It’s Armory Week in New York, and while that means partying at the eponymous Armory Show (which, somewhat confusingly, has been quartered at Piers 90 and 94 for the past twenty years) for contemporary art enthusiasts, antiques lovers will be getting their kicks across town, where more than two hundred dealers in rare books, maps, photos, memorabilia, and such have gathered for the sixtieth annual New York Antiquarian Book Fair—the most important event on international book dealers’ calendar—at the Park Avenue Armory.

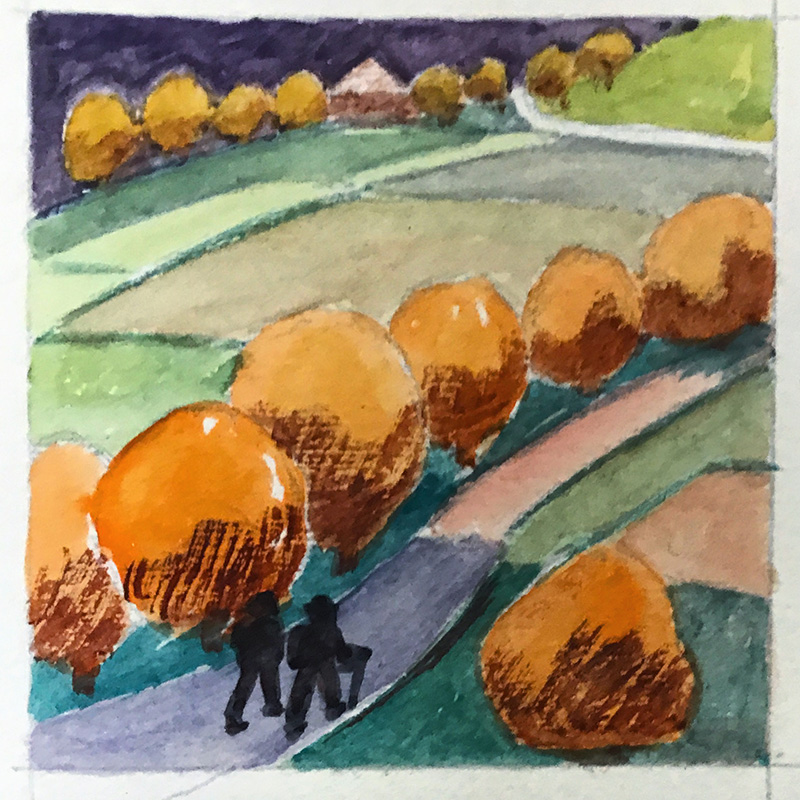

The usual suspects—rubricated Bibles, Renaissance-era anatomy textbooks, and geographically inaccurate Mappae Mundi—predominate, but it was a debutant that drew our eye this year: a collection of keenly observed and confidently composed crayon, oil pastel, and watercolor/body color illustrations of Switzerland during the war years, 1940–1946. It’s being offered by Brooklyn’s Honey and Wax Booksellers, and the hook (if the scenes alone fail to fascinate) is this: No one knows who the artist was, where exactly he or she was active, or how these scenes were chosen for depiction. Most puzzling of all, each image is captioned with strange words that aren’t consistently identifiable as coming from Swiss, German, Esperanto, or any other language spoken in the Alps.

The gallery’s founder, Heather O’Donnell, has invoked the hive mind of the Internet to help solve the mystery of what she tentatively calls “Europa Redux,” creating an Instagram account where she posts images from and information about the series. It’s fascinating to peruse comments left by users from across the world, some of whom detect whiffs of Swiss-German, Romansch, or a Lombard dialect in unfamiliar words like “Komptoir,” “ruah,” and “Mittingsaia.” These online sleuths are also quick to point out thematic patterns. Landscapes, constructivist-like art, and portrayals of people working abound in the series, and human characters depicted once do not reappear, all clues to the work’s underlying logic. Some commentators see Europa Redux against the backdrop of other mysterious European codices, like the fifteenth or sixteenth century Voynich Manuscript, an encyclopedia or magic book of plants, astrological signs, and anatomically correct nudes, accompanied by undecipherable commentary; and the surrealist Codex Seraphinianus drawn by Luigi Serafini, an ultramontane contemporary of the Europa Redux artist.

Our two cents? The faultless compositional strategies employed by the artist, taken together with the fact that early panels are clearly copies of European tourist brochures, would seem to indicate the hand of either a professional illustrator or a copyist. And to our linguistically untutored ear the reasoning of @robertgoulding rings probable: “The fact that [the words] don’t seem to conform to any language or phonemes in any language is suspicious. . . . Suggesting to me that they are either a cipher, or there is some method or algorithm used to generate the words.”

We encourage readers (especially code breakers) to check out @europaredux and help solve the mystery. If you’re game, go see it in person at the armory before some lucky buyer snaps it up.