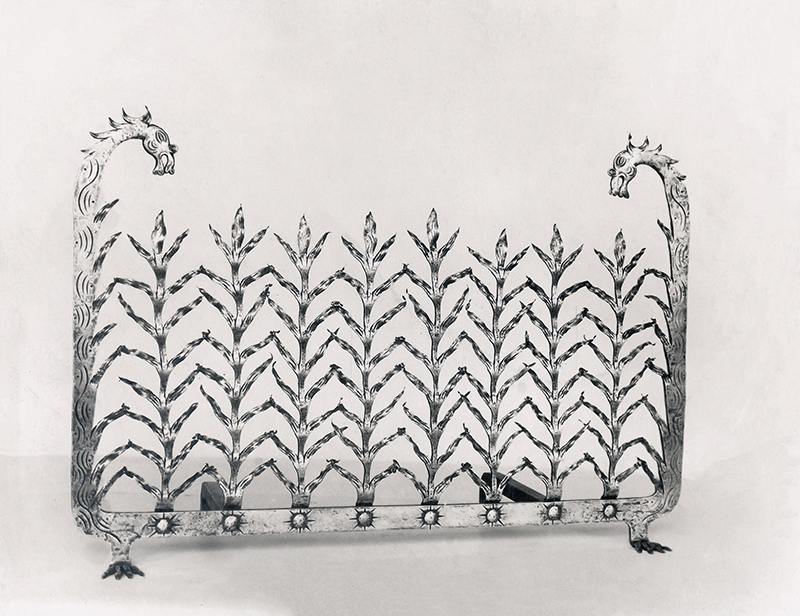

Genuine discoveries in the twentieth-century design market are quite rare. With traditional research and scholarship and the explosion of online resources, it often seems like there are few great things left to be unearthed. That surmise was called into question when an important firescreen by Samuel Yellin appeared in a recent auction at Samuel T. Freeman & Co. Though it was known to the public through a historic photograph, its presentation at Freeman’s marked a first material encounter with the work for many but its status as among the couple most significant works ever executed by the Philadelphia ironworker was utterly unknown. Here we will excavate the firescreen from its previous misidentifications and reset it within its original context of manufacture and exhibition.

This firescreen is best understood as a sculptural object unencumbered by utilitarian concerns; truly, a masterpiece of pure design. The firescreen was misidentified decades ago by Jack Andrews in Samuel Yellin: Metalworker—the work was not made for “R. T. Walder” (this client name does not exist in the Yellin archives), but instead for the legendary American architect Ralph Thomas Walker. The sticker on the reverse of the period image in the Samuel Yellin Metalworker Archives at the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania reads “Wrought Iron Fire Screen Designed and executed by Samuel Yellin for R. T. Walker; X-2149; 1929.”

Walker designed what is widely considered the first art deco skyscraper in the United States—the Barclay-Vesey Building—which led to a generation of skyscrapers using the set-back principle. Frank Lloyd Wright called him “the only other honest architect in America.” When the American Institute of Architect created the Centennial Medal of Honor for him, the New York Times reported that Walker was the “Architect of the Century.” Walker was a dear friend and valued collaborator of Yellin. They worked together on major projects including the Brooklyn Edison Company headquarters (1923–1927); the Barclay-Vesey Building in New York (1925–1926); various New York Telephone buildings (1926-1929); and the Salvation Army Territorial Headquarters (1929) in New York.

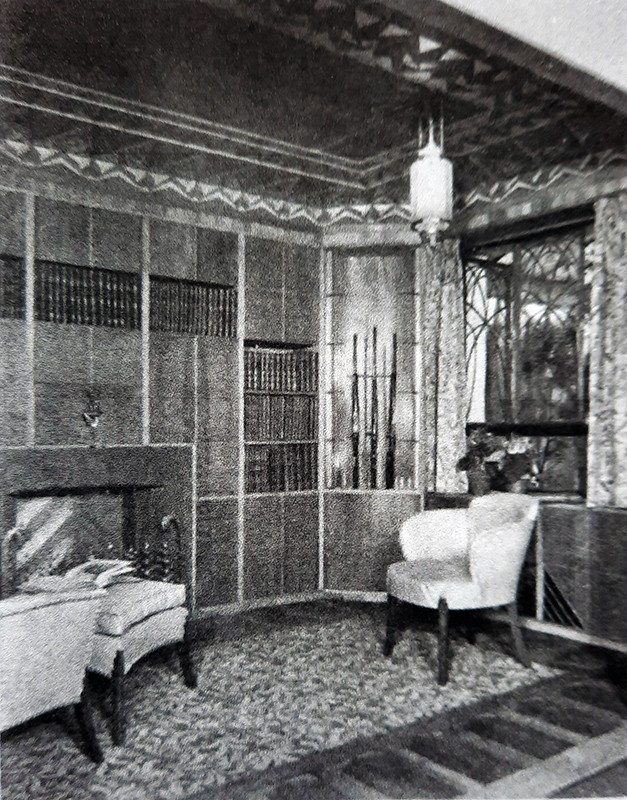

Their collaboration on this singular firescreen is among the high points of Yellin’s career. This imaginative and exquisite form was designed specifically for the Exhibition of Contemporary Design in American Industrial Art, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from February 12 to March 14, 1929.1 Its original placement within an installed room meant that its pure design could be expressed with no concern for usability (there is little to block sparks or embers from a fire). The other architects in the exhibition included Joseph Urban, Eliel Saarinen, Eugene Schoen, Raymond Hood, Ely Jacques Kahn, and John Wellborn Root Jr. All of the architects in the Met exhibition were known for their work in modernist and art deco styles.

In addition to publication in various Metropolitan Museum volumes, Ralph Walker’s installation, “Man’s Study for a Country House,” was illustrated in the Western Architect. The firescreen was variously reported in period publications as the design of the architect or as a collaboration between Walker and Samuel Yellin. Yellin’s engagement by Walker on the project seems to have been formalized by November 14, 1928, when the architect thanked the ironworker “for agreeing to collaborate . . . on the Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition.”2 He sent to Yellin “a rough suggestion of the design,” which he hoped would get the ironworker’s “mind working along the lines” of his ideas. On November 24, 1928, the architect addressed the ironwork regarding the “Metropolitan Museum of Art Exposition,” enclosing “a blue print of drawing No. 101, relating to the room,” and encouraged Yellin to get to work on the piece as quickly as possible. Walker mentioned andirons for the same room, but the design or execution of those works is undocumented and seems unlikely. Regarding the firescreen design, Walker begged of Yellin “any suggestions” he might make for improving the design.

On November 30, 1928, Yellin assured Walker that he was “getting busy now, since there is very little time left.” Yellin executed a “fragment of iron made for the flame firescreen,” which he brought to New York in early December to show Walker, but alas found that the architect was away in Chicago. He resolved at that time that he would not show the architect any further drawings nor attempt to show him the sample section in iron, instead vowing to “go ahead and make the firescreen . . . ready for a good cussing out” by Walker should he be displeased with the product. Within just a few days, the architect endorsed the “procedure as far as the firescreen is concerned,” which plan he called “very agreeable.” He told Yellin to “go ahead merrily, with great confidence” that the work would be “very, very handsome, and would not be better for any criticism that [Walker] might offer.”

Following another plea on January 30, 1929, that he execute and deliver the ironwork to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yellin heard directly from the Department of Industrial Relations on February 2. Richard F. Bach, the director of the department, solicited Yellin to “anticipate the last minute rush” of installing the various rooms in the exhibition, suggesting that delivery “within the next few days . . . would be of great advantage, especially since the press view has been scheduled for February 7th.”3 Delivery to Ralph Walker at his offices at 101 Park Avenue in New York was confirmed by the architect on January 31, 1929. Instead of sending the work directly to the museum, Yellin had sent it to the architect, who conveyed it to his installed room.4 Walker addressed Yellin directly on February 9: “I have been so busy that I have not had an opportunity to express my appreciation of the beauty of the firescreen.”5 He told the ironworker that “it was put in place yesterday and adds a great deal of distinction to the room.” Walker stated further that he was “very, very pleased with it.”

The entire composition was conceived and executed as a unified structure and integrated design. Its effect is unusually expressive among such fireplace equipment by Yellin. The firescreen is stabilized from behind with billet bars and at the front with two four-toed feet. Above the feet, the frame ascends on its right and left side as incised bars with dragon-head finials; in between, a stunning row of eight vertical stalks arise with peeling leaves that resemble flames. One of the most unusual features of the firescreen is that there is no top side of its frame, thus liberating the uppermost register of leaf-flames. In order to secure the vegetation arising from the lower framing, many leaves are twisted or curled over one another to reinforce the horizontal stability of the composition. This creates a kind of mesh but the structure remains so fragile as to prevent any potential robust use. The intricacy and delicacy of the jewelry-like ironwork signals clearly that the object was meant only as an object of pure art, not a usable home implement. Consistent with the architectural style of Ralph Walker, the bold modernity and intrepid design of this firescreen place it at the apogee of Yellin’s work.

1Photograph of firescreen, job X-2149, SYMA; Western Architect, (Chicago: Western Architect, Inc.) Volume XXXVIII, 1929, pp. 35-38.

2Correspondence between Samuel Yellin and Ralph Walker is taken from copies in the collection of University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives [UPAA], Ralph Walker file: Letter from Walker to Yellin, 17 November 1928; Letter from Walker to Yellin, 24 November 1928; Letter from Yellin to Walker, 30 November 1928; Letter from Yellin to Walker, 7 December 1928; Letter from Walker to Yellin, 11 December 1928; Letter from Walker to Yellin, 30 January 1929.

3Letter from Richard F. Bach to Yellin, 2 February 1929, Ralph Walker file, UPAA.

4Delivery Receipt, from “SY Metalworker 5520-22-24 Arch Street Philadelphia” to “R.T. Walker, 101 Park Avenue, New York City,” One Wrought iron firescreen “received in good order” by Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker.

5Letter from Walker to Yellin, 9 February 1929, Ralph Walker file, UPAA.