Reexamination of an early Boston easy chair in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art has prompted an elaborate upholstery treatment that reproduces the colorful and showy display of early upholstered seating furniture. Often referred to as the Emerson easy chair because of its history of ownership by ancestors of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), the easy chair is one of thirteen made in Boston and having double scroll arms and turned front legs.1 Based on British precedents, they date from 1705 to 1725, and their creation may have overlapped with the introduction of easy chairs with squared cabriole legs. Milwaukee collectors Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III acquired the chair in the early 1980s from Connecticut dealer John Walton.2 In 1999 the Vogels—longtime supporters—donated it to the PMA in anticipation of the museum’s 125th anniversary.

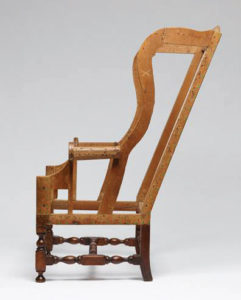

Fig. 1. Easy chair, Boston, 1705–1725. Maple and oak; height 48 1/8, width 31 ¼, depth 35 ½ inches. The height of the feet has been restored, approximately ½ inch at the front and approximately 1 inch at the rear. Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of the Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III Collection for the PMA; except as noted, photographs are by Timothy Tiebout.

The easy chair is notable for the strong rake of its back and extraordinary evidence of its original upholstery. Though they were subsequently removed, remnants of the original upholstery were apparent in photographs taken around 1974 showing the chair in as-found condition. The photographs provided vital information for PMA’s technical examination of the chair, and between 2004 and 2005 PMA’s conservation department undertook significant examination of its structure, most notably by then Mellon Fellow Rian M. H. Duerenberg. The information revealed through her meticulous study has now been interpreted and translated into the stunning reupholstery program.

Fig. 2. Footboard valance from a full set of bed valances, probably Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, c. 1725–1750. Silk, buckram, wool, and linen; height 12 ½ inches. The decorative border is formed of two lengths of binding placed side by side, their inner edges overlapping in the center, to make the trim wider—and more visually effective—in a manner very similar to the binding on the wing panels of the armchair. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, gift of Ellen M. Stone; photograph courtesy of the museum.

A challenge for the project was reclaiming the significance of the extensive decorative brass nailing on the easy chair, nailing that is to be distinguished from the more functional nailing used to secure upholstery covers, particularly leather, to chair frames. The patterns indicate that the chair’s original covers—most likely of wool-and-worsted moreen—were supplemented by three different widths of silk-and-wool trim, a treatment previously suggested by only one other William and Mary easy chair, which is in the collection of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.3 Later Boston easy chairs with cabriole legs sometimes display polished steel nails about ¼ inch in diameter used to attach trim on the seat rails and other areas of the frame, and the frames of two rococo Boston easy chairs display extensive brass nailing patterns.4 The use such decorative nailing, however, is rare on American easy chairs, though it undoubtedly conformed to British usage. British seating with original upholstery often reflects royal or noble patronage, and typically the extravagant covers and silk trims on these pieces were applied without such decorative nailing.5 Based on other survivals, brass or polished steel nails were likely restricted to middle-class patronage: their chair covers were made of stout wool textiles, and trims were wool and silk rather than all silk.6

In the early 1700s decorative nails with cast-brass shanks and domed heads came in two standard diameters: 7/16 inch (the equivalent of the modern #10 or #10.5 nail) and 9/16 inch (the equivalent of the modern #9 nail). The brass nails on the PMA chair measure 7/16 inch, and while the shanks are often off center, they will be roughly 7/32 inch from the edge of the head. In examining a frame, the exact location of the shanks determines the possible location of decorative tapes. In period parlance, wider tapes—often used to bind edges on clothing or to cover seams or the end cut of fabric on upholstered furniture—were referred to as bindings. Narrower tapes, which were purely decorative, were generally referred to as braids and sometimes as lace.7 On the frame of the PMA’s easy chair, the decorative brass nails were spaced 1 ½ to 2 inches apart, not close-nailed or abutting.

Fig. 3a. Detail of the crest and wings of the chair in Fig. 1 before upholstery. The green dots on the un-upholstered frame indicate the original brass nail sites, which determined the placement of the bindings, braid, and brass nails for the re-upholstery project. Lengths of the 2-inch binding cross the inside and outside edges of the wings and nearly abut in the center of the wing panels.

Fig. 3b. Detail of the crest and wings of the chair in Fig. 1 after upholstery.

The front rail displayed two rows of nail sites that conform to its scalloped outline. They almost certainly correspond to the location of pleats for a binding that was 1 ⅜ inches wide—the width determined by the fact that the two rows of nail shank sites are 15/16 inches apart (Figs. 6, 7). On the side seat rails, rear rail, and the sides of the rear posts, the nail sites are 7/32 inch in from the edge of the frame. Since the nail heads measured 5/16; inch, the braid underneath them would almost certainly have been just slightly wider—about ½ inch across. On the rear posts, a 2-inch binding may have passed over the seam onto the rear face of the posts as well, but absent nail shanks there, we elected to use the ½-inch braid on the sides of the posts alone.

On the scrolled panel (or front face) of each arm, an outer row of nails was supplemented by four nails on the interior, suggesting a volute made with ½-inch braid. We realized that the nailing was probably confined to the upper portions of the arm panels because it ran off the tape where the edge rolls of the under-upholstery pushed the tapes away from the frame, or wooden stump. On the outside faces of the upper and lower arm scrolls, spaced nail sites indicated the location of ½-inch braid at the probable site of seams on the cover, a standard practice in upholstery of easy chairs and sofas of the 1700s. Further, these seams on the arm scrolls relate directly to the narrow (26 to 29 inches) width of the embossing rollers that created the pattern on the wool cover—the overall width of which would have been 28 to 32 inches between the selvedges.

Eaton Hill Textile Works in Marshfield, Vermont, wove the vermicelli-embossed moreen chosen for the PMA chair. The vibrant color we selected, thought to be what is referred to as crimson during the period, is documented on a later Boston easy chair.8 The design is based on an embossed wool-and-worsted moreen in the collection of the John Brown House Museum in Providence, Rhode Island.9 While initially appearing to be random, the design actually incorporates a pattern of two symmetrical cartouches. The repeat measures 44 ½ inches high by a horizontal width of 28 ½ inches—a critical detail because the dimensions of the pattern imposed the need to align the selvedges with the angle of the rear posts rather than on an absolute vertical. When the covers are applied in this manner, with the weft going “uphill,” the seams fall exactly on the location of the brass nailing of the outer arm scrolls (see Fig 3). A similar treatment is present on the silk covers of an early baroque English easy chair formerly at Chastleton House in Oxfordshire and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.10 But this is the first time this manner of applying inside and outside arm covers has been documented on an American-made early baroque chair frame, though only about half of the frames in the group have been examined for tacking or nailing evidence.

Fig. 4. The chair in condition as found by dealer John Walton in the early 1970s. Photographer unknown.

As noted above, the width of the ½-inch braid on the side seat rails and rear posts was determined by the location of the nail sites, which were about 7/32 inch inboard of the edges of the frame. On the wings and the crest, however, a series of nail sites was detected ½ inch inboard from the outer edge of the frame. These sites indicate that two lengths of 2-inch binding traversed, respectively, the seams on the inside and outside edges of the panels of the wings—as well as of the crest—and passed over cord sewn in those locations. While treatments with bindings trimming the inner and outer edges of panels on the wings have become a standard treatment of modern re-upholstery of baroque easy chairs, the 2-inch bindings on this example meet almost in the center of the panel.

Fig. 5. Detail of the crimson fabric woven by Eaton Hill Textile Works, Marshfield, Vermont, and trims used in the upholstery project. The 1/2-inch diamond braid reproduces trim on a Boston easy chair, c. 1740–1750, owned by the Colonel Daniel Putnam Association in Brooklyn, Connecticut; the 1 3/8-inch chevron binding by Context Weaving is based on an early eighteenth-century trim found at Hughenden Manor in England; the 2-inch binding is based on an early eighteenth-century sample surviving from the Hydes of Manchester.

The only known instance of two wide tapes abutting in this manner is found not on easy chairs, but on an extravagant, much-published bed valance in the Peabody Essex Museum (Fig. 2). Thus, the implication is that the similarly extravagant trim on the PMA easy chair was most likely intended to be en suite with that on bed hangings, window curtains, and a set of upholstered back stools. Indeed, extensive documentary evidence for this practice exists in probate inventories. For example, a 1746 auction at the house of Charles Paxton, Esq. of Boston included “A fashionable crimson Damask Furniture with Counterpain and two Sets of Window Curtains, and Vallans of the same Damask. Eight Walnut Tree Chairs, stuft Back and Seats covered with the same Damask, Eight crimson China Cases for ditto, one easy Chair and Cushion, same Damask, and Case for ditto.”11 But this is the first time that a comprehensive suite of bedroom furnishings can be corroborated by evidence on an extant easy chair frame.

Fig. 6. Side view of the frame of the chair in Fig. 1.

The PMA easy chair—like several others in the group—displays traits that disappear in later Boston easy chair frames. Most of the early examples are only 24 inches wide across the back; the back of the PMA easy chair is even narrower—measuring only 22 ⅝ inches. The width between the posts is just 19 ¾ inches, which means that, after the chair was stuffed, the sitter was confined within a surprisingly narrow space. Another feature shared by the early Boston easy chairs is the extreme layback, or the angle at which the back of the chair leans. Combined with having almost no heels on the rear feet, the large layback makes them susceptible to flipping backward and damaging their crest rails.12 On most of the chairs, the layback is about 12 inches, but on the PMA’s it is especially severe— 14 ½ inches—giving the chair a dramatic elegance.

While ample room exists for debate regarding the covers and trims we selected for this project, we believe our interpretation of the nailing evidence will provide a guide for future examinations of related easy chair frames.

Fig. 7. Chair seen in ¾ view from the rear. The ½-inch braid is applied with brass nails following the original irregular spacing on the frame.

For their assistance in the re-upholstery, the authors would like to thank Kate Smith and Justin Squizzero of Eaton Hill Textile Works, and Joseph P. Gromacki, Kurt Christian, Grant Cox III, Elizabeth Paolini, Mark Anderson, and Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III. We are also grateful to the Miller-Worley Fund for Excellence in Early American Art and the Women’s Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

ALEXANDRA A. KIRTLEY is the Montgomery-Garvan Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

ROBERT F. TRENT is a historic upholsterer and private consultant based in Wilmington, Delaware.

1 For an extended discussion on the chair and others in the group, see Robert F. Trent with Frederick Vogel III, Gerald W. R. Ward, Rian Deurenberg, Seated in Comfort: A Boston Easy Chair of 1710–1725 (Anne H. and Frederick Vogel III Collection of Decorative Art, Milwaukee, WI, 2016). 2 The Vogels responded to Walton based on his advertisement of the chair in The Magazine ANTIQUES in August 1981 (p. 4). At that time, Walton had reacquired it from collector Kenneth Milne, who had purchased it in 1974 after Walton advertised it in ANTIQUES in April 1974 (p. 4). 3 CW 1977-336, as discussed and illustrated in Leroy Graves, Early Seating Upholstery: Reading the Evidence (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA, 2015), pp. 44–47; and Robert F. Trent, “Boston Baroque Easy Chairs, 1705–1740” in American Furniture 2012, pp. 84–115, specifically p. 84, Fig. 1. 4 Trent, “Boston Baroque Easy Chairs,” pp. 103–106, Figs. 26, 27, 29, 30, and 32. See also Albert Sack, American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, vol. 2 (Highland House Publishers, Alexandria, VA, 1988), p. 381, no. 961; William Voss Elder III and Jayne E. Stokes et al., American Furniture 1680–1880 from the Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, 1987), pp. 52–54, cat. no. 34; Edward S. Cooke Jr., “The Nathan Low Easy Chair: High Quality Upholstery in Pre-Revolutionary Boston,” Maine Antique Digest, vol. 15, no. 11 (November 1987), pp. 1C–3C ; and Albert Sack, Fine Points of Furniture: Early American (Crown, New York, 1950), p. 65. 5 See Geoffrey Beard, Upholsterers & Interior Furnishing in England, 1530–1840 (Yale University Press, New Haven, for Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, 1997), p. 164, Fig. 118. 6 See Trent, “Boston Baroque Easy Chairs,” pp. 102– 104; Lucy Wood, The Upholstered Furniture in the Lady Lever Art Gallery (Yale University Press, New Haven, in association with the National Museums Liverpool, 2008), vol. I, pp. 3–95. See also Philadelphia Museum of Art acc. no. 1936-5-2, illustrated in Beard, Upholsterers & Interior Furnishing in England, p. 121, Fig. 73; and Morrison H. Heckscher, “18th-Century American Upholstery Techniques: Easy Chairs, Sofas, and Settees” in Upholstery in America & Europe from the Seventeenth Century to World War I, ed. Edward S. Cooke Jr. (W. W. Norton & Co., New York, 1987), pp. 97–111, esp. Figs. 85–94. 7 See the following references in Samuel Grant Daybook I, 1728–1737, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston: June 1728 reference to harateen (a synonym for wool-and-worsted moreen) bed with binding; August 1732 reference to binding and braid on a bed; April 1736 reference to lace for an easy cover; May 1736 reference for lace for curtains. Samuel Grant Daybook II: 1737–1766, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA: p. 379, 1743 reference to three window curtains with lace; p. 382, 1743 reference for lace for an easy chair loose cover; p. 438, 1744 reference to bed curtains with lace and braid. 8 The chair is illustrated in Trent, “Boston Baroque Easy Chairs,” pp. 103–109, Figs. 26–35. See also Adam Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture, 1715–1740 (Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2009) pp. 166, 167, Ps. 4:45, 4:46. Philadelphia inventories from the mid-1700s also include wool seating coverings in crimson. 9 Florence M. Montgomery, Textiles in America, 1650–1870 (W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1984), Fig, D-29, p. 198 10 The chair is Victoria and Albert Museum accession no. W.18-1973, collections.vam. ac.uk/item/O369943/armchair. For a side view of the chair, see Peter Thornton, “Upholstered Evidence: Or How the Members of the Furniture History Society Came to Assist in Saving the Remains of a Queen Anne Wing Chair,” Furniture History, vol. 10 (1974), pp. 17–19 and pls. 6a, b. On Boston “Queen Anne” chairs that retain their original foundations and covers, the upholsterers oriented the fabric of the inner wings/arms 90 degrees from the floor, resulting in the loss of a large V-shaped gore at the draw-through in the rear of the frame; as a result the covers are often seamed toward the front of the arm scroll. 11 Boston News-Letter, January 9, 1746, as cited in George Francis Dow, Everyday Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony p. 51, as cited in Montgomery, Textiles in America, p. 199. 12 The distance of the overhang of the back to the rear seat rail (or plumb line down from the crest rail and the distance to the rear) determines the layback.