English inspiration, American creativity, and a bit of historical luck are joined in the author’s house and gardens

Several years ago English friends came for lunch at my house, now called the Gordon-Banks house, in Newnan, Georgia, some forty miles southwest of Atlanta. They walked down a wide hallway onto a porch that overlooks a terrace and what the English call “the park”—in this instance, a broad sweep of lawn trimmed with trees and shrubs that slopes to the banks of a small lake (see Figs. 1, 3). “Why!” one of the guests exclaimed, “You have a Capability Brown landscape.” I accepted the compliment, since Lancelot Brown (1716–1783), who was called Capability because he was quick to discern the capabilities of an estate, was the most eminent landscape gardener in England for much of the eighteenth century. However it is the work of his successor Humphry Repton that I believe has an affinity with the park and formal gardens at the Gordon-Banks house. My father, William N. Banks Sr. (1884–1965), had acquired the property in the late 1920s and worked with William C. Pauley (1893–1985), a landscape architect, to create a pleasing landscape in the English style.

In the 1820s, a hundred years before my father built a Tudor-style house on the property in Newnan, John W. Gordon (1797–1868), an affluent cotton planter, hired a young carpenter named Daniel Pratt (1799– 1873) to build an impressive house on his plantation near Milledgeville, Georgia. Pratt was born on a farm in Temple, a village in southern New Hampshire, and at sixteen was apprenticed for five years to a master carpenter, Kimball Putnam. After four years, when Putnam suffered financial reverses, Pratt reckoned that his best prospects lay in the South where, thanks to Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin, the planters were prospering as never before. The enterprising youth borrowed twenty-five dollars from his grandfather and sailed from Boston to Savannah in November 1819 with no possessions except his carpenter’s tools and, most likely, a copy of Asher Benjamin’s book The American Builder’s Companion. He worked there for a year or so before moving to Milledgeville, the capital of Georgia from 1805 to 1868. Although there is little documentation, it seems that from 1821 to 1831 Pratt built at least eight remarkably elegant neoclassical houses in the town and on nearby plantations.

The façade of the house he built for John Gordon features a portico with a pediment and balcony supported by two slender Roman Doric columns; Doric pilasters ornament the corners (Fig. 1). Inside, an arch trimmed with gilded acanthus leaves divides the central hall, and at one end a circular stair ascends two flights to the attic (see Fig. 4).

Although Pratt would have described himself as a carpenter or builder, not an architect, he did in fact design the houses he built. However, for a number of the decorative elements he relied on drawings in Benjamin’s American Builder’s Companion, first published in 1806. Pratt’s successful applications of Benjamin’s designs at the Gordon house include the configuration of the balusters on the porch and balcony; the cone-shaped guttae, instead of the ubiquitous dentils, that trim the external entablature; and the resplendent fanlight spanning a double door in the hall. It seems remarkable, when Milledgeville was still a frontier town with Indians ensconced between the town and Alabama, that artisans were available to execute the expert millwork, the wood graining and marbleizing, and the elegant plaster decorations.

In the early 1830s Pratt decided that manufacturing was more lucrative than the building trade, and he believed there was greater opportunity farther west. He, his family, and two servants set out in wagons for Alabama, taking with them material for fifty cotton gins. Acquiring property near Montgomery, he founded a town and named it Prattville. He built a cotton gin factory where he manufactured an improved model of Eli Whitney’s gin, and before the Civil War the New Hampshire farm boy became Alabama’s first industrial millionaire.

In 1848 John Gordon sold his house to Thomas O. Bowen for eight thousand dollars and moved to Wharton, Texas, where he owned a large property. The Bowen family occupied the house throughout the Civil War and in November 1864, in the course of Sherman’s march through Georgia, General Francis P. Blair Jr. (1821–1875), commander of the Seventeenth Army Corps, briefly made the Bowens’ house his headquarters. Blair wrote his father in Washington boasting of the appalling damage he and his troops were inflicting—but, for whatever reason, he left the Bowens’ house untouched.

In 1881 Bowen sold the house to his brother-in-law James H. Blount of Macon, Georgia, and for more than a century it was sporadically occupied. In the 1940s, when the house was threatened with demolition by a lumber company, a professor at the college in Milledgeville, L. C. Lindsley, who considered the house an architectural treasure, bought it to preserve it. Although he never lived there, he diligently maintained the grand old house. In 1959, having seen photographs taken for the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1930s, I contacted Lindsley, and he graciously gave me a tour of the property. I was awestruck by a unique house that had remained virtually unaltered for more than a century; and, I confess, I fell in love.

In 1968, after Professor Lindsley’s death, my wonderful mother, Evelyn Wright (Mrs. William N.) Banks, persuaded a Lindsley daughter to sell her the house, and she chose a multi-talented architect, Robert Raley from Wilmington, Delaware, to move it. Within a year and a half Raley, supervising capable contractors and veteran artisans, managed to transfer the Gordon house from a barren field near Milledgeville to verdant surroundings in Newnan. Indeed, the park and gardens originally created by William Pauley and my father might have been designed to accommodate and enhance the house.

Of course the house was empty, with no furnishings whatever. Since I believe that if a house makes a strong architectural statement, that statement should be respected and reflected in its decor, I tried to collect furniture and paintings appropriate to this remarkable early nineteenth-century house. In the sun-filled parlor, with its original wood graining and marbleizing and its intricate plasterwork, there are lyre-back chairs attributed to Duncan Phyfe and a caryatid card table originally attributed to Charles-Honoré Lannuier and, more recently, to Phyfe (Fig. 8). In the dining room is a Sheraton style Massachusetts sideboard of about 1820 equipped with a butler’s desk (Fig. 9). To its left hangs a still life by Severin Roesen (c. 1816–c. 1872). The painting above the bookcase in the study (Fig. 10), a view of Mount Washington in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, was painted by Albert Bierstadt. Another White Mountain scene, this one by Asher B. Durand, hangs above the fireplace.

After the house was moved to Newnan, two flanking wings were built on the east and west sides to replace outbuildings that had been long ago destroyed. One houses the kitchen, the other a gallery of nineteenth-century paintings and sculpture (Fig. 11). Upstairs there are three bedrooms. After spending a night in one of the guestrooms (Fig. 12), in which hangs a portrait of John Gordon, a gift from descendants, Morrison H. Heckscher, the former chairman of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote to me: “I know of no more comfortably authentic, untouched, all original house in America.”

Some years ago I had acquired at auction all three of Humphry Repton’s folio volumes—Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening (1794), Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803), and Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816). These fascinating books are composed of text and pictures that explicate Repton’s preferences in the designs of parks and gardens. I was immediately struck by the resemblance of Repton’s designs to the landscape of the Gordon-Banks house.

Humphry Repton was born in Bury St. Edmunds in April 1752 to well-to-do parents. His father, John Repton, envisioned a business career for his son, and when Humphry was sixteen John secured a position for him at a prosperous textile house. He remained with the firm for five years, but it appears from his recollection of the period that he was more concerned with his own apparel than with the textiles he was hired to purvey. “In those days of my puppy-age every article of my dress was most assiduously studied, and…I recall to mind the white coat, lined with blue satin, and trimmed with silver fringe, in which I was supposed to captivate all hearts.”1 The heart he succeeded in captivating belonged to Mary Clarke, and he proposed when he was eighteen. Due to parental pressure the engagement endured for three years, and they married at last in May 1773.

After the death of his parents in 1778 Repton happily relinquished his business career. He bought Old Hall in Norfolk, a seventeenth-century manor house, and relished the life of a country gentleman, overseeing his farm and working in his garden. However, with his increasingly numerous progeny, he realized his income was inadequate. He sold Old Hall and bought a cottage in Essex in the oddly named village of Hare Street. He tried his hand at a variety of occupations: as private secretary to a distinguished friend, as a writer of essays and art criticism, and as a playwright. None of these provided a sufficient income. One restless night in the summer of 1788 it suddenly occurred to him that he was already prepared to practice landscape gardening. His lifelong interest in horticulture and architecture, his talent for writing and drawing, and his acquaintance with prosperous members of the aristocracy were all assets. Capability Brown had been dead for five years, and as no one of comparable stature had appeared. Repton was convinced he was singularly equipped to replace the master.

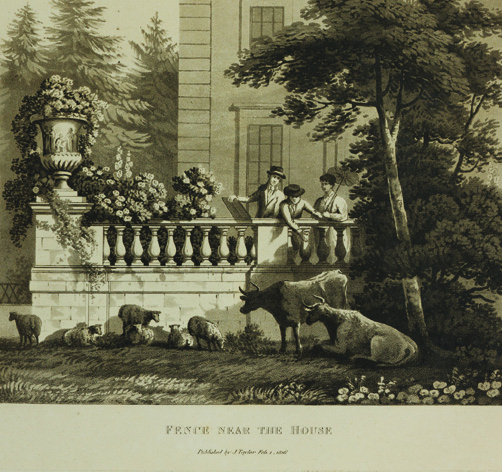

Repton genuinely admired Capability, referring to him as “the immortal Brown,”2 and he learned a great deal by studying his impressive achievements. They both designed picturesque parks with gently rolling hills, vast lawns, strategically placed trees and shrubs, and a stream or lake. Despite their similarities, Repton differed from Brown on certain significant issues, and he emphatically denounced what he regarded as Brown’s defects. For instance, Brown had insisted that the park extend right to the front door of the mansion, and he eliminated any trace of formal gardens around the edifice. Repton ridiculed “that bald and insipid custom, introduced by Brown, of surrounding a house by a naked grass field.”3 He wrote, “If there be any part of my practice liable to the accusation of often advising the same thing at different places, it will be true in all that relates to my partiality for a Terrace as a fence near the house…that line of demarcation betwixt art and nature…betwixt the garden and the park; betwixt the ground allotted to the pleasure of man, and that to the use of cattle.”4 In contrast to Brown’s aversion to formality, Repton insisted on a terrace framed with a balustrade (see Fig. 6) or “clipt hedge,”5 and he frequently designed a series of formal gardens in the vicinity of the house.

Once Repton determined to practice landscape gardening for profit he wasted no time launching his career. His first commission in September 1788 was a 112-acre estate at Catton on the outskirts of Norwich. It was for his third commission in March 1789 that he prepared his first so-called Red Book. Brandsbury was a modest property near London, one of several domiciles belonging to Lady Salusbury, an imposing widow often surrounded by her six pet dogs. Bound in red leather, the Red Book proved to be a brilliant marketing device. Repton produced one for most of his subsequent commissions. When he was invited to recommend what were called “improvements” at an estate, he would spend several days there, surveying the property, and he would eventually present a Red Book to the owner. The books were composed of a handwritten text, explaining in detail his suggested improvements, and illustrated with his watercolors. The pictures were often unflattering representations of the existing scene, to which he attached a flap; when the flap was opened, uncovering a large portion of the picture—lo and behold!—there was an irresistible depiction of a transformed landscape if Repton’s improvements were implemented.

In contrast to the relative modesty of his early commissions, in 1790 Repton was engaged by the duke of Portland to improve his nine hundred-acre park at Welbeck in Nottinghamshire, and, in 1791 the prime minister, William Pitt (1759–1806), retained him to design the gardens at Holwood, his seat in Kent. Pitt’s friends and supporters discovered Repton, and his reputation soon spread all over England. In her novel Mansfield Park Jane Austen devised a scene that attested to his fame. James Rushworth, a young gentleman of means, is deploring the condition of the estate Sotherton Court.

“I never saw a place that wanted so much improvement in my life; and it is so forlorn I do not know what can be done…I hope I shall have some good friend to help me.” “Your best friend on such as occasion,” said Miss Bertram calmly, “would be Mr. Repton, I imagine.” “That is what I was thinking of…I had better have him at once. His terms are five guineas a day.”

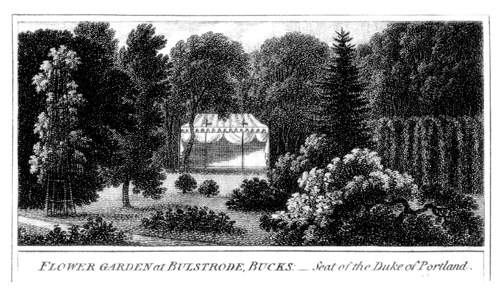

Despite some frustrations, in the first decade of the nineteenth century Repton achieved major successes. For the Woburn Abbey estate in Bedfordshire of his most valuable patron, the sixth duke of Bedford, he created a dazzling series of formal gardens: a rosary, American and Chinese gardens, an arboretum, and a menagerie, among others.

Now, when I stand on my porch and look over the terrace and “clipt hedge” to the expanse of lawn planted with trees and shrubs and, beyond, to the lake, I think of Repton. I walk down a slight incline to the formal garden with a nineteenth-century marble fountain (Fig. 13) and continue on to a pool and a pavilion with a striped canopy (Fig. 15). Strolling through an opening in the holly hedge surrounding the pool, I pause at a gazebo that overlooks a boxwood maze (Fig. 16) before entering the flower garden with its roses and peonies (Fig. 17). I appreciate the series of well-designed gardens—and, again, I think of Repton.

Reading more about him in preparation for writing this article, I was surprised to learn of Repton’s considerable influence on landscape architects in the United States in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In his very successful book, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1841), Andrew Jackson Downing described Repton as “one of the most celebrated English practical landscape gardeners”6 and quoted extensively from his writings. Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) was also a devotee of Repton, recommending his work to young landscape architects who asked his advice. The most serendipitous revelation, thanks to a friend’s research, concerned the educator Frank Waugh (1869–1943). In 1902, with an academic background in horticulture, Waugh joined the faculty at the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts) in Amherst; and there he established a department of landscape gardening, the second in the United States. Waugh, like Downing and Olmsted, was an advocate of Repton’s work. In his book The Landscape Beautiful, Waugh wrote, “the extravagances of Brown and his immediate imitators had been succeeded by the practical common sense and masterful genius of Repton,”7 and in recommending Repton’s Observations he commented, “This is the most valuable of early works on the practice of landscape gardening. Its instructions are still of great value.”8 Waugh not only praised Repton in his books and articles, he discussed his theories in his lectures.

William Pauley, who, with my father, designed the grounds of the property in Newnan, earned a master’s degree in landscape architecture from the Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1918. Since Waugh was his instructor, it seems likely that Pauley absorbed Repton’s principles of landscape gardening in the two years he spent at the college. Pauley moved to Atlanta in 1919 and in 1923, when he opened his own practice, he was the only professionally trained landscape architect in the state. Five years later my father retained his services. Thus, Repton’s theories may well have influenced Pauley’s designs for the Gordon-Banks landscape, and his precepts are still respected here.

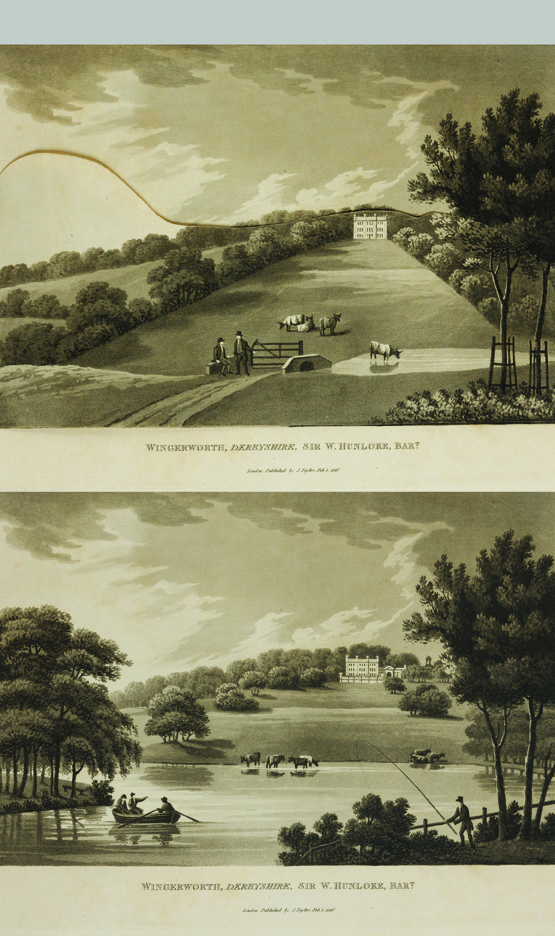

When I was perusing Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening I was struck by the similarity of the site of Wingerworth in Derbyshire to my property in Newnan, but I was dismayed to note that aspects of my landscape resembled the “before” illustration of Wingerworth’s park (Fig. 18a). In the 1930s and 1940s Pauley planted trees and shrubs that had grown and merged to create a pair of vegetative masses framing the lawn. In an effort to replicate the picturesque effect of Repton’s “after” illustration (Fig. 18b), I took his advice, removing trees and shrubbery to open the massive rows that he described as “puerile attempts at mock importance…not worthy to be retained”9 and planted several widely spaced elm trees and a small grove of fruit trees on the lawn (see Fig. 19). Still a work in progress, I believe that a well-preserved neoclassical house from the 1820s deserves a Reptonian landscape.

Special thanks to Lieutenant Colonel Thomas M. Lee, who was inestimably helpful to me in writing this article.

WILLIAM NATHANIEL BANKS, a writer and lecturer on American art and architecture, is a frequent contributor to Antiques, most often writing about historic towns and (other people’s) historic houses.

1 Quoted in Edward Hyams, Capability Brown and Humphry Repton (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1971), pp. 117–118. 2 Humphry Repton, Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening (London, 1794), introduction, p. xiv. 3 Humphry Repton, assisted by J. Adey Repton, Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening…(London, 1816), pp. 38–39. 4 Ibid., p. 8. 5 Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London, 1803), p. 126. 6 A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (New York, 1841), p. 268. 7 F. A. Waugh, The Landscape Beautiful…(Orange Judd, New York, 1910), p. 160. 8 F. A. Waugh, Landscape Gardening…(Orange Judd, New York, 1905), p. 147. 9 Repton, Fragments, p. 61.