“What distinguished the particular patriotism of the jubilee year . . . was a people’s sense of their extended range. They felt growth. They charted a physical expansion that seemed to them never-ending.” —Len Travers, Celebrating the Fourth (1997)

July 4, 1826, was an especially significant day in American history, marking the fiftieth anniversary, or “Jubilee,” of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and also the death of two of the nation’s most formative leaders, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. Largely unaware of this poignant coincidence, celebrations took place across the country in the form of parades, public orations, and readings of the Declaration. There were also newspaper essays, religious observations, and considerable drinking, dancing, and merriment, all in the name of patriotism. Amongst the largest events was the grand parade that marched past President John Quincy Adams and Vice President John C. Calhoun outside the White House, followed by a grand dinner and impressive fireworks display.

By 1826 the annual rite of celebrating the Fourth of July was already a well-established tradition, one that encouraged Americans to look to both the past and the future. In 1824, the nation had enthusiastically welcomed the return of the Marquis de Lafayette, the heroic French ally of George Washington during the Revolutionary War. A patriotic mindset had also led Congress, in 1817, to commission the famed painter John Trumbull to re-create a massive twelve-by-eighteen-foot version of his Declaration of Independence, one of a series of four history paintings to be placed in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol. His original version, only twenty-one by thirty-one inches, was begun in 1786 but not fully completed until thirty years later because of his desire to record the proper likenesses of the participants. In preparing the composition, which to this day is presumed to depict the actual signing of the Declaration, Trumbull initially gathered as much factual information as he could, even going so far as to interview Thomas Jefferson in Paris in 1786 about his recollections of the historic event.

Nevertheless, the artist did take historical and artistic liberties. As historian Emily Sneff has documented, the Committee of Five—John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut— is shown in front of the main table presenting the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock, in his capacity as president of the Continental Congress. In fact, this event occurred on the twenty-eighth of June, and did not include Franklin or Livingston, who was an unwavering opponent of the Declaration. The document was formally adopted on July fourth, but not actually signed by most members until after August second. In short, the gathering as painted by Trumbull, quickly embedded into the national consciousness, never actually took place, at least not as shown. The painter exercised similar artistic license in his depiction of the room itself, showing a classically inspired space that features a monumental ornamental trophy on the rear wall. Trumbull also added elaborate neoclassical chairs of the sort he would have seen in Europe in the early 1780s instead of the more modest seating, likely Windsor chairs, that occupied the Assembly Room. Perhaps in response to subsequent criticism regarding the inaccuracies in his original painting, he composed a more architecturally accurate version in 1832 (now in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art).

Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence, along with the other canvases in his Revolutionary War series, was formally installed in the Rotunda in 1826, just in time for the Jubilee. They were typical of the patriotic zeal of the moment, but also the tendency toward partial and idealized recollection. Commemorative expressions of this sort—whether in the form of grand historical paintings, moving public orations, or national days of celebration—are invariably veiled and incomplete, avoiding certain inconvenient and even tragic realities about America. This missing perspective is directly addressed in the lyrics for “No John Trumbull,” the opening song from an early workshop version of the popular 2015 play Hamilton:

You ever see a painting by John Trumbull?

Founding Fathers in a line, looking all humble

Patiently waiting to sign a declaration and start a nation

No sign of disagreement, not one grumble

The reality is messier and richer, kids

The reality is not a pretty picture, kids

Every cabinet meeting is a full-on rumble

What you’re about to witness is no John Trumbull

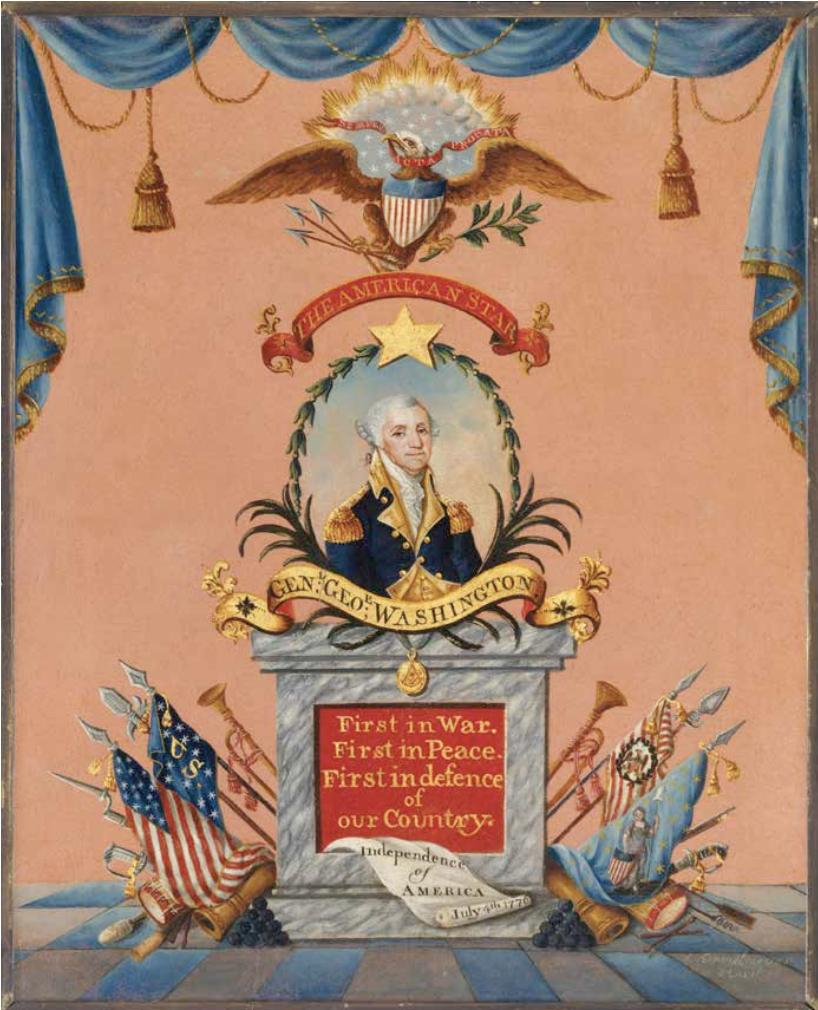

America had evolved into a powerful but complicated nation by 1826, one that is still recognizable today, with familiar cultural, racial, political, geographic, class, and commercial factionalization. The desire to celebrate the events of the Revolution steered many citizens toward a widespread sense of nostalgia—particularly those who had prospered in the blossoming democracy. In comparison to later national anniversaries, there was relatively little commemorative material culture, paintings, or even prints made for the occasion; commemoration happened largely through ephemeral celebrations. By broadening the conventional historical gaze, however, it is possible to find objects and images made before, during, and after 1826, which can be seen as part of a larger commemorative ethos.

Take, for example, a Grecian style window seat—one of a pair—that bears the signature of Duncan Phyfe, the famed New York furnituremaker. Also, on the underside of on one of the original surviving tufted seat cushions there is a pencil inscription with the date “July 4, 1826” where it would never have been seen once upholstered. Whether the stylish window seats were actually finished or sold on this day, or simply marked in honor of the anniversary, is unclear; but an intended patriotic meaning of the inscription seems quite likely. More expressly, Phyfe’s bold classical styling of this window seat form would have been understood to be an aesthetic expression of a broader American goal, that of both reviving and even improving upon the cultural glories of ancient Greece and Rome.

Another object that marked the Jubilee, literally, is the American silver half dollar. Although minted in various forms from 1807 to 1836, the “Capped Bust” coinage of the United States would have been symbolically potent in 1826. The figure was designed by John Reich, assistant engraver of the United States Mint in Philadelphia. Born in Bavaria in 1767, Reich arrived in America in 1800 as an indentured servant, by which time he had trained under his father, Johann Christian Reich, who specialized in the production of commemorative medals.

The personification of Liberty on the coin owes much to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. The Coinage Act of 1792 established the dollar as the nation’s currency and funded the creation of the United States Mint in Philadelphia. The legislation also stipulated that coins should bear the image of the sitting president, but this idea was rejected by Washington because of its monarchical implications. Jefferson, just back from serving as ambassador to France, suggested an Americanized interpretation of the French allegorical figure of Liberty, known in that country as “Marianne,” who wore the famed Phrygian cap symbolically associated with the French Revolution. Such allusions would have resonated powerfully in 1826, as would the inclusion of the Great Seal eagle on the reverse and the thirteen stars in honor of the original colonies, along with the words “United States of America” and “E Pluribus Unum”.

A well-known series of jacquard coverlets made between the early 1820s and the 1840s specifically celebrates the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. One example dated “July 4, 1826” was made for “Betsey Hayt,” and also features the name of General Lafayette. These visually powerful coverlets were widely manufactured and available in blue and white or red, blue, and white. Most feature double-tulip medallions ornamenting the central panel, framed by a range of motifs. Many feature a repeat of a spired building surrounded on either side by Masonic paired columns—Boaz and Jachin from the Temple of Solomon, symbols of God’s grace and strength—and a corresponding repeat of the Great Seal eagle. Several other design variations are recorded, including some that curiously include monkeys. Related coverlets feature distinctive corner panels that celebrate American industry, with the phrase “AGRICULTURE & MANUFACTURES ARE THE FOUNDATION OF OUR INDEPENDENCE” as well as the date “July 4” followed by a specific year—mostly from the 1820s into the 1840s. Complicating matters of attribution is the fact that during the colonial revival era in the early twentieth century variations of this coverlet design were replicated in great quantities.

The words on the coverlets can be understood in a number of ways. The term “AGRICULTURE” obviously boasts of the success of American farming but inescapably brings to mind the actual materials used to make the blankets—cotton and wool—inextricably associated at this time with the labor of enslaved human beings. This unacknowledged divergence of sentiment and reality also relates to “MANUFACTURING.” This proud boast about the nation’s rising infrastructure and factory system pays no heed to the social, racial, and gender conflicts that beset that process. In the context of the coverlets, the word is also self-referential: this type of double-sided weaving was only possible thanks to an innovative and efficient Jacquard loom. Guiding the warp and weft threads through a punched card (akin to those used on early computers) made such patterning easily replicable. Patterns could be purchased from suppliers in most major American cities, hence the widespread production. Clients and factory owners alike were also able to customize the design with the addition of their names, initials, and dates.

A final object linked to the Jubilee circles back to Lafayette’s triumphant return to America in 1824. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, was only nineteen years old when he first met George Washington in 1777; he went on to help defeat the British forces before returning to France and later played a key role in the French Revolution. It was President James Monroe who invited the heroic general to come back to America, a visit that turned into a thirteen-month-long tour across much of the country. The Marquis was accompanied by his son, George Washington de Lafayette. After visiting towns and cities all along the Atlantic coast, where large crowds cheered the legendary figure, Lafayette and his entourage traveled as far as New Orleans, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Nashville before finishing up in Washington DC. On the journey home, in September of 1825, he sailed past Mount Vernon.

As the last surviving general from the Revolutionary War, Lafayette was a central figure in the enthusiasm leading up to the American Jubilee. His portrait and the image of his arrival by ship at Castle Garden (now Castle Clinton) in Battery Park, New York, appears on prints from the era, as well as on ceramics and other decorative arts objects. Amongst the more colorful of these are the commemorative pitchers showing Lafayette’s landing that were skillfully crafted by the American Pottery Manufacturing Company, which was founded in 1824 and produced the earliest refined molded earthenware in this country. While this new process reduced the need for as many traditionally skilled potters, the company did retain a number of talented British-born artisans, including the modeler Daniel Greatbatch. He served as the master mold designer for the manufactory from 1838 to 1843, and may well have been directly involved with the design and production of the transfer-print decorated pitcher. That these pitchers were not made until the early 1840s further attests to the lingering sentiments associated with the national celebrations from two decades earlier.

The Jubilee is justifiably remembered as a highly significant patriotic moment. But as the historian Len Travers notes in his history of the earliest Fourth of July celebrations, 1826 also needs to be understood as a time of increasing conflict. Underneath the collective sense of nostalgia and patriotism, American identity was beginning to be challenged by a variety of troubling issues and events—including rapid geographic expansion and increasingly combative sectional divisions. The 1826 Jubilee and the 1876 Centennial were bookends of the Civil War era, in which the country was torn apart. This casts a retrospective shadow on the relatively small number of material culture artifacts linked to the Jubilee; meant to celebrate the nation, they largely turn away from its defining complexities. This dualism is woven to this day into all July Fourth commemorations, in which national pride is counterbalanced by people’s lived experiences.

JONATHAN PROWN is executive director and chief curator of the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.