New York City’s Central Park was a prescient masterstroke of urban planning in the nineteenth century. Completed in 1874, the green space created by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux flowers on, vital in every sense, as a living work of art. But what’s generally overlooked is that the 141 statues and monuments that stand on Central Park’s 843 acres make it, as the city’s parks commissioner Mitchell J. Silver says: “the world’s largest outdoor art museum.”

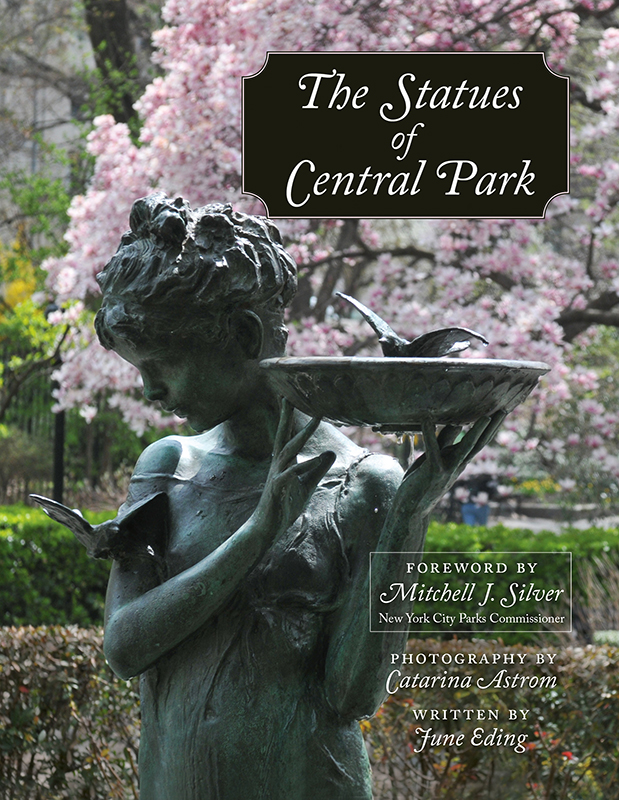

Untermyer Fountain (Three Dancing Maidens) by Walter Schott, designed 1903, this version installed 1947, is located on the park’s east side at 105th Street. All photographs by Catarina Astrom, courtesy of Hatherleigh Press.

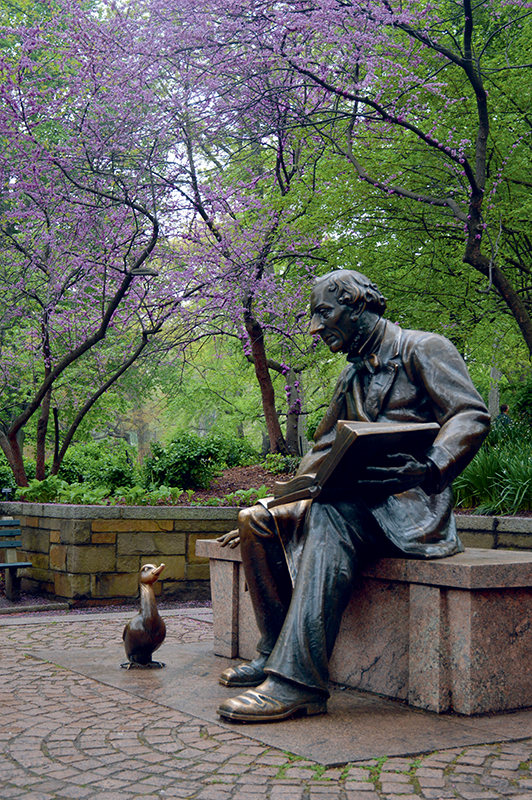

Silver’s comment comes in his foreword to The Statues of Central Park, a new, useful, and handsome little volume that serves to inform us about some of the park’s lesser-known sculptures. Certainly much of the statuary in Central Park does not lack for attention. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s magnificent equestrian monument to William Tecumseh Sherman at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-ninth Street was a traffic-stopper even before it was first re-gilded in 1990. Some of the statues in the park are even beloved by New Yorkers—as anyone will attest who has seen kids clambering happily over the statue of storyteller Hans Christian Andersen or the Alice in Wonderland sculptural group not far away, near the Conservatory Water.

Yet many engaging and distinguished works get little love and recognition. As the new book reminds us, there is, for example, another wonderful sculpture depicting Lewis Carroll’s creations in Through the Looking Glass: the stone fountain—now located at the center of a playground—that memorializes Sophie Loeb, a tireless advocate for children’s welfare in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Loeb fountain was sculpted by Frederick George Richard Roth, who also made Central Park’s statue in honor of Balto and the other sled dogs who in 1925 delivered medicinal serum through a blinding blizzard to the victims of a diphtheria epidemic in Nome, Alaska.

The Statues of Central Park by June Eding, with a foreword by Mitchell J. Silver, and photographs by Catarina Astrom. (Hatherleigh Press, 2018). 192 pp., color and b/w illus.

A playground figures in another great work of art in the park, near Eighty-fifth Street on Fifth Avenue. Visitors hurrying to the Metropolitan Museum may pass by without noticing the wonderful gate to the Ancient Playground—actually one of the newer such areas, so named because its climbing features are modeled on Egyptian architecture—which feature characters from five of Aesop’s fables sculpted by Paul Manship.

Hans Christian Andersen by Georg John Lober, installed in 1956, sits on the park’s east side near 74th Street.

The Statues of Central Park offers an array of interesting historical details. Among them: the oldest sculpture in the park, cast in 1850 in Paris, is also its most disconcerting. Eagles and Prey depicts a pair of the birds flapping their wings as they sink their talons into a dying goat. For all the gore, the sculpture by Christophe Fratin is remarkable in its realism, down to the barbs of the eagles’ feathers.

The book also sheds light on Fitz-Greene Halleck, whose statue—on the Literary Walk in the company of monuments to the likes of Robert Burns and Walter Scott—bewilders most who encounter it. Halleck, it turns out, was a poet and noted wit in early nineteenth-century New York. Though his statue was unveiled by no less than President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877, Halleck’s humor has not aged well. The book notes a monument to another person mostly forgotten but one well worth remembering: William T. Stead. A sculpted plaque near Ninety-first and Fifth honors the Briton, a pioneering investigative journalist and social reformer. He died aboard the Titanic, last seen by survivors helping women and children board the lifeboats.

The Osborn Gates on the park’s east side at 85th Street were sculpted by Paul Manship and installed in 1953.

Capably written by June Eding and with fine and, in instances, lovely photography by Catarina Astrom, The Statues of Central Park makes an excellent souvenir of—again to quote Silver—the “amazing collection of permanent art dispersed throughout New York City’s and the world’s most iconic park.”