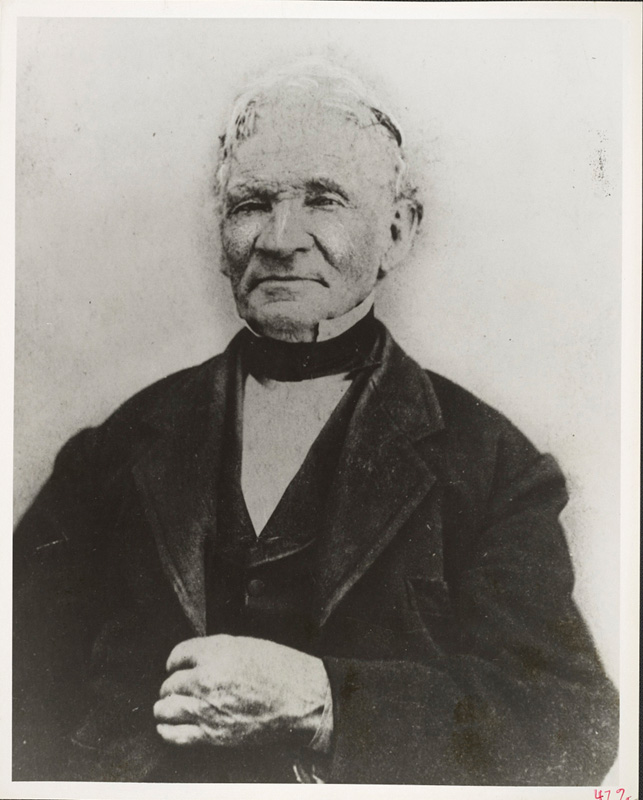

He is one of the most intriguing of the early nineteenth-century American folk artists. Restless and creative, Rufus Porter was among the first of the adventurous and entrepreneurial itinerants who saw the opportunity in painting affordable small watercolor portraits that allowed average people to own images of themselves and their loved ones. Porter also painted fanciful panoramic landscape murals that decorated the interior plaster walls of American homes. A man of science, he was also an engineer and inventor. He advertised to 1849 Gold Rush prospectors that his 350-foot hydrogen-filled dirigible would soon be flying passengers across America from New York to California, and he founded Scientific American, America’s oldest continuously published magazine. Porter personified the early nineteenth-century American belief in infinite progress and the notion that what could be imagined could be accomplished.

Porter was studied for more than forty years by Jean Lipman, editor of Art in America. Her research was presented in two books and in The Magazine ANTIQUES. In recent years, Porter’s celebrated landscape wall murals have been studied in detail. In 2005 the Rufus Porter Museum, which celebrates his life and art, was founded in Bridgton, Maine, while in 2015 the Center for Painted Wall Preservation was established in Hallowell, Maine, to research and preserve painted wall murals. Currently, an exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine, and its superb accompanying catalogue, further examine Porter’s accomplishments. His originality as a portrait painter and mural artist is now more clearly described, as is the second half of his life and the obscurity into which he had fallen by the time of his death.

Rufus Porter was born in West Boxford, Massachusetts, in 1792. In 1801 his father sold the family farm and moved to what was frontier land in Maine. At age eleven or twelve, Porter was enrolled at the Fryeburg Academy in Maine for just two terms at a total cost of $3.00. This was his only documented education past the local schoolhouse.

The problem of limited farmland and too many sons, along with the economic turmoil of the time, forced many of Porter’s generation to seek economic opportunities using their talents. The Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited trans-Atlantic trading, crippled Maine’s economy, and during the War of 1812 eastern Maine was occupied by the British. Porter tried several potential professions, among them shoemaking. He had some success as a musician, taught school, and was a dancing teacher.

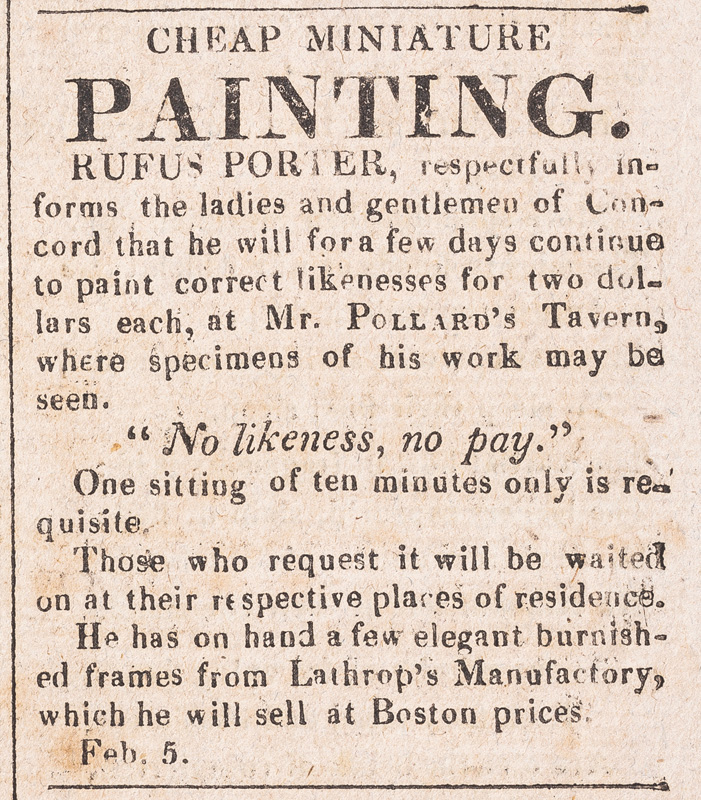

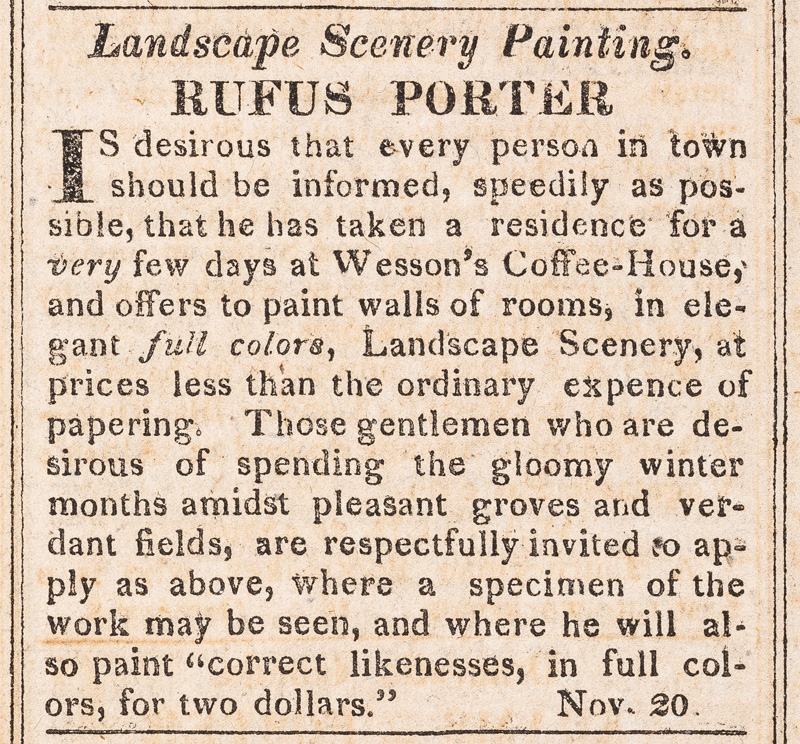

in the Middlesex Gazette (Concord, Massachusetts) on February 5, 1820. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

In 1811 he learned the house- and ship-painting trade in the Portland, Maine, shop of Marcus Quincy. During the War of 1812 he joined the local militia, played the fife and drum in parades, and painted gunboats. In 1815 he married Eunice Twombly in a union that would produce ten children. During this time, he began a career as a portrait painter. It appears that in 1818 and 1819 Porter left his family, even though there were one or two very young children, and joined a trading ship that sailed from New England to the Northwest coast of the United States and Hawaii.

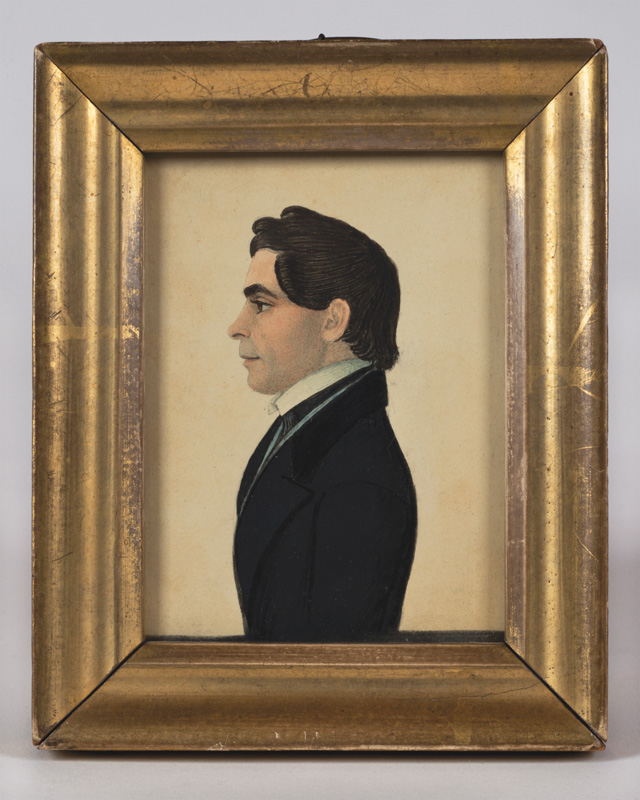

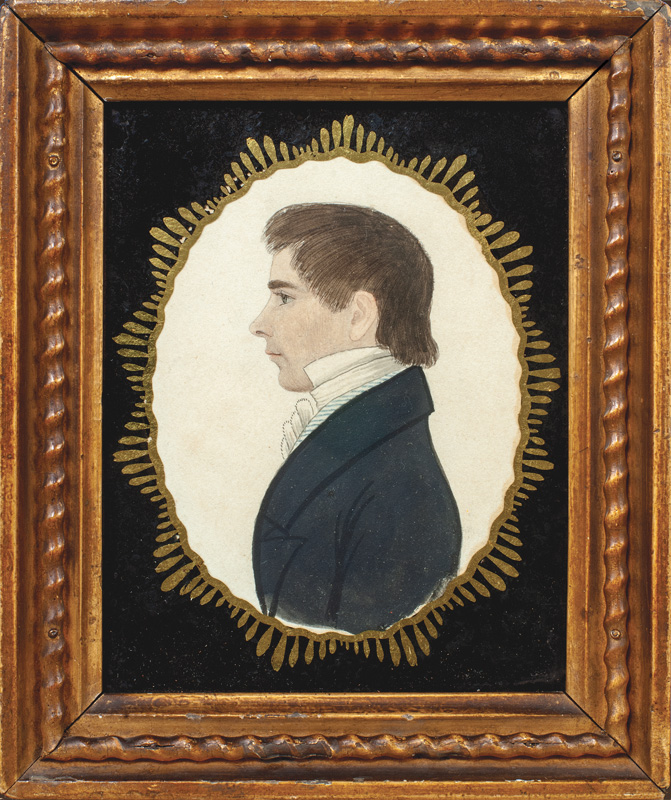

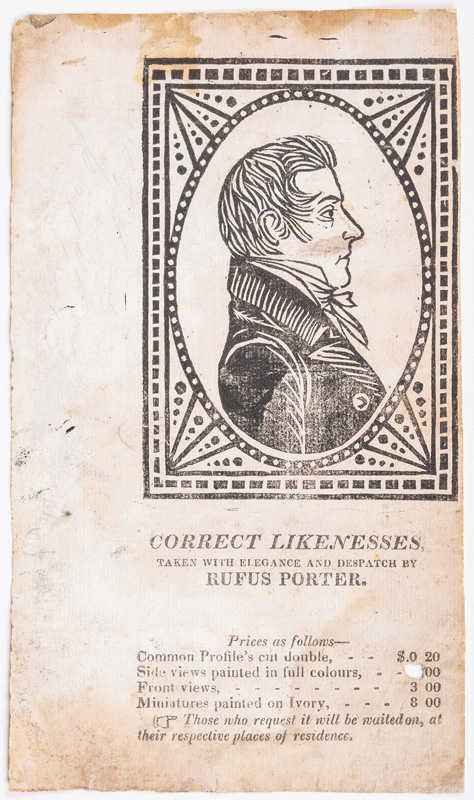

Porter had moved with his family to the Boston area by 1820 and advertised that he painted inexpensive small watercolor portraits (Fig. 4). Small watercolors were in great demand as they were much less expensive than oil-on-canvas portraits and were the only way that most people could afford to preserve images of the family. He had a handbill printed showing prices of 20 cents for a silhouette, $2.00 for a watercolor “side” view on paper, $3.00 for a frontal view on paper, and $8.00 for a miniature on ivory (Fig. 7). Based on surviving examples, most of his portraits were the side views and many have frames with rope turnings and distinctive reverse-painted glasses with gold ray details. Collectors call these “Rufus Porter frames,” and they must have been provided by the artist.

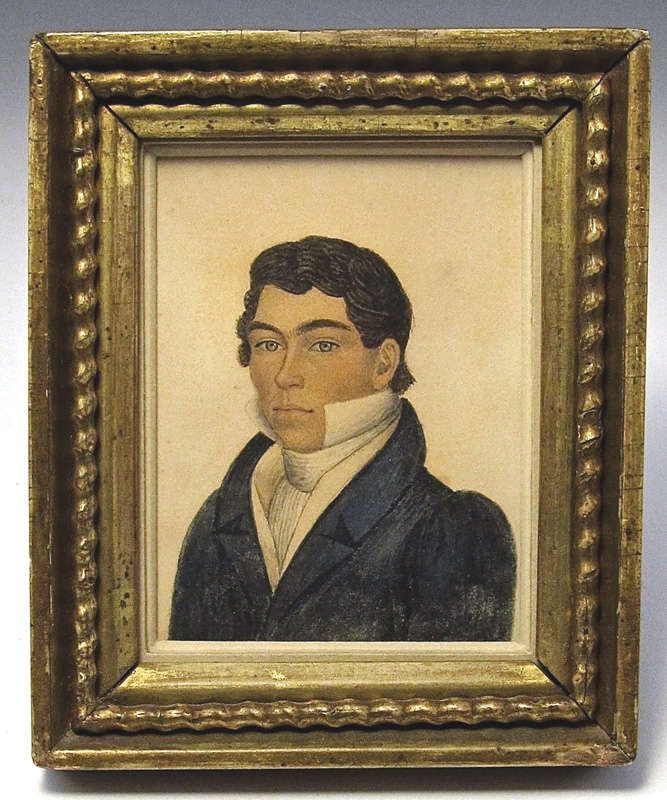

Adams (1807–1839) attributed to Porter, c. 1833. Watercolor and graphite on

paper, 5 1/8 by 4 ¼ inches. Private collection.

Porter used a camera obscura to produce an accurate likeness that could be completed in a few minutes. This device was a wood box with a lens and an interior mirror that reflected the sitter’s image onto a piece of paper, where it was traced and colored.

Adams (1807–1839) attributed to Porter, c. 1833. Watercolor and graphite on

paper, 5 1/8 by 4 ¼ inches. Private collection.

Porter rarely signed his work and only four portraits are known that are either signed or have inscriptions identifying him as the artist. Unsigned portraits, which are offered with some regularity for sale, are readily attributed to him based on the sitter’s characteristic gaze, eye shape, C-shaped ear, and facial palette. Most of his known sitters lived within fifty miles of his family’s home in Billerica, Massachusetts, with the majority of his portraits dating from 1820 to 1830. It also has been suggested that his itinerancy took him as far south as Virginia.

In November 1822, in Providence, Rhode Island, Porter first advertised that he painted landscape panoramas in homes (Fig. 8). Instead of using wallpaper, which was expensive and mounted with wheat paste that attracted insects, it became a tradition to have patterns painted or stenciled directly on the interior walls in American houses. Porter may have learned this craft while working with the two Moses Eatons, a father and son team who were well known for painting interiors with repetitive stenciled designs that imitated wallpaper. Porter’s innovation was to paint entire plaster walls as bright and gay balcony vistas overlooking imagined landscapes (Figs. 9, 10, 13). Bold expressive lines force the viewer’s eye to travel through dramatic perspective changes, from prominent foreground trees to distant views of New England mountains, oceans, villages, and farms. The murals were painted with a combination of freehand drawing and the use of stencils. In a few cases, he painted murals in a single muted color to great effect.

Porter’s landscapes were a part of the “fancy” aesthetic of whimsy that had become immensely popular. Fancy meant exuberant ornamentation that stimulated one’s imagination and awakened the mind while pleasing the eye with light, color, or imaginative forms. While Jean Lipman attributed murals throughout New England to Porter, only three signed by him are known. It appears that a cadre of artists, today known as the Rufus Porter school of painters, also painted mural landscapes. They included several Porter relatives, such as his son Stephen Twombly Porter and his nephew Jonathan D. Poor.

Porter published a small pamphlet in 1820 containing brief do-it-yourself instructions and practical knowledge. In 1825 he expanded this compendium, which was also a recipe book of painting techniques. A section on painting plaster walls describes how Porter manufactured the distemper paint used in his murals by mixing pigment, whiting (ground chalk), hide glue, water, and alum (as a mordant). Four walls of a parlor could be painted in five hours for $10.00, significantly less than the cost of wallpaper. The practical advice in Porter’s book made it quite popular and he boasted that ten thousand copies were sold in one season.

He was also continuously inventing improvements for a variety of items, ranging from clocks to fire alarms to canal boats. Only a few of these inventions were sold. They included an almanac with a revolving data wheel, a carpenter’s level, a cheese press, and a revolving rifle that was purchased by Samuel Colt for $100.

The Panic of 1837 and the resulting recession, which lasted into the mid-1840s, must have greatly reduced Porter’s painting business. In 1840 he moved his family to New York City, where he became a publisher and printed a succession of four newspapers for inventors between 1841 and 1848. These publications were filled with technical subjects as well as poetry, religion, temperance advice, and often had Porter’s own inventions featured on page one. While the 1840s saw great technical advances in many fields, his ideas often focused on transportation and ways to save a farmer time and labor. His readers must have had an unintended laugh with several of his inventions, such as a boat powered by a horse on a treadmill—at a time when hundreds of paddlewheel steamboats plied America’s waterways. Additionally, years earlier in the 1810s and 1820s, there had been ferries crossing the Hudson River powered by a water wheel turned by teams of horses. Many of the ideas Porter promoted were simply unrealistic, such as a self-propelled wheel that somehow worked by perpetual motion.

The third of his newspapers was Scientific American, a four-page weekly started with an investment of $100 and first printed on August 28, 1845. Perhaps to fill space in the newspaper, Porter wrote twenty-eight essays describing his knowledge of painting. These descriptions represent a unique treatise on a folk artist’s use of painting materials and the problems of composition. Included were details about how each pigment was prepared and the precise sequence of steps in painting a portrait. Instructions for landscape mural painting included explanations of the colors, brushwork, and design, such as creating perspective by painting four zones of trees drawn to a precise decreasing height.

When Porter sold Scientific American in 1846 for $800 to the owners of a patent filing company, it had only two hundred subscribers. The new owners transformed the publication, resulting in ten thousand subscribers in 1848 and thirty thousand by 1860.

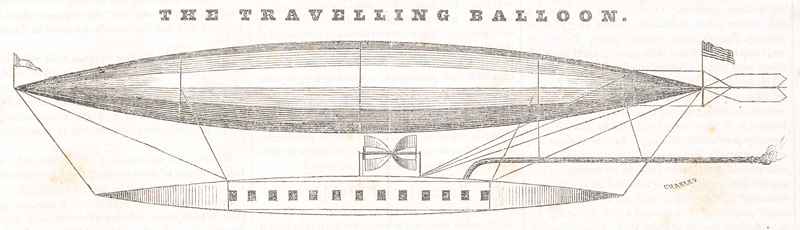

Porter used his publications to promote plans that were first described in 1834 for a steam-powered, spindle-shaped dirigible, filled with hydrogen gas. He claimed that the dirigible could carry fifty to one hundred passengers at fifty or even perhaps one hundred miles per hour (Fig. 11). Its length was variously described as between three hundred and eight hundred feet.

installed in the stairwell of the Howe House by Rufus and Stephen Porter, 1838. Courtesy of the Westwood Public Library, Westwood, Massachusetts.

In November 1848, Porter’s wife died and, a year later, he married Emma Tallman Edgar. Now all of his energy became focused on the dirigible airship. He formed the Aerial Navigation Company and published promotional literature directed to the 1849 Gold Rush prospectors going to California. For $50, he declared that miners could make the trip in just three days of pleasant air travel on the soon-to-be-constructed dirigible. More than two hundred passengers were said to have already purchased tickets.

The myriad problems encountered with building the dirigible were simply glossed over in his descriptions. For example, the dirigible’s lifting power was estimated to be sufficient for flight. However, he greatly underestimated the tremendous weight of the coal that the steam engine required for a coast-to-coast trip. Many aspects of building the dirigible were not possible at this time. Porter simply did not recognize the material, engineering, and technical difficulties.

Westwood, Massachusetts, c. 1834–1837. Painted in watercolor on plaster, it measures approximately four feet tall by ten feet wide. Antiques dealer Stephen Score bought the mural in 1982 from descendants of the original owners, removed it, and reinstalled it in a house in Newtonville, Massachusetts, that same year (shown here). The mural was sold and moved again in 2019 when Score brought it to the Winter Show in New York, where it was sold a third time, and moved to Boston. Photograph by Gabor Demjen.

In 1850 he moved to Washington, DC, to build the “aerial locomotive.” He started a new newspaper, Aerial Reporter, to promote his efforts; sold as many as six hundred shares of $5 stock in the company; and sought a Congressional appropriation. In 1853 he sold tickets to view a twenty-two-foot demonstration model of the dirigible in a Washington saloon.

Scientific American reported that Porter’s 1853 lectures on his flying machine was “as clear as mud” and “so grand and vast, it is enough to make Mount Vesuvius burst out in fiery laughter.” Unable to obtain additional funding, Porter returned to Massachusetts in 1855. At age ninety-two, the last year of his life, he still sought investors for a “wind wheel” that could power ten farm plows at once. While one can suggest that Porter was an unheralded genius and a pioneer in aeronautics, the reality was that the inventions were often just the initial diagrams of his ideas. As his obituary in Scientific American stated: “His inventions were in a manner cast aside as soon as he had roughly completed them, and, heedless of the commercial phases of invention” he moved to his next project. Although Porter’s engineering creations had little impact, his artistic accomplishments survive as a lasting legacy.

Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention In America, 1815–1860 will be on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine to May 31, 2020.

1 Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter, Yankee Pioneer (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1968); Jean Lipman, Rufus Porter Rediscovered: Artist, Inventor, Journalist, 1792–1884 (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1980); Jean Lipman, “The Rediscovery of Rufus Porter,” The Magazine

ANTIQUES, vol. 69, no. 1 (January 1981), pp. 204–211. 2 Linda Carter Lefko and Jane C. Radcliffe, Folk Art Murals of the Rufus Porter School: New England Landscapes, 1825–1845 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2011). 3 Laura Fecych Sprague and Justin Wolff, Rufus Porter’s Curious World: Art and Invention in America, 1815–1860 (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, in association with the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019). We have additionally described the relationship between the economic conditions in America and Porter’s career and have taken a critical view of his inventions. 4 Photography, with the introduction of the daguerreotype, did not occur in America until 1839. The importance of small watercolor portraits at this time is described in Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne, “Images of the American People: Small Portraits from 1820 to 1850,” Antiques and Fine Art, vol. 12, no. 3 (Winter/Spring 2013), pp. 226–233. 5 Deborah M. Child, “Thank Goodness for Granny Notes: Rufus Porter and his New England Sitters,” ibid., vol. 10, no. 4 (Summer/Autumn 2010), pp. 190–195. A maturing of Porter’s painting style can be seen in his portraits; see Sprague and Wolff, Rufus Porter’s Curious World, pp. 60–75. 6 Nina Fletcher Little, American Decorative Wall Painting 1700–1850 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972); and Ann Eckert Brown, American Wall Stenciling 1790–1840, (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2003). 7 Sumpter T. Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee: Chipstone Foundation, 2004). 8 Rufus Porter, A Select Collection of Valuable and Curious Arts, and Interesting Experiments, Which are Well Explained, and Warranted Genuine, and May Be Performed Easily, Safely, and at Little Expense (Concord, NH: Rufus Porter and J. B. Moore, 1825). 9 New York Mechanic, February 1841, p. 1; and Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 429–433. 10 Scientific American, May 28, 1853, quoted in Lipman, Rufus Porter, Yankee Pioneer, p. 44. 11 “Rufus Porter—Representative of American Genius,” Scientific American, vol. 51, no. 19 (November 8, 1884), p. 297.

Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne are collectors and members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the eighteenth article they have published about early American folk portrait painters.