David Netto was probably destined to write Rosario Candela and the New York Apartment: 1927–1937 (Rizzoli, $85). The interior designer and historian has been studying the Manhattan architect’s work for decades, sparked by a childhood spent on the Upper East Side, surrounded by Candela structures. “My father was interested in real estate and used to buy and sell apartments,” he says, “so we would take long walks studying the facades of the best buildings.” Candela was the subject of an unpublished book that Netto wrote as a freshman at Sarah Lawrence College. After attending Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and studying architectural history at Columbia University, Netto opened his business in 2000, yet Candela seemed to always be stalking him. In 2001 the designer contributed a Candela essay to architectural historian Andrew Alpern’s acclaimed New York Apartment Houses of Rosario Candela and James Carpenter (Acanthus Press), and, he adds, “my father paid for rights for Alpern to make prints from the old glass negatives” of the subjects’ buildings.

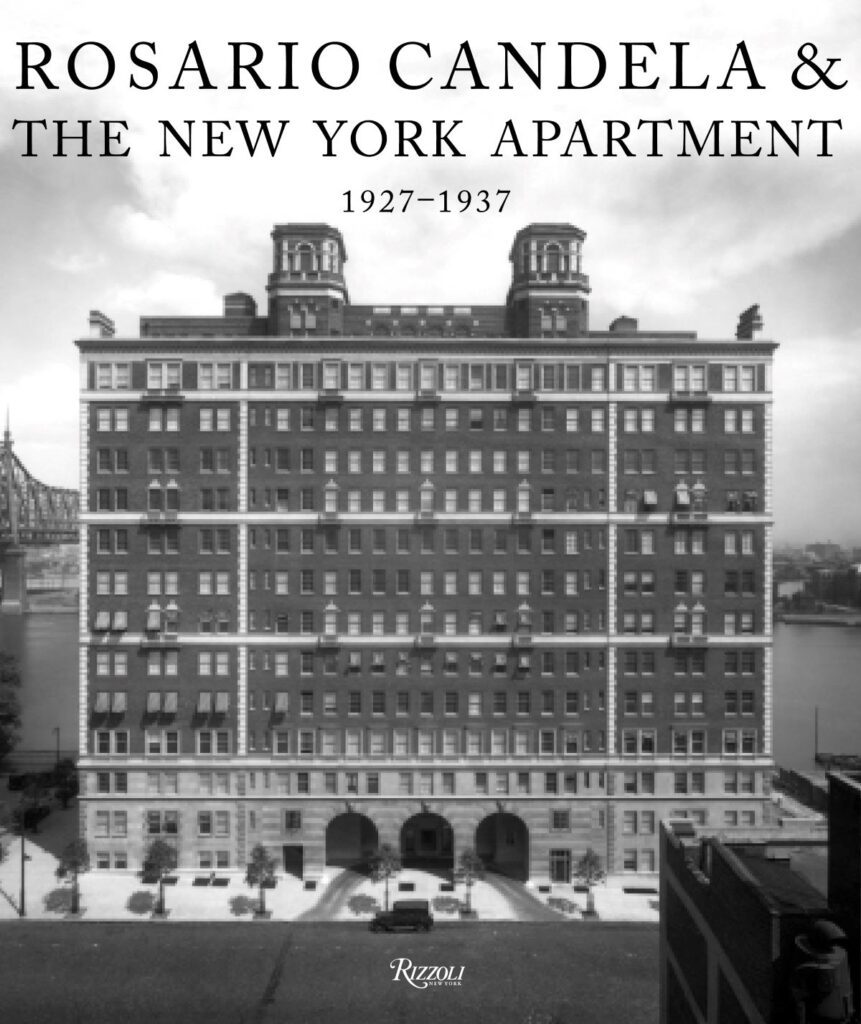

Netto’s new book offers a very personal take on Candela (1890–1953), plus the floor plans of his crown jewels, culled from the essential though very little read Select Register of Apartment House Plans: eighteen deluxe apartment buildings on Fifth and Park Avenues and Sutton Place, once home to residents such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Brooke Astor, Gianni Agnelli, Sunny von Bülow, and Anne Bass. Candela’s high-rise apartment houses, the best of which were erected during the period covered by the book, were steel-framed and masonry clad, graced with terraced setbacks (usually on the twelfth floor) and penthouses crowned with towers that were said to recall the palazzi of Candela’s native Sicily. Netto says those details give the roofscapes a sense of “voluptuousness.”

The book’s aim is to decode Candela’s genius. By studying the floor plans, Netto discovered that the architect not only knew how to divide an apartment into discrete areas for entertaining, service, and personal life, but also how to ensure the owner’s privacy, so servants could work discreetly. Family rooms were carefully separated from the kitchen, pantry, staff quarters, and service elevator. At 960 Fifth Avenue, which Netto calls the finest of Candela’s projects—he designed it with Warren and Wetmore, of Grand Central Terminal fame—visitors would enter a generous central foyer from the elevator vestibule. The foyer led to the public rooms: drawing room, library, and dining room. While serving drinks in the drawing room, the staff prepared the dining room. During dinner, the staff cleared the drawing room, so guests could then retreat to the library for coffee and cordials.

Two of Netto’s friends contributed essays: architecture critic Paul Goldberger and classical architect Peter Pennoyer. The former believes that Candela was “perhaps the greatest designer of apartment houses who ever lived.” They “exude not just wealth and grandeur but certainty,” he adds. “It is an architecture of self-assurance” for the “quiet rich.” An unanswered mystery is how the son of a plasterer learned how the rich wanted to live. He came to America in 1909, as a teenager, and though he studied beaux arts architecture at Columbia, Candela was neither elegant nor socially ambitious, but short and stocky, with a bristly crewcut.

“There was a disconnect between Candela’s personality and the buildings he produced,” admits Netto. Nonetheless, the designer thinks he found the clue to his subject’s romantic imagination. “Candela was an accomplished cryptographer who wrote two books on the subject and even taught courses in cryptology at Hunter College during World War II. I think he was interested in design from the problem-solving aspect. His passion was devising how to deliver beautiful spaces given the practical demands of the task. He was taking adversity and turning it into opportunity.”