How did immigrants transform American fine and decorative arts? This question has been interesting to ponder over the past year of pandemic life, especially as our nation grapples with its long history of racial injustice and continues to debate its policies on immigration. The New-York Historical Society’s forthcoming exhibition and catalogue, The Art of Winold Reiss: An Immigrant Modernist, will provide one vivid answer to this question. The German-born artist and designer is known today for his striking portraits of leading figures in Harlem arts and society, and is often grouped with the early twentieth-century’s most influential designers— Norman Bel Geddes, Paul T. Frankl, Josef Hoffmann, and Joseph Urban. Yet, he is less frequently regarded as a design pioneer instrumental in bringing modernism to the United States. Assembling highlights from the Reiss Archives and his immense body of surviving work, the groundbreaking exhibition will demonstrate how one immigrant modernist exerted a lasting impact on twentieth-century American portraiture, interiors, graphic designs, furniture, and more.

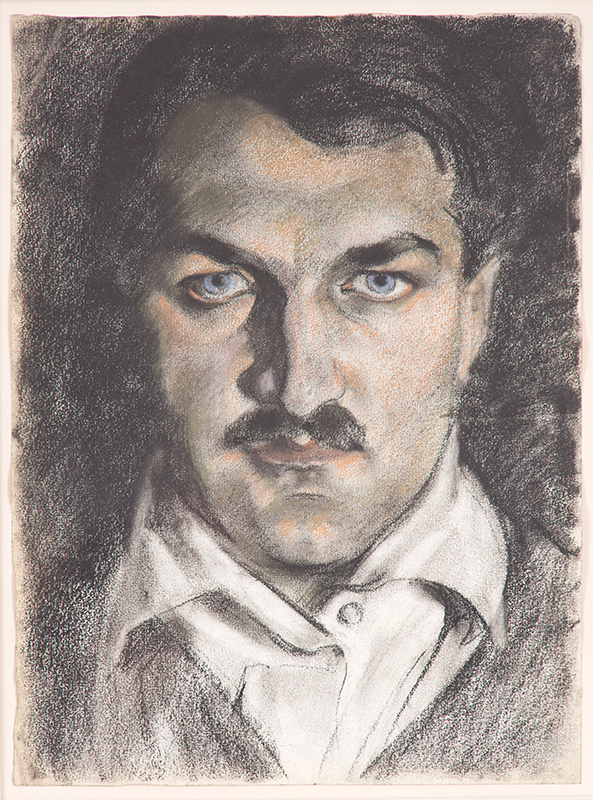

Born in Karlsruhe, Germany, Fritz Wilhelm Winold Reiss arrived in the United States on October 29, 1913 (Fig. 2). The son of Fritz Reiss, a genre painter, illustrator, and lithographer, Winold trained in Secession-era Munich at the Munich School of Applied Arts and the Royal Academy of Fine Art under such notables as artist and designer Julius Diez (1870–1954) and Franz Von Stuck (1863−1928), the renowned painter and a leading member of the avant-garde artists of the proto-modern Munich Secession. Munich was still one of Germany’s most influential art centers when Reiss arrived in 1910, and many of its resident artists championed “New Art” and its fresh expressions of form, color, and line. Reiss studied woodworking, furniture making, interior and industrial design, studio painting, perspectival and figure drawing, color theory, and art history, and almost certainly visited the city’s many Jugendstil and Secessionist art and design exhibitions. He married Henriette Lüthy (1889–1992), an artist and designer, in 1912, but traveled to New York alone the next year. She and the couple’s infant son, Tjark, followed five months later. Much of the couple’s correspondence from this time survives, offering candid glimpses into his initial New York experiences.

Reiss settled in New York shortly after the 1913 Armory Show in a city still buzzing about the modern art displayed at the exhibition. In a letter to Henriette, he described American art as “like Germany 60 years ago,” but envisioned modernism as a rich opportunity for artists and manufacturers.1 He quickly established a studio, at 95 Fifth Avenue, and found work with the International Art Service, a branch of the leading Berlin poster printing company, Hollerbaum and Schmidt. The work was fast-paced and challenging. As he informed Henriette, “You can’t imagine how they work here. The brain has to work like a steam machine. . . . What they put on your desk in the morning you have to have done by night. You learn how to be fast and lose the slack Munich ways.”2 During this time, he also secured his first major graphic design commission, illustrating book covers for Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Reiss left the International Art Service after a few months, and founded the Crafts and Art Studio with two fellow immigrants, Jacob Asanger and Alfred Besel. The partnership was short-lived, but during it he began teaching art classes and designing Jugendstil and peasant-style furniture and housewares (Fig. 5).

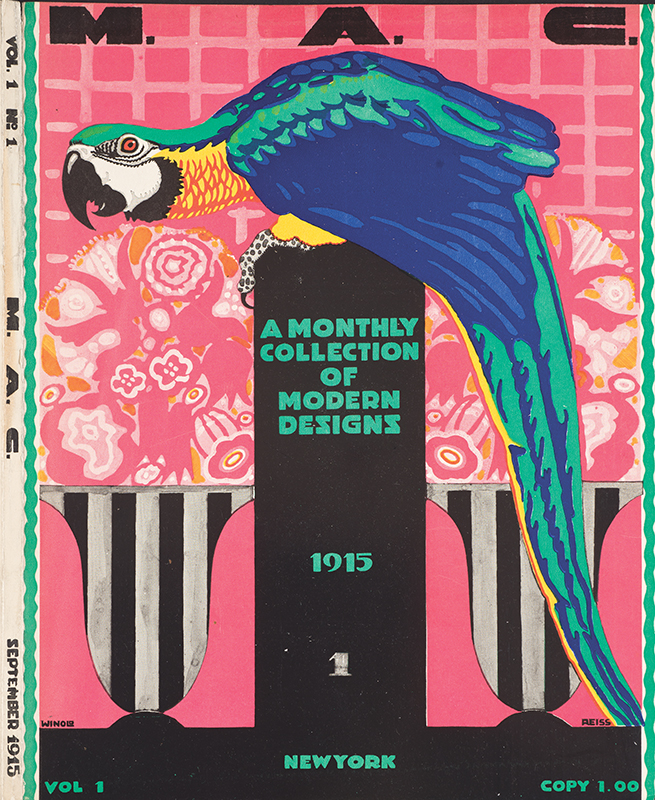

Reiss opened his first art school–proper in 1915, and continued to design posters and graphics. He also started an art and design magazine, M.A.C. (Modern Art Collector), in which he broadcast his faith in modernism as a transformational movement (Fig. 1). Published from 1915 to 1918, M.A.C. demonstrated the commercial potential of modernist forms, lines, and colors in thought-provoking articles, and in vibrant posters, illustrations, advertisements, and interior designs. The magazine also introduced him and other modernists, such as textile designer Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981), to the American public. Reiss hoped M.A.C. would generate excitement about modernism while quelling concerns about its inaccessibility: “A few years ago, a tidal wave of Modernism in Art swept over Europe. . . Like all movements, it first came to notice when it made sufficient noise, and eventually its bold lines and strong colors cried out loud enough to make themselves heard. . . Our object in bringing out these pages . . . is to enable this country to keep in touch with modern artistic European tendencies . . . and thereby encourage the development of the Modern Movement. . . That we hope will prove of value and of interest to the Public, to the Individual and the Trade.”3 In articles such as “The Modern German Poster,” Reiss recommended that graphics should “strike your eye and remain in your brain,”4 especially from a fast-moving car or train. Stylish advertising posters were cornerstones of late nineteenth-century German marketing campaigns, characterized by central images depicted in flat fields of three or four colors, and accented with patterned backgrounds, decorative borders, and minimal text. As Reiss noted, “there isn’t a good artist in Germany who wouldn’t design a poster.”

Reiss’s earliest book jackets, magazine covers, and advertisements embraced this aesthetic. His first book jacket for Scribner’s—an English translation of Knut Hamsun’s 1893 novel Shallow Soil—designed in 1913–1914, presented five patrons seated in a café beneath a hand-painted title emblazoned like a marquee. His second book jacket, a “wraparound” cover (one of the first of its kind) for Frederick Palmer’s The Last Shot (1914), captured the novel’s ominous plot with a panorama of armed soldiers, silhouetted in black, marching beneath a bright orange sky.

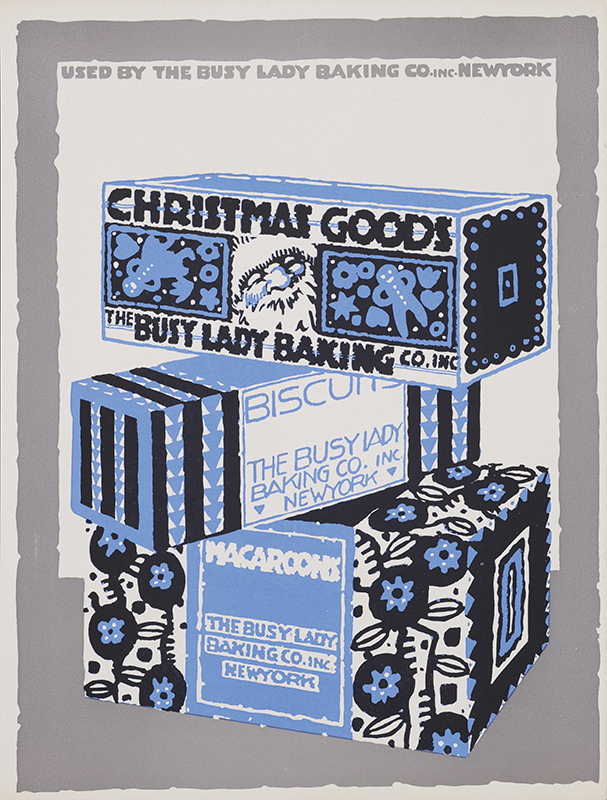

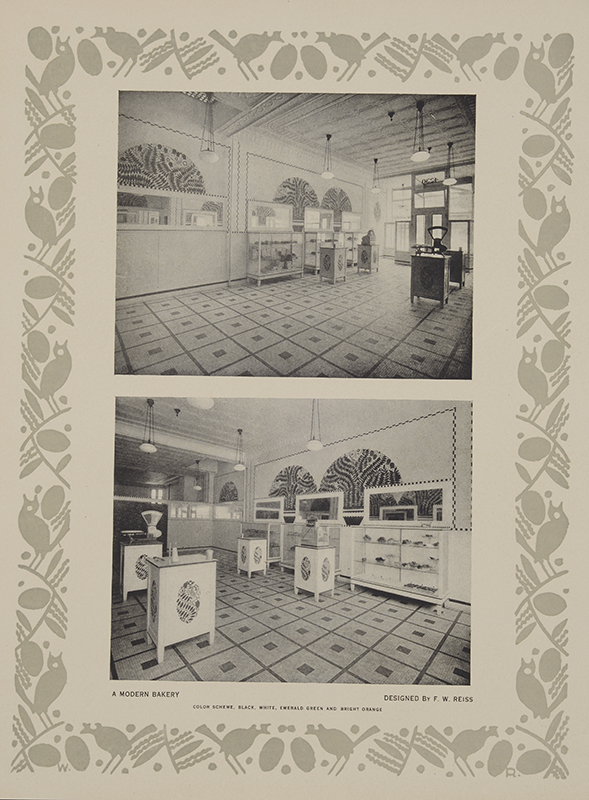

Reiss’s first comprehensive interior and graphic identity project, for the Busy Lady Bakery shops at 3620 and 4230 Broadway, showcased his evolving design vocabulary. He transformed the interiors into hygienic grids of checkered floors and walls accented with green lunettes. Conversely, the spirited packaging for Busy Lady’s (Fig. 6) baked goods evoked the delicious contents: boxes for cookies, biscuits, or macaroons adorned with jovial Santas, trays of blue gingerbread men, lively zigzag borders, and dancing flowers festooned with playful black lettering (Fig. 4). Other motifs—tumbling scrolls, swelled garlands, silhouetted flowers and foliage bursting from flowerpots, cubist skyscrapers, sawtooth cityscapes, and his signature emphatic, or falling, S—appeared in promotions for his own nascent studio and art school, too.

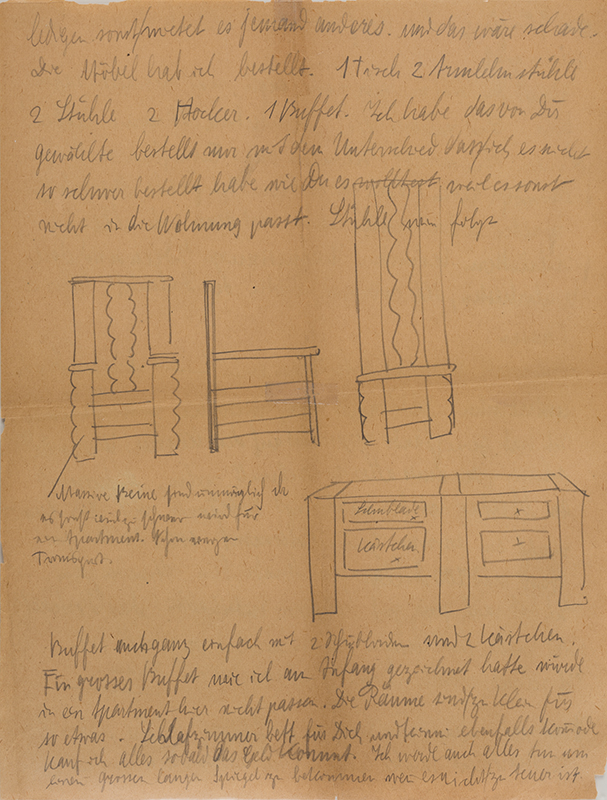

Reiss’s furniture designs of the period typically had simple, rectilinear forms, and used dark woods, or had painted decorations in stylized plant and animal motifs. Members of the Munich Secession and Wiener Werkstätte championed folk-inspired goods, believing that vernacular craftsmanship and ornament inspired fresh interpretations in the applied arts. A sideboard painted cobalt blue, trimmed with bold scalloped edges and shaped iron hardware, and with a vermilion top and drawer interiors, evoked the vernacular Black Forest forms he saw as a youth. The Werkstätte style is also visible in a dining set he designed for his family. Illustrated in a letter to Henriette in 1914, its ample, right-angled arm- and side chairs with tall, confidently scalloped back splats and legs recall Richard Riemerschmid’s functionalist furniture and Josef Hoffmann’s Sitzmachine and Fledermaus chairs.5 Reiss’s chairs, made of deeply grained chestnut, still survive (Figs. 7, 8).

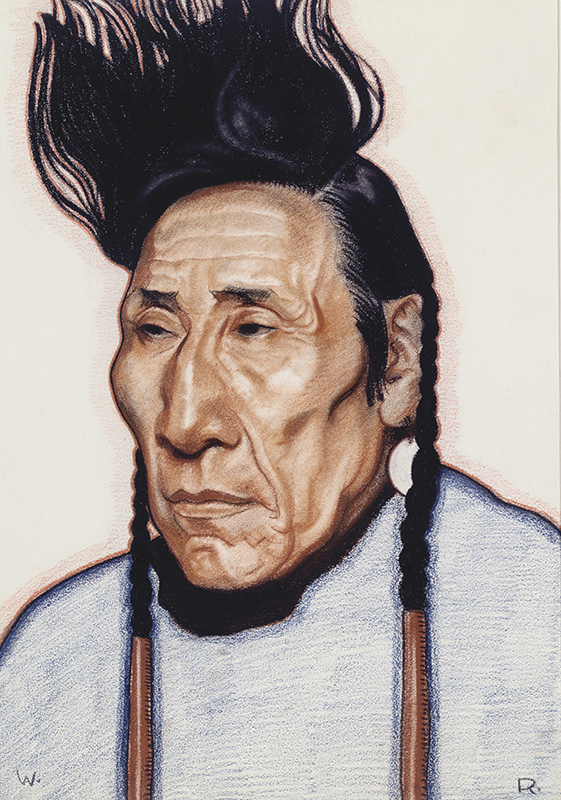

Captivated, like many of his peers, by stories of Native American life, Reiss embarked on his first trip to the US west to visit the Blackfeet in 1920, later writing: “I made my first trip to the Blackfeet Reservation, and was so fascinated with the Indians which I found there and by their majestic country that I have ever since spent my summers with them.”6 Reiss’s fascination with the Natives of the western United States began during his childhood, and when he arrived in 1913 he assumed that they lived in and near New York City.7 During the 1890s Germans had engaged in cultural reflection, particularly in response to the industrialization of their cities, and many sought folkloric representations of the past, which spurred interest in the American West. European tours of “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” extravaganza (including a stop in Karlsruhe in 1891) and the popular frontier novels of James Fenimore Cooper and Karl May fed this fascination.

Reiss felt an artistic kinship with Native Americans but was also mindful of their traumatic history, noting, “I regret that everything was taken away from them and nothing was left.”8 He spent two weeks at the Blackfeet Reservation in Browning, Montana, and produced at least thirty-six portraits of tribal members (Fig. 11). Back in New York, his friend Ernst Hanfstaengl exhibited nearly all of the portraits in his gallery. Before the end of that year, Reiss spent two months in Mexico, drawing portraits of Zapata revolutionaries that later appeared in a special issue of Survey Graphic magazine featuring an article by novelist Katherine Anne Porter.

Survey Graphic editor Paul Kellogg and cultural critic Alain Locke (1885–1954) commissioned Reiss to undertake a visual exploration of Harlem for a special March 1925 issue, “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro.” Reiss saw the neighborhood’s urban, African American population as epitomizing the complexities of the modern American character. This viewpoint is palpable in his stirring portraits of “Harlem types.” As Jeffrey C. Stewart notes in his catalogue essay: “By bringing the image of the New Negro into American Modernism, Reiss established that Black people were not bystanders of modernity but actually social actors in its construction in places such as New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh—but especially in Harlem, where he had a unique opportunity to observe what was being created there and to translate that observation into some of the most powerful portraits of Black people made on this continent.”9

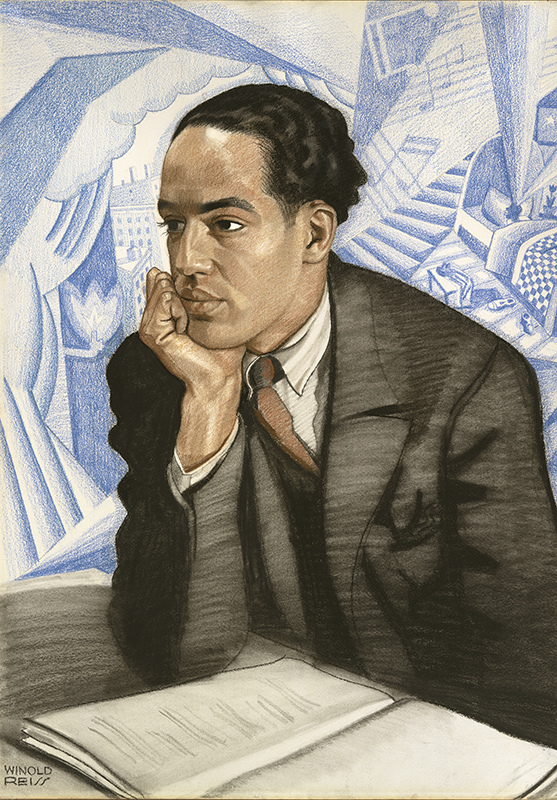

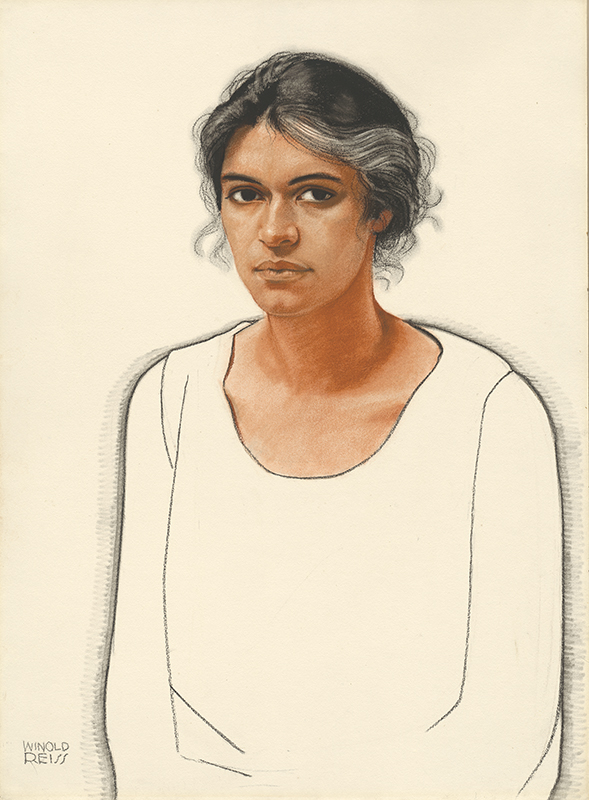

Locke connected him with “Black leaders, artists, and social reformers,” and Reiss spent considerable time in Harlem meeting and drawing its many residents. These intimate portraits demonstrated Locke’s vision of Harlem as a “crucible” for “the African, the West Indian, the Negro American . . . the Negro of the North and the Negro of the South . . . the man from the town and village . . . the student, the artist,” and he included many of them in The New Negro: An Interpretation, an anthology of literature and art inspired by the special issue, published in 1925.10 The portraits depict Black teachers, librarians, physicians, nurses, mothers, fathers, children, and such luminaries as Locke, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes (Fig. 9), Zora Neale Hurston (Fig. 10), and women’s rights leader Elise Johnson McDougald. Surely, his immigrant experience aided Reiss in drawing out his sitters’ humanity and power.

Reiss designed dozens of celebrated restaurants, clubs, hotels, and shops in and outside of New York. His restaurant interiors were among the first to feature lively colors, multi-tiered layouts, synthetic fabrics and other new materials, and state-of-the-art ventilation and lighting systems. The Restaurant Crillon (1919), widely considered the city’s first modern restaurant, featured distinctly colored and themed Batik, Prismatic, and Winter Garden Rooms. The theatrical interior of the Alamac Hotel’s Medieval Grille (1923), inspired by medieval tapestries, costumes, and architecture, incorporated life-size metal panels overlooking the booths.11 Made using his state-of-the-art chemical and heat treatment, known as the “Winold Reiss Metal Process,” the fused repousséd iron, copper, brass, steel, and aluminum panels were sculptural works of art (Fig. 12).12

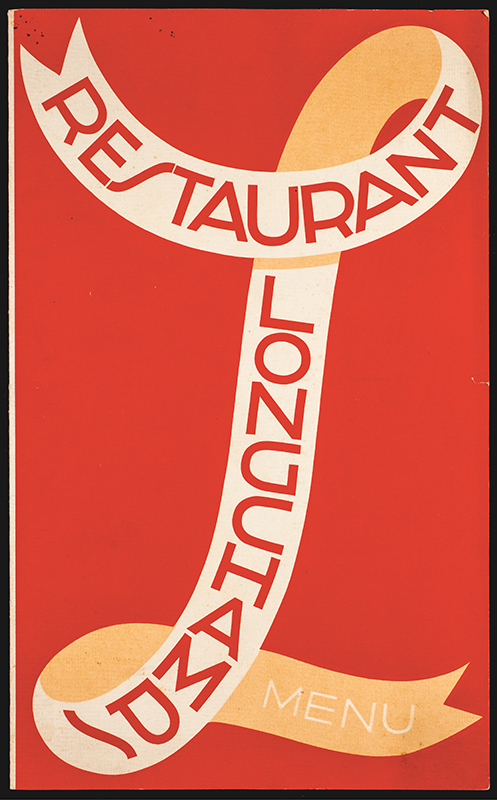

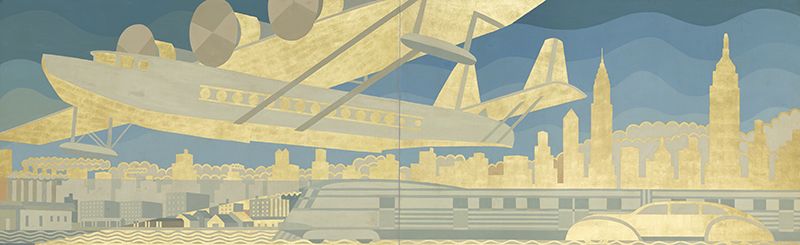

Reiss integrated his studio art into the interiors of ten of the city’s Longchamps restaurants. The “Indian”-themed Longchamps on Madison Avenue at East Fifty-Ninth Street incorporated his Blackfeet portraits, while the Times Square outpost on West Forty-First Street presented his sleek City of the Future mural (Fig. 13). In contrast, Longchamps’s cohesive graphics, including its menus, were uniformly emblazoned with the chain’s large, italic L ornamented with vermilion lettering and Reiss’s falling S (Fig. 3).

Reiss renovated a twenty-one-room Fifth Avenue triplex for Theodore Weicker (1862–1940), chairman of the Squibb pharmaceutical corporation, in 1926. His redesign of the foyer, library, living and dining rooms, bedrooms, and roof garden interwove symmetry, color, and new materials into an artistic, livable space.13 Surviving studies of the apartment’s doors, gates, grilles, balustrades, radiator covers, and consoles illustrate that his extensive metalwork harmonized the public and private rooms (Figs. 15).

The furniture Reiss designed for his interiors combined inventive color combinations with unexpected accents. This is particularly evident in studies of the public rooms of the Shellball Apartments (1928) in Kew Gardens, Queens. For the building’s lounge, his roomy purple, barrel-shaped club chairs with silver piping, an ample matching “couch” with attached side tables, and curvilinear side chairs upholstered in seafoam green offset yellow and silver walls and ceiling (Fig. 17). The furniture studies also illustrate reinterpretations of these forms for broader audiences. Reiss re-created the Shellball couch with removable end tables for apartment dwellers in cobalt and vermilion (Fig. 16). Other furniture studies show blocky silver cabinets that doubled as desks and weighty chests enlivened with striped yellow and orange surfaces. For the new electronic devices of the day, he created sleek, angular, and broad radio cabinets, including a tall turquoise model topped with a black pagoda, balanced on straight legs.

Reiss copyrighted and patented designs for metalwork, textiles, and lighting. Most visible, perhaps, was the decorative lighting system for the three-story Grand “Colorama” Ballroom at the posh Hotel St. George in Brooklyn Heights.14 Acclaimed as “a step in the direction of the use of light as fine art,” the system projected thousands of color and pattern combinations.15

New materials manufacturers were among the first to collaborate with modern architects and designers. 16 As Reiss forecast in M.A.C., such partnerships could educate consumers and boost sales. Fascinated by the new metals, plastics, and synthetics of the day, Reiss partnered with the International Nickel Company to design lamps, screens, and grilles made of Monel, a nickel-copper alloy; with the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) and the General Fireproofing Company for aluminum chairs; and with DuPont for textiles.

The Reiss Archives includes hundreds of sketches, presentation drawings, notes, and business records that attest to his virtuosity, dedication as a teacher, and faith in modernism. Quantifying the extent of his impact on American design is challenging, as surviving artwork, studies, and records do not represent the full body of his work. Restaurants dominated his interior projects, but Reiss also supplemented these commissions with undocumented furniture, metalwork, and lighting design assignments. His domestic interiors, in particular, remain largely unknown. Less publicized private commissions, including interiors for the Southampton home of Merrill Lynch co-founder Charles E. Merrill, come to light only in vague newspaper mentions that imply a holistic approach to the space, furniture, and wall, floor, and window coverings. Reiss may be the greatest designer you’ve never heard of, until now, and the upcoming exhibition and catalogue of his art, graphics, and interior designs, furniture, and metalwork will reveal the impact of one of the United States’ most influential artists and designers of the twentieth century.

The Art of Winold Reiss: An Immigrant Modernist is now scheduled to open at the New-York Historical Society in July 2022. The accompanying catalogue, edited by Marilyn Satin Kushner, with essays by Kushner, C. Ford Peatross, Jeffrey C. Stewart, and Debra Schmidt Bach, published by the New-York Historical Society in association with D. Giles, will be available this June.

1 Winold Reiss to Henriette Reiss, November 19, 1913, Reiss Archives, private collection, Hudson, New York. 2 Winold Reiss to Henriette Reiss, January 14, 1914, ibid. 3 “Foreword,” M.A.C.: A Monthly Collection of Modern Designs, vol. 1, no. 1 (September 1915), p. 8. 4 F. Winold Reiss, “The Modern German Poster,” ibid., p. 12. 5 Winold Reiss to Henriette Reiss, November 18, 1914, Reiss Archives. 6 Winold Reiss, “Notes on the Work of Winold Reiss Studios,” 1938–1941, Reiss Archives. 7 W. Tjark Reiss, “My Father Winold Reiss—Recollections by Tjark Reiss,” Queen City Heritage, vol. 51, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 1993), p. 68. 8 Winold Reiss to Henriette Reiss, November 23, 1913, Reiss Archives. 9 Jeffrey C. Stewart, “Winold Reiss’s American Studies,” in The Art of Winold Reiss: An Immigrant Modernist, ed. Marilyn Satin Kushner (New York: New-York Historical Society/London: D. Giles, 2021), p. 48. 10 Ibid., pp. 51, 55. 11 Eugene Clute, “Today’s Craftsmanship in Combining Metals,” Architecture Magazine, vol. 70 (October 1934), pp. 203–208. The Medieval Grille room panels were among the first metal panels to be integrated as decorative elements in an interior design, and may have influenced metalwork created for Rockefeller Center in 1932. 12 “Winold Reiss Shows Metal Process Panels—Garden Club Exhibition,” Sun and Globe, November 24, 1923, p. 3. 13 Theodore Weicker to Winold Reiss, February 26, 1926, Reiss Archives. 14 See Design Patent No. 2,029,543 (awarded February 4, 1936), “Method of and Means for Creating and Displaying Decorative Effects with Light,” United States Patent and Trademark Office. 15 “St. George Addition Now Formally Open, Brooklyn Hostelry Now Largest in Metropolis, with Total of 2,632 Guest Rooms and Ample Banquet Facilities—Colorama Ballroom a Striking Feature,” National Hotel Review, vol. 25, no. 43 (March 22, 1930), pp. 11–13; and “An Experiment in Light,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 2, 1930, p. 32 16 Jeffrey L. Meikle, American Plastic: A Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), pp. 100–112; and “Donald Deskey: Innovative Designer, Dies at 94,” New York Times, April 30, 1989.

DEBRA SCHMIDT BACH is the curator of decorative arts at the New-York Historical Society. She has curated and collaborated on an array of popular and social history exhibitions at the historical society, including Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere; Life Cut Short: Hamilton’s Hair and the Art of Mourning Jewelry; and Celebrating Bill Cunningham. My deepest gratitude to C. Ford Peatross for sharing his article “Winold Reiss: A Pioneer of Modern American Design,” Queen City Heritage, Summer/Fall 1993, pp. 38–57, as well as much of his unpublished research on Reiss.