Fig. 1. A Pair of Leather Clogs by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), 1889. Oil on canvas, 12 5/8 by 16 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

Some years ago, I was attending a Mets game at the old Shea Stadium when, at a crucial moment, the team’s left fielder, Vince Coleman, hit a single. As soon as he reached first base, the crowd began encouraging him, as though with one voice, to steal second: he had broken so many records in base stealing that one could call him, without undue violence to truth, an artist of stolen bases. The JumboTron clearly concurred because, to the mounting excitement of the crowd, its nearly forty-foot screen flashed the words “VINCENT VAN GO!” The point, of course, was that just as Vincent van Gogh was supreme in the art of painting, even so was Vince Coleman supreme in the art of stealing bases.

Fig. 2. Impasse des Deux Frères, 1887. Signed “Vincent” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 13 ¾ by 25 ¾ inches.

I cannot recall, after all these years, whether Coleman did indeed steal second, or even how the game ended (although it is probably a safe assumption that the Mets lost); but I vividly recall thinking that there could be no clearer testament to van Gogh’s superlunary fame than having his name emblazoned across a four-story JumboTron in the expectation that everyone from starstruck ten-year-olds to their beer-besotted elders would instantly recognize it and understand what it was doing there.

Fig. 3. The Langlois Bridge at Arles, 1888. Oil on canvas, 19 ½ by 25 inches. Wallraf-Richartz Museum and Corboud Foundation, Cologne.

History may record no more remarkable transvaluation than the posthumous apotheosis of van Gogh, that timid and retiring painter of postimpressionist flowers and fields: he is now a god, or at least a saint, in our secular cult of visual art. As all the world knows (even ten-year-olds and their beer-besotted elders), van Gogh’s short and miserable existence was lived in apostolic poverty and ended in sickness and suicide. But if there is one thing that the world knows even more clearly, it is that his paintings are now incalculably precious. This is true to such a degree that many viewers will likely be drawn to Vincent van Gogh: His Life in Art, a new show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, as much by a sense of the artist’s fame and the monetary value of his work as by the prospect of aesthetic response.

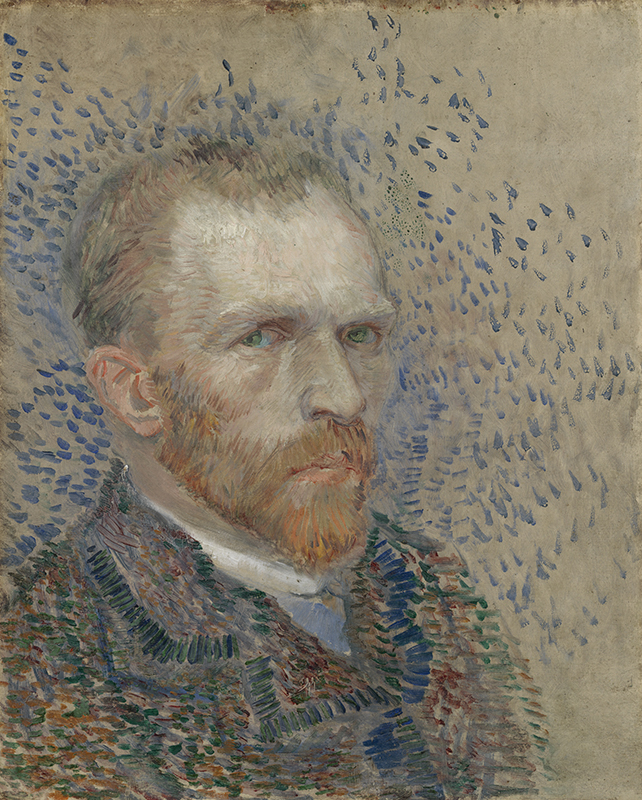

Fig. 4. Self-Portrait, 1887. Oil on cardboard, 16 1/8 by 13 inches.

In the exhibition’s catalogue, one reads with amazement a letter from van Gogh to his brother Theo, stating that, “I can do nothing about it if my paintings don’t sell. The day will come, though, when people will see that they’re worth more than the cost of the paint and my subsistence, very meagre in fact, that we put into them.” And as we read, all of us are in on the cosmic joke: van Gogh, who would now be one of the richest men on earth, whose diminutive works are the most extravagant trophies of power and wealth, aspired to see the day when the world would acknowledge, not his greatness—he was far too modest for that—but simply the fact that his paintings were worth more than the cost of their materials. Corollary to our amazement is the certainty that if we had been in Paris or Arles in the 1880s, surely we would have recognized those gifts that eluded all but a handful of his contemporaries. Perhaps—and perhaps not.

Fig. 5. Head of a Woman Wearing a White Cap, 1884–1885. Oil on canvas, 17 3/8 by 14 1/8 inches. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands, © Kröller-Müller Museum; photograph by Rik Klein Gotink.

Fig. 6. Old Man in a Tailcoat, 1892. Graphite with scraping, traces of fixative and squaring on wove paper, 18 5/8 by 10 1/4 inches.

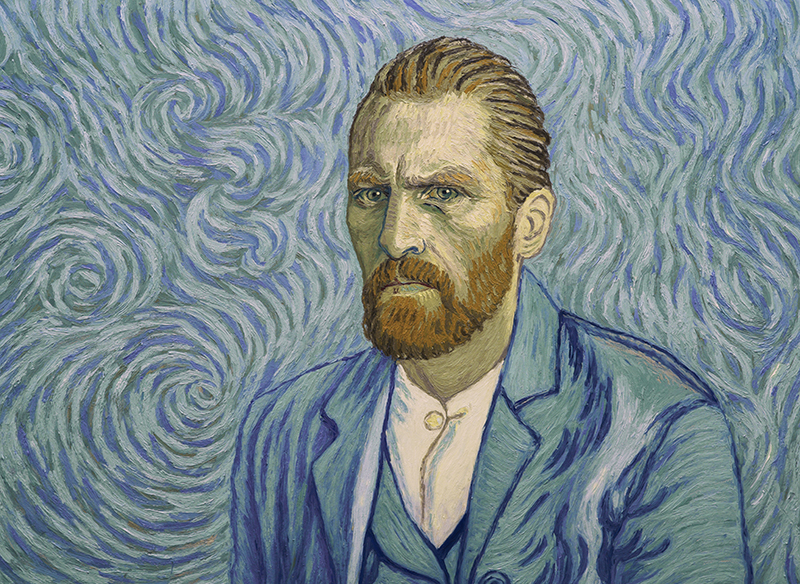

However that may be, the world that once ignored this sad and solitary Dutchman now seems fixated on his troubled life, as two recent and well-received feature films, Loving Vincent and At Eternity’s Gate, can attest. The Houston show, for its part, illustrates that life through fifty-three of van Gogh’s paintings and drawings, almost as though they were so many entries in a diary. Included among a number of less ambitious works are several indisputable masterpieces. Most of them are drawn from two Dutch collections, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the Kröller- Müller Museum in Otterlo. And although this biographical approach is not exactly innovative, any excuse for displaying an artist of such excellence will do just fine.

Fig. 7. Peasant Woman Binding Sheaves (after Millet), 1889. Oil on canvas on cardboard, 17 by 13 inches.

More fully than the two recent films, which focus on the final tragic months of his life, the Houston show gives us a sense, although necessarily abbreviated, of van Gogh’s entire career. Despite our popular image of the man and of the subject matter he favored, van Gogh was hardly a peasant. Rather he was the son of well-educated and well-to-do parents (his father was a pastor) who were acutely conscious of their rank and standing in the Dutch haute bourgeoisie. It is in that context that one must understand their alarm at those early signs of eccentricity that eventually burst into blazing madness.

Fig. 8. In the Café: Agostina Segatori in Le Tambourin, 1887. Oil on canvas, 21 7/8 by 18 ½ inches.

And yet, surprisingly for so austere and bourgeois an upbringing, the young Vincent’s interest in art was stimulated and to some degree encouraged by his parents. His mother, who would afterward prove so resistant to his career in art, was the first to teach him drawing. One of his relatives who had been a successful sculptor and a cousin by marriage was Anton Mauve, a leader of the Hague school, that highly regarded Dutch response to the realist and impressionist movements in France. At the same time, three of van Gogh’s uncles (like his brother Theo) were art dealers, and one of them arranged for him to work at Goupil & Cie, an important art gallery in the Hague. For several years he was very gainfully employed by the gallery, to the extent that they sent him to work in their Paris and London offices. But ultimately this success failed to satisfy a deeper need, and at the relatively advanced age of twenty-seven, after he had studied for a time to become a minister, van Gogh decided to switch careers and take up painting as a profession.

Fig. 9. Robert Gulaczyk as van Gogh in the animated film Loving Vincent (2017), directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. Photograph courtesy of BreakThru Films.

That is to say that his entire activity as a painter took place in the final ten years of his life, and it was not really until the final three or even two years, spent in Saint-Rémy and Arles, that he achieved that signature style that the world has come to revere. But in that short period of time, he managed to create more than two thousand works of art, nearly half of them oil paintings. In the course of this foreshortened career, van Gogh passed from such conventional, but still highly accomplished, drawings as Old Man in a Tailcoat (Fig. 6) to a superb self-portrait, painted in oil on cardboard in 1887 (Fig. 4) and the famous Irises (Fig. 11), from May of 1890, completed scarcely two months before he died. All of these are on view in Houston.

Fig. 10. Willem Dafoe as van Gogh in Julian Schnabel’s film At Eternity’s Gate (2018). Photograph by Lily Gavin.

Van Gogh’s mature style—with its sharply impastoed lines, its intuitive but nearly infallible perspectives, the idiosyncratic perfection of its colors and contours—is so well-known and so widely admired that it would seem superfluous, in an article of this length, to remind the world of what it already knows. But it is worth taking a moment to pause and consider and appreciate our admiration. As has been said, many viewers of van Gogh’s works are initially drawn, these days, to an ineffaceable sense of their price and prestige. But once they stand in front of his works—and almost the same point could be made for abstract expressionism—those viewers will almost unanimously, appreciate sincerely and deeply the works’ aesthetic power. Like all great and revolutionary visual artists, van Gogh aspired to teach us to see for the first time something that had been present since the creation, but hidden in plain sight. For that, of course, he must be praised. But as a civilization we have risen to the challenge that he set us, and so it is that most visitors to the Houston show will perceive the subtlest formal, chromatic, and spiritual points that, in 1890, the year of van Gogh’s death, eluded all but a handful of the most advanced spirits of the age. And for that, perhaps, we, too, deserve some measure of praise.

Fig. 11. Irises, 1890. Oil on canvas, 36 ½ by 29 1/8 inches.

Vincent van Gogh: His Life in Art is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, to June 27.