Saltbox, adobe, shotgun. Each of these vernacular architectural styles conjures a corner of the country. So, too, do H. H. Richardson’s shingled summer villas in New England, Addison Mizner’s Mediterranean mansions in Florida, and the desert-embracing work of Richard Neutra in Palm Springs, California. When it comes to significant residential architecture in Illinois, the work of David Adler, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe immediately springs to mind. But the state is also home to the under-sung modern designs of architect Paul Schweikher. One of the most characteristic is the home and studio west of Chicago that the Denver-born, Yale-trained architect built in 1938 (Fig. 1). The long, lean structure’s profile and interior disposition reflect a highly personal approach to space, one that tapped into aspects of traditional Japanese design and the hallmarks of the Prairie school of architecture.

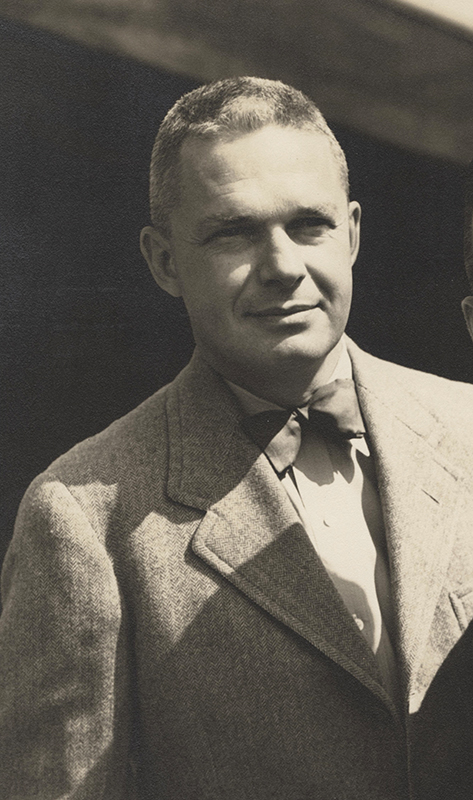

The son of musicians, Schweikher initially studied electrical engineering at the University of Colorado, where he met his future wife, Dorothy Miller, at a party. When Dorothy graduated from the University of Denver and headed to Chicago for a job as a medical laboratory technician, Schweikher followed. After working as a bookkeeper in a bank, Schweikher— who had demonstrated drawing skills as far back as high school—sought work as a draftsman and landed varying gigs at several firms, including that of David Adler, the country-house architect of choice for the city’s elite. While in Chicago, Schweikher studied at the Armour Institute of Technology (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) before moving on to Yale, where he earned a BA in architecture in 1929.

Back in Chicago (where he and Dorothy had married in 1923), Schweikher was employed by various architectural practices (including the offices of George Fred Keck and Philip Maher) before launching his own business in 1934. By then his work had been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and included in the Century of Progress Exposition held in Chicago in 1933. Schweikher remained in the Midwest until 1953, when he was named chairman of the Yale School of Architecture (while there, he and Dorothy became friendly with artistteachers Josef and Anni Albers). Schweikher later headed the Carnegie School of Architecture in Pittsburgh, before retiring in 1968 to Sedona, Arizona, where he built a new home on a butte in red rock country and continued to practice.

Over the course of his career, Schweikher designed a number of private homes and churches, as well as a smattering of larger projects, including the Duquesne University Student Union. But the house he created for himself in Illinois remained one of his favorite works. Reminiscing about the house in the 1980s, the architect remarked, “It seemed to handle the material most knowingly of anything that I did before or after. It was knowledgeable, it was plain spoken, it fit the site, adapted well to human use.”1

Situated on several acres twenty-six miles from Chicago on what was once farmland, the Schweikher House (the initial plans for which he drew up at sea while returning from a visit to Japan) was first conceived as a three-room affair designed on a Tshape plan, with living quarters comprising the bulk of the arrangement and a roomy studio adjacent across a covered breezeway (Fig. 5). The Schweikhers welcomed a son in 1945, and several years later the architect added a modest bedroom to the main wing and also extended his workspace by appending a conference room that cantilevers off the drafting studio (Figs. 9, 10).

Fig. 7. The monumental grid above the large open hearth was made by laying the bricks with their shorter ends exposed. The black lounge chair was designed by Lawrence Peabody (1924–2002) for Selig and introduced in 1954. It’s paired with an ottoman from Ferrario’s, the St. Louis store of Martyl’s brother, Martin Schweig Jr. Photograph by Will Quam/Brick of Chicago.

Predating the now iconic Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe and conceived a year before Wright’s first Usonian home was built in 1937, the Schweikher House stands, not as a missing link, but certainly an under-appreciated landmark in early mid-century design. Seemingly simple yet richly articulated, it exudes both assurance and a sense of experimentation. Even today, when many of its attributes—the open plan, built-ins, the orientation to the landscape—are appreciated historically and as still viable modes of design, the house should be regarded as an envelope-pushing effort to re-imagine the American home.

Constructed of brick, redwood, Douglas fir, and then-new standardized-size sheets of plywood, the house expresses a deeply satisfying cohesiveness. Pavers run inside and out, amplifying that sense of aesthetic unity and underscoring the spatial flow. The color and texture of the materials and the orchestration of the interiors invest the home with a solid feeling of comforting enclosure, while strategically situated expanses of glass open it to artfully composed vistas. “One of the important things about Paul Schweiker’s architecture throughout his life is that he had a very unique sense of scale and proportion,” observes Arizona-based architect Will Bruder. “So when you are in the house there is something that is totally poetic, totally integrated.”

Fig. 10. The fireplace in the former conference room echoes on a smaller scale the pattern of the living room fireplace.

With its pronounced horizontality and relatively compressed massing, Schweikher’s home might easily be taken for one of Wright’s Usonian projects, the small, single-story houses the architect began producing in the mid-1930s. And while they share similarities (including deep eaves), Schweikher’s design sprang from a different motive, suggests Bruder, who knew the architect for more than twenty-five years and is the editor of the forthcoming book Paul Schweikher Architect, a 20th Century Master of Making and Materials (Hat and Beard Press). “The Usonian concept was very much about the idea of prefabrication and a system of modules,” he says. “Schweikher was much more about structure and elevation and matters of scale.”

While some architects and historians are aware of the property, it was only in the last few years that the public has been able to visit the house. After the Schweikhers departed for New Haven, it became the home of Alexander and Martyl Langsdorf. He was a physicist working on the Manhattan Project, and she was an artist who also designed the Doomsday Clock for the June 1947 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “The Langsdorfs always knew this was a very special house and they were very gentle with it,” says Dan Fitzpatrick, managing director and historian for the Schweikher House Preservation Trust. “They talked to Schweikher when they wanted to make any changes or repairs.” After Alexander’s death in 1996, Martyl remained in residence until she died in 2013. She established the Schweikher House Preservation Trust in 2009 and regular public tours commenced in 2018.

Schweikher received substantial press coverage throughout his career. In 1957 Architectural Review named him in a pantheon that included Louis Kahn, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, I. M. Pei, and Paul Rudolph, among others. But Schweikher wasn’t much of a self-promoter. He never displayed the cape-swinging swagger of Wright and never hooked up with developers or corporations to design large, headline-grabbing projects. When asked in a late-life interview to remark on his approach, Schweikher said: “I never really found nor formed a philosophy and many of my professional colleagues would probably agree. But one thing kept forming in my mind from project to project, and I guess I may have reinforced it by reading and re-reading Thoreau . . . that one should ‘simplify, simplify, simplify.’ I’m certain of this one thing, for good or bad: from project to project, in houses, in institutional buildings, and so on, it was a search for the simplest way to solve the problem. The design of a detail, the laying out of a plan, development of an enclosure, the elevations, I wanted to simplify.”2

Fig. 14. The sharply incised planar quality of the structure is clearly evident from the parking area in front of the house.

For more information on tours of the Schweikher House, visit schweikherhouse.org

1 The author wishes to thank the Art Institute of Chicago for access to an interview with Robert Paul Schweikher conducted by Betty J. Blum and compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, the Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings, Department of Architecture, the Art Institute of Chicago. © 1997– 2000 The Art Institute of Chicago, and used with permission. This is an edited excerpt from a longer interview conducted by Betty J. Blum in 1984 for the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, organized by the Department of Architecture at the Art Institute of Chicago. This quotation is from p. 212 of the excerpt. 2 Ibid., p. 142.

THOMAS CONNORS is a Chicago-based arts writer.