The brilliance of the master printmaker owed something to the patronage of Hollywood royalty but a great deal more to the dynamism of early California modernism.

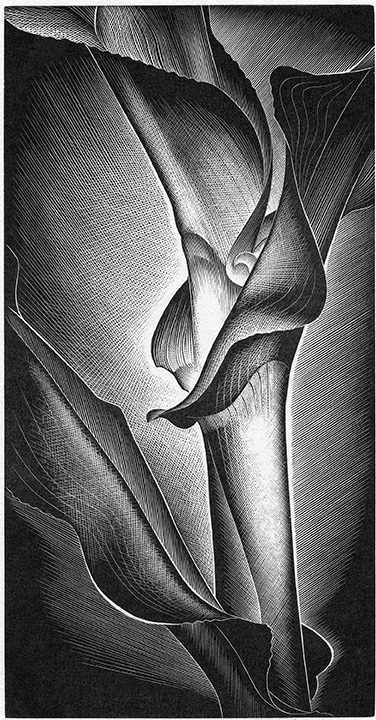

The cultural coming of age of early modern Los Angeles has been aptly described as a “small Renaissance, Southern California style.”1 The artist who may have best captured its spirit was Paul Landacre, a virtuosic draftsman and master printmaker whose métier was xylography, the art of wood engraving (Fig. 3). His prints featured rolling California hills, classically inspired nudes, and local architectural and natural wonders. Their stylistic eloquence and technical brilliance won accolades from curators and colleagues alike.2 Rockwell Kent, in a rare display of selfeffacement, acknowledged that Landacre was, without exception, the country’s finest wood engraver.3 John Taylor Arms, a leading figure in the graphic arts, described himself as a “flagrant admirer” of Landacre’s prints and contended that no survey or annual graphic exhibition in New York would be complete without a representation of his work.4 In 1947 the Smithsonian celebrated Landacre at midcareer by giving him a solo exhibition that was curated by painter and printmaker Jacob Kainen.

Landacre’s proximity to Hollywood—he and his wife lived in a rustic bungalow on a nearby hill—shaped much of his artistic life. Just as the silver screen created visions more beautiful, and at times more haunting, than reality, Landacre brought a world of spellbinding radiance into high relief. The velvety blacks and dazzling whites of his early prints, exemplified by Sapling Slim and Shadow Naked (Fig. 2), seduce with the glow of a motion-picture still. The addition of crosshatching to his crisply cut edges and fine lines harmonized well with modern fashion and set design.

The booming motion-picture industry also nurtured Landacre’s artistry in another, equally important, way. For several years during the Depression, Landacre secured the patronage of Hollywood royalty. Prosperous filmmakers and movie stars joined forces with local cultural and industrial elites to keep the artist afloat. In 1934 thirteen of them became founding members of the Paul Landacre Association and annually committed $100 each to purchase his new work.5 A force behind the association was Delmer Daves, a screenwriter and movie director whose devotion to Landacre’s art and economic well-being was virtually limitless. Daves used his Hollywood connections to bring Landacre patrons and commissions for the next thirty years. The earliest assignment may have been a wedding present for Daves’s friend, actor Lloyd Nolan, and his bride, actress Mary Elizabeth “Mell” Efird (Fig. 5). Landacre engraved a design that catches her stealing one final glance in the dressing room mirror before a performance. When Daves married a beautiful ingénue years later, Landacre captured her high hopes with stars glittering over a globe of worldly aspiration (Fig. 7).

The association liberated Landacre from the dictates of both the marketplace and the government-sponsored Public Works of Art Project. During its six-plus years he reached artistic maturity and produced a succession of award-winning prints that included such works as Growing Corn (Fig. 1), Storm, The Press (Fig. 4), Tuonela, Sultry Day, Coachella Valley, Dark Mountain, Death of a Forest, and August Seventh (Fig. 11). Although alluring, Landacre’s California imagery was not conceived as booster art to promote the natural splendors of the West. Instead, it offered a modern vision with innovative designs and exacting technique. In 1929 poet, bookseller, and gallerist Jake Zeitlin began showing Landacre’s prints and drawings alongside the work of other emerging West Coast artists.6 The exposure, Landacre’s earliest in a Southern California gallery, secured his artistic reputation and led to representation across the country. Consignments were soon solicited by the Dalzell Hatfield Gallery in the Ambassador Hotel—a high-end Los Angeles showcase for modern European and American masterworks. For the gallery’s proprietors Landacre engraved a sensual nude backgrounded by shimmering concave forms and cascading fireworks (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Mell Efird Bookplate, 1933. Wood engraving, 4 7/16 by 2 1/2; inches (image including lettering). Private collection.

Many Hollywood visitors to Zeitlin’s bookshop gallery were smitten by Landacre’s spare California desert scenes. Among them was John Van Druten, the budding English playwright now indelibly linked to the musical Cabaret. He ordered editions of Landacre’s wood engravings to affix to custom-made holiday cards in 1930 and 1931. A rare surviving example demonstrates how smartly the playwright informed recipients of his Hollywood aspirations (Fig. 10). Van Druten was particularly taken with the austere beauty of the Coachella Valley and the desert town of Indio (subjects Landacre engraved), where he eventually made his midlife retreat.7

Another early devotee of Landacre’s stylized landscapes was the actress Gloria Stuart. Before her Hollywood ascent she wrote a review of a group show at the avantgarde Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel and singled out Landacre’s wood engravings as the “three most interesting” on view. Monterey Hills (Fig. 9), she noted, cleverly employed the “device of a blackout in the lower corner” that “lets the eye travel over the intervening light spaces to the black outline of the top-most peaks.”8 The prints Stuart praised gained national recognition when they were included in California Hills and Other Wood Engravings by Paul Landacre, a bound folio of fifteen prints selected by the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) as one of the Fifty Books of the Year for 1931.

Fig. 6. Ruth and Dalzell Hatfield Bookplate, 1932- 33. Wood engraving, 5 9/16 by 4 inches (image). Private collection.

The Hollywood hills inspired one of Landacre’s better-known designs—George Cukor’s bookplate (Fig. 8).9 In 1936 Landacre visited the director’s home above the Sunset Strip, scene of legendary merrymaking, and created a pencil sketch he then transferred in reduced scale to a woodblock. In it he took the vantage point of one of Cukor’s swimsuited revelers; the rippling water denoted by the curvilinear wave pattern floats above the director’s engraved name.

The nearly one-ton nineteenth-century Washington Hand Press Landacre operated was his indispensable mechanical partner. By pulling its curved lever that acted on a toggle joint, he applied pressure to the rectangular metal plate, transferring the image from the inked woodblock to paper (Fig. 3).10 Because California lore identified Landacre’s press as one Mark Twain had used, Hollywood’s publicity machine sought it out to promote the film The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938).11 One studio photo op caught the artist in his ink-smudged work clothes showing the child actors how paper pulled from an inked woodblock replicates the engraved image—in reverse (Fig. 12). Their eyes study August Seventh (Fig. 11), an atmospheric composition the artist later submitted to the National Academy of Design as part of his diploma presentation.

The rusty printing press Landacre had painstakingly cleaned and restored became the subject of one of his most dynamic and sought-after prints: The Press, an American emblem of machine age modernity (Fig. 4). The sweeping design of clean lines and flowing geometrics conveys Landacre’s exhilaration about the laborious process of using it.

Landacre’s passion for music is evident in a series of twelve composer portraits he engraved as covers for the Los Angeles radio station KECA’s concert guides. Igor Stravinsky (Fig. 13) was the last of these. Stravinsky’s modernism electrified Southern California audiences after Otto Klemperer became music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in 1933. Ward Ritchie, who designed many of the books Landacre illustrated, marveled at the way Landacre “caught” Stravinsky’s “vibrant, piercing personality.”12

Thanks to Landacre, xylography had its Hollywood close-up. In the fall of 1944 RKO Pictures brought the artist to the set of its romantic feature film The Enchanted Cottage. The script united two glamorous stars, Dorothy McGuire as a wallflower whose avocation is wood engraving and Robert Young as a scarred war veteran.13 Their love for each other is mysteriously transformative—McGuire turns beautiful and Young handsome, but only to each other as newlyweds inside a peculiar cottage on the coast of Maine. RKO hired Landacre to instruct McGuire on the use of a graver. The woodblock Landacre engraved for her to handle in the movie is lost, but the impressions he pulled from it survive, and their beauty underscores his dedication to the project (Fig. 14).

In fact, for Landacre the cinematic encounter was cathartic. He identified with the physically challenged war veteran played by Young and was transported back in time to Ohio, where as a promising collegiate middle-distance runner he had almost died from a streptococcal infection and septicemia that left his right leg permanently stiffened.14 No doubt he also felt at home in the cottage, whose isolation and garden evoked the charm of the bungalow he shared with his wife. The Landacre home still stands. Its survival is a tribute to the art created there that is so closely linked with Hollywood in the heyday of the “small Renaissance, Southern California style.”

1 The phrase was coined by Jake Zeitlin (1902-1987), who personified the cultural energy of postwar Los Angeles and became the nexus for dozens of leading figures in the city’s history. For an excellent overview of the city’s artistic awakening, see “Naturally Modern,” the chapters written by Victoria Dailey in William Deverell, Michael Dawson, Victoria Dailey, and Natalie Shivers, LA’s Early Moderns: Art, Architecture, and Photography (Balcony Press, Los Angeles, 2003), pp. 17-115. 2 Arthur Millier, the lead art critic for the Los Angeles Times, praised equally the differing approaches Landacre took when rendering natural forms as opposed to manmade structures. See “Landacre strikes brilliantly, at his best, in either style,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1930. 3 Millier noted that “Rockwell Kent, who might well claim the spot for himself, has rated Landacre the country’s Number One [wood engraver].” See Arthur Millier, “The Arts and Artists: The Art Thrill of Last Week,” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1939, C7. 4 John Taylor Arms to Paul Landacre, January 27, 1943, Paul Landacre Archive, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA. 5 The founding members of the Landacre Association were Delmer Daves, Homer Crotty, W. B. Geissinger, M. S. Slocum, Ted Cook, Dr. A. Elmer Belt, Margaret “Peggy” (Mrs. E. C.) Converse, Richard W. Millar, Ruth (Mrs. Leslie M.) Maitland, Jacques Vinmont, Walle Merritt, Jake Zeitlin, and Carrie Estelle (Mrs. Edward L.) Doheny. By late 1937 eight more members had signed up: Frank Borzage, Ruth Chatterton, Kay Francis, Mrs. Samuel Goldwyn, Frederick G. Hall, John Halliday, and Mr. and Mrs. Karl Struss. 6 See Sonia Wolfson, “Among Our Younger Artists,” Game and Gossip, May 1929, p. 99. 7 The alluring nearby mountains, date palms around the house, and “star-hung and crystal-clear” nights of the California desert all brought the playwright happiness. See John Van Druten, The Widening Circle (William Heinemann, London, 1957), pp. 1, 44. 8 The Carmelite, vol. 4, no. 45 (January 7, 1932), p. 4 [mistakenly paginated as p. 6]. Photographs by Edward Weston and lithographs by Henrietta Shore were included in the exhibition. 9 Using thin beige Japanese laid paper, Landacre printed about fifteen impressions of the bookplate (sheet size 8 ¼ by 5 3/8 inches). Only two of them are signed. Small-scale line-cut reproductions of Landacre’s engraved bookplate were adhered to books in Cukor’s extensive library. In addition, a posthumous edition of the bookplate was produced and printed on white wove paper. 10 Landacre bequeathed the Washington Hand Press to one of his former students at what is today the Otis College of Art and Design, but it was dismantled and stolen before delivery was made. It resurfaced several years later and ultimately entered the collection of the International Printing Museum in Carson, California, where it is on prominent display. 11 In 1930 Landacre’s printing press was found by his friend Willard Morgan “in an old barn in the environs of the famous mining town of Bodie, California.” According to Morgan, the press had been “used in the local newspaper office.” See Willard D. Morgan, Our Columbian Press (Morgan Press, Scarsdale, N. Y., 1959), pp. 5-6 (copy in the Paul Landacre Archive). Twain, however, did little reporting and no printing during his three-month sojourn near Bodie during the winter of 1864-1865. Instead, he “spent most of his time loafing in a local saloon…listening to stories and jotting down notes for future reference.” Franklin Walker, San Francisco’s Literary Frontier (1939; University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1969), p. 193. 12 Ward Ritchie, introduction to Great Composers, From 12 Wood Engravings by Paul Landacre (Invierno Press, Northridge, Calif., 1981). 13 The screenplay altered Arthur Wing Pinero’s 1921 three-act play, in which the female protagonist does needlework. Delmer Daves was probably responsible for the script change, which gained Landacre the considerable wartime fee of $685, according to his account books in the Paul Landacre Archive.14 Landacre was deeply moved by McGuire’s performance in the movie. Referencing his own courtship, he wrote her that “the story” of the two lovers in The Enchanted Cottage “came close to our own early experience.” Paul Landacre to Dorothy McGuire, annotated typescript dated December 9, 1944, Paul Landacre Archive.

JAKE MILGRAM WIEN, an independent curator and historian, is the author of the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Paul Landacre’s prints, drawings, and paintings.

Fig. 1. Growing Corn by Paul Landacre (1893–1963), 1938. Wood engraving, 8 3/4 by 4 1/2 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 1. Growing Corn by Paul Landacre (1893–1963), 1938. Wood engraving, 8 3/4 by 4 1/2 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 2. Sapling Slim and Shadow Naked, 1928. Wood engraving, 8 by 5 7/8 inches (image). Private collection. All works by Paul Landacre © The Paul Landacre Estate/VAGA, New York, NY.

Fig. 2. Sapling Slim and Shadow Naked, 1928. Wood engraving, 8 by 5 7/8 inches (image). Private collection. All works by Paul Landacre © The Paul Landacre Estate/VAGA, New York, NY. Fig. 3. Landacre in his studio pulling the lever of his nineteenth-century Washington Hand Press, c. 1937. Gelatin silver print. Private collection.

Fig. 3. Landacre in his studio pulling the lever of his nineteenth-century Washington Hand Press, c. 1937. Gelatin silver print. Private collection. Fig. 4. The Press, 1934. Wood engraving, 8 5/16 by 8 5/16 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 4. The Press, 1934. Wood engraving, 8 5/16 by 8 5/16 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 7. Mary Lou Lender Daves Bookplate, 1939. Wood engraving, 3 9/16 by 2 1/4 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 7. Mary Lou Lender Daves Bookplate, 1939. Wood engraving, 3 9/16 by 2 1/4 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 8. George Cukor Bookplate, 1937. Wood engraving, 5 7/16 by 3 11/16 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 8. George Cukor Bookplate, 1937. Wood engraving, 5 7/16 by 3 11/16 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 9. Monterey Hills, 1930. Wood engraving, 5 7/8 by 7 7/8 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 9. Monterey Hills, 1930. Wood engraving, 5 7/8 by 7 7/8 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 10. Desert Dawn, 1931. Wood engraving, 2 13/16 by 3 11/16 inches (image). Signed and numbered, and affixed to a holiday card sent by John Van Druten. Private collection.

Fig. 10. Desert Dawn, 1931. Wood engraving, 2 13/16 by 3 11/16 inches (image). Signed and numbered, and affixed to a holiday card sent by John Van Druten. Private collection. Fig. 11. August Seventh, 1936. Wood engraving, 12 1/16 by 8 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 11. August Seventh, 1936. Wood engraving, 12 1/16 by 8 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 12. Landacre in studio work clothes showing Ann Gillis and Tommy Kelly (respectively cast as Becky Thatcher and Tom Sawyer in the 1938 film The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) the engraved woodblock for, and a matted impression of, August Seventh, c. 1938. Gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 by 8 3/4 inches. Private collection.

Fig. 12. Landacre in studio work clothes showing Ann Gillis and Tommy Kelly (respectively cast as Becky Thatcher and Tom Sawyer in the 1938 film The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) the engraved woodblock for, and a matted impression of, August Seventh, c. 1938. Gelatin silver print, 6 1/2 by 8 3/4 inches. Private collection. Fig. 13. Igor Stravinsky, 1935–1936. Wood engraving, 6 3/4 by 4 5/8 inches. Private collection.

Fig. 13. Igor Stravinsky, 1935–1936. Wood engraving, 6 3/4 by 4 5/8 inches. Private collection. Fig. 14. The Enchanted Cottage, 1944. Wood engraving, 5 3/4 by 7 15/16 inches (image). Private collection.

Fig. 14. The Enchanted Cottage, 1944. Wood engraving, 5 3/4 by 7 15/16 inches (image). Private collection. Fig. 15. Dorothy McGuire simulating the engraving of a woodblock at her worktable in The Enchanted Cottage (1944). Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 by 7 3/4 inches. Private collection.

Fig. 15. Dorothy McGuire simulating the engraving of a woodblock at her worktable in The Enchanted Cottage (1944). Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 by 7 3/4 inches. Private collection.