Back in the 1970s, when I was a student at the Manhattan School of Music, I used to walk past Joan Briton’s antiques shop on the Upper East Side every weekend without fail. If you watch the 1971 movie The French Connection, in the scene where Gene Hackman is going into the Westbury Hotel, on Madison Avenue, the shop is to the immediate right of the lobby entrance. The gate was always pulled down—it never seemed to be open—but the window display was always charming, usually a chair, some artfully arranged fabric, a candelabra, and a piece of art. Not an interior setting, though, more of a tableau. On one of my excursions, the window had a white-painted Louis XVI medallion-back fauteuil covered with a dark green silk velvet, probably by Tassinari and Chatel, and I really wanted to buy it. Nobody ever answered the phone. So I sent a note and never heard back. I just kept calling, and one day, Joan’s daughter, Celine, answered the phone. “Oh, yes, yes, thank you for writing,” she told me. “Miss Briton hasn’t had the time to get back to you.” Well, I made an appointment to see the chair, bringing my checkbook, and after I arrived I asked the price, because nothing in the shop was marked. “But wait a minute, we don’t know anything about you,” Joan said, which I thought was so charming. We sat down, they asked where I was from (Philadelphia), how I got interested in French furniture (by visiting the Wrightsman Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art so often), and thus began a friendship of many years that also turned out to be important in shaping my taste.

Joan dealt in FFF, fine French furniture: Louis XIV, XV, and XVI, maybe some Directoire, maybe some Consulat, but that was it. Nothing earlier, nothing later, and nothing provençal. Hers was a very Parisian taste, though most of the furniture she sold had been found at châteaux in the French countryside, and she had an innate sense of how to live comfortably and beautifully. That being said, she was completely self-taught, came from Missouri, spent part of her early life as an amateur singer, and I doubt spoke any French. It’s hard to imagine an American chanteuse-turned-designer/antiquaire from Kansas City building the life she did. But then I started out in music and ended up in design, too, so perhaps it’s not so strange. The shop was small, about fourteen feet wide by thirty-two feet deep, with one room for the public—I don’t remember anybody ever coming in—and a little office in the back. Wedgwood-blue damask lined the walls above a white-painted dado. Furniture came and went, but there was always a Régence canapé set at an angle, and Joan and Celine, who served as a sort of secretary, sat on the canapé together, both wearing blond wigs and fur hats, a Pekingese perched on each of their laps. They were totally School of Gabor and spoke as if they had been trained in 1930s Hollywood. I remember Celine once saying to me, “Michael, I know you’ll appreciate this: to-mah-to is the perfect color.” They also presented themselves to the world as sisters, which was certainly strange, because Joan had been born in 1899 and Celine in 1919; furthermore, their real first names were Gladys. This all sounds humorous, but it’s really not. I loved them, I learned a lot from them, and they took an enormous interest in me—I was young enough to be Joan’s grandchild—telling me endless, endless stories, about summer buying trips to France, visits to private châteaux, and how they cut the tags out of their new couture dresses to avoid paying customs duties. There used to be a series of volumes that Hachette published, all in black-and-white, exploring châteaux all over France, and every Christmas Joan and Celine would give me one. I pored over those books, and as I did, I could see very much how they learned, because so much of what they liked was presented in those volumes.

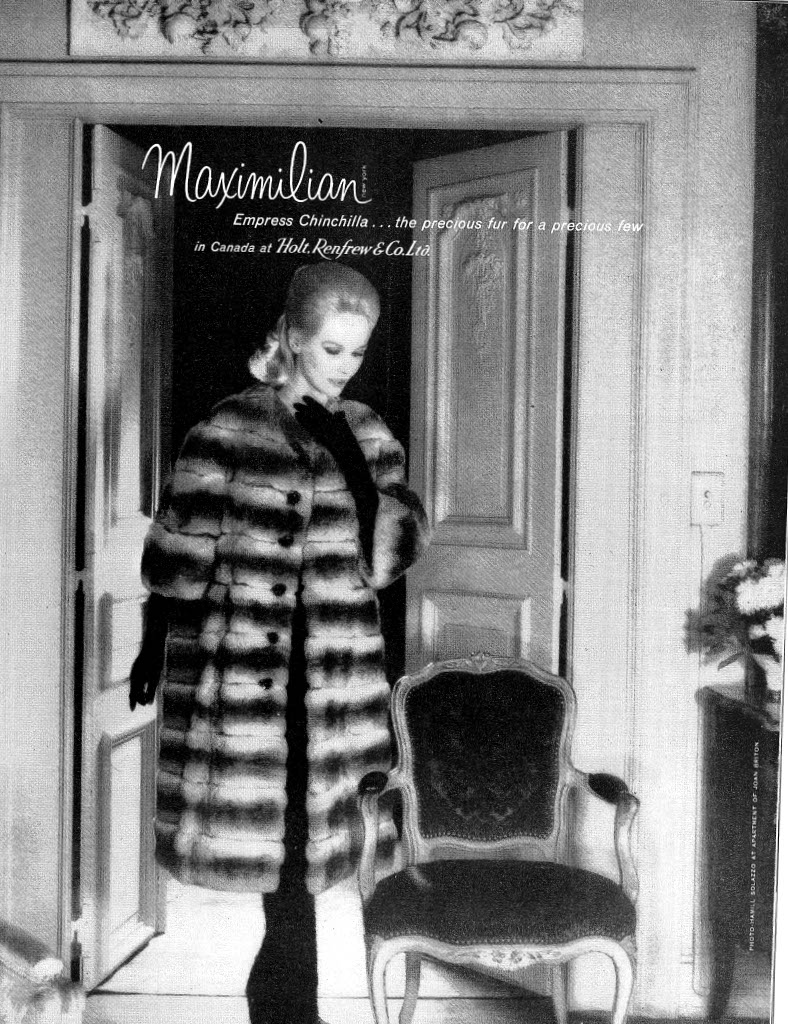

Nobody knows anything about Joan today, because she didn’t promote herself, though she did have a robust business. She was very low-key, but she knew where to go, who to work for, and what she was doing. She was keenly aware of textiles, trims, the finish on a painted table, how important a commode was or, conversely, how not important it was. She loved terra-cotta bas reliefs, and at her apartment the walls were hung with lots of them, and her taste in paintings was Le Prince, Boucher, and Huet. She also had two Louis XVI giltwood dog beds, one for each Pekingese, stamped by Jacob or maybe it was Sené. The Paris dealer Bernard Steinetz, who hired Celine as his Manhattan directrice after her mother died, called the apartment pure Versailles, which it was not, though it was beautiful. Through conversations with Joan, it became clear to me the importance of marrying the proper textile and the proper gimp or cord with a piece of furniture that was being upholstered. Guido De Angelis, the Manhattan custom studio, did all her upholstery and curtains, and much of the fabric she used came from her friend Franco Scalamandré; Joan was his all-time best client. What I liked about her work is that it was dressy, formal but not fancy. I think it’s fair to say that because of her, I have spent the better part of my career trying to get people not to go for the overly precious and overly ornamented, because there’s a fine line, a real distinct line, between what has integrity and natural beauty and what has less.