Fig. 1a. HMS Resolution and Adventure (Banks/Cook) Medal by Matthew Boulton,1772. Silver, diameter 1 5/8 inches. On the obverse: Bust of George III with the inscription “GEORGE• III• KING• OF• GR• BRITAIN• FRANCE• AND• IRELAND• ETC•”. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Fig. 1b. Reverse of Fig 1a. Starboard-quarter view of Resolution (left) and port-quarter view of Adventure (right), with the inscription “RESOLVTIONADVENTVRE•/SAILED•FROM•ENGLAND/ MARCH•MDCCLXXII.” National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

European explorers of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries often introduced novel items to the indigenous people they contacted during their travels. Utilitarian objects such as nails, needles, fishhooks, and knives were particularly popular gifts because they were difficult for nonindustrial societies to manufacture for themselves. Personal items such as mirrors, beads, buttons, and bolts of cloth were readily accepted by native people for the same reasons. Far less common were the medals created to serve as gifts of diplomacy for native people. They document that short period when different cultures first came into contact and treated each other with curiosity, civility, and, at least for a while, a modicum of respect.

Fig. 2. Chief from Fort William by Paul Kane (1810–1871), 1849–1856. Oil on canvas, 30 ½ by 25 inches. The chief, an Ojibway named Maydoc-game-kinungee, is wearing a Hudson’s Bay Company “chief ’s coat” and a medal with a bust of George III honoring his loyalty to Britain during the War of 1812. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Presentation medals were used as diplomatic gifts as early as the sixteenth century, but the idea of creating them for use on exploratory expeditions is generally attributed to Sir Joseph Banks (Fig. 5), the influential naturalist who accompanied James Cook (Fig. 11) on his first expedition around the world (1768–1771). Seeing the opportunities for formal interactions with foreign leaders, and the trade and political expansion that such contact might create for Great Britain, Banks concluded that if Cook and his officers had elegant gifts to present, it would enhance their own status as representatives of the British Empire and afford the native recipients of these tokens the symbols of authority they might need to reinforce any agreements made during their negotiations. Such objects would also serve as irrefutable, dated records that representatives of the British crown had visited the areas where the medals came to reside. And so, in the spring of 1772, after his return from Cook’s first expedition, and in anticipation of participating in the next one then being planned, Banks approached the Birmingham firm of Boulton and Fothergill (later Boulton and Watt) and commissioned the design and manufacture of a medal to be used for this purpose.1 Struck in gold, silver, and brass, the medal bore the likeness and title of George III on one side, and the names, images, and expected departure date of Cook’s two ships, HMS Resolution and Adventure, on the other (Figs. 1a, 1b).

Fig. 3. George Lowery, artist unknown, nineteenth-century. Oil on canvas, 29 ½ by 26 ¼ inches. Lowery, a Cherokee chief, is wearing a President James Monroe Peace Medal. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

When Banks withdrew from his role in the expedition due to disagreements with the admiralty, he passed the bill for the medals onto them. They paid, then turned the medals over to Cook with the understanding that he would give them to any figures of authority he might meet on his travels. Cook used Banks’s Resolution and Adventure medals on both his second and third expeditions (1772–1775 and 1776–1780), distributing them among the people he met from the South Pacific to Nootka Sound, Alaska.2 It is believed that as many as two thousand of the brass medals were struck and carried on Cook’s trips, while the 142 silver ones were kept at home.3 Of the two gold medals Banks had struck (and paid for), he gave one to the king (now at the British Museum) and the other to Cook’s wife.4

Fig. 4a. Baudin Expedition Medal, 1800. Brass, diameter 1 1/2 inches. On the obverse: Portrait bust of Napoleon Bonaparte with “EXPEDITION DE/ DÉ COUVERTES/ AN. 9” below and “BONAPARTE PREMIER CONSUL DE LA REP. FRANCE around the edge. Private collection.

Fig. 4b. Reverse of Fig. 4a. “LES CORVETTES/ LE GÉOGRAPHE ET/ LE NATURALISTE, /COMMANDÉES PAR/LE CAPITAINE/ BAUDIN.” Private collection.

In the decades that followed Cook’s worldwide travels, other countries followed his precedent and issued medals of their own. Not to be outdone in the sphere of exploration, Louis XVI had a medal struck for Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse, to take with him on a scientific exploratory trip to the Pacific Ocean from 1785 to 1788. The idea behind the expedition was to complete Cook’s exploration of the Pacific as well as to search for the Northwest Passage. After covering vast amounts of ocean and making coastal surveys in California, Hawaii, Alaska, Japan, and Australia, the French frigates Astrolabe and Boussole ran aground on a reef in the Solomon Islands in Melanesia and all 223 of the officers and crew aboard were lost. It is not known how many medals were distributed before the ships went down.

Fig. 5. Portrait of Joseph Banks (1743–1820) by Benjamin West (1738–1820), 1771–1772. Oil on canvas, 92 by 63 inches. The likeness was painted after Banks’s return from Captain Cook’s first voyage around the world. The Collection: Art & Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery), Lincoln, England.

As a student at a Paris military academy, Napoleon Bonaparte had considered applying to participate in La Pérouse’s voyage. His sensitivity to the loss of the expedition encouraged him to support the only French scientific expedition made to the Pacific during his reign as emperor. That surveying trip to Australia (1800–1804) carried a supply of medals handsomely struck with a bust of Napoleon on one side (Fig. 4a) and the names of Nicolas Baudin and the corvettes Géographe and Naturaliste on the other (Fig. 4b). Struck in Paris in 1800, they were dated “year 9,” referring to the number of years since the founding of Napoleon’s republic. In his diary Baudin reports giving one medal to the captain of an English ship encountered early in his voyage,5 and placing four others on aboriginal graves near King George Sound in Australia.6 Others were undoubtedly distributed en route.

Fig. 6. Reverse of HMS Beagle/ Adventure Expedition Medal, 1827. Brass, diameter 1 inch. Inscribed “GEORGE IV.” and “H[is]• B[ritannic]•M[ajesty’s]• S[hips]. ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE 1827.” National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Fig. 7. H.M.S. Beagle in the Straits of Magellan by R. T. Pritchett (1828–1907), c. 1890. Signed “R. T. Pritchett.” at lower right, inscribed “H.M.S. BEAGLE.” at lower left. Watercolor on paper, 4 by 6 inches. This painting, engraved for the frontispiece of Charles Darwin’s Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage Round the World of H.M.S. ‘Beagle’ Under the Command of Captain Fitz Roy, R.N. (London, 1890), is reproduced here in its original form for the first time. Private collection.

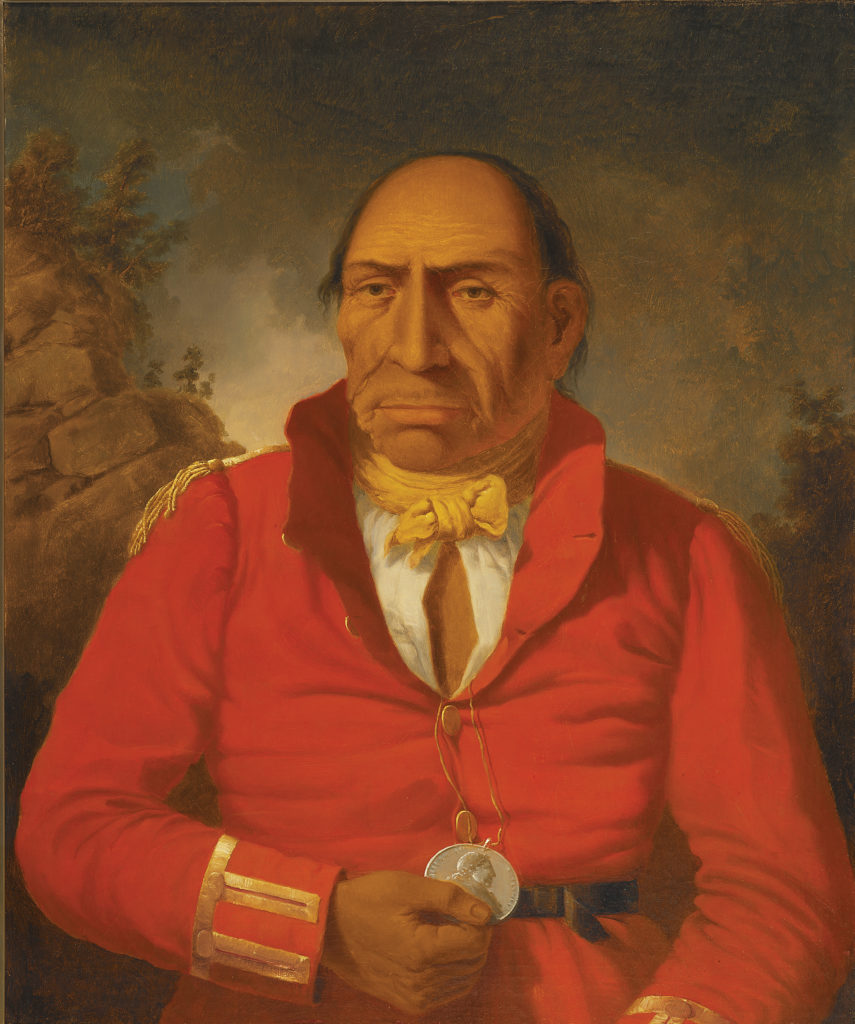

Each expedition leader decided how many medals to give away and to whom. Sir John Franklin, whose name is indelibly linked to his ill-fated final voyage in search of the Northwest Passage (1845–1848), had attempted to uncover information about the Canadian Arctic much earlier in his career with combined maritime and terrestrial expeditions. His land travel put him in contact with native Inuit families to whom he gave gifts of both practical trade goods and medals. In the published narrative of his first overland voyage in the high Arctic (1819–1822), Franklin makes several references to giving medals to the people who were of help to his party. “I then gave him a medal,” he reported of one such exchange, “telling him [that the bust depicted on it] was the picture of the King, whom they emphatically term ‘their Great Father.’”7 Later in the same volume, Franklin refers again to giving a medal, writing: “I then decorated him with a medal similar to those given to the other chiefs. He was highly pleased with this mark of our regard, and promised to do every thing for us in his power.”8 In a third such reference Franklin noted succinctly, “As an introductory mark of our regard, I decorated him with a medal.”9 The medals Franklin was presenting were probably similar to those given to Indians who remained loyal to the British during the War of 1812.

Fig. 8a. HMS Terror Expedition Medal, 1836. Brass, diameter 1 1/4 inches. On the obverse: Britannia seated, with a laurel branch in her right hand, a triton in her left, and Union shield at her side. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Fig. 8b. Reverse of Fig. 8a. Royal crown above “H.M.S. TERROR/ CAPTN BACK/1836.” National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

When Franklin’s fellow Arctic explorer George Back made an exploratory trip to the same area aboard HMS Terror in 1836, he described the medals he was carrying in a brief account in his report: “Four noisy natives of the Esquimaux race had the hardihood to venture through much difficult drift ice to the ship, from whence, however, they returned amply rewarded, and the richest of their tribe. Some of the presents, supplied for that purpose by government, were given to them, together with a few brass medals, having the ship’s name on one side, and a figure of Britannia on the other” (Figs. 8a, 8b).10

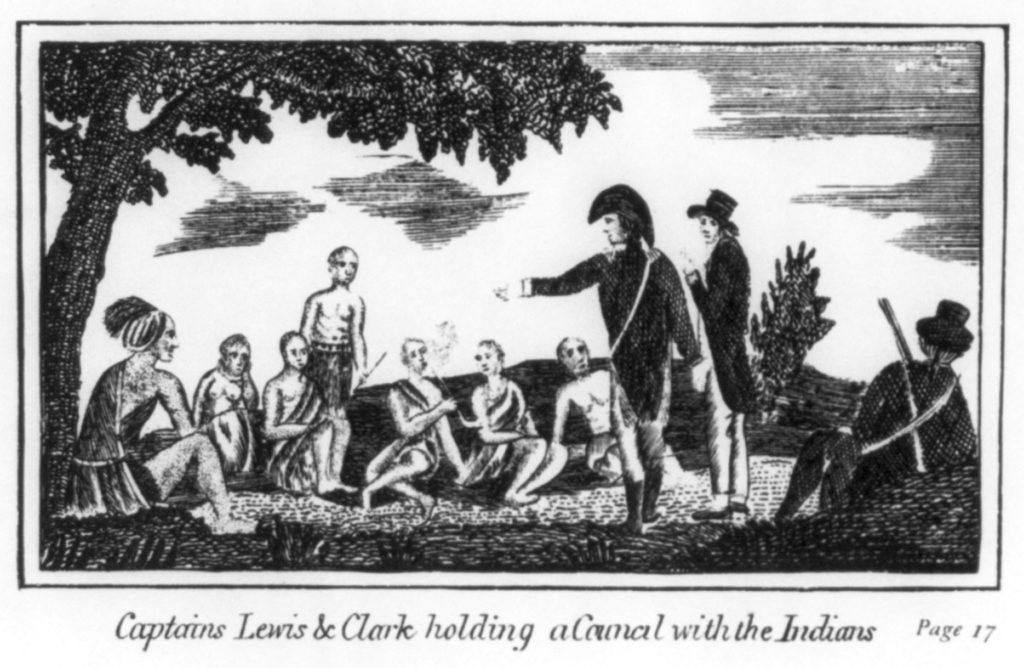

Fig. 9. Captains Lewis & Clark holding a Council with the Indians, artist unknown, published in Patrick Gass, A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of A Corps of Discovery (Philadelphia, 1810) opp. p. 26. Woodcut, 2 ¾ by 4 ¾ inches. Lewis and Clark often incorporated the gift of Jefferson Peace Medals in meetings such as this, requesting that, in return, the Indians give them any Spanish, French, or British medals that they might already have. The expedition carried at least eighty-nine Jefferson medals, in three different sizes, to present to Indian leaders during their trip.

An almost identical medal, and possibly the model used for the design of Back’s Terror medal, was carried aboard HMS Beagle and its companion ship HMS Adventure during their first trip along the South American coast from 1826 to 1830 (see Fig. 7)11 “Previous to the expedition quitting England,” noted the Beagle’s captain, “I had provided myself with medals, to give away to the Indians with whom we might communicate, bearing on one side the figure of Britannia, and on the reverse ‘George IV’, ‘Adventure and Beagle’ and ‘1826.’”12 Other examples of the medal survive that bear the dates 1827 (Fig. 6) and 1828. In his narrative of the trip, Captain Philip Parker King recorded the effect these special tokens had on establishing positive relationships with the natives of Patagonia. “When Mr. Cooke [one of King’s officers] landed he presented some medals to the oldest man, and the woman; and suspended them round their necks. A friendly feeling being established, the natives dismounted, and even permitted our men to ride their horses.”13 A number of medals left in a cairn near the Strait of Magellan were rediscovered in 1981. They now reside in the Martin Gusinde Archaeological Museum in Puerto Williams, Chile, the southernmost museum in the world.14

Fig. 10. HMS ‘Resolution’ and ‘Discovery’ in Tahiti attributed to John Cleveley the Younger (1747–1786), (1770–1790). Oil on canvas, 18 by 23 inches. This painting depicts Cook’s third and final expedition of 1776–1780. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

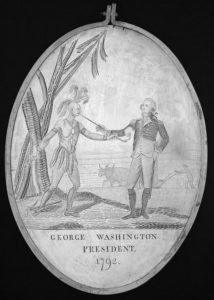

Because the United States government was unable or unwilling to sponsor the extensive global exploration undertaken by England, France, and Spain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it did not create medals exclusively for exploratory purposes. It did make some for more general use in negotiations with Native Americans, however. The first of these, an oval-shaped silver medal of 1789 by Philadelphia silversmith Joseph Richardson Jr., shows Minerva or Columbia greeting a barefooted Indian who drops a hatchet with one hand while accepting a peace pipe with the other (Fig. 13). This design was soon replaced by one showing George Washington extending a hand of friendship to a moccasined Indian who is already wearing a medal and smoking a peace pipe. A white settler plows his fields near a small cabin behind them (Fig. 14). On the reverse of both medals are slightly different designs of the great seal of the United States.

Fig. 11. Captain James Cook, 1728–79 by Nathaniel Dance (1735–1811), 1776. Oil on canvas, 50 by 40 inches. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

When Thomas Jefferson assumed the presidency in 1801, the government replaced the engraved Washington medals with sculpted and struck, round medals (Figs. 12a, 12b) bearing a bust of the new president (see “Thomas Jefferson’s Letter Rack,” p. 92). Lewis and Clark made important use of these as gifts to Native Americans on their journey across North America between 1804 and 1806 (see Fig. 9).15 Similar medals were presented to Indians visiting the capital, and were used at government outposts in the West to reinforce American political dominance there. In return for such gifts, Indians were encouraged to surrender any medals they may have received from foreign governments. While the presidential portrait changed on the medals of each administration, an image of shaking hands and the words “PEACE AND FRIENDSHIP” was retained on the reverse.

- Fig. 12a. Jefferson Peace and Friendship Medal attributed to John Reich (1768–1833) and Robert Scott (1744–1823), 1801. Silver, diameter 4 ½ inches. On the obverse: Bust of Thomas Jefferson with the inscription “TH.JEFFERSON PRESIDENT OF THE U.S.A.D.1801”. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Numismatic Collection.

- Fig. 12b. Two hands shaking, with a peace pipe and hatchet above and the inscription “PEACE/ AND / FRIENDSHIP.” National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Numismatic Collection.

- Fig. 13. Obverse of Washington Peace Medal by Joseph Richardson Jr. (1752– 1831), c. 1789. Silver, 5 3/8 by 4 1/8 inches. Minerva or Columbia (right) presents a peace pipe to an Indian chief, with the inscriptions “G. WASHINGTON. PRESIDENT.” at the top and “1789,” the date of his inauguration, below. Winterthur Museum, Delaware.

- Fig. 14. Obverse of Washington medal attributed to Richardson, c. 1792. Silver, 7 1/8 by 4 7/8 inches. Washington greets an Indian chief wearing a similar medal around his neck and smoking a peace pipe. Inscribed “GEORGE WASHINGTON/ PRESIDENT./ 1792.” Washington presented a medal like this to the Seneca chief Red Jacket at a conference held in Philadelphia in March 1792. Library and Archives Canada.

Medals presented by English and European explorers on their travels throughout the world, and the so-called “peace medals” given to and proudly worn by native people in North America (see Fig. 2, 3, 15), document a high watermark in the history of interracial diplomacy. Sadly, in the years that followed, it was the donors, not the recipients, who usually gained the most from the exchanges they record. These glittering tokens of friendship are among the few positive symbols of contact that survive. They are poignant reminders of the good will that once existed between cultures, but that rarely stood the test of time.

Fig. 15. Shón-ka-ki-he-ga, Horse Chief, Grand Pawnee Head Chief by George Catlin (1796–1872), 1832. Oil on canvas, 29 by 24 inches. He wears a President James Monroe Peace Medal. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.

I am deeply grateful to all the institutions that provided images for this article.

ROBERT MCCRACKEN PECK, the curator of art and artifacts and Senior Fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia, is a frequent contributor to ANTIQUES.

1 For a discussion of Banks’s medals, see Arthur Westwood, Matthew Boulton’s ‘Otaheite’ Medal… (Assay Office, Birmingham, UK, 1926); and L. Richard Smith, The Resolution and Adventure Medal (Wedgewood Press, Sydney Australia, 1995). I am grateful to Peter Lane for his assistance on my research of the Cook medals. See his “Captain Cook’s exploration medals,” in reCollections, an online publication associated with the National Museum of Australia at http://recollections.nma.gov.au. 2 John W. Adams, The Indian Peace Medals of George III, or, His Majesty’s Sometime Allies (G.F. Kolbe, Crestline, CA, 1999), p. 134; see also Smith, Resolution and Adventure Medal, p. 15. 3 Adams, Indian Peace Medals, p. 134. Examples of both medals are in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. I am grateful to Melanie Vandenbrouck, Debbie Williams, and Claire Warrior for showing them to me in December 2016. I am grateful to Arni Brownstone for showing me the Resolution and Adventure medal in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum in May 2017. 4 The Letters of Sir Joseph Banks, 1768–1820, A Selection, ed. Neil Chambers (Imperial College Press, London, 2000), p. 55. 5 At the time, France and Great Britain were officially at war, but Baudin had been granted permission to travel through British-controlled territories to pursue scientific studies. He used the medal as a goodwill token to discourage interference by his British counterpart aboard the frigate Proselyte. After visiting the British ship, and making friends with the captain, Baudin invited him back to his own ship for an inspection. “Upon his departure,” Baudin recorded, “I begged him to accept a medal struck to commemorate the voyage, which he did with pleasure, and then we parted.” Nicholas Baudin, The Journal of Post Captain Nicholas Baudin Commander-in-Chief of the Corvettes Géographe and Naturaliste…,” trans. Christine Cornell (Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1974), p. 12. 6 Ibid., pp. 486–487. 7 John Franklin, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea, in the years 1819, 20, 21, and 22 (London, 1823), p. 276. 8 Ibid., p. 310. 9 Ibid., p. 334. 10 George Back, Narrative of an Expedition in H.M.S. Terror, Undertaken with a View to Geographical Discovery on the Arctic Shores in the Years 1836-7 (London, 1838), p. 416. 11 This is a different Adventure from the ship used on Captain Cook’s second voyage and depicted on the Banksian Resolution and Adventure medals. 12 Robert Fitzroy and Philip Parker King, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle, between the Years 1826 and 1836… (London, 1839), vol. 1, p. 17. 13 Ibid. 14 The last recorded use of the Adventure-Beagle medals by members of the expedition is May 21, 1829. For an account of the deposit and discovery of this cairn, see Andrew C. F. David, “Discovery of Relics on Mount Skyring of Beagle’s Survey of Magellan Strait,” The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 68 (1982), pp. 40–42. 15 For a discussion of the medals given away by Lewis and Clark see Francis Paul Prucha, Indian Peace Medals in American History (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1971), pp. 16–24; Castle McLaughlin, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis & Clark’s Indian Collection (University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2003), pp. 44–47; and Carolyn Gilman, Lewis and Clark Across the Divide (Smithsonian Books, Washington, DC, 2003), pp. 33–36 and 221.