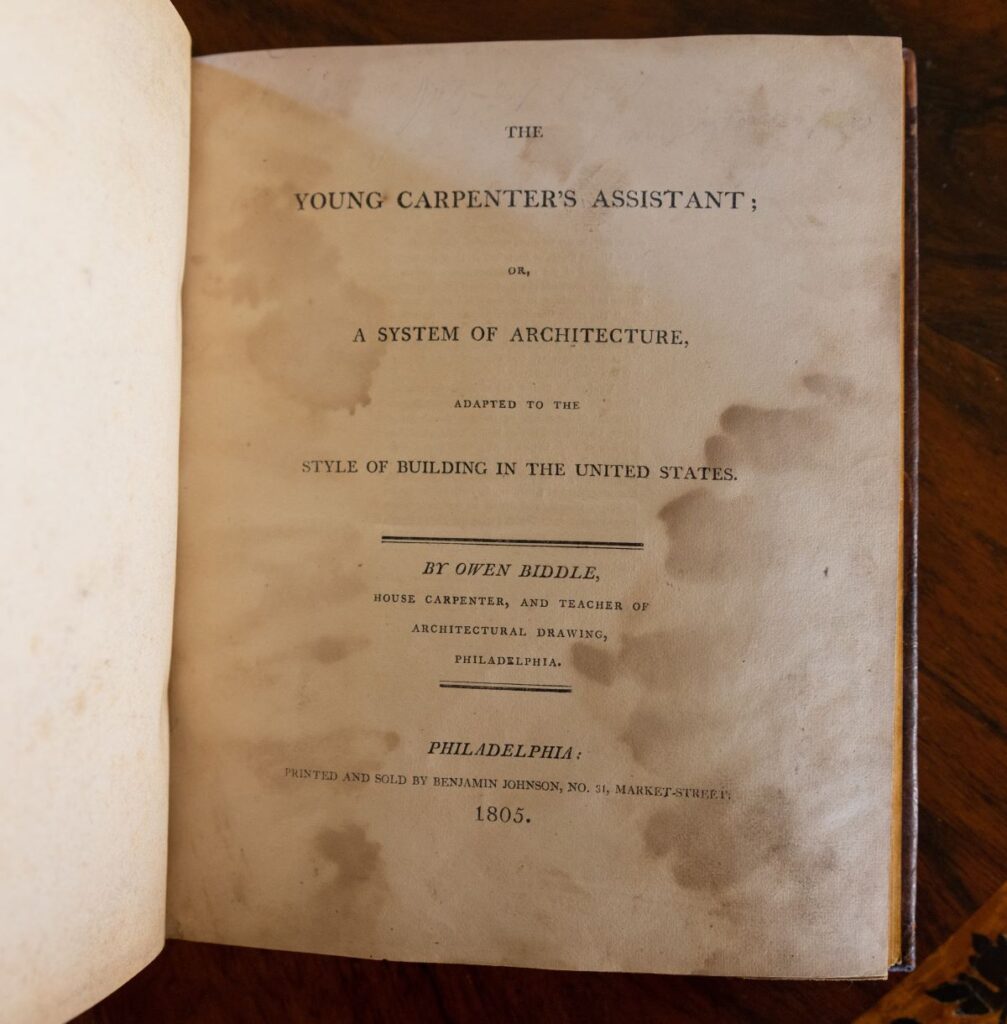

As the ink dried on the Treaty of Paris and gun barrels cooled across the newly minted states, the leaders of the new American Republic began the arduous work of creating the fabric of a new society. As part of that program, a need was felt for a new architecture, weaned from the fawning fashion for European styles, and celebrating the vigor of a New Age—a new classicism for a new republic. “I have experienced much inconvenience, for want of suitable books on the subject,” Owen Biddle Jr. wrote in 1805 in the preface to the first edition of his book The Young Carpenter’s Assistant; or, A System of Architecture, adapted to the Style of Building in the United States. “All that have yet appeared, have been written by foreign authors, who have adapted their examples and observations almost entirely to the style of building in their respective countries, which in many instances differs very materially from ours.” It was time, Biddle believed, for the codification of an architecture made just for America.

While Biddle was technically incorrect in his assertion that all books on architecture available in the United States at that time had been written by foreign authors—Connecticut-born Asher Benjamin (1773–1845) wrote the first book of American architecture, The Country Builder’s Assistant, in 1797—he was not wrong insofar as he conveyed the sense of isolation felt by American carpenter-builders and housewrights of the era. They felt themselves to be playing second fiddle to the builders of Europe, having to make do with whatever they could find among the scraps of the European cultural banquet. Men like Biddle were determined to see this change.

When Europeans first built permanent settlements in North America, they brought with them the construction methods and styles they knew from their homelands. The early colonial era of American architecture—especially the architecture of New England, New York, and Pennsylvania—is defined by adaptations of Tudor and late medieval styles. These styles were slowly replaced with elements of the Georgian style, reflecting the influence of British tastes and training. Even as towns and cities in the colonies became more sophisticated and craftsmen grew more specialized and skilled, the built environment continued to look like the European models then in vogue.

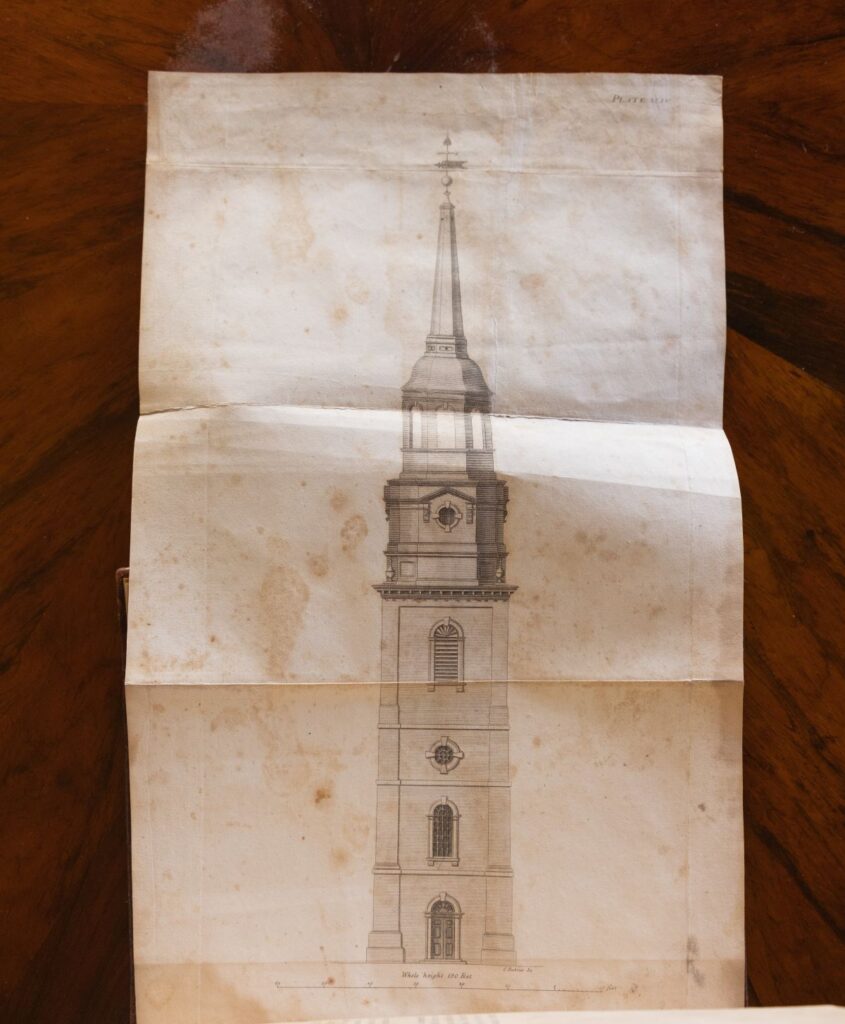

This process of aping and adaptation is a far cry from the rough-hewn construction by unskilled but eager workers that many imagine characterized most structures built in the young nation. These early buildings were, rather, the product of well-understood general methods and designs being adapted to a given clime and the resources available. Which adaptations were needed was learned through experience, but familiarity with techniques and design elements was acquired either through an apprenticeship with an experienced builder or by reading guidebooks. Most often, a young builder learned from both. This was true for many trades at the time, as attested to by the prevalence of furniture made to the specifications of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director of 1754. In the late eighteenth century, anyone who made furniture knew Chippendale’s Director, and many learned how to build a chair with one eye regularly glancing at its pages for guidance.

Biddle’s Young Carpenter’s Assistant was one of these vade mecums. The book was manual, glossary, and guidebook. It presented design vocabulary, history, and practice from Biddle’s perspective—that of a builder who was translating what he considered to be the best of English architecture into a package especially fit for the early American landscape.

A carpenter-builder, as Biddle called himself, was an architect, general contractor, and construction worker all in one. The son of a clockmaker, one of ten children, and a member of the fifth-generation of Biddles born on North American soil, he found a passion for shaping the built landscape of his native Philadelphia. After apprenticing under Joseph Cowgill from 1799 to 1801, Biddle struck out on his own at twenty-seven and became a member of the Carpenters’ Company guild. He was involved in the construction of the first covered bridge in the young country, the Schuylkill Permanent Bridge, and designed and built homes in Philadelphia’s Society Hill neighborhood that still stand today.

A committed Quaker from a line of committed Quakers dating back to William and Sarah Biddle, who arrived from England in 1681, Owen Biddle Jr. also designed and built the Arch Street Meeting House between 1803 and 1804. Biddle wrote the Young Carpenter’s Assistant at the same time as the building of the meeting house, which is in a symmetrical, neoclassical style and connects strongly to the vision put forward in the book. The two, the book and the building, are, in a way, a pair. The building is the incarnation of both the dream and direction the book puts forth.

Biddle passed away before his dream could be completely realized. He built the center hall and East Room in 1804, but the West Room wasn’t completed until 1811, five years after his death in 1806 at the age of thirty-two. He was laid to rest in the meeting house cemetery, which would be closed to new burials in 1880. The graves of most of the estimated twenty thousand individuals interred there are unmarked, as is Quaker tradition. The meeting house, however, is still in use, and prospective visitors can book private tours or visit virtually online.

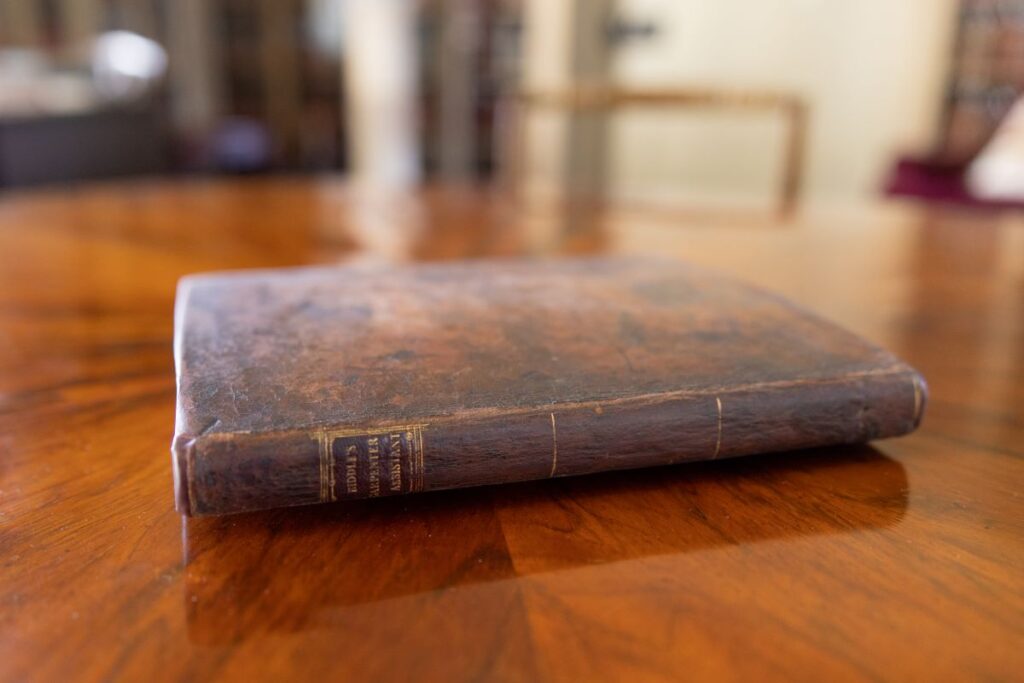

Biddle’s book has gained value among collectors because his death at a young age resulted in few published editions, and because many copies had their drawings removed for use as shop references, making complete early editions particularly valuable. According to Raptis Rare Books, only two copies of the book have appeared at auction in the last fifty years. One is now in the collection of Andalusia Historic House, Gardens, and Arboretum—which maintains the

Biddle family’s historic eighteenth-century estate just north of Philadelphia—while another sold at Sotheby’s in January 2023 for $3,000. Raptis currently has a finely re-bound first edition copy on offer for $15,000 in its gallery in Palm Beach, Florida. For Andalusia, holding Biddle’s book is part of the institution’s evolving effort to “widen the institutional definition of the Biddle family,” says John Vick, director of the estate and its collections, “beyond those who lived at Andalusia and their descendants to include descendants of all Biddles going back to William and Sarah.”

Matthew Raptis advises those considering books as collectable objects to let their own reading interests lead them into the pastime. Though he began his collection as a kid with Civil War books, he now cherishes his first edition of Don Quixote. As a book dealer, he sees his role as being more matchmaker than salesperson. Books are intensely personal, they require careful storage and handling to maintain value, and yet beg to be used. He says the provenance of his copy of Biddle’s book has yet to reveal itself, but the name “Rob Davidson”* inscribed inside provides a clue, along with a pencil drawing of a flower.

*Like Owen Biddle, Pippa Biddle is a descendant of William and Sarah Biddle. There is no known relation between Benjamin Davidson and the “Rob Davidson” of the inscription.