The official national celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence nearly didn’t happen. Despite a decade of advocacy from business and political leaders in Philadelphia—who saw the city as the natural home for a world’s fair to commemorate the country’s Sesquicentennial, as both a key birthplace of the American republic and the prior host of the Centennial Exhibition in 1876—the planning and execution of the Sesquicentennial International Exposition was a turbulent process of false starts, delayed decisions, and conflict within the city’s political and philanthropic communities. Federal support was slow to materialize; Congress did not approve funds for the Sesquicentennial until February of 1925, and uncertainty about cash flow required scaling back the fair’s scope multiple times.(1) Even when it was opened on May 31, 1926 (supposedly “ahead of schedule,” though large portions of the grounds and exhibits were still incomplete), long stretches of bad weather resulted in uneven attendance. The exposition ultimately saw just a fraction of its projected forty to fifty million visitors.

In its rocky path to realization, the Sesquicentennial mirrored the many contradictions of the 1920s United States. A humming economy and flourishing urban artistic communities sat uneasily alongside entrenched political machines, racial segregation, and rural poverty. The reach of film and radio connected more people than ever before, while strident anti-immigrant discourses divided them. The “Machine Age” seemed to offer a future of prosperity and convenience, even as industrial workers saw their working conditions deteriorate and their labor rights erode. Hints of these contradictions come through in a poster for the exposition, showing an allegorical America—complete with Phrygian cap denoting liberty and equality—standing above the engineering marvel of the Delaware River Bridge (today the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, completed in 1926 and dedicated as part of the Sesquicentennial celebration). The fictive classicizing cityscape is caught between historicism and modernity. The poster announces “America Welcomes the World”—but it was a provisional welcome only, as the immigration restrictions of the 1921 Emergency Quota Act and 1924 Asian Exclusion Act had made clear.

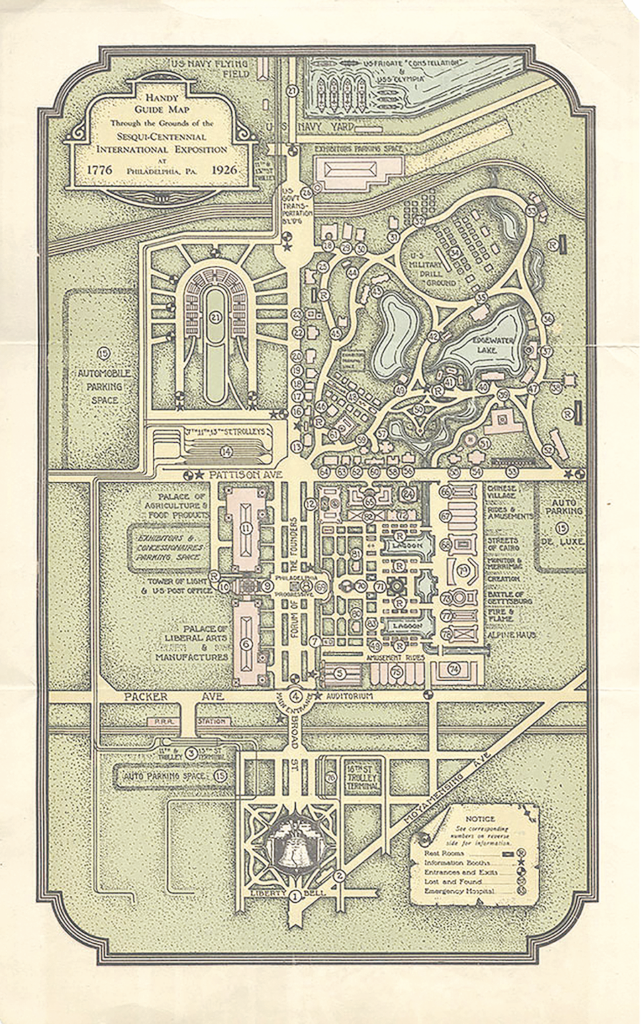

The Sesquicentennial was built atop a swampy, largely undeveloped plot of land, adjacent to the Navy Yard in South Philadelphia. The original plan had been to build in Fairmount Park, site of the 1876 Centennial; the relocation came late in the planning process, in what many saw as a blatant favor from Philadelphia mayor Freeland Kendrick to William S. Vare, a Pennsylvania Congressman with real-estate interests in the area and deep ties to Philadelphia’s political machine.(2) Even so, the fairground was modeled broadly on world’s fairs past. Large exhibit halls devoted to manufacturing and technology lined a central “Forum of the Founders,” surrounded by smaller buildings acting as hospitality spaces, specialized exhibits, and performance venues. Waterways and formal gardens graced the wide interstitial spaces. There were fewer official buildings sponsored by foreign nations than might be expected for an international exhibition, due to the rushed planning process and the US government’s lukewarm support, but twenty-three countries did have a presence—some without their government’s formal involvement, and some integrated in exhibit halls rather than freestanding pavilions.(3)

Two particular features of the Sesquicentennial plan established it firmly as a product of the Roaring Twenties. First were the midway-style entertainments and vendors, typically sited at a decorous remove in earlier expositions, but here integrated more fully into the design. This frank commercialism—and the traffic jams that clogged major events at the exposition grounds—earned the fair the (unflattering) nickname “Kendrick’s Karnival.”(4) And all those automobiles were a second sign of the times: a technology then reshaping American cities and identity alike. Broad streets accommodated the fleets of limousines of important visitors and large swaths of ground were devoted to parking, presaging the expanse of asphalt that now covers much of the site as Philadelphia’s present-day stadium district. With four hundred acres to accommodate around a hundred thousand vehicles, the Sesquicentennial’s parking space was nearly as large as the fairgrounds proper.(5) While streetcar lines and a temporary station of the Pennsylvania Railroad did serve the fairgrounds, the overall plan pointed to the increasingly central place of the car in American life.

Entering the fairgrounds, visitors passed beneath a monumental effigy of the Liberty Bell that spanned Broad Street like a ceremonial arch. They might have had trouble seeing the slogan “Spirit of 1776” amid the glare of the twenty thousand light bulbs that covered the bell’s surface. This exaggerated monument was just one of many collisions between the exposition’s ostensible commemorative aims and the temptation to stage a spectacle of modernity. Gargantuan exhibit halls continued the theatricality, designed in what City Architect John Molitor called a novel “exhibition style” that “evolved for the occasion.”(6) Echoing the lexicon of art deco—geometric motifs and abstracted classical forms—taking shape in many American downtowns, Molitor concentrated architectural detail at the corners and entrances of the buildings. The rest of their massive volumes were rendered in plain colored plaster over hangar-like steel skeletons. While the architect and fair boosters characterized this approach as a bold new direction for American architecture, it was also, crucially, cheap and quick to build, allowing for construction in roughly six months.(7)

Molitor’s rendering for the Palace of Liberal Arts and Manufactures also demonstrates the importance of electric power at the fair. In addition to the bulb-spangled Liberty Bell, dramatic colored lighting washed the colossal main buildings at night. Numerous exhibits attested to the mounting importance of electricity in Americans’ daily lives as well, with radios, washing machines, refrigerators, and other devices populating manufacturers’ displays. While few of the exhibits had the sheer impact of technological novelties at prior world’s fairs—the Corliss engine at the Centennial, or the Palace of Electricity at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, for example—they were a telling index of a major technological shift in the domains of mass production and consumption. (8)

Alongside these celebrations of commerce and industry, displays of historic American goods and production techniques summoned a longer narrative of American innovation, stretching back 150 years. While Molitor had rejected colonial references for the fair’s main buildings, noting that “any style depending upon the delicacy of its ornament and the refinement of its detail would be inadequate” for such huge edifices, the Sesquicentennial was nonetheless awash in allusions to the Revolutionary era.(9) As numerous scholars have noted, a nostalgic reengagement with America’s founding mythos offered a means of compensating for modernization’s disruptive effects, and projected a unified sense of national identity in an increasingly pluralistic society. As Kenneth L. Ames has written, partisans of the colonial revival looked to preindustrial buildings and objects through “appealing assumptions about old-time craftsmanship, the piety and patriotism of the original owners, and the moral superiority of an earlier age.”(10)

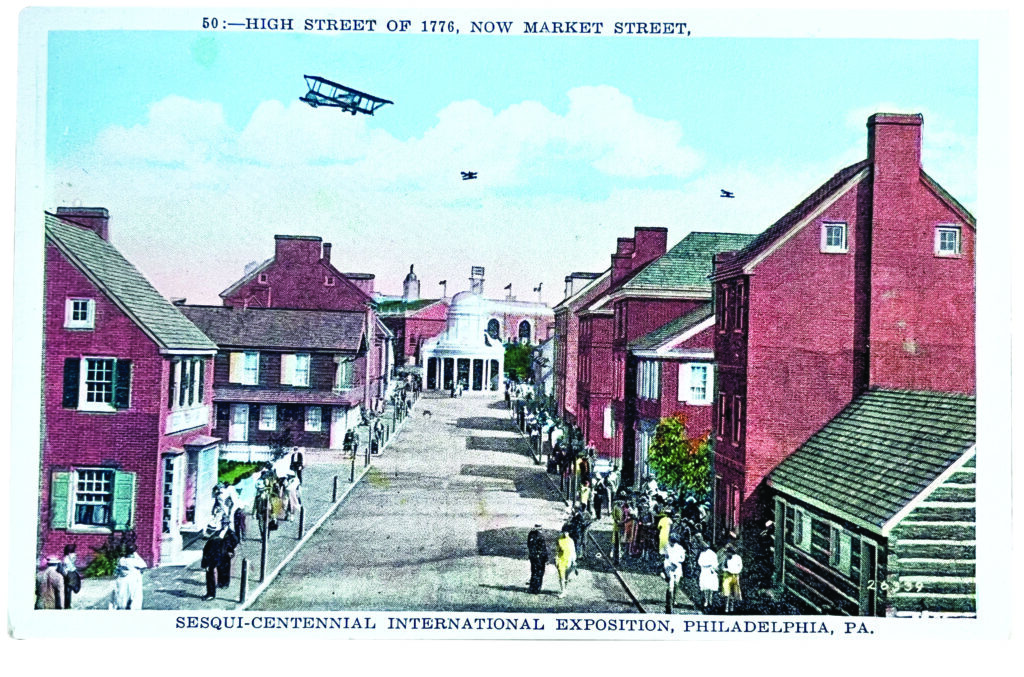

The most potent example of this phenomenon at the Sesquicentennial was the High Street of 1776. Mounted by a coalition of women’s organizations, the full-scale evocation of Philadelphia’s colonial-era main commercial street (today the city’s central Market Street) was one of the most successful elements of the fair. Replicas of no-longer-extant buildings were arranged in an atmospherically suggestive rather than historically faithful ensemble—a convincing simulacra, despite inexpensive, ersatz materials and construction techniques. Workers in period costume heightened the illusion. Visitors could watch demonstrations of blacksmithing and printing techniques or visit a market under the re-created Town Hall for handicrafts and souvenirs. As architectural historian Lydia Mattice Brandt has argued, the High Street represented an explicit call for renewed patriotism, and implicitly, for the assimilation of immigrant communities.(11) In the words of one of its chief planners, the prominent suffragette Sarah Dickinson Lowrie, “we do not have to stand still in order to be loyal to a great past, but in certain essentials we have to carry out the ideals of that past or we shall lose our heritage.”(12)

Within the larger colonial revival, the home was a key locus of individual morality, familial and societal cohesion, and even national memory. The organizers of the High Street made this explicit, with a subtle note of censure aimed at the sorts of manufactured novelties on ample display elsewhere at the Sesquicentennial: “all the essentials of a home existed [in 1776] and on the High Street of Washington’s, Franklin’s, and Jefferson’s day,” one fair publication asserted. “We cannot improve upon those essentials, we can only amplify them and honor the original valuations of them, by making the most of the ideals that we owe to the first makers of homes in this country.”(13)

This claim was put into practice on the High Street. Several of its replica buildings had furnished interiors that landed somewhere between the idioms of the historic house and the model home; these were sponsored by department stores, decorating firms, and even Good Housekeeping magazine, and populated largely with contemporary reproductions of colonial antiques. In the case of the Washington House, a re-creation of the first president’s Philadelphia residence sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution, the local Arts and Crafts Guild coordinated the production of handmade reproduction furniture and other decor with an express goal of “encouraging the work of living craftsmen.”(14) Even as assembly lines were extending across factories, the colonial revival served as a vehicle for craft survival, just as much as an escapist gesture toward the past. The High Street also helped to revive interest in colonial-era historic houses still standing in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, prompting conservation efforts in subsequent years; it might have also been on the minds of the philanthropists and preservationists who commenced restoration efforts at Colonial Williamsburg in late 1927. (15)

In practice, of course, few fair visitors would have wanted to cook on an open hearth. Some voices at the fair acknowledged the impartial appeal of nostalgia, arguing that modern comforts could (and indeed should) coexist with the preservation of national memory. In Good Housekeeping’s re-creation of Dr. William Shippen Jr.’s house, up-to-date kitchen, bathroom, and laundry facilities proved that “one can possess one’s ancestral home and be modernly at home in it.”(16) Saturday Evening Post columnist Elizabeth Frazer cast the Sesquicentennial Exposition as a reckoning between America’s founding principles and its contemporary moral ambiguities: “This constant juxtaposition of the present beside the past, which is the dominating note of the exposition, is . . . somewhat like an adult man looking down upon the dim, faded photograph of the boy he used to be. Is he still the same passionate idealist that clear-eyed lad was? Has he kept faith with himself, with his clean, high intentions? Or have life and the struggle for material prosperity blunted his fine edge and transformed him into a thick-hided selfish egotist, content in his own drab little windowless cell of clay?” Perhaps thinking of the contrast between the patriotic High Street and its commercialized, politically compromised surroundings, Frazer continued: “1776, its very spirit and mood, seems to emerge out of the mists of time like a great impalpable ghost and to hover broodingly, austerely questioning, over 1926.”(17)

While the Sesquicentennial quickly faded from public memory after its closure—perhaps owing to the lingering embarrassment of its messy planning and poor attendance—at least one visitor kept brooding over 1776. George Persak, a Yugoslavia-born immigrant blacksmith who worked in the automobile and appliance industries, was so struck by his experience of the exposition that he made a massive homage to his adopted country. Standing ten feet tall, The Symbol of ’76 (as he called it) took him over two decades to build. The sculpture is composed of thousands of individual elements of hand-chased and lacquered copper bearing portraits of statesmen and military figures who shaped the early republic, renderings of important buildings and sites of Revolutionary history, and the entire texts of the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. Apparently a solitary man, Persak worked entirely at home; the sculpture was only found upon his death, disassembled, and carefully wrapped.(18) Persak’s earnest love for the American story makes The Symbol of ’76—at once ambitious and deeply personal, made in a period of stark anti-immigrant politics—a poignant mirror to the ambiguous commemorations of 1926.

COLIN FANNING is a design historian and Assistant Curator of European Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Art Museum.

Endnotes:

- See “Sesquicentennial Exhibition, Philadelphia: Hearings before the Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions, House of Representatives, Sixty-Ninth Congress, First Session, on H.J. Res. 144, February 3 and 4, 1925” (Government Printing Office, 1926). For a fuller narration of the convoluted planning process, see Thomas H. Keels, Sesqui!: Greed, Graft, and the Forgotten World’s Fair of 1926 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017).

- “Philadelphia Fair Appears Assured,” New York Times, December 9, 1925; see also Keels, Sesqui!, pp. 51–53. 68.

- “Hearings before the Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions,” pp. 61–62.

- E. L. Austin and Odell Hauser, The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition (Philadelphia: Current Publications, 1929), pp. 48–49; see also Keels, Sesqui!, pp. 124–125.

- “Hearings before the Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions,” pp. 49, 51.

- John Molitor, “How the Sesqui-Centennial Was Designed,” American Architect, vol. 130, no. 2508 (November 5, 1926), p. 380.

- W. Freeland Kendrick, “Foreword,” in Austin and Hauser, Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition, p. 10.

- See Lawrence B. Glickman, “Rethinking Politics: Consumers and the Public Good During the Jazz Age,” OAH Magazine of History, vol. 21, no. 3 (July 2007), pp. 16–20.

- Molitor, “How the Sesqui-Centennial Was Designed,” p. 380.

- Kenneth L. Ames, “Introduction,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod (New York: Norton in association with the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1985), p. 7.

- Lydia Mattice Brandt, “Picturing Female Patriotism in Three Dimensions: High Street at the 1926 Sesquicentennial,” in Meet Me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader, ed. Laura Hollengreen, et al. (Pittsburgh; Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2014), pp. 127–142.

- Sarah D. Lowrie, “Foreword,” in Sarah D. Lowrie and Mabel Stewart Ludlum, The Book of the Street: The Sesqui-Centennial High Street (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1926), p. 12.

- Ibid., pp. 10–11.

- “The Washington House at the Sesqui,” American Magazine of Art, vol 17, no. 11 (November 1926), p. 596; see also Sarah D. Lowrie, “The Street of 1926,” in Lowrie and Ludlum, The Book of the Street , pp. 72–73; and Brandt, “Picturing Female Patriotism,” pp. 136–137.

- Austin and Hauser, The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition, p. 23.; see also, e.g., “Rockefeller Gift for Historic Town; Banker Pledges Fund, Which May Reach $5,000,000, to Restore Williamsburg, Va.,” New York Times, June 13, 1928.

- Lowrie, “The Street of 1926,” p. 76.

- Elizabeth Frazer, “1776–1926 at the Sesqui-Centennial,” Saturday Evening Post, vol. 199, no. 1 (September 11, 1926), p. 50.

- John Corr, “A Croatian Blacksmith’s Testimonial to America,” Today [magazine of the Philadelphia Inquirer], October 24, 1971, pp. 13–15, 18, 21.