Sofa table attributed to Isaac Vose and Son, 1819– 1822. Private collection; photograph by David Bohl, courtesy of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Boston.

Robert D. Mussey Jr.

and Clark Pearce, Rather Elegant Than Showy: The Classical Furniture of Isaac Vose (Massachusetts Historical Society in association with David R. Godine, 2018). 294 pp. Exhibition catalogue for Entrepreneurship and Classical Design in Boston’s South End: The Furniture of Thomas Seymour and Isaac Vose, 1815–1825, on view at the Massachusetts Historical Society through Sept. 14.

Monumental. Monumental—like the furniture itself—is the first word that comes to mind to describe both the scope and the achievement of the project documenting the life and art of cabinetmaker Isaac Vose (1767–1823), who led the furniture-making community in early nineteenth-century Boston. Furniture historian and conservator Robert D. Mussey Jr. and furniture historian, dealer, and adviser Clark Pearce joined forces about six years ago to consider the work of Vose as part of the collaborative project “Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture.” Mussey and Pearce uncovered documents at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and the City of Boston Archives, among other places, that linked Vose and his shop to a bevy of high-caliber furniture—both well known and hiding in plain sight. This monograph and the exhibition it accompanies are the culmination of a rehabilitation project of sorts. As Mussey points out in his introduction, when Vose-made heirloom furniture from the Channing and Parkman families was given to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in the 1950s, the pieces were quite nearly worthless, and Vose himself almost forgotten.

Born in the Massachusetts village of Milton, Vose trained with an as yet undocumented cabinetmaker, though the authors present evidence pointing to Charlestown’s Benjamin Frothingham (1734 –1809). Vose possessed an unusual mix of gifts: the skills of an outstanding cabinetmaker, along with stylistic pre-science and business acumen. He was the first to locate his shop in Boston’s South End, where he imported, processed, and sold mahogany as a commodity. He adapted his furniture designs to progressive tastes for a volumetric, pared-down classicism; his furniture “played up” to the quality of imported furniture. And he understood the furniture being made in his shop as just one part of a classical interior, expanding his repertoire and adding imported accoutrements to complement it.

Dressing table with mirror attributed to Isaac Vose and Son, 1819–1822. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Aimée and Rosamond Lamb; photograph © 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

An early 1790s commission from merchant Joseph Barrell for entire sets of furniture for several rooms—both in his town house and his country estate, the Charles Bulfinch–designed Pleasant Hill—characterizes the orders Vose received. To this reader, whose work has focused on Philadelphia and Maryland, where sideboard tables and sideboards appeared in the 1770s and 1780s, it was notable that Mussey declares Barrell’s June 1793 purchase of a sideboard as “one of the earliest known records in Boston of a form just being introduced from England.”

The English-trained cabinetmaker Joshua Coates appeared as a journeyman in the Vose shop on the 1797 tax rolls, three years after his arrival in Boston. He was the first immigrant hired by Vose, who realized the advantage of a talented craftsman familiar with the latest styles overseas. He allowed Coates to set the bar for taste and quality high, catapulting the business to the forefront of design, construction, shop organization, and innovation. In 1805 Coates joined Vose as partner, and their workshop became Boston’s undisputed ground zero for cabinetmaking. Vose and Coates made a practice of hiring the best immigrant talents, such as Thomas Seymour in 1819, and the accomplished English-trained woodcarver Thomas Wightman—of whom Mussey writes: “no immigrant contributed more to the growing sophistication of Vose & Coates’s furniture.”

The firm’s furniture epitomized Boston’s English-leaning interpretation of the rage for Grecian style—the all-encompassing term for a range of revival styles, from Egyptian and Etruscan to Greek and Roman. (An interesting side note: the Washington, DC, house of Charles Bagot, Britain’s ambassador from 1815 to 1819, was filled with furniture made by Vose and Coates of Boston. President Monroe imported furniture from France.) The litany of commissions from Boston’s mercantile elite sends the reader on a dazzling march through the range of the Vose firm’s furniture and the houses of the city’s wealthy—often multiple generations of the same families. The firm prospered as they consistently undertook large commissions with an open mind to the vicissitudes of style and taste.

Dressing bureau with mirror, with stenciled label of Isaac Vose and Son, 1820–1824. Private collection; photograph by Laura Wulf, courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

When identifying individual Vose pieces, the writers were fortunate to have a sizable group of documented furniture to begin with. From a trove of invoices and other substantiating material, they built more strong and sensible attributions. To me, the most exciting commission is described in the sixth chapter, where the reader is treated to a full explanation of the impressive purchase of furniture made by the city of Boston in anticipation of the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to the city in 1824—five years after Coates’s death and one year after Vose’s, when the firm was being run by Vose’s son Isaac Vose Jr. with Thomas Seymour still at the helm as foreman. The firm provided seventy-eight pieces of elegant furniture and various lighting that are detailed in forty-nine lines of an invoice discovered in the Aldermen’s Papers in the City of Boston Archives.

Pearce’s chapter on connoisseurship—aptly titled “By These Signs You Will Know Them . . .”—takes the curious reader beyond general descriptions of furniture and into the minutiae that impart an ability to identify furniture from the Vose firm. Furniture is directly connected to printed sources, and construction details and nuances are described and illustrated. For instance, the leafy acanthus collar on the pylon-shaped pillars of tables was carved separately, and from a solid piece of wood, and slides onto the pillar. Construction of the plinths of Vose pier tables includes a large dovetail connecting the rear rail to the side rail, rails that conform to the shape of the plinth, and glue blocks, while those of rival makers Emmons and Archibald “consistently employed long, narrow, rectangular recesses with no glue blocks.”

Unlike New York, Philadelphia, and Washington furniture makers, those in Boston did not publish a price book—essentially an index of forms maintained within the trade—that reflected stylistic practices and predispositions that had become conventional. Did this encourage creativity in Boston? Likely yes, and the authors contend that the Vose firm was forced to be creative within a conservative milieu. While I agree with that assessment, I do not consider Boston classical furniture conservative in its elegance, but, rather, I think Vose furniture is unfussy and restrained in its elegance. That is, however, subjective—and simply a matter of semantics.

Pier table, attributed to Vose, Coates, and Company, with carving by Thomas Wightman, 1817– 1819. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Kaufman Collection, promised gift of George M. and Linda H. Kaufman; photograph by Lee Ewing.

The book is organized in seven easily digestible sections and two appendices. Mussey wrote the first six, presenting a historiography of classical furniture in Boston and elsewhere, followed by lengthy, wonderfully contextualized biographies of Vose and members of his cabinetmaking shop, chief among them Coates, Seymour, Wightman, and the French-trained William Piquot. The appendices list the furniture documented to Isaac Vose and to the men who made the Vose shop tick: journeymen cabinetmakers, upholsterers, chair- makers, carvers, painters, sawyers, and clerks.

The impetus for the monograph and exhibition came not only from the authors, but also from Margaret Burke, former director of the Concord Museum and an accomplished furniture historian, and her husband, Dennis Fiori, the president emeritus of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The authors acknowledge a lengthy list of colleagues—among them Charles Buckley, Berry Tracy, Jonathan Fairbanks, Stuart Feld, Page Talbott, Jane Nylander, Richard Nylander, Wendy Cooper, and Donald Fennimore—whose work stoked their interest. The authors refreshingly note the contributions of early pickers and dealers, such as Hyman Grossman and Gary Kingsley, and, later, Carswell Rush Berlin. They express a debt to exhibitions such as Tracy’s Classical America, 1815–1845 (1963, Newark Museum); the Met’s Nineteenth-Century America (1970); Cooper’s Classical Taste in America, 1810–1840 (1993, Baltimore Museum of Art) and Classical Maryland, 1815–1845 (Maryland Historical Society, 1993); and even my own 2016 exhibition, Classical Splendor, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Most patently, this monograph follows in the footsteps of the work on Massachusetts makers John and Thomas Seymour (2003, by Mussey) and Nathan Lumbard (2018, co-written by Pearce) and New Yorkers Honoré Lannuier (1998, by Peter Kenny, et al.) and Duncan Phyfe (2011, by Peter Kenny, Michael Brown, et al.).

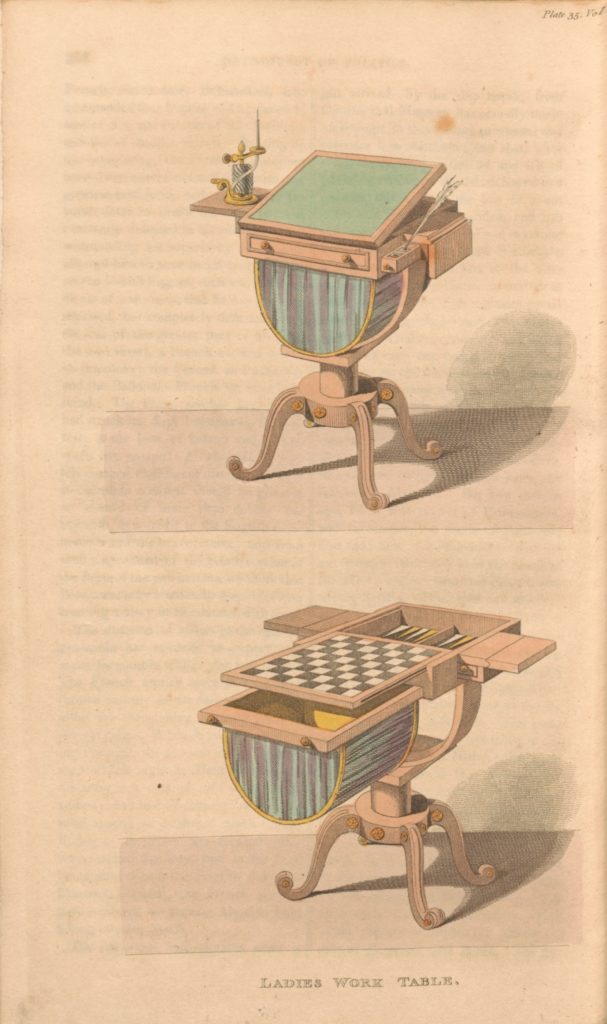

Metamorphic work-and-game table attributed to Isaac Vose and Son, with carving by Thomas Wightman, 1820–1824. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of William N. Banks and Mrs. Stanford Calderwood; photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Ladies Work Table from Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics, ser. 1. vol. 5 (June 1811). Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.

Mussey and Pearce have placed Vose and his coterie in context, strengthening my frequent refrain: successful American artisans of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries perceived themselves as participants on a world stage—and catered to their patrons’ similar view. The tenacity and focus required to undertake a study of this depth on Boston’s most prosperous and artistically successful furniture-making firm will hopefully serve as a clarion call and spawn similar studies on equally worthy makers throughout America—including several Philadelphia makers. Lavishly illustrated and with a design that itself is “rather elegant than showy,” this volume deserves much applause—and a spot in the library of collectors, scholars, and curators.

We who study the decorative arts of the past—particularly brown furniture—have been affecting a rather somber demeanor of late. I hear people go on and on about how interest is waning and “it’s not like it used to be.” Well, yes. But my question is, who wants to join our party if the refrain is that we are not doing well? I reject the notion that we are not thriving. An impressive roster of scholars, collectors, and dealers supported the exhibition and this magnificent volume; if it were a list of guests to a dinner party, it would surely make for a memorable evening! Like nearly every other industry and cultural pastime—from sports to the theater—the digital age has engendered tremendous change, change that has encouraged us to shift our tactics and presentation of interesting material—and prosper. Vose changed his tactics as tastes, expertise, and artisanal talent shifted. He prospered.