Best known for her electroplated metal sculptures embellished with richly colored enamels, June Schwarcz produced an extensive body of work in her sixty-year career that, while linked to long-standing vessel-making traditions, defied convention. Many of her vases and bowls were different because, as she wryly noted, “They simply don’t hold water.”

Born June Theresa Morris in Denver, Schwarcz was the great-granddaughter of one of the first Jewish settlers in western Colorado. Reared in a tradition-bound household, she was taught the practical domestic skills women were expected to learn to prepare for marriage and family life. Among these were sewing and tailoring, including the use of patterns to plan and construct dresses and other clothes. Later in life she formulated an inventive approach to metalwork using these techniques to make solid, freestanding forms.

After studying writing at other colleges, Schwarcz switched to art and design when she attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn between 1939 and 1941. She spent several years working in fashion and packaging design, and married Leroy Schwarcz, a mechanical engineer, in 1943. With their two children, the family would move several times—and as far afield as Brazil—over the next decade and a half before settling permanently in 1958 in the Bay Area town of Sausalito.

Schwarcz had been introduced to enameling four years earlier while visiting family in Denver. A friend there had taken a course in enameling, and Schwarcz sat rapt as the friend and three other enamelists discussed the craft and the different techniques and processes used in the medium. Soon after, with Kenneth Bates’s 1951 book Enameling: Principles and Practices as her guide, Schwarcz began to enamel herself. As a largely self-taught enamelist, she was unencumbered by orthodox approaches to process. In her work of the 1950s and early 1960s, she advanced a modernist aesthetic. Her unusual approach to basse-taille enameling and her use of an abstract visual vocabulary gained widespread recognition and established her as an innovative leader in the enamels field.

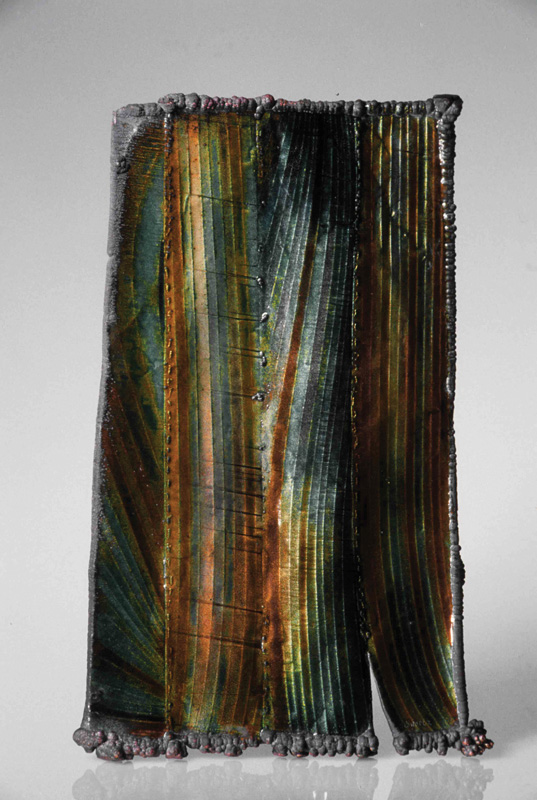

Basse-taille, a French term meaning “low cut,” is an enameling technique that traditionally involves cutting, engraving, or acid etching a metal plate or vessel to create a relief design. Once transparent enamel is applied to the metal, the design in the substrate is visible through layered veils of color. From her earliest explorations of enameling, Schwarcz was attracted to basse-taille because of the way in which light reflects off the underlying metal and interacts with the enamel’s color. With unbridled enthusiasm for this versatile medium, she cut, gouged, scraped, chased, and etched the surface of her copper plates and plaques and then applied and fired numerous layers of translucent enamel. Schwarcz’s work in basse-taille was idiosyncratic, improvisatory, and highly experimental. These became the defining characteristics of the work she produced over the next sixty years.

In the early 1960s, wanting to create unique sculptural objects, she devised a new way of building forms in metal using electroplating. The audacious body of work she produced at this time combined the raw, protean properties of metal with the luminosity of glass in a richly evocative mix.

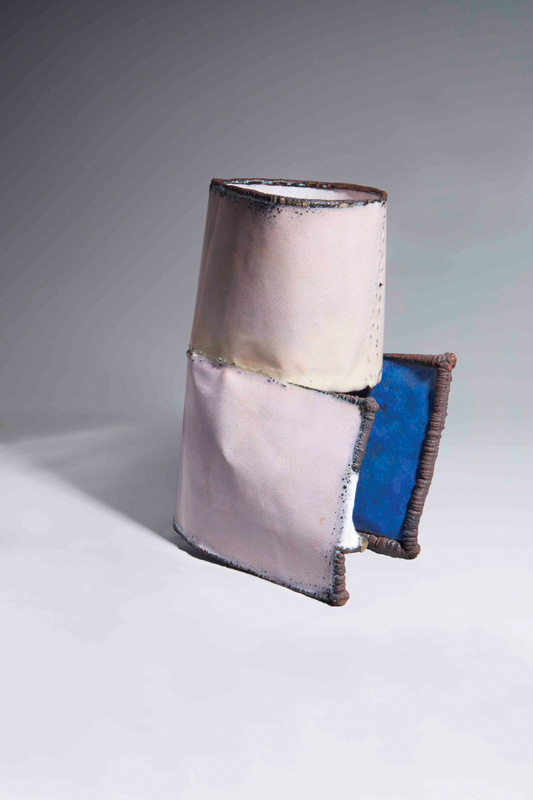

By the late 1960s, continuing her experiments with plating, she developed an ingenious method of constructing freestanding forms in metal using sewing techniques she had learned as a child. Stitching together thin sheets of copper prior to plating, she produced a wide array of forms that she subsequently enameled. This breakthrough led to further explorations of form and content and an abiding commitment to experimentation throughout her long and distinguished career.

June Schwarcz was a mild-mannered iconoclast, a gentle rule breaker. She created forms that were at once raw and elemental, yet elegantly composed and lushly beautiful. Committed to abstraction, she found common cause with artists outside her own field. In her home she surrounded herself with work by the artists she admired—prints by Robert Motherwell and Ellsworth Kelly, furniture by Marcel Breuer and Arthur Espenet Carpenter, and sculptural objects by her Bay Area friends and colleagues Kay Sekimachi, Bob Stocksdale, Lillian Elliott, Dominic Di Mare, and others. Drawn to diversity, she found resonant cultural linkages in simple objects made for daily use. She collected and was inspired by art and design from a variety of cultures, including African sculpture, Oceanic carvings, and Japanese art. A voracious reader and an enthusiastic museum visitor, she also sought inspiration in the history of art and in the work of artists ranging from Albrecht Dürer to Paul Klee and Mark Rothko.

Schwarcz was recognized early in her career as a fresh new talent in her field. In 1956, just two years after she began to work in enamel, she was included in Craftsmanship in a Changing World, the inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York. She was also featured in that museum’s seminal 1959 exhibition Enamels and the watershed traveling exhibition Objects: USA, a showcase for the nation’s studio artists and artisans that opened in 1969.

As her reputation grew, she was increasingly singled out as one of the most progressive figures in enameling. In 1964 she appeared in a two-person show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and in 1965 she was given a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts. June Schwarcz: Forty Years/Forty Pieces, organized in 1998 for national tour by the San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, represented one of the crowning achievements of her professional career. The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s 2017 exhibition June Schwarcz: Invention and Variation, presented at the Renwick Gallery two years after her death, solidified her reputation as one of the leaders in the late twentieth-century enamels field.

Enamel—glass fused to metal through a high-temperature firing process—is a versatile medium with rich artistic traditions. Its most familiar formats range from dazzling jewelry and small sculptural forms to vessels, ecclesiastical objects, and wall-mounted plaques and panels. The techniques enamelists use to apply powdered glass to metal have varied greatly over time. While some enamelists continue to use such established techniques as cloisonné, champlevé, or plique-à-jour, others explore uncharted territory, discovering new ways to unleash their medium’s full expressive potential. The work of June Schwarcz falls squarely within this second tradition.

In a field known for visual opulence, preciousness, and adherence to traditional craft practices, Schwarcz was a renegade. She learned enameling on her own and adopted a highly experimental approach to process, inventing new ways of creating forms in metal and new strategies for their embellishment.

1 In conversation with the authors, June 5, 2014. 2 “A Picturesque and Lovable Figure Has Passed in the Death Today of M. Strouse,” Grand Junction Daily Sentinel, November 1, 1928.

BERNARD N. JAZZAR and HAROLD B. NELSON founded the nonprofit Enamel Arts Foundation in 2007 to support and promote the modern and contemporary enamels field. Jazzar is curator for the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Collection in Los Angeles; until his retirement in 2017, Nelson was curator of American decorative arts at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. They are the authors of June Schwarcz: Artist in Glass and Metal (ACC Art Books, 2019).