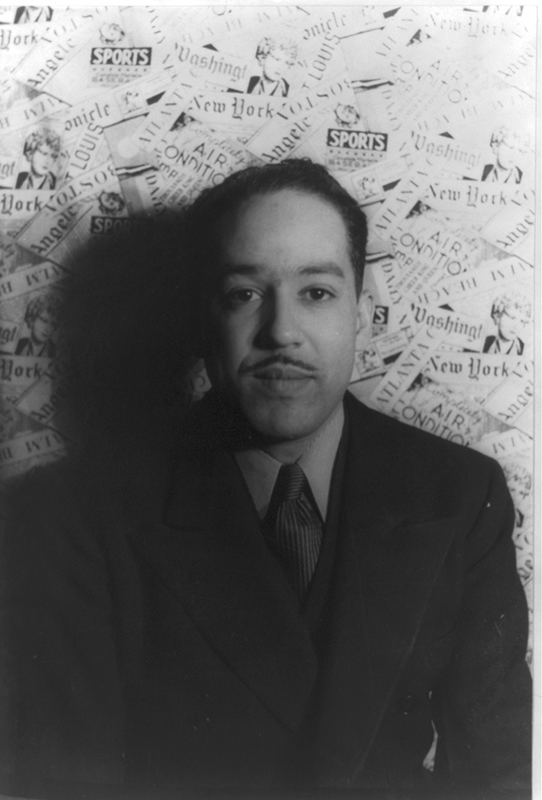

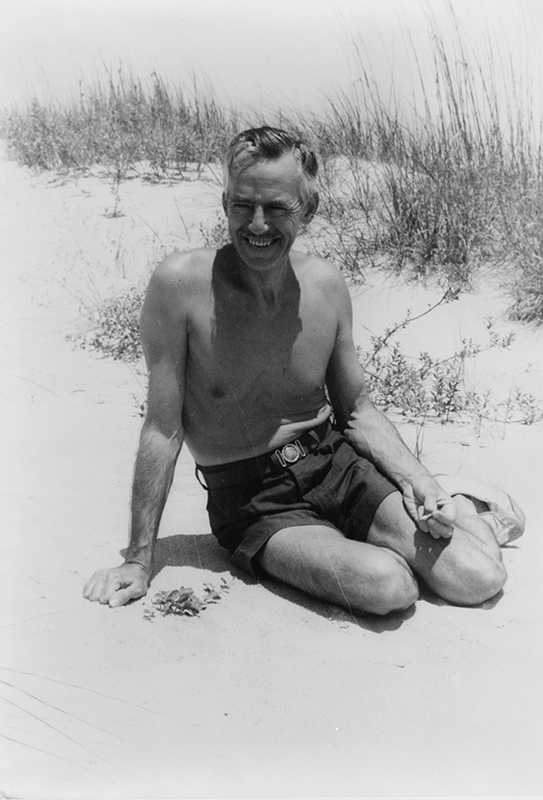

Fig. 2. Portrait of Langston Hughes [c. 1902–1967], 1936.

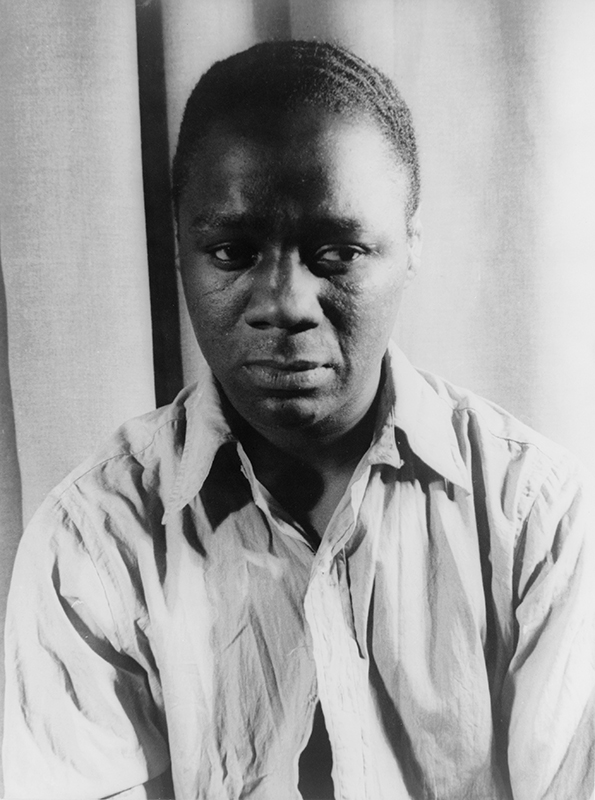

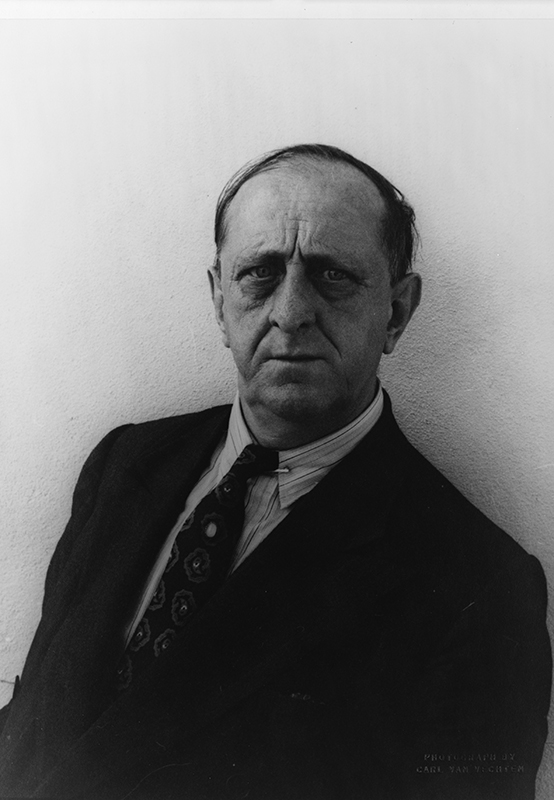

Fig. 3. Portrait of Ethel Waters [1896–1977], 1938.

Long before celebrity was quite what it is today, capturing the faces of the accomplished— whether for the private enjoyment of the sitter, for public exhibition, or as illustrations for newspapers and, later, magazines— has been central to photographic practice. Years before he chronicled the carnage of the Civil War, Mathew Brady was shooting the likes of Thomas Cole, John James Audubon, and Daniel Webster. Beginning in 1910, Alfred Stieglitz turned his lens on his own circle—Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Arthur Dove, among others. By the time Henry Luce’s Life landed on coffee tables in 1936, the celebrity image was a staple of our visual culture.

The roster of photographers whose portraits comprise a pantheon of the twentieth century’s leading artists and intellects includes Yousuf Karsh, Arnold Newman, George Hurrell, Cecil Beaton, and Philippe Halsman. Arguably less well known today is writer and critic Carl Van Vechten, a son of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, who emerged as something of a celebrity photographer in the New York City of the 1920s (Fig. 4). He shot a range of individuals, from established talents—Ethel Barrymore, Theodore Dreiser—to rising stars such as Aaron Copland and Orson Welles (Fig. 8). As Carl Van Vechten: Man about Town—an exhibition on view at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art—suggests, it seemed no one of note escaped his attention.

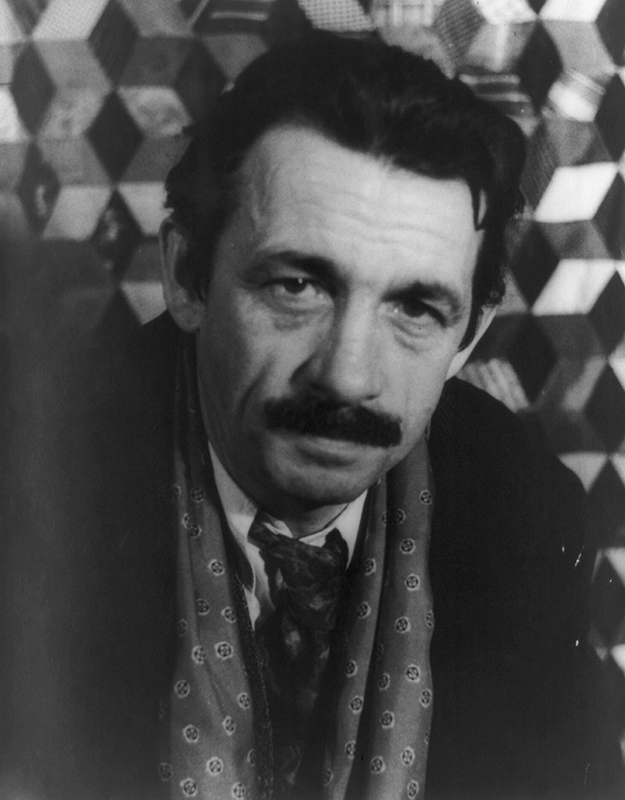

Fig. 5. Portrait of Diego Rivera [1886–1957], 1932.

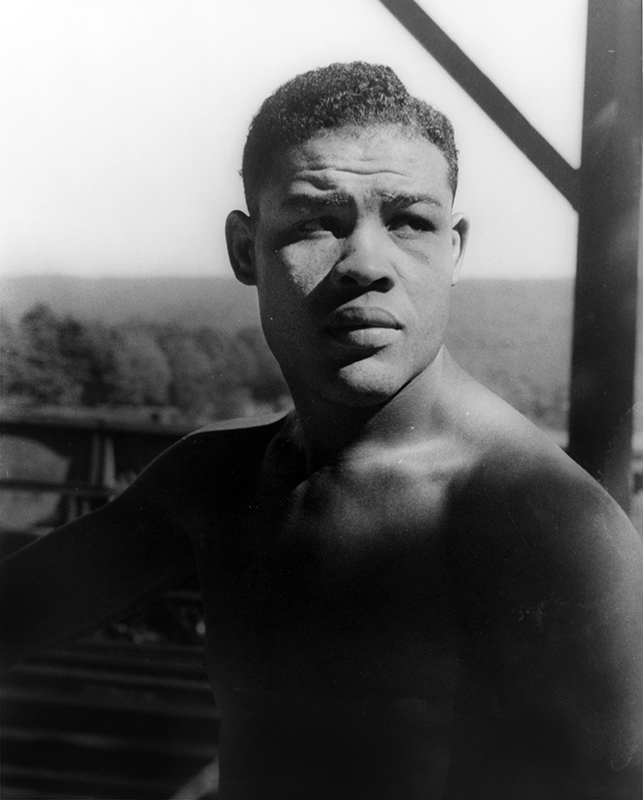

Fig. 6. Portrait of Canada Lee [1907–1952], in Native Son, 1941.

Van Vechten began his career as a journalist, filing crime stories and light society pieces for the Chicago American. After moving to New York in 1906, he was hired by the New York Times and soon named assistant to the paper’s music critic. Within a couple years, he added dance and theater criticism to his portfolio (the latter as a staffer at the New York Press). In 1915 he published his first collection of critical essays; in 1922 Alfred A. Knopf issued his first novel, Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works.

Fig. 8. Portrait of Orson Welles [1915–1985], 1937.

Fig. 9. Portrait of Thomas Benton [1889–1975], 1935.

It wasn’t until 1932 that Van Vechten (reportedly at the suggestion of Mexican painter and muralist Miguel Covarrubias) bought a Leica and focused on the world he knew so well. His earliest work includes portraits of Sherwood Anderson, Tallulah Bankhead, Gertrude Stein (Fig. 7), Willa Cather, and Thomas Hart Benton (Fig. 9). Active through the early 1960s, Van Vechten went on to photograph a plethora of cultural stars, from Alexander Calder and Lotte Lenya to Harry Belafonte, Norman Mailer (Fig. 16), Marlon Brando (Fig. 15), Gore Vidal, and Edward Albee.

But he is best remembered as a promoter of the artists and other luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance. Van Vechten was indefatigable in championing such individuals as writer and NAACP leader James Wheldon Johnson; poet Langston Hughes (Fig. 2), whom he introduced to publisher Alfred Knopf; and singer Bessie Smith. He had demonstrated a curiosity about African American life in his Chicago days, and began to explore the landscape above 110th Street in the 1920s, years before he picked up a camera. In 1926 he published a novel, N****r Heaven, the repugnant title of which was but one of the book’s offenses. Intended as a revelatory celebration of Black life, it struck some critics of color as a superficial, nightlife-driven melodrama. W. E. B. Du Bois asserted that the book lacked “a single lovable character” and “scarcely a generous impulse or a single beautiful idea.”* (White critics and readers were more receptive and the book became a bestseller).

Fig. 11. Portrait of Paul Robeson [1898–1976], 1933. Gelatin silver print, 13 7/8 by 10 7/8 inches.

Fig. 12. Portrait of Edna St. Vincent Millay [1892–1950], 1933. Gelatin silver print, 13 7/8 by 11 inches.

Despite this seemingly grievous misstep, Black artists, some of whom had become part of the photographer’s social set, sat for him in the 1930s, including Cab Calloway (Fig. 1), Paul Robeson (Fig. 11), and Ethel Waters (Fig. 3). By today’s standards, Van Vechten’s efforts might be deemed paternalistic or an unseemly example of cultural voyeurism—a cosmopolite on safari rather than a true comrade in arms. Ambitious and fiercely attentive to his brand, Van Vechten must have understood his uptown images as a good career move—a niche to call his own—no matter how genuine his interest in his subjects. Although his initial impulse may have been exploitive, his careerlong interest in African American subjects suggests a more authentic engagement.

Fig. 14. Portrait of Marsden Hartley [1877–1943], 1939.

Fig. 15. Portrait of Marlon Brando [1924–2004], in A Streetcar Named Desire, 1948.

No matter whom he photographed, Van Vechten exercised an almost documentary approach. While he often placed his sitters before dynamically patterned backdrops, his images rarely manifest a significant concern with formalism. His lighting, too, was often less than artful, but when he shot writers, in particular, he made an effort to model their faces with shadows, most notably in his rendering of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (Fig. 12). And although some of his subjects strike a pose, or are positioned dramatically in profile, it is the snapshot-like quality (veering on the photo booth), the not-quite-ready for their close-up aspect of the pictures that generates a singular liveliness and immediacy.

Drawn from a gift the photographer made to the Cedar Rapids Community School District in 1946 and a subsequent bequest from his estate, Man about Town is a reminder of how big a role the portrait once played in creating public personae and how the bookish and brainy were not excluded from the spotlight. While not every one of today’s celebrities is a musician, actor, or athlete (think Jordan Petersen, Margaret Atwood, Steven Pinker), most recognized names of our time have gained fame via television or the internet. And for the most part, it seems that contemporary portraits are more about style, and more about the photographer’s signature or the sitter’s brand, than about truly probing the personality before the camera. The images Van Vechten produced may have been the result of random luck rather than keen observation, but looking at his portrait of welterweight-turned-actor Canada Lee, for example, one can believe that one is encountering a moment not entirely tailored for effect (Fig. 6). It’s an illusion of course. But isn’t that the essence of art?

Fig. 17. Portrait of Marian Anderson [1897–1993], 1940.

* W. E. B. Du Bois, manuscript (MS312) for a book review published in The Crisis, vol. 32 (December 1926), pp. 81–82, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

THOMAS CONNORS is a Chicago-based arts writer.

Carl Van Vechten: Man about Town is on view at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art through May 15.