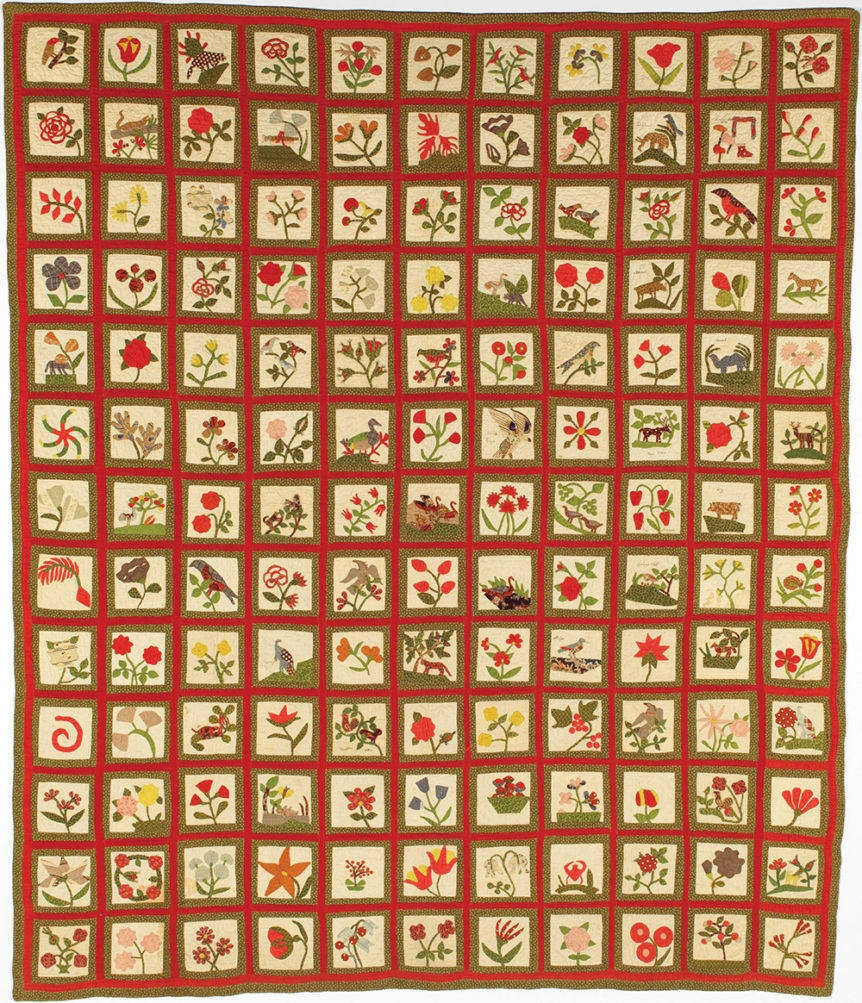

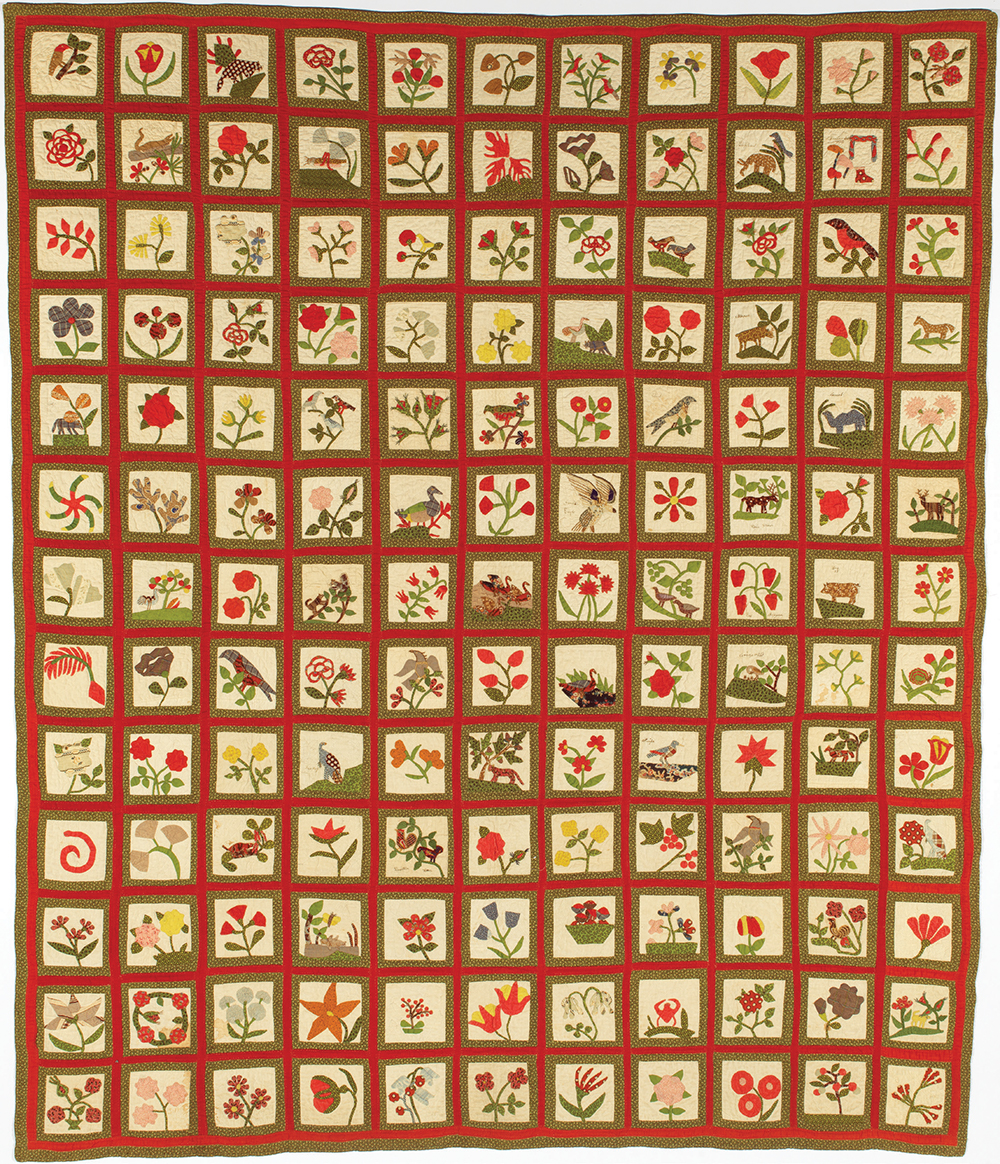

Fig. 1. Album quilt, American, c. 1850. Cotton, pierced and appliquéd with quilting, 87 ¼ by 74 ½ inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection; photographs are courtesy of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California.

In 2016 the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens opened the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing, an 8,600-square-foot addition to the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. The new wing, designed by Frederick Fisher and Partners, features selections from the Fielding Collection of Early American Art, an esteemed group of American works from 1680 to around 1870. The Fieldings began collecting in earnest in the early 1990s to furnish their historic home in coastal Maine. Now numbering in the hundreds of objects, the collection includes important painted portraits, furniture, needlework, painted boxes, quilts, and related decorative arts. The collection also focuses on beautiful objects made for everyday living, mostly by rural New Englanders: lighting devices, fire buckets, metal implements, scrimshaw, handwoven rugs, ceramics, and weather vanes together evoke the rustic yet refined world built by the hands of early Americans. More than two hundred of these objects currently grace the new wing, a significant number of which have entered the Huntington’s permanent collection as gifts of the Fieldings.

In its rich diversity, the Fielding Collection offers a rare opportunity to explore early American history through objects made for everyday use and through images of the people who used them. Many of these people—the makers as well as the users of the objects on display—were women and girls. The opportunity to highlight the experience of womanhood in American history augments the stories we can tell through American art at the Huntington. A closer look at a few of these rare objects gives a taste of what one can see in person in the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing.

A helmeted figure commanding a horse-drawn chariot; a woman threshing wheat at harvest; and a bounteous explosion of flowers and leaves: these are just a few of the exuberant details in a remarkable sampler from around 1790 in the Fielding Collection (Figs. 2, 2a). Typically made by girls between the ages of eight and eighteen and subsequently framed and displayed in the home, samplers count among the most important material expressions of femininity in early America.

Figs. 2, 2a. Sampler by Eunice Hooper (1781–1866), Marblehead, Massachusetts, c. 1790. Silk on linen, 23 by 23 ½ inches.

This example belongs to an important group of samplers made in the last decade of the eighteenth century in Marblehead, Massachusetts, which was then a prosperous hub of sailing and commerce. Samplers in this group often feature fanciful scenes and images of everyday life against densely embroidered black backgrounds. This example proudly proclaims its maker in two lines of text at the top of the composition: “Workd, by Eunice Hooper in The Ninth Year of her Age.” Hooper’s parents, Samuel and Elizabeth Russell Trevett Hooper, were prominent residents of Marblehead, which would have afforded young Eunice the opportunity to learn needlework from a skilled teacher. Her extraordinary command of the medium—evident in the two-story Georgian house masterfully shown in side view—marks this sampler as an important example of New England needlework.

Figs. 2, 2a. Sampler by Eunice Hooper (1781–1866), Marblehead,

Massachusetts, c. 1790. Silk on linen, 23 by 23 ½ inches.

But such heights of accomplishment in needlework didn’t end at samplers for young women in early America. Indeed, the skills they learned in their early schooling were intended to be useful to them and their families for their whole lives. Women in this period were expected to spin yarn, weave, and sew cloth, in addition to the other domestic labors endemic to running a home: cooking, cleaning, childcare, gardening and tending the family’s animals all fell under the purview of women. Still, some found time to create remarkably personal expressions of this care in handmade objects.

Fig. 4. Needlework pocketbook by Elisabeth Fellows, American, 1776. Wool on linen, cotton tape trim; height 5 ¼, width 9 ¼, depth 3 ½ inches.

Consider, for instance, a needlework pocketbook made by Elisabeth Fellows in 1776 (Fig. 4). Pocketbooks like this one were used by both men and women during this period. Featuring tripartite geometric patterning in various blues, greens, and pinks, the pocketbook was worked in wool yarn on a linen substrate. The careful stitching of Fellows’s name in green block letters atop the front panel drops the final “S” into the triangle of blue just below. The date notation offers a clue to the intent of the maker: pocketbooks were often made by women as gifts to their husbands or other family members. It is possible that Fellows stitched this one for her husband, perhaps as an object of love for him to carry into the Revolutionary War.

Women in early America often expressed their affection in this way—through finely handcrafted objects that fulfilled utilitarian purposes. You can see this impulse, too, in a particularly spectacular album quilt in the Fielding Collection (Fig. 1). Made around 1850 in New York, the quilt comprises a grid of 143 blocks, each filled with a floral or animal motif. Some of these individual blocks are schematic and abstract, while others feature highly detailed piecing, embroidery, and even have individual titles handwritten in ink. One block, bearing the inscription “Crain’s Nest,” portrays a crane perched on a green hill with three small beaks peeking out over the nest’s edge, waiting for their meal. The crane’s body is made from appliquéd brown-striped cloth, while the legs, feet, wings, and beak are depicted through two-tone brown stitching. Other panels show truly accomplished passages of complex embroidery, as in the image of a “great eagle.” The quilt was almost certainly developed through the collaboration of several skilled female quiltmakers; a variety of approaches are evident here, each manifesting a distinct personality.

Fig. 3. Niagara beadwork hat, Iroquois, c. 1870. Beadwork on black cloth and velvet; height 3 ¾, length 11, width 6 ¼ inches. Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, gift of Jonathan and Karin Fielding.

Other objects of fine craftsmanship were created by women in early America for commercial purposes. A glengarry cap from Niagara Falls, New York, is one example (Fig. 3). In the early nineteenth century, a lively economy began to emerge around travelers to Niagara Falls; local Native American tribes responded in part by making objects that appealed to the tourist trade. The form of this cap derives from a traditional Scottish Highland manner of dress, which was familiar in this region through military uniforms worn by British soldiers in Canada. Queen Victoria popularized the Scottish style in Britain and its colonies in the 1850s by dressing her sons in elements of Scottish costume. Iroquois and Wabanaki women elaborated on the basic form of the glengarry cap, applying lush surface embroidery along the top and sides. Often, such hats were embellished with beadwork—like the one in the Fielding Collection—and variously with colorful ribbons, velvet, and moose hair. They were worn by Native Americans and tourists alike. The long green stem of the floral form on this example marks it as Iroquois in manufacture.

Fig. 5. Portrait of a Woman with a Bowl of Cherries, probably Connecticut or New York, c. 1770–1780. Oil on panel, 28 by 23 inches. Photograph © 2017 Fredrik Nilsen.

In fact, the long and sturdy stem offering a copious bounty might be the perfect visual metaphor for this collection of early American material. We see it again in an important early portrait of a woman with a bowl of cherries, dating from around 1770 to 1780 (Fig. 5). Likely painted in Connecticut or New York, this picture shows a woman sheathed in a black dress with white lace trim—perhaps marking it as a marriage portrait—and a neatly tied blue bow across her chest. Her right hand clutches a few cherries over a red bowl filled with the fruit, while her left holds a bunch aloft, almost proffering them to us. Her hair primly gathered behind her head, she meets our gaze with wide-eyed, almost quizzical directness. Bearing some resemblance to colonial portraits of Dutch landowners who populated the Hudson River valley, this picture is somehow less solemn, more hopeful than those. With its overtones of fertility and plainspoken, unabashed beauty, it captures the spirit of the age. At the same time, like the rest of the Fielding Collection, it offers an opportunity to study and appreciate the many women, named and unnamed, who served as the sturdy stem to early America’s copious bounty.

CHAD ALLIGOOD is the Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California.