from The Magazine ANTIQUES, March/April 2012 |

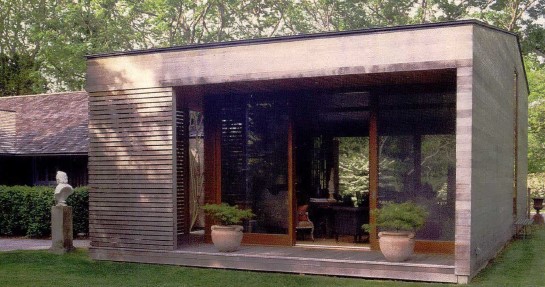

Fig. 1. Ted Porter of Ryall Porter Sheridan Architects designed the extension to the original 1930s Swedish log cabin. It measures thirty-nine by twenty-three feet and is clad in thin horizontal slats of smoothly finished Western red cedar. Outside is a white marble Victorian bust of John Bright (1811—1889), an English parliamentarian and antislavery advocate admired by Abraham Lincoln, who kept a photograph of Bright in the White House. President Obama also has a bust of Bright prominently displayed.

Downsizing-a midlife rite of passage common to those whose offspring have grown up and moved out-is not a contingency that his friends would have ever dreamed possible of the abundance-loving Paul F. Walter, the New York connoisseur renowned for the scale and quality of his pathbreaking collections, which have run the gamut from Indian miniature paintings and early photography to nineteenth-century British decorative arts and African tribal pottery. Walter is one of those exceptional aesthetic bellwethers who has had far-reaching effects not only on the formation of contemporary taste, but also on the direction of art markets.

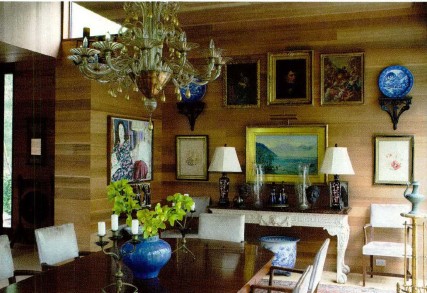

Fig. 2. In the foreground of this view of the new room are vellum-upholstered dining chairs designed by Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) that came from his daughter’s house.

Fig. 4. Detail of an early twentieth-century copy of a William Kent table.

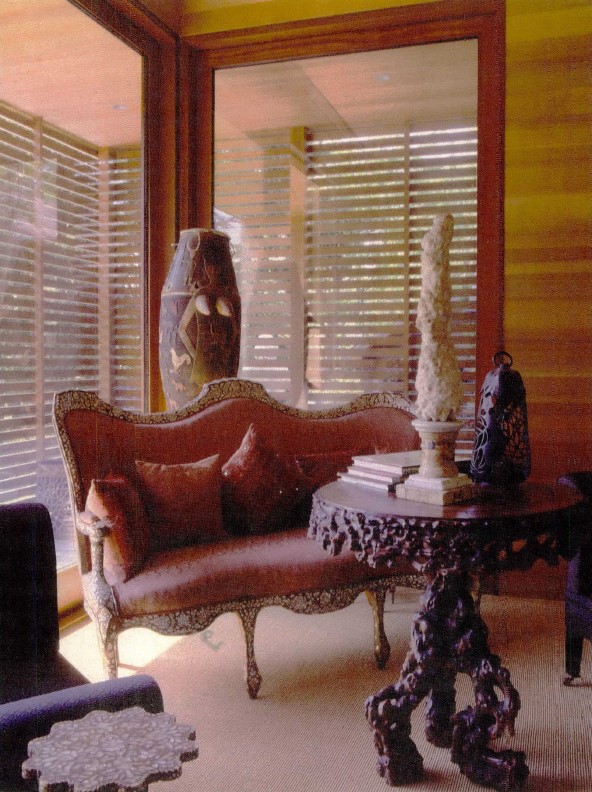

Fig 10. The large basket on the eighteenth-century Chinese table is by Jeremy Frey, a contemporary Indian basketmaker from northern Maine. The sofa against the wall in ninteenth-century Chinoiserie style came from a Hollywood movie studio and is Indian. A painting from the early 1970’s by Humphrey hangs over it.

Fig 3. The Venitian chandelier in the dining area is twentieth century. On the table are blue ceramic vase by Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) and candlesticks by W.A.S. Benson (1854-1924). A landscape by John William Inchbold (1830-1888) hands over a sideboard by Lutyens. The English watercolor of Vesuvius at the top left dates from the ninteenth century.

During more than a half-century of incessant, not to say obsessive, acquisition (which at times required a full-time private curator just to keep track of his almost daily purchases) Walter, now seventy-six, transformed his two residences-a glamorous river view apartment in a celebrity packed 1920s tower on Manhattan’s East Side, and a sprawling arts and crafts mansion in the estate section of Southampton on the East End of Long Island-into what cognoscenti have considered irrefutable evidence of an eye unsurpassed in his generation. As a result, there was widespread dismay among what might be termed the Walterati when around the turn of the millennium he announced that he would give up his Southampton house for something more manageable.

Fig 5. Among the furnishings of the dining area is, at the left, a painting of Paul Walter’s nieces by Billy Sullivan (1946-).

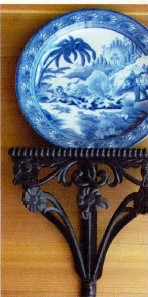

Fig 6. One of a pair of early nineteenth-century English ceramic plates with designs taken from Indian prints, on a nineteenth-century Indian bracket.

A visit to that brilliantly integrated ensemble was the closest one could come in this country to a time-warp reincarnation of an English country house before the Great War. The half-timbered-and-red-brick residence of about 1900 was decorated for Walter in the high aesthetic movement style by the architect and interior designer Mark Kaminski, who deployed an astonishing quantity of museum-worthy furnishings and artworks against a dazzling backdrop of complex Victorian era wallpapers layered to virtuoso effect. The surrounding English style grounds were laid out by the landscape designer Deborah Nevins, and deemed by no less an authority than Nigel Nicolson to be the American equivalent of the legendary gardens cultivated by his parents, Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West, at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent.

Despite the déménagement that so upset Walter’s circle (especially his frequent and numerous summer houseguests), he wanted to maintain a presence in the Hamptons. He soon discovered the perfect interim rental near the north shore of the South Fork-a charming 1930s Swedish log cabin (a designation based on its rough-cut wood siding, set vertically rather than horizontally in the American manner). Although his new house in its entirety might have fit into the capacious drawing room wing that Kaminski, who died in 1993, appended to the Southampton mansion, Walter never found anything more to his liking and eventually decided to buy the cabin.

Its somewhat claustrophobic interiors were antithetical to the gracious sequence of spaces in his earlier house: dark and inward turning, paneled in knotty pine, and infinitely more informal if also undeniably chic. This was a rustic camp in the woods ready for Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, rather than sophisticated salons befitting Cecil Beaton and Greta Garbo (the latter was Walter’s longtime downstairs neighbor in the city; the former, her erstwhile beau, designed several of the collector’s most delightful oddments, including masks and headdresses for the Metropolitan Opera’s acclaimed 1961 production of Turandot).

Because there was no room for all of Walter’s elegant clutter in the new place, most of his Southampton furnishings went into storage, and a good deal of it was eventually auctioned off in a closely watched sale at Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York. But culture vultures who had hoped to swoop in and snag his choicest possessions were sorely disappointed, because this canny acquisitor held back his most notable prizes.

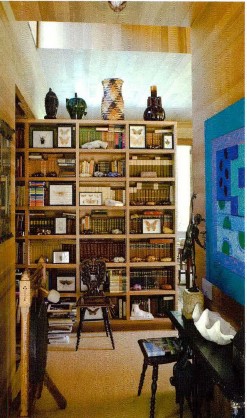

Fig. 7. The bookcase filled with nineteenth century English and American ceramics is one that Lutyens designed for the offices of Country Life. The sideboard is also by Lutyens. The painting above it is by Ralph Humphrey (1932-1990) from the early 1970s. The glass case on the side table holds a procession of Indian figures made in the nineteenth century.

Fig. 8. A contemporary Cherokee basket is surrounded by Christopher Dresser pots on the top of the bookcase. The painting to the right is by Humphrey.

As Walter had done with earlier Long Island summer rentals before he bought the Southampton spread in 1986, he immediately accessorized the cabin with juxtapositions of objects that conventional collectors would never hazard. For example, a spectacular art nouveau copper electrolier by the English metalwork master W.A.S. Benson found a surprisingly sympathetic spot above the dining table, its free-flowing lines nicely echoed by Ben Seibel’s mid-century modern Raymor Roseville plates (in the coveted mottled-green “frogskin” glaze), which centered the place settings below.*

Soon after he settled in, Walter realized that the house was too small even for his scaled-back expectations and began planning an expansion that again demonstrated his keen intuition for unexpected turns that turn out to be just right. Rather than extending the cabin with a reproduction of the quaint original, Walter asked Ted Porter, a partner in the New York firm of Ryall Porter Sheridan Architects, to design a generously proportioned all-purpose entertaining space, measuring thirty-nine by twenty-three feet, which would reinterpret the woodsy feeling of the log cabin while being unmistakably modern. Porter’s expert execution of his client’s concept was faultless, and the alike-but-unlike qualities of the expansion spurred intriguing synergies between old and new.

The architect chose unstained smoothly finished Western red cedar cladding that he applied horizontally to the exterior walls in thin, openly spaced slats to contrast with the chunky vertical logs of the existing structure. The east and west ends of the oblong pavilion were fitted with floor-to-ceiling window walls that slide open to the outdoors, giving onto a sloping lawn at the front of the property and an improbably exuberant freeform swimming pool at the back-a holdover from the previous owners that Walter, never averse to an enlivening bit of kitsch, decided to leave in situ.

Given the fully integrated decor of his Southampton house, it is remarkable that Walter’s selections from that elaborately staged setting look equally good here against the neutral backdrop of horizontally paneled cedar interior walls, which soar to eleven-foot-high ceilings. This simple container allows the form and detail of each object to stand out clearly, and even those familiar with Walter’s collection now look afresh at pieces he has owned for ages.

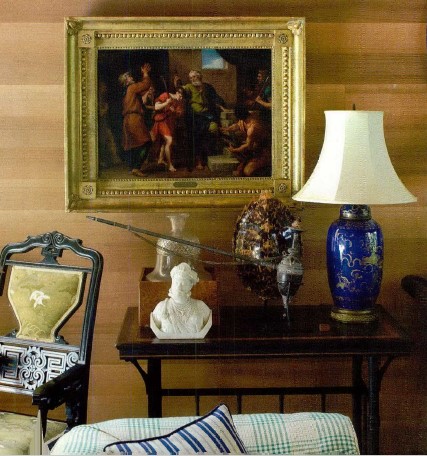

Fig. 9. An eighteenth century Italian painting hangs over a nineteenth century Indian marble bust of a maharajah.

Among the several major works that appear to better advantage in their new setting is a glass-paned bookcase more than ten feet tall designed by the architect Edwin Lutyens for his Country Life magazine headquarters of 1904 in London (Fig. 7). The British financier and arts patron Jacob Rothschild owns an identical pair; all retain their original apple green painted finish. Walter’s example stands next to a 1920s Lutyens walnut sideboard with ivory drawer pulls, part of an extensive suite of dining room furniture the architect created for one of his daughters. Given Lutyens’s central role in building New Delhi, the British imperial capital of the Raj, it is fitting that a number of adjacent pieces are Anglo-Indian, including a curvaceous rosewood-and-cane Regency sofa, Mughal style inlaid occasional tables, and small-scale sculptures from all over the subcontinent in stone, metal, and wood.

Large-scale paintings emphasize the bold scale of the addition, and are “skyed” upward as in the stately houses of England and London’s Royal Academy. Walter’s taste in pictures is no less offbeat and self-assured than his much-imitated forays into unknown realms of the decorative arts. The walls of the new addition are hung with rarely seen works that include luminous landscapes by the little-remembered John William Inchbold (see Fig. 3), a Pre-Raphaelite greatly admired by John Ruskin, and brooding monochromatic canvases by the now-forgotten Ralph Humphrey (see Figs. 7, 10), a missing link between abstract expressionism and minimalism.

Fig. 11. The nineteenth-century mother-of-pearl-inlaid settee is Syrian and the tripod root table is nineteenth-century Chinese. The carved stalactite on the table is English and was done in the nineteenth century. The large wood drum is West African, probably late nineteenth century, and bears the name Queen Victoria.

Fig. 12. A copper electrolier designed by Benson c. 1899 hangs over a nineteenth-century English zebrawood table in the original part of the house, a 1930s Swedish log cabin.

Walter is the least pedantic of collectors, and he wears his decades of pioneering amateur scholarship very lightly indeed. There is nothing the slightest bit didactic in the way he has arranged his spectacular array of treasures from seemingly every epoch and culture. But it would be a foolish guest indeed who did not consider even an hour in one of his houses to be nothing less than a crash course in the visual arts at their finest and most life enhancing.

MARTIN FILLER writes regularly on art and architecture for the New York Review of Books.