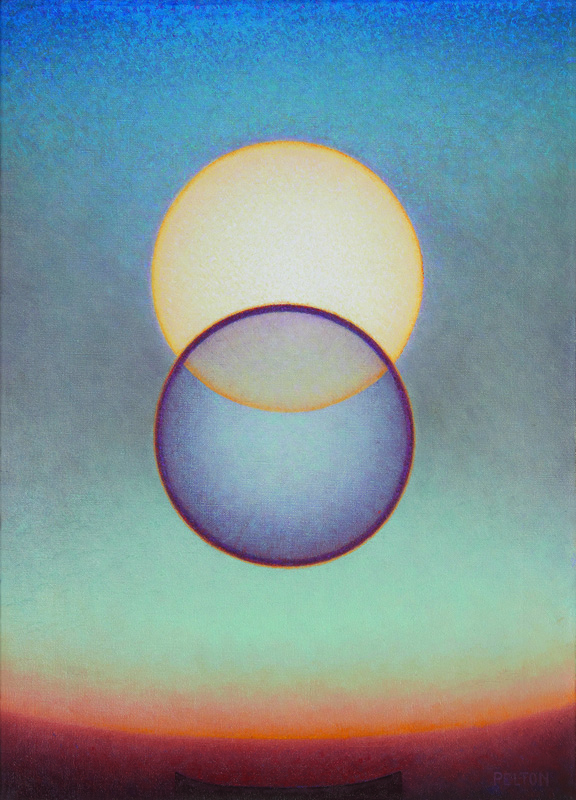

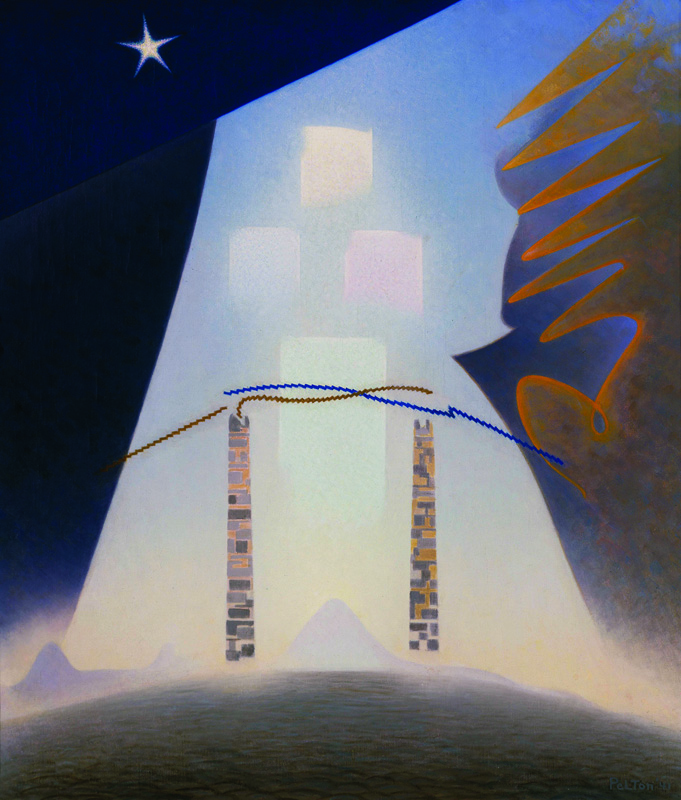

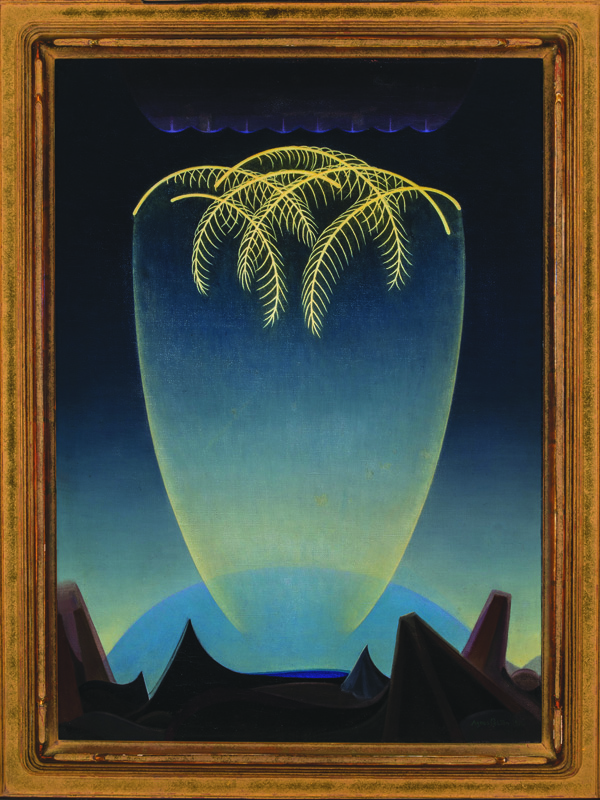

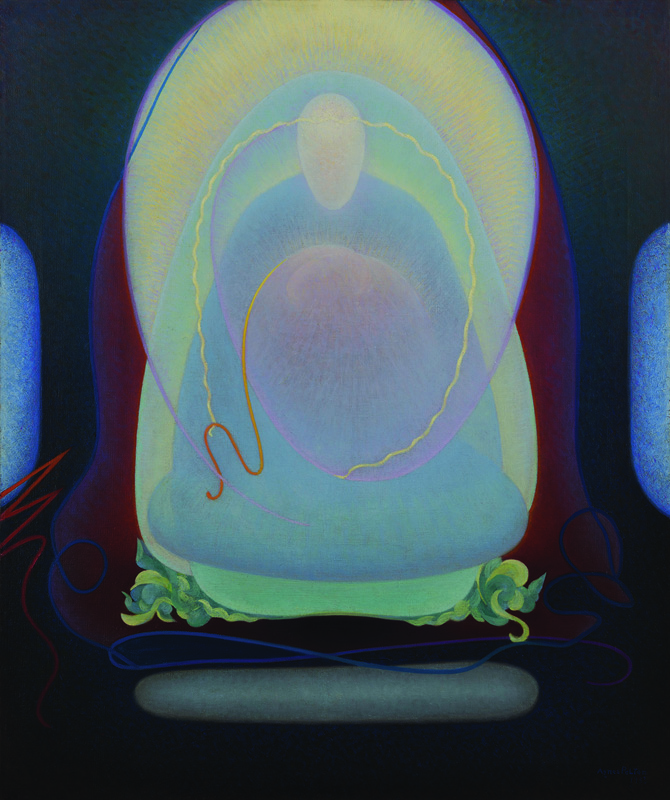

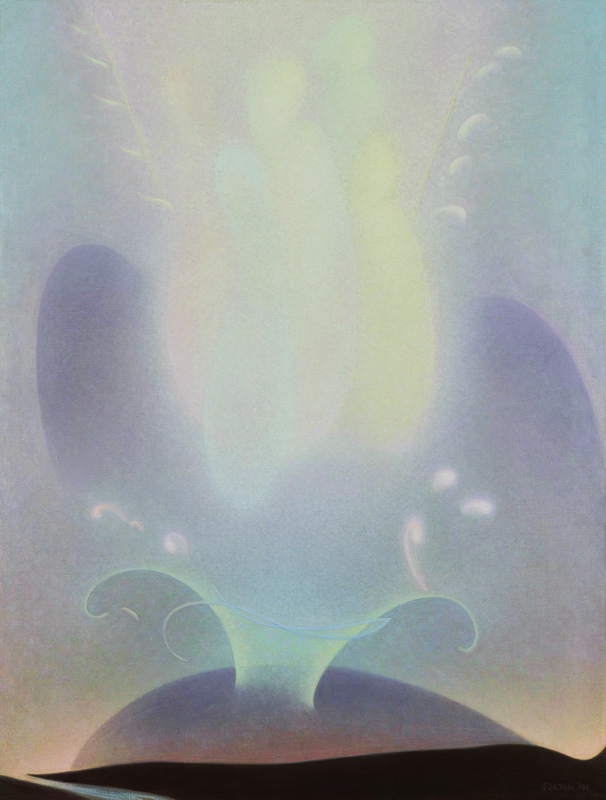

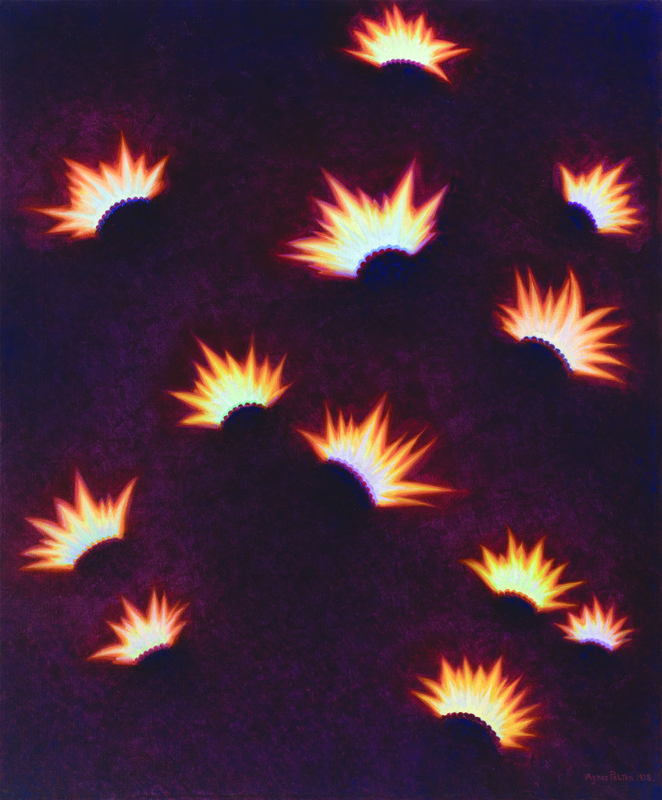

“They are records of inner visual experiences, bringing light out of darkness, or serenity out of oppression,” the avant-garde abstract painter Agnes Pelton once wrote of her canvases depicting shimmering orbs. She aimed to represent “perfect consciousness,” she noted in one of her voluminous journals, and hoped her artworks would reveal their meanings to viewers with “receptivity to color.”1 Partly because she left so much room for interpretation, a major traveling retrospective, Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist, has drawn crowds in the last year.

Her notes reveal little “about the specific content” of her subject matter, says Gilbert Vicario, the chief curator at the Phoenix Art Museum, where the Pelton show debuted last March with forty-five paintings. As the exhibition has made its way across the country—it is spending this spring at the Whitney Museum of American Art and then heads to the Palm Springs Art Museum—more artworks have been added and more archival fodder for further sleuthing has come to light. The breaking news has only increased the allure of the German-born, Brooklyn-raised artist, whose newfound fame comes as part of a trend in burgeoning scholarship on a range of early women abstractionists. Says Vicario: “People like to be part of the journey of discovery.”

The exhibition’s compositions of cosmic rays and parabolic horizons represent only a fraction of Pelton’s output. To make money, she relied on realistic landscapes, still lifes, and portraits of wealthy patrons. She had to be resourceful, disciplined, and somewhat pragmatic, ever since her traumatic childhood in Brooklyn.

Pelton was the only child of Europe-roaming expats; she was born in Stuttgart to the Brooklyn-born pianist Florence Tilton Pelton (1858–1920) and William Halsey Pelton (1856–1891), a Louisiana sugar refinery heir overly fond of morphine. The Peltons roamed western Europe during Agnes’s early years, but by 1888 had settled in Brooklyn. Her parents were constantly worried about the child’s health. Among her ailments over the years were backaches, bronchitis, melancholy, and “neurasthenia.” The family lived with Florence’s reclusive divorced mother, Elizabeth, whose 1860s affair with the Congregationalist preacher Henry Ward Beecher had been exposed in the press. Moralists blamed and shunned her, despite Beecher’s alleged record of sexual predation (not to mention Elizabeth’s husband Theodore’s own alleged infidelities). Florence, who had glimpsed the lovers around the house, was dragged into years-long salacious coverage and left emotionally scarred. “It cramped her whole life,” Agnes told a friend in 1934. Soon after William fatally overdosed at a family farmstead in Louisiana, Florence set up a successful music school in their Brooklyn home, while Agnes found solace in sketching and painting.

At age fourteen, Pelton enrolled in art classes at Pratt Institute, studying with the influential artist and educator Arthur Wesley Dow. In the early 1900s she spent time in Connecticut, painting scenery with William L. Lathrop in Old Lyme and at a farm that she bought near the town of Killingworth. By the 1910s she had participated in one-woman exhibitions in New York, and the 1913 Armory Show organizers borrowed two of her works, including Vine Wood, which depicts a Connecticut glade looming over a woman sheathed in silky pleats. Critics lauded her moody effects; Brooklyn Life, for instance, noted that her works were “complex, resisting definite analysis” and conveyed “a delightful sense of the fantastic.”2

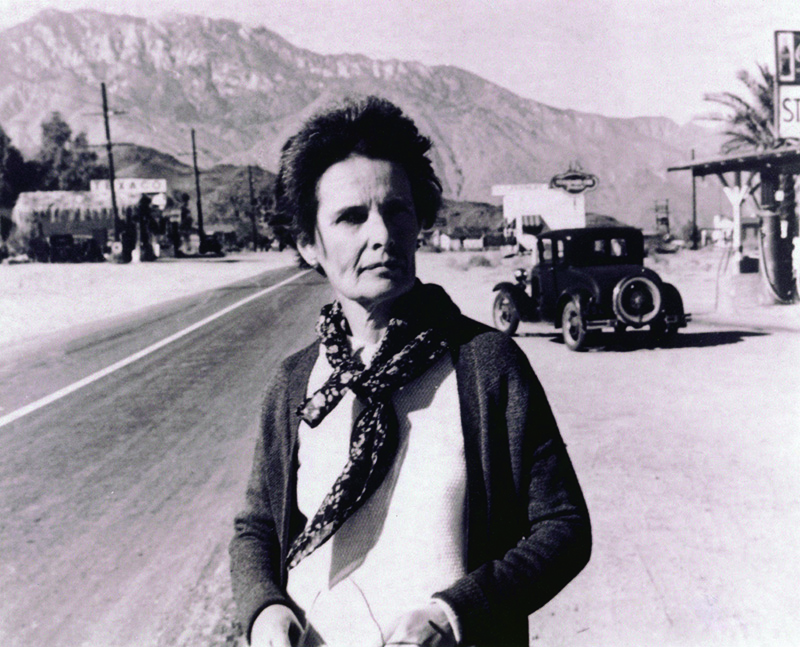

With earnings from artwork sales plus some family handouts, Agnes traveled around Italy, Greece, the Middle East, and Hawaii. She spent months in artists’ colonies at Ogunquit, Maine, and Taos, New Mexico. She befriended art-world celebrities, including the painter Walt Kuhn and the patron Mabel Dodge. But she was shy and self-deprecating, preferring quiet seclusion. In the 1920s she lived in a windmill on eastern Long Island. In the 1930s she resettled in a modest home near Palm Springs. She practiced meditation and recorded her dreams along with lengthy quotes from literary, religious, and philosophical esoterica. She immersed herself over the years in Theosophy, Agni Yoga, Carl Jung’s writings, astrology, and New Thought, a theological movement that emphasized female empowerment and “identified the Holy Spirit as a woman,” the historian Erika Doss writes in the sumptuous exhibition catalogue.

Pelton attracted no major champions among dealers, curators, or collectors. And she apparently had no significant other. The marital woes of her mother and grandmother may have made the prospect of a husband particularly unappealing. “If anyone would know the toxicity of patriarchy, it would be Agnes,” says Susan L. Aberth, a Bard professor who also contributed to the catalogue.

Friends preserved her papers after her death, including sketchbooks and scrapbooks (now in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art). Another trove of images turned up in the summer of 2019 when Nyna Dolby, a floral designer in California and a Pelton cousin (Florence’s brother Carroll Tilton was her great-grandfather), found her late mother’s box of color slides from the 1960s. They show Pelton artworks previously unknown to scholars, and a hunt is on for those canvases, Dolby reports. She has inherited Pelton paintings of a thick-trunked, droopy tree on the Killingworth farm, and of the artist’s mountain cabin near Palm Springs. Dolby is connecting with other descendants, seeking artworks, documents, and anecdotes, and gearing up to write a book about her findings. This spring, she plans to visit the Killingworth property, which Pelton called Wild Farm. As the artist at last receives “the due she deserved,” Dolby says, the reaction among first-time viewers of the luminous canvases is often along the lines of, “Who is this? I don’t know this person, but I need to.”

Dolby has shared information with other aficionados, including contributors to the online publication California Desert Art, which often covers the subject now known as Peltonia. Last fall the website published Ann Japenga’s travelogue of a visit to the Killingworth farm. Among the tantalizing hints of the artist’s presence there are the initials “D. T.” inscribed a century ago on a barn timber, possibly by Pelton’s cousin and sometime model, Dorothy Tilton. The property’s current owner, who has found Pelton’s signed deed, asked Japenga to give only his first name, “to discourage Instagrammers from popping in,” she writes.

The Phoenix exhibition checklist has been updated for its travels with a rediscovery, First Spring Garland, a 1926 canvas that a collector purchased in 1995. Its swoops and triangles suggest an angel dangling blossoms over tan and purplish dunes. Vicario says that discussions are in progress about finding a European venue for the traveling show, perhaps near the Peltons’ Stuttgart haunts.

More studies of Peltonia are underway. Doss says she is finishing a book, Spiritual Moderns: Twentieth Century American Artists and Religion, that “centers on Pelton’s religious interests and intentions, and how she drew on them in her Abstractions.” The Pelton Papers, a fictional memoir by the writer Mari Coates (whose ancestors knew the Peltons in Brooklyn), is due this spring from She Writes Press. Drawing from Pelton’s writings, Coates imagines the artist on her deathbed, sorting through memories from toddlerhood through the last finishing touches of orbs on canvas.

Among the other artists of Pelton’s approximate era and ilk now returning to the fore are Hilma af Klint, Emma Kunz, Mary Sully, Leonora Carrington, Juanita Guccione, Sylvia Fein, and Marjorie Cameron. New books are also appearing about historical figures who worked in mystical abstract modes, such as the medieval abbess Hildegard von Bingen and the nineteenth-century Briton Georgiana Houghton. Aberth reports that her Bard classes are crowded with students eager to hear avant-garde women artists’ stories.

The wave of fresh eyes and new angles, Aberth predicts, “is just the beginning.”

Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from March 13 to June 28. It will be seen at the Palm Springs Art Museum from August 1 to November 29.

1 Except as noted, quotations and biographical details in this article come from the exhibition catalogue, Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist, ed. Gilbert Vicario (Munich: Hirmer, 2019); and from Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts, and the American West, ed. Christopher M. Scheer, Sarah Victoria Turner, James G. Mansell (Lopen, UK: Fulgur Press/Logan, UT: Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, 2019). 2 “An Art Exhibit at Ardsley House,” Brooklyn Life, March 29, 1913, p. 20.

Eve M. Kahn’s latest book is Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857–1907 (Wesleyan University Press, 2019). An excerpt appeared in the November/December 2019 issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES.