The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 was America’s coming-of-age party. In celebrating the one hundredth anniversary of the signing of Declaration of Independence, the fair had twin goals: first, to celebrate a century of freedom; and second, to show the world how far America had progressed, from a rural, agricultural nation to a grand industrialized country that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Formally titled the International Exhibition of Art, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine, the fair welcomed contributions from thirty-eight countries in America’s first “official” world’s fair. More than 190 buildings spread across its approximately 230-acre site in Fairmount Park. The American exhibits were meant to illustrate how national ideals, perseverance, and innovation had produced a level of technological prowess equal to that of Europe.

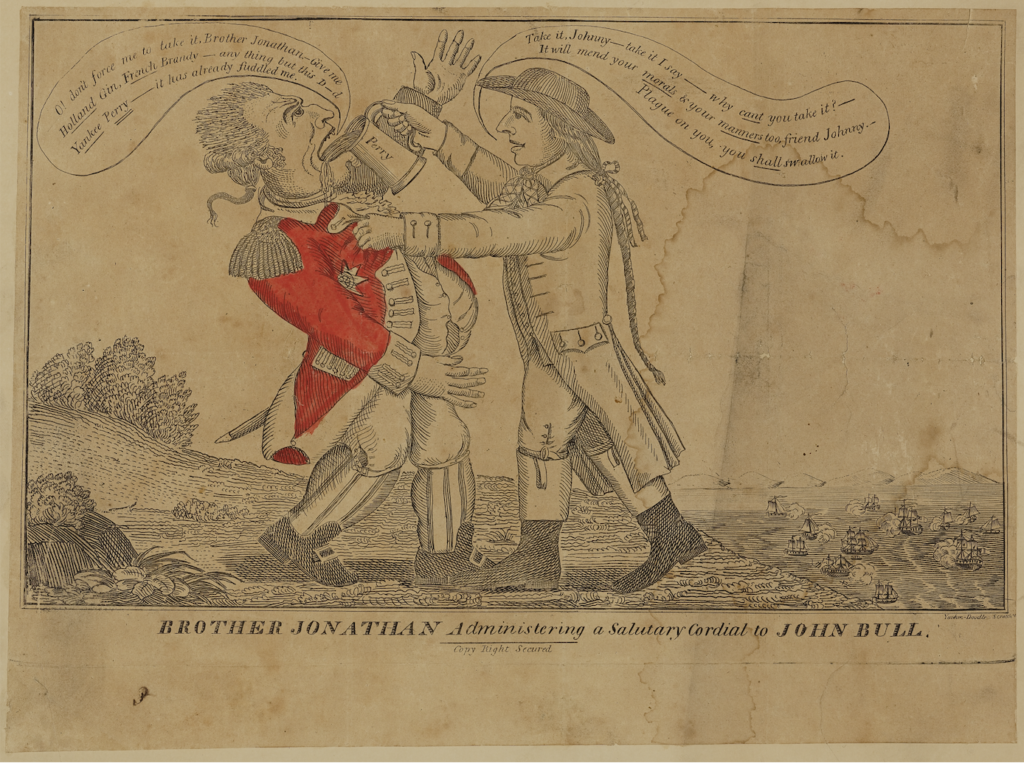

The Main Exhibition Building—reportedly the largest building in the world at the time—enclosed twenty-one acres under one roof. The architectural marvel was 464 feet wide by a central nave 1,876 feet long and seventy feet tall, with displays on mining, metallurgy, manufacturing, and science. A contemporary cartoon celebrating the Centennial featured the mighty “Brother Jonathan,” a precursor of Uncle Sam, straddling the towers of the building. Between his feet, the North American continent, crossed by a railroad, appears on a half globe, above which hot-air balloons labeled “1776” and “1876” rise in the sky.

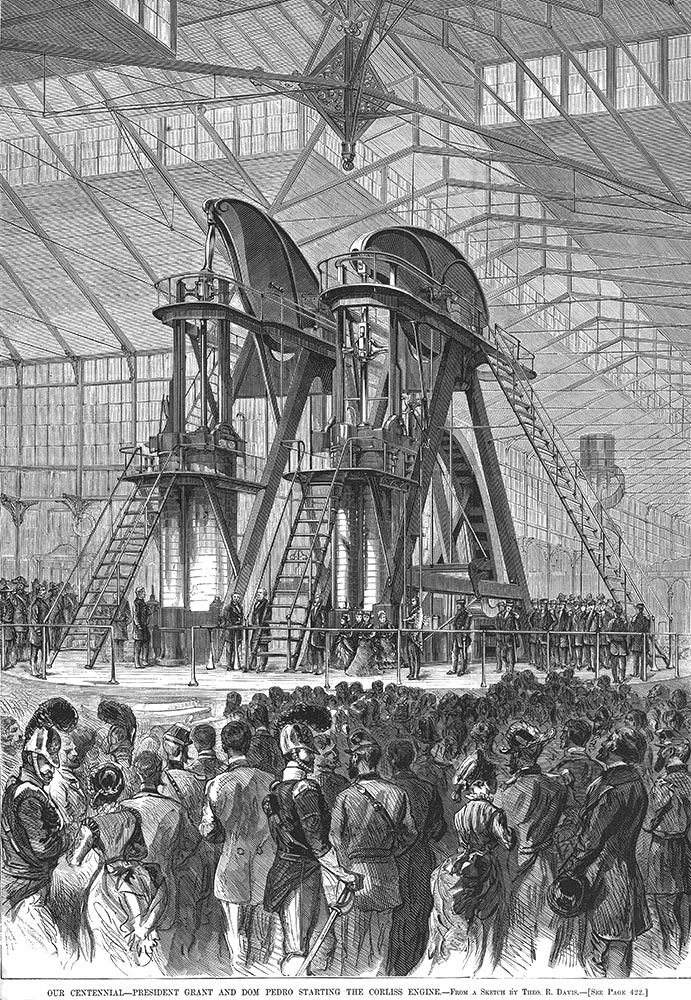

The buildings at the fair ranged in style from beaux arts to a Japanese temple, Moorish tents to Chinese pagodas. Fifteen countries (including England, Portugal, Sweden, Brazil, Japan, Egypt, Turkey, Chile, and Australia) built their own pavilions, as did twenty-six of the-then thirty-seven American states. The Machinery Hall, the second-largest building, elicited the most awe. Here, on the opening day, May 10, 1876, before a crowd of 110,000, President Ulysees S. Grant and Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil gave welcome speeches and then pulled a lever to start the George S. Corliss Steam Engine, a fourteen-hundred-horsepower behemoth made in Rhode Island that produced power for the entire building.

Other inventions prompting excitement included Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, Thomas Edison’s telegraph, the E. Remington and Sons’s first commercial typewriter, and —most popular—popcorn. There were new technologies, new foods, and new products everywhere. An immense display featured firearms made by firms like Colt, who had produced their first fearsome, rapid-fire Gatling gun. There were American-manufactured machines for combing wool and spinning cotton, printing newspapers and sewing leather, sawing logs and pumping water. The exposition was wildly popular, attracting nearly ten million visitors over six months at a time when the population of the states was estimated to be about forty-three million people.

It’s for these mechanical wonders that the Centennial is primarily remembered, but as its name implies, the fair also inspired Americans to look to their own past. Gore Vidal perhaps put it best in his acclaimed novel, 1876: “All summer long the country has been entirely preoccupied with the Centennial Exhibition, with sewing machines, Japanese vases, popped corn, typewriters and telephones, not to mention incessant praise for those paladins who created this perfect nation, this envied Eden, exactly one century ago.”

Central to this political message were colonial-era relics honoring the nation’s founders, among them George Washington’s uniform and his Revolutionary War tent from 1777—an oval, flax-linen tent twenty-three feet long and fourteen feet wide with a scalloped red wool border. It served as Washington’s war headquarters and was often referred to as “the first oval office.” For one hundred years it has been carefully preserved by a devoted nation.

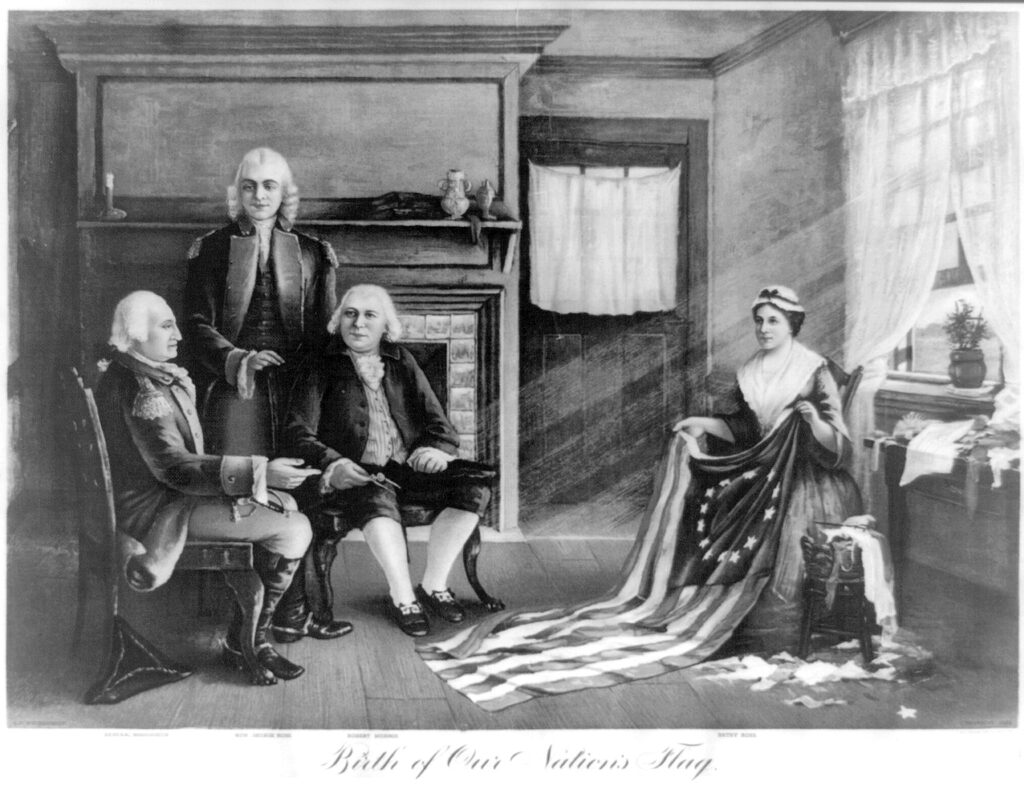

A rare example of a founding mother, Betsy Ross, only came to fame at the Centennial. It was at this time that she became legendary as the seamstress of the first American flag bearing the stars and stripes, purportedly designed in 1776 with input from Washington himself. This story was first presented by her grandson, William J. Canby, in a speech to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1870. Canby was only eleven when Ross died, but he was raised with tales of his grandmother’s skills, pluck, and loyalty to Washington and the Revolutionary cause, and he was determined to spread her legacy.

But did she really sew the first stars and stripes? “There is no doubt that Ross was working as a Philadelphia flag maker in 1777,” Marla R. Miller writes in her book, Betsy Ross and the Making of America, “and over her 60-year career she made hundreds of flags—archival references can be found for dozens she fabricated for state and federal forces. But it is impossible to know today who the makers of almost any battle standards were, in part because such artifacts are unsigned, and also because records documenting flag construction are so rare.”(1) Despite scholarly skepticism about Canby’s story, it was immediately embraced at the fair. The legend of the heroine maker of our Stars and Stripes has only continued to grow since: today her house in Philadelphia, now a museum, is one of the most visited tourist sites in the city.

Emblems of patriotism were everywhere at the fair, including a stand that featured colonial-era “Liberty flags,” which had originated in the 1760s as symbols of anti-British protest. These included the Pine Tree flag of the Massachusetts colonial navy, the 1775 rattlesnake flag of South Carolina (a yellow field dominated by a coiled snake above the words “DON’T TREAD ON ME” designed by Christopher Gadsden), and several thirteen-star flags representing the original colonies. “A fascination with the flag emerged over the course of the 19th century and blossomed in the wake of the Civil War,” Miller writes. “A symbol of union drenched in the sacrifice of hundreds and thousands of men, the United States flag, in the decade of the nation’s centennial, came to signal the ‘patriotic ideal.’”

Beyond such specific allusions to the Revolution, the fair also encouraged nostalgia for the colonial era, portrayed as a simpler time. One popular destination for visitors was the New England Log Cabin, whose quaint architecture offered a romanticized image of colonial life. It displayed a cradle said to have been used by Peregrine White—the first child born to the Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower in 1620—as well as a sword worn by Captain Nathan Barrett during the Battle of Concord in April 1775, a silver teapot linked to the Marquis de Lafayette, and a two-hundred-year-old chair that belonged to Massachusetts’s colonial governor John Endecott. A woman in colonial dress working a spinning wheel helped create the atmosphere of “olden times.” Other colonial era artifacts in the Carriage Building included early American furniture, household utensils, wood stoves, willow work, wooden plates, copper kettles, and pewter platters.

Intentionally or not, this cult of bygone simplicity found a correspondence in glorifications of the American West, represented at the fair by ravishing paintings by Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt, and, near the Centennial Lake, by a wooden salt-box Hunter’s Cabin. Representing the abode of a western hunter or trapper, it contained all the paraphernalia needed by an “ingenious pioneer.” According to an account in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition of 1876: “Inside, standing against the walls, or hung on pegs, are fishing tackle, a panther’s head, the horns of Rocky Mountain rams, hides of huge black bears, buckskin coats, leggings and moccasins captured from Indians, a snow-white hide of a polecat . . . stuffed prairie chickens and ducks and a score of other curious trophies.”

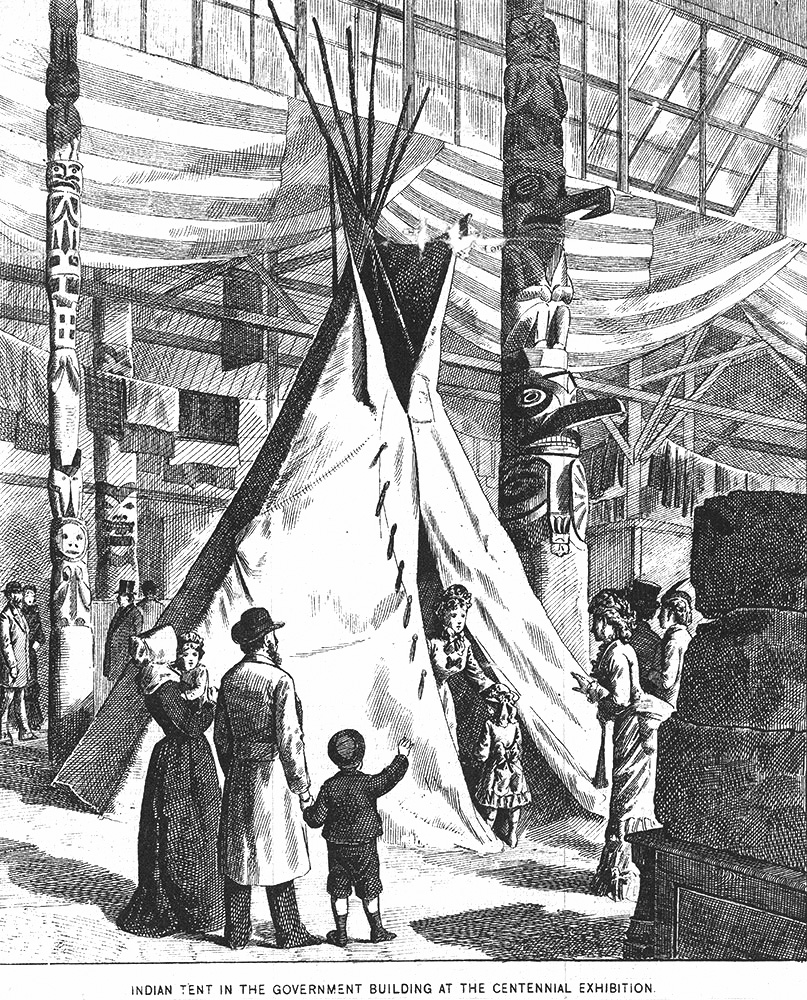

Another aspect of nostalgia at the fair extended to Native Americans, who were presented as exotic beings. In the Photography Building, a show of 126 oil paintings by the late George Catlin titled “Illustrations of Indian Life” depicted Native American tribesmen as they lived, hunted, and raised their families. The Tiffany & Company stand featured metalware sculptures of proud Native American chiefs. In the United States Government building a trove of artifacts on display included masks, pipes and tobacco pouches, pottery, bead and wampum work, clothing, charms, ornaments, tools and weapons—including a Hopi throwing stick, a wooden Haida ax, and a Sioux bow made of the sliced horns of mountain sheep. A towering totem pole from the Northwest was decorated with carvings of humans, frogs, beavers, and bears. There was also a genuine wigwam, sixteen feet in diameter, made of smoked buffalo skins, and a group of life-size mannequins (that looked suspiciously like cigar store Indians) wearing “Indian dress.”

On June 25, 1876, little more than a month after the Centennial opened in Philadelphia, the Civil War hero General George Custer and his troops were massacred at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The news had a huge impact. Custer was immediately deified as a martyr killed by “red savages.” Public outrage gave support to the US government’s brutal efforts to force Native American tribes into subjugation and onto reservations. Oddly, his fate also led to the elevation of the myth of the everyday plainsman of the West. A former scout for General Custer, William F. Cody, aka Buffalo Bill, soldiered in the Civil War, hunted buffalo, and rode for the Pony Express. He was described as daring, resourceful and “tough as rawhide.”

Eventually he became a showman after a dime novelist, Edward Z. C. Judson (pen name: Ned Buntline), wrote a play, Scouts of the Prairie, that starred Cody himself in 1872. In time, five hundred Buffalo Bill dime novels were published. In 1883 Cody founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a highly successful traveling show that re-created scenes from the American West, with rough riders like Cody himself and celebrities like Annie Oakley. The show toured the United States and Europe for thirty years and played a role in romanticizing the American frontier for both European and American audiences.

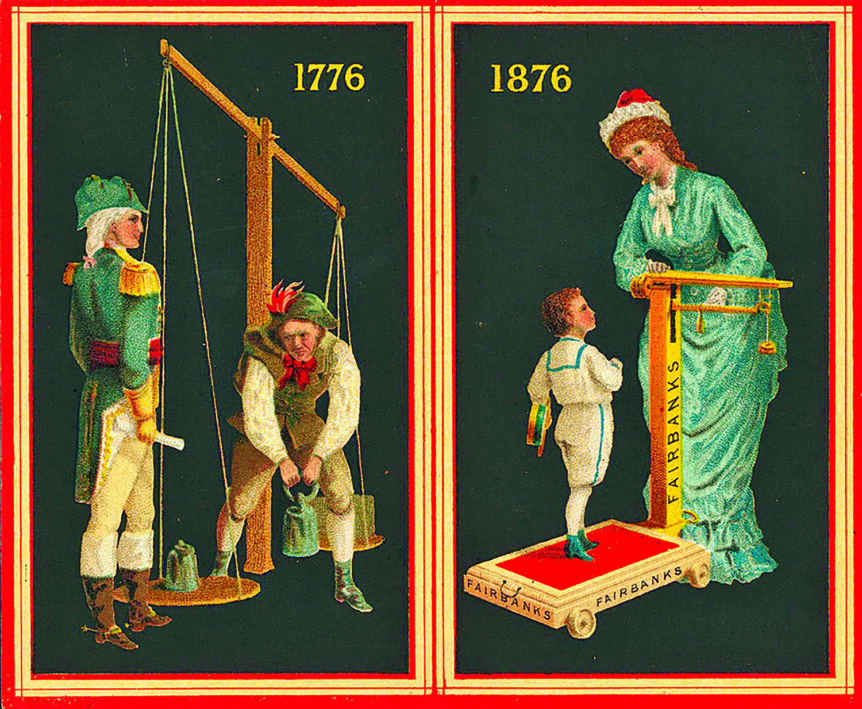

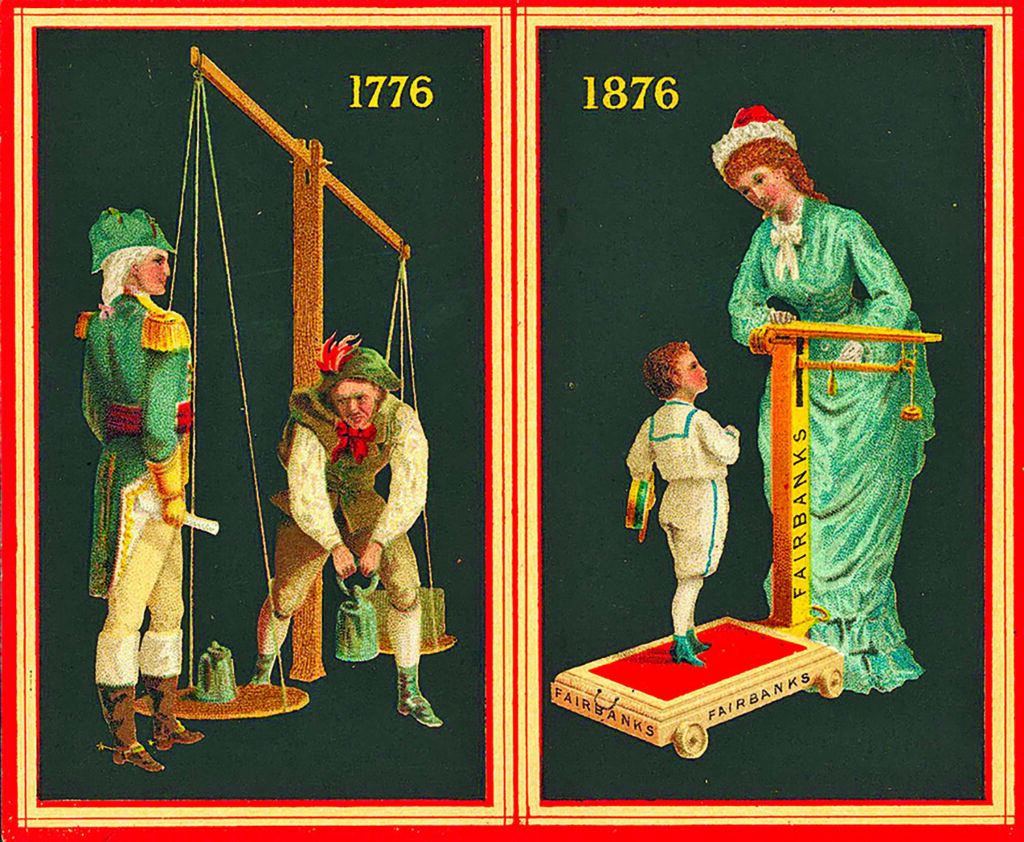

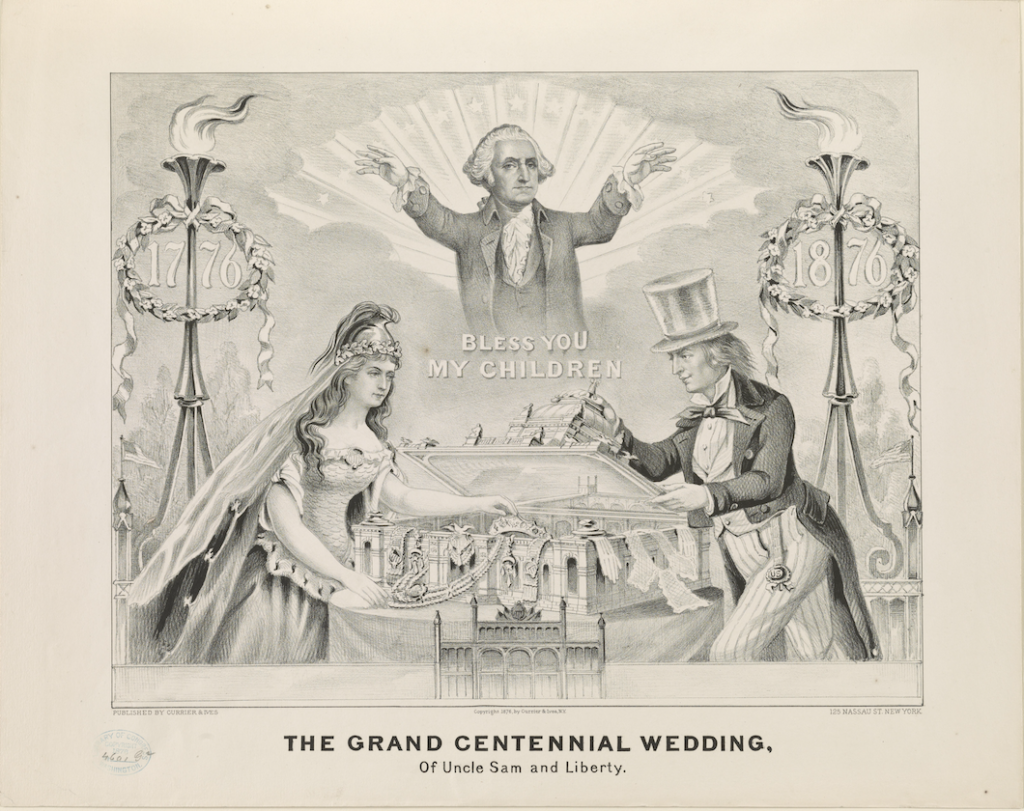

“Though the Centennial was designed to celebrate the theme of progress, the historical exhibits ultimately had the effect of raising interest in and appreciation for America’s colonial past,” the Leslie Register concluded, noting “Americans’ increasing enthusiasm about collecting and preserving colonial furniture, ceramics, textiles and decorative arts.” In fact, it has been argued that the fair launched the colonial revival movement. The Grand Centennial Wedding, a popular Currier and Ives print of that year, symbolizes the moment, with a depiction of George Washington blessing the nuptials of Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty. At a time of upheaval and rapid change—rampant corruption in President Grant’s cabinet, strikes by union workers, boatloads of new immigrants sparking xenophobia, the end of Reconstruction, the financial panic that began in 1873, and a stolen presidential election in 1876—the citizenry welcomed the centennial celebration as a reverie of early America.

Or at least, some of them did. “The influx of foreign ideas utterly at variance with those held by men who gave us the Republic, threaten, and unless checked, may shake the foundations” of the country, wrote R. T. H. Halsey, a wealthy collector of Americana and a leader of the emergent colonial revival movement. Men like Halsey preferred the time when heroic pioneers sustained their families through honest labor, and patriotic farmers fought for freedom beside selfless founding fathers. Their view may have been romanticized, but it was widely shared.

To Americans descended from earlier stock, in particular, the “real” America was often perceived as under siege. Soon after the Centennial, they formed exclusive societies, including the SAR (Sons of the American Revolution), the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution), and the Colonial Dames of America. Such organizations “gave members a connection to the nation’s origins that drew clear distinctions between them and their fellow Americans,” American historian Michael D. Hattem writes in The Memory of ’76: The Revolution in American History; some of those “fellow Americans” were new immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Italy, Greece, Russia, and Hungary.(2)

After the Centennial, Americans embraced colonial styles in architecture and decorating, abandoning fusty Victorian parlors filled with dark, carved furniture, dense ferns, bric-a-brac, and heavy damask for simple decor with plain furniture. The colonial revival only grew stronger as time passed. Companies sold popular reproductions of colonial ceramics, silver, textiles, and furniture (which, oddly, included Federal, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton styles from the early 1800s as well as true colonial styles like Willam and Mary and Chippendale). Eventually, the Metropolitan Museum of Art would open the American Wing, and new historic house museums appeared across the country in places like Williamsburg in Virginia and Old Deerfield in Massachusetts. One might argue that the colonial revival has never really ended, and that nostalgia for the American past has become a tradition in its own right. And this is no bad thing: as Adam Gopnik has recently written in The New Yorker, “Reverence for the past, and reluctance to destroy until the risks of destruction are fully known, is not timidity but wisdom, in architecture as in life.”(3) Just as much as the machinery of progress, this is the legacy of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876.

WENDY MOONAN writes about art, architecture, and design and is the author of the Rizzoli best seller New York Splendor: The City’s Most Memorable Rooms.

Endnotes:

(1) Marla R. Miller, Betsy Ross and the Making of America (New York: Henry Holt, 2010)

(2) Michael Hattem, The Memory of ’76 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), p.123

(3) Adam Gopnik, “Teardown,” New Yorker, November. 3, 2025, p. 9