You can find it on Wikipedia, read about it at on the website connecticuthistory.org, see it in the dizzy video Hidden in Plain Sight, and dip into any number of excited online accounts of the 1930 Chick Austin House in Hartford, Connecticut. It’s a place that seems to get rediscovered nearly every other day by people entranced by its architectural sleight of hand. But until it reopens for tours, the Chick Austin House is best encountered on the Wadsworth Atheneum’s website, where images of its meticulous restoration by the museum have been pulled from Eugene Gaddis’s 2007 book Magic Facade: The Austin House.

After you have gazed in wonder at its painted wood exterior modeled on the sixteenth-century Villa Ferretti near Venice, giggled at its amusing dimensions (eighty-six feet wide but only eighteen feet deep), marveled at the perfectly conceived rococo interiors on the ground floor and the sleek mid-century modern dressing room and baths upstairs, questions may arise. Perhaps it is best to engage the most challenging of them: how could this folly built and furnished at huge expense during the Great Depression possibly have mattered then—or in 2020 amidst a plague, environmental catastrophes, and in a badly fractured republic? I am confident that A. Everett “Chick” Austin Jr. would have welcomed the question. Never one to turn away from a challenge, he once observed: “The house is just like me, all facade.”

Should we take him at his word? I wouldn’t, and I doubt he wanted us to; it was just one more provocation from a fellow who knew that if you wanted to go deep you first had to provoke, entice, put up a front. He was, after all, a magician who began performing in childhood and continued to do so as an adult touring New England and earning his membership in the International Brotherhood of Magicians while also running a museum that seduced the public to modernism by staging balls with sets and costumes by artists like Pavel Tchelitchew and Alexander Calder.

So, yes, understanding the house means understanding the man who created it, the man who at twenty-seven became acting director of the Wadsworth Atheneum (later its director) and almost immediately took the country’s oldest public art museum from Wallace Nutting Pilgrim furniture to the most talked about arts institution in the country—famously the first to hold a major Picasso show, the first to stage a performance of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts with its all Black cast, the first to do many modern things that eclipsed, for awhile, the nascent Museum of Modern Art, while also acquiring works by Fra Angelico, Goya, and Daumier, among others. It also means considering Austin’s wife, the circumspect Helen Goodwin Austin, who embarked on an adventure that took her from Hartford society into unfamiliar realms— not just that of European modernism, but the surprising adventures of an errant, profligate, bisexual husband . . . and the creation of this house.

Fig. 5. The dining room with its rococo bed niche and reproduction Italian silk brocatelle in a baroque pattern.

Fig. 6. View through the living room’s carved rococo doors showing the Neapolitan Directoire settee, c. 1790, in the music room.

How did he do it? It was not all facade, far from it. The biographical details can be found in Eugene R. Gaddis’s excellent Magician of the Modern: Chick Austin and the Transformation of the Arts in America, now sadly out of print. After reading it you will want to supply your own understanding of this man. To me, Chick Austin is part Peter Pan, part J. Thaddeus Toad, and to mix things up, part Icarus. He spent wildly, he aimed high, and he captivated everyone who knew him, warming the Anglo-Saxon souls of Hartford’s grandees while introducing patrons everywhere to stars from Buckminster Fuller to Bette Davis. As much as he looked to Europe for most of the art he admired, both ancient and modern, he was above all an American original in the Emersonian mode. “Build . . . your own world,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, establish “an original relation to the universe.” And so he did. Emerson begat Whitman begat Chick Austin? Yes, I think so.

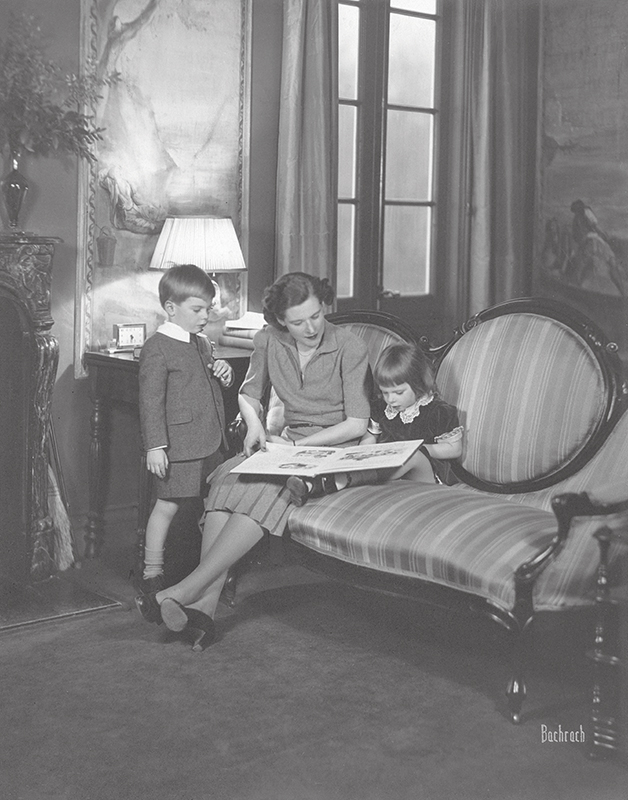

What about the house? Palladian, rococo, European modernist, and slightly nuts—only an American could have created it. It has several seemingly incompatible personalities: a party house, a stage set, a comfortable nest designed by and for a couple who did not plan on children (there was already a child in the house, Chick). And yet they did have two children, who scribbled on the walls upstairs and stayed with their mother as their father roamed from Hollywood to Sarasota, Florida—where he made the Ringling Museum into a world-class institution—to Europe, and back again to Hartford. They loved him. Everyone did. That’s how he got away with it all . . . that and something else: the good looks, the antic spirit, the humor and adventurousness all rested on a solid foundation. His scholarship, lectures, and his appeals to the Wadsworth for acquisitions of everything from Caravaggio to Balthus were brilliant, fact-based, and aesthetically well reasoned.

Fig. 8. This view of the living room shows the art deco coffee table and the Italian settee and bergères bought in Hollywood, set against wall panels painted in Turin in the eighteenth century.

Fig. 9. Music room, with the art deco Steinway spinet purchased in 1939.

The house, too, is far deeper than its shallow eighteen-foot dimension. It is not a “machine for living,” as Corbusier would have it, but a set for delighting, welcoming, and, in answer to the question about its relevance then and now, providing a respite from the world outside, from history past and present. I am not especially drawn to either rococo furnishings or mid-century modernism though I admire both from a distance, and yet I have twice toured the Austin house wishing I’d been a frequent guest. You can feel the excitement in the dining room, where, seated at the beautifully appointed table, you would have gazed upon the slightly cuckoo rococo alcove (originally a bed niche) carved with cherubs, flowers, and leaves. It’s an unusual touch but characteristic of Chick Austin’s approach to life and art: beauty with a hint of humor. To me that’s a winning combination and a rare one.

The living room gives you everything we prize in modernism—space and light—without modernism. It is large, long, and narrow so the windows on either side flood it with light, or would if the curtains could be pulled back without risking damage to the fabrics and the eight large tempera panels painted in Turin in the eighteenth century that line the walls. I can easily imagine myself here, too—before dinner, after dinner, and on into the night.

I’m skipping over the international style dressing room and baths upstairs. They were revolutionary, of course, handsomely done, and perfectly suited to their purpose. They remind me of something else I admire about Chick Austin and seldom encounter today—a person whose appreciation of arts past and present admits of no hierarchy.

Fig. 12. The master bedroom is hung with reproduction eighteenth century Alsatian toile de Jouy.

Fig. 14. Genoese Louis XIV paint-decorated commode, c. 1750, and a richly carved and gilded Venetian looking glass, c. 1780, in the master bedroom.

By the time it was over in Hartford, by the time Chick Austin had staged one too many adventures that courted national acclaim but local disdain (especially in the Hartford press), he hastened his exit from the museum in 1943 by using its Avery theater to produce and star in ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore by the seventeenth-century English playwright John Ford, taking the role of Giovanni, the brother who insists on the rightness of his incestuous affair with his sister, Annabella, eventually murdering her and impaling her heart on his sword to save her honor. Ford’s play was not meant as a popular entertainment in the early seventeenth century; originally a piece for an aristocratic audience, it was and is difficult to understand. For a play with so provocative a subject it has no convincing moral center and is thus rarely staged. When it is produced, it is usually set somewhere distant in time or place as in the Public Theater’s 1992 production set in Mussolini’s Italy . . . as if that helps to clarify things.

Why, as the country was fighting World War II, did Chick Austin put on and star in this overripe play? Let’s assume he knew it was time to go, time to leave Hartford and the house that encapsulated so many of his seemingly contradictory enthusiasms and to which he would in the end return, dying there in 1957. Someone, perhaps his biographer Eugene R. Gaddis I like to imagine, has placed a framed depiction of the tragic Annabella from Chick’s production of ’Tis Pity in the foyer of the house, a memento mori of sorts.