and cultural histories. The refinement of dining practices during Gilded Age, for example, is reflected in the Furber service of 816 pieces, Gorham’s largest commission ever. Made between 1866-1880 and fashioned to serve twenty-four guests—the centerpiece and fruit knives and forks are shown below—it is now part of RISD’s collection.

The ornamentation and form of each pieces of silver began in the Design Department, which held Gorham’s design library. An extensive collection of volumes and folios dating from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries, it represents a global array of art and design references and inspirations. The path from a conceptual idea in the mind of a Gorham designer to a fully realized three-dimensional object can be followed through the paper trail of each item’s manufacturing journey. Every design was numbered with an object code and other data. A series of design drawings mapped out the development of a piece of Gorham silver, with changes, calculations, parts numbers, material identification, and instructions all noted. Finished Gorham silver wares found their way to the company’s showrooms across the country and to trade fairs around the globe. Gorham produced annual catalogues and countless promotional advertisements.

Throughout the Gorham Manufacturing Company’s existence, a dual respect for what came before and what was possible for the future was the foundation for their development in and dominance of the silver industry. Their processes, ranging from administrative management and logistical organization to creative development and manufacturing methods, were recognized as bringing “the inheritance of an older and richer world to the quick and fertile genius of the new…which gives a capital advantage to the American system of business.” Gorham was the epitome of a manufactory—a site where marketable and useful merchandise was produced through human labor and machines. What the word manufactory often obscures, however, is that it “is not an easy thing to make a design which shall be at once delightful to the eye and convenient to the hand,” as Harper’s magazine noted in an 1868 article on Gorham. “[N]o talent is rarer than this, and without it, all the mechanical skill, the perfect integrity, and the courageous enterprise of the Company would not have sufficed to rear so vast . . . an establishment.”

As explorers made tracks within and beyond the boundaries of the United States, artists followed, with new discoveries making their way into contemporary design. Silver icebergs, polar bears, and caribou adorn this ice bowl, one of several versions made by the Gorham Manufacturing Company beginning in the late 1860s. Its iconography relates not only to expeditions, but also reflects the expansion of America’s borders, including the 1867 purchase of Alaska from Russia. Back home, Bostonian Frederic Tudor, known as the Ice King, had perfected the process of harvesting New England ice and shipping it worldwide. Encircled by icicles and accompanied by tongs formed as a rope-entwined harpoon, this bowl made provided an impressive presentation.

Exemplifying in majestic form the showy centerpieces popular in the late nineteenth century, this epergne with plateau is the grandest and most complex piece of the Furber service. Designed by Thomas Pairpoint, it deftly combines popular Neoclassical motifs, including the plateau’s scaled adaptation of the Greek Parthenon frieze, with American iconography. Dressed in a silver gown embedded with gilded stars, Columbia, the personification of the United States, stands on a globe and holds a gilded garland aloft, assisted by a pair of putti. Adorned with golden hummingbirds, the shell-shaped bowls were for flowers. The oblong bowls, mounted with sterling repoussé plaques featuring allegorical representations of Love and Contentment, were filled with fruit.

In 1881, Gorham introduced a line of copper-bodied wares in a wide range of color tones that featured mixed-metal appliqués and decorative borders. These pieces were often finished with a rich, deep reddish-brown glossy patina, referred to as “red copper.” In 1882, the Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review described the line: “Copper predominates, . . . the colors are dark warm reds of finest polish, mellowing into yellowish browns; scales and shadings . . . wine tinted. . . in warmest red tints, [with] . . . the highest polish.”

This service is an elaborate example of the company’s Oriental East Indian pattern, a blend of Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Islamic, and Greco-Roman aesthetics. Further compounding the decorative scheme, each of the six pieces is individualized in its ornament, yet all come together as a harmonious whole. This service is a masterpiece of silversmithing, with relief decorations requiring hundreds of hours of hand-worked chasing. Gorham’s chasers were among the most skilled silversmiths in the field, commanding the highest pay for years of training and experience. In 1862, the Chasing Room provided 70 feet of workbenches and fourteen stools at which the chasers sat “in rows, each with a piece of plate under treatment.” With the opening of their new Elmwood facility, nearly 100 chasers sat at workbenches “where the full light from long windows fell upon their work.”

Rhode Island, known as the Ocean State, was an important source of Gorham’s inspiration. Sometimes taken from specimens, cast silver element shifted from serving as ornamentation decorating hollowware vessels to becoming the elements that formed the object themselves. In 1884, Gorham launched the Narragansett line, its name originating from the Native American tribe that occupies the coast of Rhode Island and eponymous with the inlet on the north side of the Rhode Island Sound, Narragansett Bay. Looking as if they were plucked from the ocean, the servers are encrusted with shells, crabs, sand, and strands of seaweed tangled with fish. The spoon’s gilded oyster shell-shaped bowl appears to be awash with the receding tide that has left behind a small shell surrounded by grains of sand.

Raised by hand rather than spun on lathe, a series of important vessels made in the mid-1880s exemplifies not only the talents of Gorham’s chasers but their ability to transform these age-old skills into innovative creations. This lidded tureen appears to gyrate with the strong diagonals of waves that encompass its circular form, virtually spinning out of control as high-relief fish leap and dive into the waves. The handles resembling knobby branches of coral, on which two crabs sit, and the sea-urchin finial exemplifies the company’s talent for extreme realism in silver.

In the early 1890s, electro-deposition on glass was hailed as the most modern of the methods used by Gorham to join glass and silver, as it employed an “electric process, the genius of Electricity obediently doing and undoing according to the will of his new-found master, Man!” However, it was women who carried out the steps to produce these fashionable wares. The glass was coated with a metallic-based flux such as silver nitrate, which attracted the silver in an electroplating bath, completely covering the object with silver. The design was painted onto the vessel with resist varnish, and then the object was placed in a bath, reversing the electrical process. As the silver dissolved on areas unprotected by the varnish, the “sparkle of the glass through the net-work of silvery scroll” was revealed.

Commanding as much attention now as when they debuted at the 1904 World’s Fair, this writing table and chair were conceived as showstoppers in a crowd of stunning objects made by Gorham’s competitors. More than 10,000 hours of labor, 47 pounds of silver, and a panoply of exotic materials make up this unique set, which deftly melds sinuous Art Nouveau floral and figural motifs, 18th-century French Rococo forms, and traditional Hispano-Moresque designs. Intricately wrought symbolism—seen in the daytime poppies and the night owl below the mirror and the decoration of the legs, each representing one of the four seasons with female masks surrounded by lilies, roses, chrysanthemums, and pine cones—attests to the complexity of Gorham’s design, which brought them the Grand Prize in silversmithing.

Hired to infuse modern style into Gorham’s designs, the accomplished Danish émigré Erik Magnussen arrived in Providence from Copenhagen in 1925. The company emphasized Magnussen’s celebrity, assigning a distinct series of model numbers to the works that were stamped with the designer’s individual makers mark. Magnussen created his most radical piece. the Cubic Service, with gleaming triangular facets of sterling, gold, and dark-patinated silver that echoed the fragmented objects depicted in contemporary Cubist works. Creating an immediate sensation when it was displayed in the company’s Fifth Avenue New York showroom, the service was dubbed the “Lights and Shadows of Manhattan.” The service’s forms read like a series of angular buildings rising from the ground, suggesting the American city and its soaring skyscrapers, along with the emergence of industrial design and its Modern, streamlined image.

The handles of the Furber fruit knives and forks derives from kozuka, the handles of small Japanese knives known as kogatana, an important part of Japanese sword fittings. They are made of cast bronze or silver with gilded decorations of mythological figures, birds, marine life, horses, military furnishings, masks, deer, bulls, and flora, while the tines and blades are engraved with aesthetic movement floral and textiles patterns.

Hired by Gorham in 1958, designer Donald H. Colflesh ushered in the next decades, creating futuristic forms during a transitional period that focused on space travel, nuclear power, atomic bombs, and high-tech materials. The dramatic upward thrusting lines of the Circa ’70 tea and coffee service suggest a launch into the stratosphere, alluding to the space age by referencing a date a dozen years in advance in the pattern’s name. Although the service’s forms indicate the Modern era, they are countered by use of the decidedly traditional materials silver and ebony, as indicated on a design drawing. A modern material would enter the service in 1963, with the addition of a silver tray with a Formica center.

These flatware design samples in Gorham’s Mythologique pattern combine intricate detailing wrought from hours of modeling by hand with the evidence of a drop press’s mechanized brute force. They also testify to the desire nineteenth-century Americans felt for designs derived from the past as they simultaneously embraced the industrial processes that would guarantee the country’s future. The polished refinement of Antoine Heller’s twenty-four handle designs, each depicting different mythological figures and scenes, contrasts with the utensils’ unfinished lower sections—note the untrimmed excess metal left between the fork tines.

Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance 1850–1970 will be on view at the RISD Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence from May 3 to December 1. It will then travel to the Cincinnati Art Museum and to the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 2020. This article is adapted from the accompanying book of the same title, to be published by Rizzoli in May.

Elizabeth A. Williams is the David and Peggy Rockefeller Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the RISD Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design. She is the curator of the exhibition Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance1850–1970 as well as editor of and contributing author to the accompanying book.

1 William C. Conant, “The Silver Age,” Scribner’s Monthly, vol. 9, no. 2 (December 1874), p. 202. 2 “Silver and Silver Plate,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 37, no. 220 (September 1868), p. 433. 3 “The Modus-Operandi of Electro-Plating in Silver,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 1, 1892. 4Julia Osgood, Silversmiths’ Work in the Liberal Arts Building of the Columbian Exposition (Providence: Gorham Manufacturing Company, 1894), p. 13. 5 Gorham Manufacturing Company, Woman’s Work at the Gorham Manufacturing Company (Providence: Gorham Manufacturing Company, 1892), n.p.