“Without doubt, the first visit was the most astonishing and moving experience in the arts that I have had,” wrote the late Ruth DeYoung Kohler, longtime director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center (JMKAC) in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, about exploring Eugene Von Bruenchenhein’s Milwaukee home in 1983, shortly after the artist’s death. “The Von Bruenchenhein home was painted inside and out in large shapes of vibrant colors. The tiny foyer was stacked floor to ceiling with Kentucky Fried Chicken boxes filled with chicken bones from a nearby restaurant’s refuse—all to be used for Eugene’s exotic thrones and towers. . . . Seeing the immensity and power of Eugene’s output left me forgetting to breathe.” The house was deteriorating—it couldn’t be saved.

And so, a new mission presented itself to JMKAC, founded in 1967, which had theretofore limited itself to temporary exhibitions as well as preserving art environments in situ: to become a collecting institution. That it did, and with July’s inauguration of the Art Preserve, a $40 million, fifty-thousand-square-foot showcase—situated on the outskirts of Sheboygan—for the environments collected by JMKAC over the last forty years, all those carefully preserved houses, apartments, sheds, and sculpture gardens now have a permanent home of their own.

We don’t usually think that a piece of art works only if it’s surrounded by the trappings of the studio from which it came, though maybe we ought to. Artist Ray Yoshida, instructor of several of the painters known as the Chicago imagists while at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—and whose apartment has been re-created on the third floor of the Art Preserve— “taught his students that objects had a life, and were affected by what was around them,” JMKAC’s curator Laura Bickford notes.

What goes for works of art goes for the institutions that hold them, too, in this case the world’s first museum devoted to artist-built environments. A manufacturing and dairy town of fifty thousand situated some 130 miles up the coast of Lake Michigan from Chicago may seem like a less-than-ideal setting for an institution intent on winning converts to a totally new way of thinking about art. But if a commitment to providing context is at the heart of the Art Preserve’s mission, then it could hardly have been anywhere else. Seven of the twelve artists whose work is given substantial airing at the Art Preserve hailed from or spent part of their lives in either Wisconsin itself or the Midwest in general (the Kohler family’s eponymous enamelware business is also based in the area, up the Sheboygan River in the village of Kohler), and the geography and history of the region serve as useful entry points to the seemingly self-contained environments on view.

Take Albert Zahn. Born in the Prussian province of Pomerania on the Baltic Sea, Zahn settled in the dramatic karst landscape of the Door Peninsula in northern Wisconsin around 1880. Formed from a stony ridge called the Niagara Escarpment, the same rock formation that the famous falls tumble over in upstate New York, the area’s dunes, cliffs, and deep forests make it a tourist destination today, as well as a haven for migratory and nesting birds. An 1831 treaty with the Menominees, which also surrendered the land Sheboygan now stands upon, made it one of the first areas in Wisconsin available to loggers. Unlike many immigrants from Europe, much of which had long been deforested, those from Germany, with its partly intact virgin timber, preserved the woodlore of their ancestors. This can be seen in the wood-based arts of the Pennsylvania Dutch or the Moravians in South Carolina, and in the work of Zahn in Wisconsin. Settling and farming in Bailey’s Harbor, Zahn in his free time took to whittling likenesses of the forest and riparian birds he encountered—bald eagles, cardinals, red-headed woodpeckers—using the straight-grained wood of oldgrowth white cedars, some perhaps a millennium old, whose stumps riddled the property he shared with his wife, Louise, and their nine children. Painted by Louise, the sculptures adorned the family’s concrete-block house, the facade of which has been re-created at the Art Preserve.

Another distinguishing aspect of artists’ environments in the Upper Midwest, as Bickford points out, is that they’re often assembled from multiple components. “It’s cold in Wisconsin, and you might have been assembling in your garage during the winter,” she says. Such working methods are conducive to the creation of sculpture gardens and architectural ornamentation, like that of Mary Nohl, whose summer house in the beach community of Fox Point north of Milwaukee is surrounded by a collection of colorful characters cast out of concrete. A graduate of Chicago’s Art Institute, where she received instruction from Grant Wood and Rockwell Kent, and took Helen Gardner’s art history class, Nohl was an artistic polyglot, taking inspiration from sources as diverse as Louise Nevelson, Sam Rodia (creator of the Watts Towers in Los Angeles), and her own brother, a famous deep sea diver and explorer of Lake Michigan, and turning it into paintings, mobiles, and cartoons. The quiet beach community in which she lived from 1948 to her death in 2001 was less receptive to her freewheeling creativity. Her property was repeatedly vandalized (hence the concrete—initially Nohl made her outdoor sculptures out of wood, which neighborhood scamps set afire) and received the epithet “the Witch’s House.” Debate between the Art Preserve (which stewards the property) and local residents about what to do with the house, on the National Register of Historic Places since 2005, rages on to this day. The exhibit at the Art Preserve, which includes an exterior wall from Nohl’s beach-side building, as well as a suite of her lysergic paintings, serves as an introduction to Nohl’s work while the alpha and omega of it remains closed to the public at Fox Point.

The importance of sui generis siting was no less important to the Art Preserve’s architects, Denver-based Tres Birds—who served as planners, architects, and exhibition designers for the project—than it was for many of the environment builders. Constructed mainly out of glass and concrete aggregate made with local river rock, the building is nestled into a bluff at the northern edge of the Sheboygan River floodplain. Soaring glulam timber “shades” at the entrance evoke the beech-dominated primordial forest that sheltered generations of Algonquin- and Sioux-speaking Native Americans along the coast of Lake Michigan, and then the settlers who came by packet across the lakes. The shades are one of many sustainability-minded engineering choices that also include motion-activated lights and geo-stabilized heating and cooling. The environmentalist concern also receives literal embodiment in such inspired elements as a ground-floor bathroom tiled with hundreds of images of endangered plants from east-central Wisconsin by artist Beth Lipman, the subject of a current retrospective at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York.

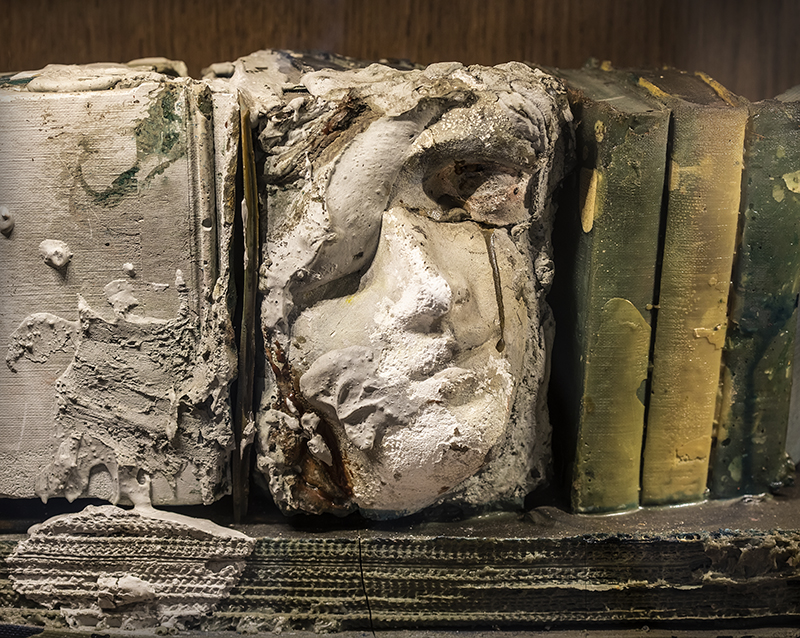

Of course, the Midwest isn’t the only regional setting that gave rise to artists’ environments. New York City is represented by Stella Waitzkin, whose Chelsea Hotel apartment with its “Lost Library” of resin-cast books is installed on the second floor of the building, as well as textile artist Lenore Tawney, whose Soho loft-slash-studio is likewise re-created. Looking farther afield, the Art Preserve is also the stateside repository for the work of Indian artist Nek Chand. One of ten million Sikhs and Hindus who in 1947 fled from the newly created Pakistan to India, Chand became a roads inspector in Le Corbusier’s planned city of Chandigarh. Seeing the potential in an unused slice of rolling, brush-covered terrain, Chand erected an eighteen-acre sculpture garden complex populated with figures from his lost Pakistani homeland. The Art Preserve holds dozens of Chand’s sculptures, which are displayed on a sinuous terraced platform made from an armature covered with spray-on concrete that evokes the earthworks still standing in India.

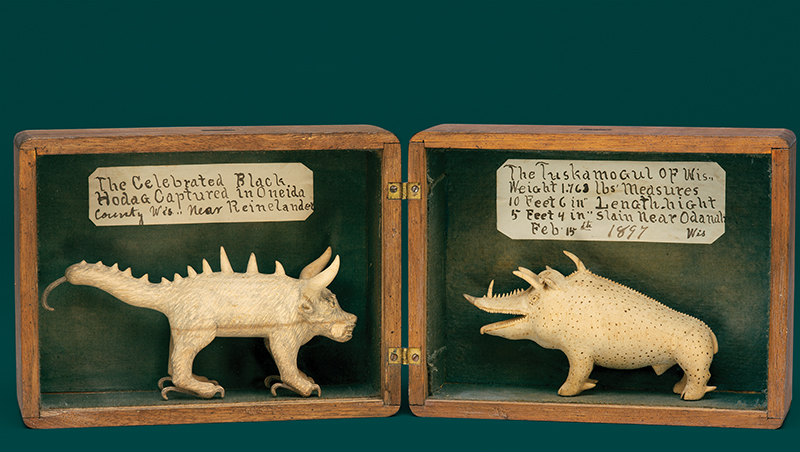

There are three types of exhibits at the Art Preserve. The first type is designed as an adjunct to a site that still exists, such as Nohl’s or Chand’s. Second is tableau re-creations—such as that devoted to woodcarver and showman Levi Fisher Ames, whose “L. F. Ames Museum of Art” is set up next to a small stage on the ground floor, on which contemporary artists will perform responses to his work. And third is open storage, which is devoted to the likes of sculptor Charles Smith from Augusta, Illinois, and painter Gregory Van Maanen. The absence of the spaces that weren’t able to be saved or transported in toto, such as Yoshida’s, Waitzkin’s, and of course, Chand’s (you can’t very well transport an entire earthwork into a museum; besides, it’s the second most popular attraction in India), is palpable. The preserve’s curators have compensated as best they can, sometimes to haunting effect. Pristine white walls matching the footprint of Von Bruenchenhein’s house stand in for that structure, his brightly-painted sculptures displayed in vitrines instead of on the shelves, tables, and wood floors they were originally strewn across.

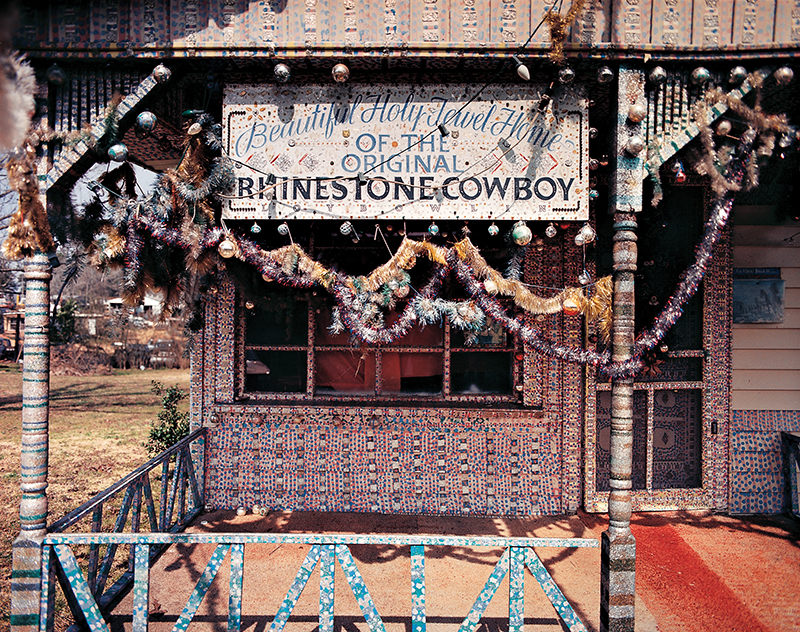

One wishes that, perhaps, the Art Preserve were somehow a bit messier—despite its chaotic architecture comprising jutting walls and bays, it’s as clean-lined and pristine as any of the dozens of concrete temples to art erected over the last few decades, and so enormous it appears in danger of swallowing up even the stipple-covered house of Loy Bowlin, which is here in its entirety. Yet the institutional setting serves its purpose by foregrounding the art, and makes viscerally apparent why the environments’ creators gravitated to the warmth of wood, or to shining metal or ceramic.

On the top floor, whose windows look out across the 143-acre Willow Creek Preserve, recently purchased from the city of Sheboygan using funds made available by factories that befouled the Sheboygan River with industrial waste, is the Art Preserve’s showstopper: Emery Blagdon’s Healing Machine. A loner and ardent amateur scientist, Blagdon had been deeply affected by the early deaths, from cancer, of both his parents. Suffering from arthritis himself, he prowled the estate sales around his Nebraska Sandhills property looking for old TVs and radios, metallic ribbons, copper wire and batteries. From these he constructed what was meant to serve as a gentler version of electroshock therapy, a shed-sized device to collect and concentrate the magnetic fields generated by mobiles of wire, beer cans tin-snipped into the shape of flowers, and other showy metal elements artfully framed against humbler wood and wax paper, and conduct them into the sufferer. The faith Blagdon had in his machine was considerable: during his own fight with the cancer that would eventually kill him, going inside the machine was apparently the only treatment he received. The entire shed is here—if you go inside, you might forget you’re in a museum and dream you’re in the sandhills, your troubles gently being washed away by this overwhelming work of art.