Part I: Founding editor Homer Eaton Keyes

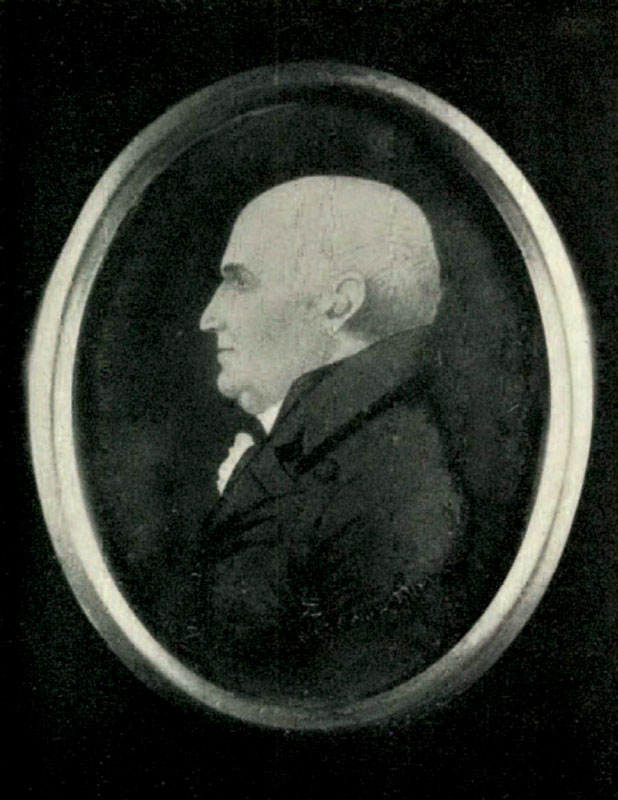

“It was Mr. Keyes,” said Alice Winchester, “who opened up the wonderful world of antiques to me. . . . I had everything to learn, and I was most fortunate in having a boss who was a great teacher.” 1 Alice worked for Homer Eaton Keyes (1875–1938), founding editor of ANTIQUES, first as his secretary and then as an associate editor, from 1930 until his unexpected death in 1938, when he was only sixty-two years old.

She succeeded Keyes as editor in early 1939, remaining in the editor’s chair until her retirement in July 1972. She intended to write an article about Keyes after she retired, but somehow the idea was always pushed aside by an invitation to lecture, or to curate an exhibition, or, as time went by, the need to care for her two older sisters. So, sadly, the article never took shape.

If she had written about Keyes, Alice would have provided details about his professional, personal, and collecting life that are now irretrievable, for he left no correspondence or other papers. This article is therefore based largely on the recollections Alice conveyed to me in casual conversations and interviews, on talks she gave to various groups, on papers in my possession and at Dartmouth College, and on her and Keyes’s writings in ANTIQUES.

During the years I worked for her in the 1960s and early 1970s, Alice often talked about Keyes (pronounced “kize”—rhymes with size). She invariably referred to him as “Mr. Keyes,” and that is how I have continued to think of him. In my mind he was—and is—an awe-inspiring figure, although when I read his chatty commentary in the “Editor’s Attic,” as he called both his actual office and the magazine pages containing his editorial comments, he comes across as friendly, humorous, and not at all godlike. 2 In fact, in some of his reflections—what he called his “ramblings”—his language becomes positively florid, making him seem even more human, and occasionally sentimental and old fashioned.

Keyes was neither of those things when it came to setting the standards for his magazine. Articles were substantive, well written, and never exemplified what he called the “quest of the quaint” school. Mabel Munson Swan, who began contributing articles on Boston and Salem furniture in 1926, wrote that Keyes “was never too busy to be consulted, never too hurried to advise. If he asked us to do any research, we knew that we must dig to the bottom, for he was as impatient of superficiality as he was of inaccuracy.” Dr. Irving P. Lyon, author of a series of articles on the oak furniture of Ipswich, Massachusetts, published in 1937 and ‘38, wrote, “The policy of Mr. Keyes—careful editing and concentration on original research—lifted ANTIQUES far above its ephemeral competitors, and will doubtless keep it a fixture in its field.” And the august Fiske Kimball, architect, architectural historian, and director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1925 to 1955 , proclaimed that “The Magazine ANTIQUES . . . has done a great service by constantly printing articles of true scholarly importance, vastly increasing the exact knowledge of American craftsmanship.”3

Born in 1875, Keyes grew up in a brownstone in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. His father, Emerson Willard Keyes, was an educator and an attorney whose book Special Report on Savings Banks of 1868 became a standard reference throughout the United States. His half-brother, Willard Emerson Keyes, wrote several articles for ANTIQUES in the 1920s and 1930s, usually on offbeat subjects such as Yankee Clipper cards, John Barleycorn, and Cleopatra’s Barge. Another brother, Conrad, was a prominent Brooklyn attorney, and their sister, Rowena, was an eminent teacher, administrator, and writer on education.4

Keyes’s qualifications for the job as editor of a new magazine devoted to antiques developed gradually. In his senior year at Brooklyn Boys’ High School he was editor and an illustrator of the monthly Recorder, which “leaped to the front rank of scholastic monthlies” under his leadership.5 After high school and a year of studying art and design at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, Homer Keyes entered Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, graduating in 1900 magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa.

Homer Eaton Keyes was “perhaps our most talented and versatile member,” wrote a Dartmouth classmate.6 Besides excelling academically, he engaged in a variety of outside activities—from the Glee and Mandolin Clubs to the Vaudeville and Minstrel Shows to managing Carnival Week. His senior year he was editor-in-chief of both the school paper, The Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Literary Monthly. Upon his graduation, Keyes joined the Dartmouth faculty as an instructor in English; in 1906, he helped to establish the fine arts department and was made assistant professor of modern art.

Keyes continued the pattern of combining academic and extracurricular activities in his postgraduate years. During his first decade as a Dartmouth employee, he seems to have served as a one-man design and production department for both the college and the larger Hanover community. Among his many projects were the designs of spaces and furnishings of several college buildings and the design and production of printed materials for important college events. In 1908 he designed ironwork and signs for the Hanover Inn, which was perhaps a factor in a local newspaper’s assertion that Keyes’s greatest contribution to the community was “what he did to make Hanover lovely to the eye.” Much of the “charm of Hanover is traceable to his artistic spirit and his efforts to make Hanover beautiful,” the article declared.7

Keyes married Caroline Gardner Abbott (1876–1938) in New York City on April 2, 1903. They took a two-year honeymoon trip to Europe, where their only child, Katherine, was born and where Keyes attended lectures at the University of Munich.8 In 1906, after the family returned to Hanover, Keyes designed and built a spacious arts and crafts style house with swooping roofs and low shed dormers. Situated on land adjacent to the college, Keyes’s house, said a friend, was, “during the years of his long Hanover residence, the centre of a delightful and stimulating hospitality.”9

We can only guess at the decoration and furnishing of the house, but it must have contained antiques. Alice Winchester recalled Keyes telling her about going antiquing in and around Hanover with a group of local collectors. Among them was Alice Van Leer Carrick, wife of Dartmouth professor Prescott Orde Skinner. Neither Keyes nor Carrick wrote specifically about this collecting group, although Carrick’s many articles and books about her antiquing adventures made frequent reference to one friend or another, “L—–,” or “H—–,” as she referred to them. (I was hopeful that “H” stood for Homer, but was disappointed to discover, as I read on, that “H” was a woman.) That Keyes frequented antiques shops and auctions is clear from his coverage of them in ANTIQUES. Many of his friends were collectors and dealers; he visited them at their homes and shops and encouraged a number of them to write about their specialties for the magazine.

Alice Van Leer Carrick (1875–1961) was a remarkable woman who combined the skills of childrearing and housekeeping with a passion for hunting up antiques that she then researched and wrote about.10 She began to collect, she said, because modern furnishings seemed inappropriate for her small eighteenth-century house, Webster Cottage, where famed lawyer and statesman Daniel Webster had lived during his sophomore year.

“Through storm and sunshine, along dusty roads and up unspeakably muddy lanes, from sunrise until there is hardly a light left twinkling in the lonely farmhouses, we have followed and found our treasures,” Carrick wrote of seeking antiques.11 Such excursions were not the only way to find antiques, however. Even in a small college town like Hanover, Carrick said, “there are frequently sales, removals, people willing to ‘part with’ some heirloom.”12 There were also sales of students’ furnishings, some of which were antique, and country auctions—“a country auction is a neighborhood entertainment: everybody goes,” she wrote. And in cities, particularly on the East Coast, there were “small, inexpensive old-furniture shops, and places where second-hand goods are sold, and little auction rooms—even big auction rooms on a rainy day or at an off season,” in which she found antique bargains.13 Besides these sources, Carrick advised developing a relationship with a local junkman: “For he travels over the country, not by avocation as you do, but by the law of livelihood’s stern necessity; he covers ten miles to your one; and he will go to places you would never dream of discovering. Of course, until he is trained, he will bring in fearful rubbish.”14

But with patient coaching, the junkman will improve over time, said Carrick, and will bring the persevering collector real treasures.

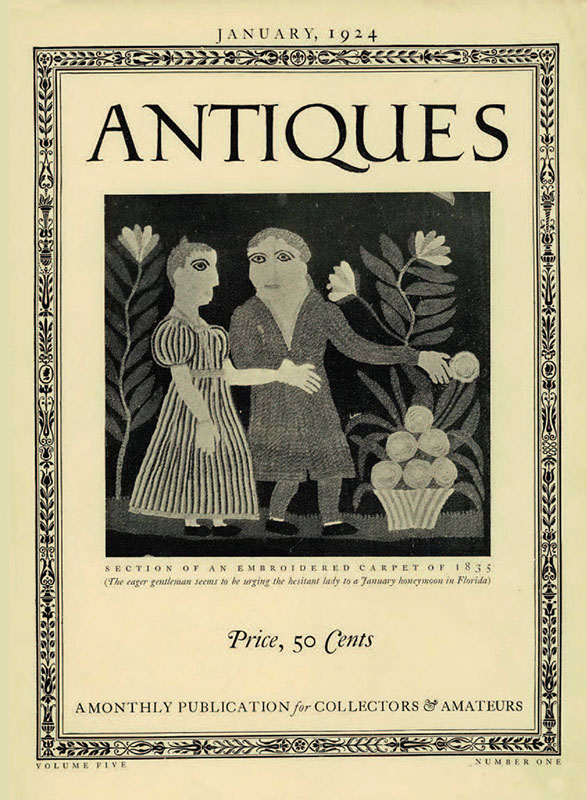

The illustrations in her books and articles tell us that Carrick liked relatively simple pieces. That Keyes shared many of Carrick’s tastes we know, for he, too, was attracted to early furniture, glass, ceramics, and textiles of the kind she described and pictured—the most famous piece he owned was the Caswell carpet, now an icon of American folk art, which was embroidered by a Vermont woman in 1835.15 But the main thing Keyes and Carrick may have had in common was their enthusiasm for the hunt, the capture, and—this is much rarer among collectors—their passion for studying, researching, and writing about their finds. Both conveyed information informally, from a personal yet thoughtful and factual point of view. Their presentations, though quite different, engaged their readers as no dry recitation of facts would have done.

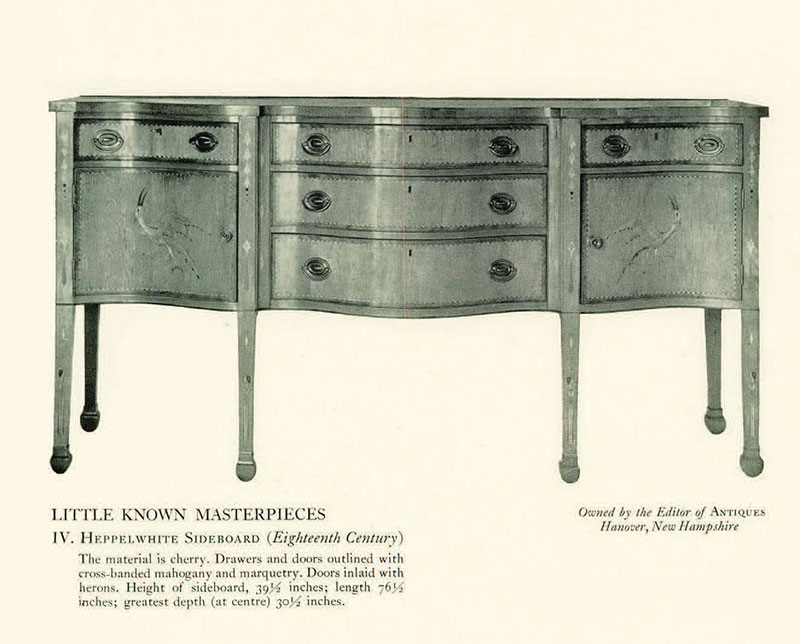

The major difference between Keyes and Carrick was that Carrick was eager to share stories about her finds and her collecting adventures. She encouraged her readers to collect, showing them how, and educating them about many individual categories of antiques. Keyes, with only one exception that I know of, shared his thoughts about objects, dealers, auctions, and antiques shows but not about how he acquired specific pieces. He focused less on the collecting experience than on information about collectible objects.16 Despite any minor differences they might have, however, the value Keyes placed on Carrick’s knowledge and judgment is apparent in his appointing her ANTIQUES’ Consulting Editor, a position she held from January 1922 through January 1942.

In 1913, after his return to Dartmouth from a two-year leave to study at Princeton for a Master of Arts degree, Keyes was, surprisingly, named business director of the college “to Relieve Dartmouth President of Fiscal Cares.”17 He was the first to hold that position and he made a spectacular success of it. Dartmouth had fallen from the top rank of schools such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton after the Civil War, partly because of its remote location, but also because Dartmouth College buildings lacked running water and were heated only by stoves—and winters in Hanover were long and very cold. As business director, Keyes created a profitable water company and built fourteen up-to-date student dormitories, which “paid several percent upon the investment.” In addition, under Keyes’s management the assets of the college tripled and its income doubled.18

After eight years as business director, Homer Keyes made another surprising career switch. His college classmate Frederick E. Atwood (1875–1948) was inspired by his cousin Sidney M. Mills (1877–1961) to start a magazine devoted solely to antiques, and Keyes was invited to become its editor. Sidney Mills was a longtime collector who was, as Keyes wrote, “a student and connoisseur of early American furniture.”19 Another aspect of Mills’s work was described by Atwood’s wife, Marion: “Sid and his wife . . . bought interiors of fine old houses, removed the paint and refinished the mantels, paneling, doorways, and other woodwork, and sold to buyers who were restoring old houses. Ethel did some other interior decorating. They both had first-class knowledge of antiques and excellent taste.” 20 Henry Francis du Pont and the Henry Cabot Lodge family were Mills customers, said Marion, as was the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for which Mills removed and shipped the interior elements of the American Wing’s Hart Room from Ipswich, Massachusetts.21 For ANTIQUES, the job of Mills and his wife, Ethel, was to find advertisers.

Atwood headed up the business side of the enterprise. He, too, was a collector—but of stamps. He was in the printing and publishing business, specializing in publications relating to the shoe and leather industries before his association with ANTIQUES. To get the magazine going, Atwood put up the money for furniture, equipment, and other office expenses, which included “Miss Clark’s salary” of $20 per week. ANTIQUES was at the same address as Atwood’s business and he and Keyes worked together very amicably. Keyes said that Atwood possessed “a genius for attending to his own responsibilities and permitting others to look after theirs. . . . To the editor he gave complete freedom of the Attic and an untrammeled hand in shaping editorial policies.” Of his own beginnings at the magazine, Keyes wrote:

“In October of 1921, a small office was opened at 683 Atlantic Avenue in Boston, and the actual work of preparing the first number of ANTIQUES for publication was begun. . . .Those were hard-working days. It was necessary to make the bravest possible showing with the least possible expenditure of money. . . . Furthermore, the search for satisfactory contributions was complicated by the sad discovery that most contemporary American magazine writers engaged in discussing antiques were not investigators, but journalists [who produced] not invariably trustworthy data. The authors of such important books as commanded respect for sound and original scholarship were naturally hesitant to lend their reputations in behalf of an unknown and untried publication. There was nothing for it but to search out and encourage a new group of contributors who really had something worth while to impart. . . . Many who did their first writing for ANTIQUES . . . have subsequently received general recognition as authorities in their chosen fields of study.”22

Keyes’s contribution to the business side was to work without pay for a year. In fact, that first year Mills was the only one of the founders to receive a salary. Happily, the magazine prospered and by the end of its second year was in the black.23

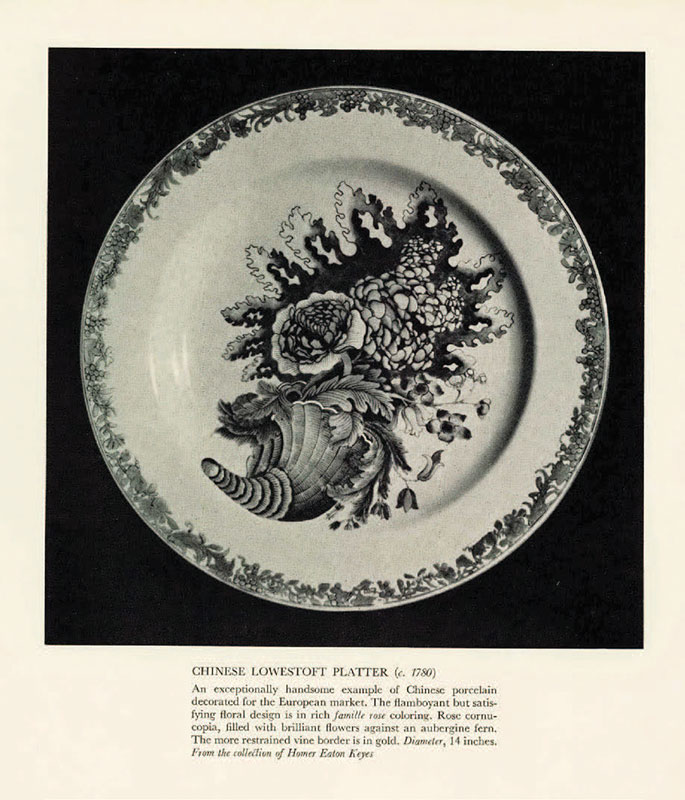

Keyes, like many of his new contributors, became an authority on American antiques. He maintained that he was a generalist, but he was in fact an expert on “Chinese Lowestoft”—what we now call Chinese export porcelain; his lengthy series of articles on these wares was a major contribution to the field. And, as Winchester pointed out in a memorial tribute, his articles for ANTIQUES and other publications attest to his expertise in many additional subjects. These include furniture—he was particularly interested in that of pre-Revolutionary New York and of Duncan Phyfe, and he brought Biedermeier furniture to the attention of American collectors—silver, glass (another of his favorites), pewter, paintings, prints, and textiles among them. His articles in many cases, said Alice, “represent exhaustive analyses.”24

Keyes performed remarkably as ANTIQUES’ founding editor, as he had done as Dartmouth’s business director. In the first issue, he set forth, in “ANTIQUES Speaks for Itself,” the aims and ambitions as well as the limitations of the new publication, decreeing what subjects it would cover and, just as importantly, which it would not. From the beginning he supplied a good deal of the content himself. For that first issue of January1922, he contributed articles on Thomas Sheraton and Boston antiques shops, along with book reviews and notes on exhibitions and auctions. He also wrote, under the pseudonym Bondome, “The Home Market: Random Observations of Interesting Things.” In all subsequent issues, he similarly turned his capable hand to a miscellaneous assortment of tasks—what he called his “infinitely multiplied duties”—which included writing advertising, as well as editorial, copy. He didn’t carry the editorial load entirely alone, however. He wrote that Priscilla Coleman Crane assisted him with research and in many other ways, while Alice Van Leer Carrick advised him on the interests of a wide variety of collectors. Lawrence Spivak, a recent Harvard graduate who eventually created “Meet the Press,” joined the staff to assist Atwood on the business side.

The magazine did so well that in the mid-1920s it received inquiries and offers from several potential buyers. The founders weren’t inclined to sell then, but Fred Atwood suffered a severe illness in the late twenties that affected his ability to concentrate on business. In addition, it was clear by that time that the center of the antiques world was shifting from Boston to New York. In 1929, when an offer came from Asia magazine, a buyer Keyes described as “both strong and sympathetic,” it was accepted. The sale price was $215,000 (over $3 million in today’s dollars), which was divided among ANTIQUES’ shareholders. Besides the three founders, these included Fred’s brother, John Atwood, and Lawrence Spivak, with Keyes and Atwood owning the largest number of shares.

ANTIQUES was now owned by Asia’s founder, Dorothy Whitney Straight Elmhirst. Upon the death of her father, William Collins Whitney, in 1904, Dorothy inherited an enormous fortune. She married Willard Straight in 1911, and together they started The New Republic (1914) and took over a journal that became Asia (1917). Straight died in the flu epidemic of 1918; in 1925 Dorothy married Leonard Knight Elmhirst, a member of a landed English family. Although Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst returned to England to live, Dorothy continued her ownership and support of the magazines. Alice Winchester wrote: “Dorothy Elmhirst was the ‘angel’ who supported ANTIQUES through the perilous days of the Great Depression. Dealers in antiques could not afford to pay for advertising—and that was where the magazine’s income came from. Dorothy’s wealth . . . enabled her to pay the cost of publishing the magazine through those difficult days.”26

By July 1, 1929, ANTIQUES, along with its library, office equipment, and editor, had relocated to 468 Fourth Avenue in New York City. The Keyes family’s new home was a recently completed cooperative building on Sutton Place South designed by Rosario Candela, whose buildings were famous for their graceful neo-Georgian and art deco interiors.

Keyes continued to lead a breathtakingly busy life in New York, editing and writing for ANTIQUES and other periodicals, visiting dealers, and attending auctions and exhibitions. He belonged to numerous organizations and committees concerned with art and antiques and gave lectures on antiques both around New York and throughout the United States. During the summer he also traveled about the country to visit dealers, collectors, and ANTIQUES contributors, taking almost as much pleasure in food and cooking, it seems, as in antiques. Alice Winchester wrote that he “enjoyed equally the pursuit of elusive facts and of brook trout. He was as competent, and content, in his kitchen preparing epicurean concoctions, as at his editorial desk.”27 Rhea Mansfield Knittle, an expert on glass and the early arts of Ohio, wrote: “The last time I saw Homer Keyes was when he stopped off in Ashland [Ohio] from the West—en route to New York. He spent two happy days with us, insisted on cooking the breakfasts.”28 Shaker experts Faith and Ted Andrews recalled a visit with Keyes at their farmhouse in Richmond, Massachusetts, in August of 1938. “He took a lively interest, as all his friends knew, in the art of cooking,” they wrote. And at Shaker Farm, “he presided over the wood stove in the kitchen, concocting delicious meals from simple ingredients.”29

After a visit to antiques dealer and ANTIQUES contributor Julia Snow in Greenfield, Massachusetts, Keyes wrote her a letter of grateful thanks for the bag of edible treats she had sent home with him. The apple juice brought him great delight, which he expressed in vintage Keyesian style: “Ye apple juice . . . proves to be the finest of its kind that I have encountered—alluringly aromatic in itself and yielding none of the flavor suggestion of leaves, bark, and martyred insects, that most apple juice harbors.”30

Alice Winchester’s recollections, as well as existing letters and articles, indicate that Homer Keyes made these antiques-related trips alone, for Caroline Keyes’s interests lay in the area of charitable, rather than antiquarian, activities. The couple did go to Europe together quite often and Keyes took at least an occasional trip to Wyoming with his wife—probably to a dude ranch, for she was an enthusiastic horsewoman.

Caroline Abbott Keyes died in May 1938 and Homer Eaton Keyes followed her in October of that same year. Memorial tributes poured into ANTIQUES’ offices,

celebrating Keyes’s achievements and recalling his “discrimination, humor, and appreciation,” his embodiment of “rich culture and keen judgment, mellowed by experience and a naturally friendly character,” as well as his “powerful influence in maintaining high standards in the antiques field.” Keyes’s scorn of the “quest of the quaint” was truly vindicated by these admiring collectors, dealers, and scholars.31 Alice Winchester, after a brief period of staff reshuffling, became ANTIQUES’ editor. She often said that although she hadn’t realized it at the time, people later told her that Keyes had been grooming her to be his successor.

ELIZABETH STILLINGER was a longtime member of the ANTIQUES editorial staff, and is the author of several books on collecting, including The Antiquers (1980) and A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art 1876–1976 (2011).

1 Alice Winchester lecture, Bennington, Vermont, April 9, 1981. This and numerous other papers from the 1970s through the mid-1990s have been in my possession since Alice’s death in 1996, when her brother John was clearing out her apartment and gave them to me. I have kept them in anticipation of writing this article and intend to send them to the Archives of American Art to join the papers Alice donated in 1993. In this article they are hereafter cited as Winchester files.

2Picturing “A Real Attic” in ANTIQUES for May 1926, p. 300, where furniture, ceramics, textiles, and other antiques are stored,. Keyes declared that a “true attic [is] not entirely a place, not entirely a state of mind, but an agreeable mingling of the two as all true attics must be, and hence appealing to the dual nature of the lover of antiques.”

3These quotations are from comments Alice Winchester solicited for the January1942, twentieth-anniversary, issue of ANTIQUES: Swan, p. 71; Lyon and Kimball, p. 68. The “ephemeral competitors” Lyon refers to are, presumably, The Antiquarian, published from 1923 to 1934, and American Collector, published from 1934 to 1948.

4Willard Emerson Keyes (1861–1959) wrote nine articles for ANTIQUES between 1924 and 1939. Conrad Saxe Keyes (1874–1962) graduated from Columbia University and received his law degree from New York University. He was a partner at the law firm Wingate and Cullen and was elected president of the Brooklyn Bar Association in 1937. Rowena Keith Keyes (1878–1948) graduated from Mt. Holyoke College, received a master’s degree from Columbia, and a PhD from New York University. She was principal of Brooklyn Girls’ High School in the years before her retirement. Two other siblings, Ella (b. 1850), and Arthur (b. 1864), died too young to have made their marks in the world.

5The Red and Black, the Brooklyn Boys’ High School yearbook, 1897, pp. 18–19, accessed on e-yearbook.com, October 4, 2021. Although published for the first time in 1897, the yearbook contained information about Keyes and others in the class of 1895.

6Clipping from Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, November 1938, Homer Eaton Keyes file, Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College (hereafter Keyes file, Rauner).

7 Manchester Union, June 24, 1921, clipping, ibid. Even after he left Hanover, Keyes continued to consult on the design and decoration of Dartmouth College buildings.

His artistic abilities are on view in sketchbooks now in the Rauner Library. The earliest sketchbook, which dates from 1892, records the teenaged Keyes’s observations on family trips and excursions. Later ones contain his drawings of people, events, buildings, and objects in Germany, France, and Italy, made when he was studying and traveling in Europe from 1903 to 1905.

8Caroline Gardner Abbott was from a prominent and wealthy Cleveland family; she graduated from Vassar in 1899. Katherine Keith Keyes (1903–1954), Vassar, 1925, Columbia University, M.A. (psychology), 1928, never married. After graduating from college, she worked in the advertising departments of Scribner’s Magazine and Independent Woman and did editorial and promotional work for ANTIQUES from 1929 to 1939. In 1941 she stated on a biographical form for Vassar that she had recently completed a handbook on Oriental Lowestoft porcelain for beginners. Her article “Antiques Lead Down Diverse Paths” appeared in Independent Woman in December 1941.

9William Kilborne Stewart, “Homer Eaton Keyes,” Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, November 1938, pp. 13–14. The Keyes house was said to have been inspired by William Morris’s Red House, built in 1860 in Bexleyheath, southeast London.

10Carrick was the author of dozens of magazine articles and several books about antiques from the mid-1910s into the 1930s. Collector’s Luck, or A Repository of Pleasant and Profitable Discourses Descriptive of the Household Furniture and Ornaments of Olden Time (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1919) describes her adventures collecting antiques to furnish her house; The Next-to-Nothing House (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922) takes the reader through the house room by room. Kitty-cat Tales, a children’s book published in 1907, was illustrated by Homer Eaton Keyes and Bertha G. Davidson.

11Carrick, Collector’s Luck, p. 1.

12Ibid.

13Ibid, p. 158

14Ibid, p. 186.

15In the American Wing file on the Caswell carpet is a letter from The Magazine ANTIQUES dated October 15, 1934, and headed “POSSIBLY OF INTEREST.” It announces that ANTIQUES’ upcoming move from Fourth Avenue to 49th Street suggests the advisability of “disposing of some few articles of antiquity that have accumulated in the Editor’s Attic during the past ten years or so.” The letter was undoubtedly written by Keyes, who stated that the Caswell carpet, made by Zeruah Higley Guernsey Caswell of Castleton, Vermont, “is the most remarkable hand-embroidered American carpet known to the collecting world.” It hung on the wall in his Editor’s Attic, where it may be glimpsed on the left in Fig. 9. Because he thought so highly of it, I was astonished to read that Keyes was offering the carpet for sale for $2,500. The reason given was that wall space would be limited in the magazine’s new quarters. The carpet didn’t sell, and after Keyes’s death in October 1938, Katherine Keyes gave it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it has become one of the American Wing’s most prized pieces. I am indebted to Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator, Department of American Decorative Arts, American Wing, Metropolitan Museum, for providing me with a copy of the letter.

16The exception is Keyes’s publication and description of an eighteenth-century Hepplewhite sideboard he inherited from an aunt in “Little Known Masterpieces: IV: A Heppelwhite [sic] Sideboard,” April 1922, pp. 157–158.

17New York Times, March 10, 1913.

18“The Searchlight,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, date unclear, clipping in Keyes file, Rauner.

19ANTIQUES, January 1932, p. 9.

20Marion Atwood to William P. Evans of Salem, Massachusetts., April 30, 1969 (“never sent” noted on letter), Papers of Frederick E. Atwood, “Antiques History” folder, Rauner Library (hereafter Atwood papers).

21I am indebted to Amelia Peck for copies of correspondence relating to the Hart Room. A letter of June 14, 1936, from Sidney M. Mills to Joseph Downs, curator of the American Wing, states that Mills is billing the museum for the removal, documentation in architectural drawings, and packing and shipping of “two rooms Burnham Hart House, Ipswich, Mass.” to New York. A letter of October 23, 1936, from Martha Lucy Murray, owner of the “Burnham Hart House,” to Joseph Downs, thanks him for the check, indicating that the museum dealt directly with her in buying the room. Mills’s involvement in the actual sale is not mentioned. For a description and pictures of the Hart Room as it is installed in the American Wing, see Amelia Peck, “The Hart Room,” Period Rooms in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Harry N. Abrams, 1996), pp. 170-75.

22ANTIQUES, January 1932, pp. 9–10. Keyes names Esther Stevens Fraser, Rhea Mansfield Knittle, Harry Hall White, Helen McKearin, Carl W. Drepperd, Dr. Charles Green, Ruel P. Tolman, and Mabel M. Swan as writer/researchers whose work first appeared in ANTIQUES. Keyes devoted the Editor’s Attic of this issue to a tenth-anniversary history of the founding and subsequent progress of the magazine.

23Information about the business and financial side of the magazine is from Marion Atwood, Antiques Magazine Notes, Antiques History folder, Atwood papers. Marion Atwood’s account, which she said she compiled from scattered notes with Fred’s help, states that after supplying the original $1,500, Fred put in additional money to get the magazine going. He was paid back in full in January 1923.

24“Homer Eaton Keyes,” ANTIQUES, December 1938, p. 293. Winchester wrote that Keyes’s favorite among all the antiques he covered in the magazine was “Oriental Lowestoft”; his articles on the subject, which appeared in ANTIQUES from 1928 to 1937, “were the first to analyze and classify the ware in all its various types,” she wrote, “as well as to record its history completely” (introductory note to Homer Eaton Keyes, “Quality in ‘Oriental Lowestoft,’” reprinted in The Antiques Book [New York: Bonanza Books, 1950], pp. 19–26).

25Information about the sale of ANTIQUES is from a contract dated 1929 between Asia and ANTIQUES in the Atwood papers. Keyes characterized Asia as “both strong and sympathetic” in the Editor’s Attic, ANTIQUES, January 1932, p. 10.

26Undated handwritten note, Winchester files. Years later, in a letter dated December 28, 1983, to Dorothy’s son Michael Straight (ibid.), Alice wrote that Dorothy not only kept the magazine alive during the Depression, “she also established its unbroken tradition of complete editorial independence, which is the greatest treasure an editor can have.”

27“Homer Eaton Keyes,” ANTIQUES, December 1938, p. 293.

28Rhea Mansfield Knittle to Jean Lipman, September 13, 1943, Lipman papers, box 1 of 3, Art in America/Primitive Art, file no. 3, corres. 1943-45, Archives of American Art. Rhea Knittle (1883–1955), who wrote a great many articles on a variety of subjects for ANTIQUES, was “one of the first great early people to recognize Midwestern folk art—not just Ohio but folk art, period. She had a great collection . . . she loved the material and she understood it long, long before anyone else.” Bill Samaha phone interview with the author, July 18, 1996.

29Edward Deming and Faith Andrews, Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life: Memoirs of Fifty Years of Collecting and Research (Stockbridge, MA: Berkshire Traveller Press, 1975), p. 156. In an interview with me in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in the 1980s, Faith Andrews (1896–1990) recalled that she and Ted (1894–1964) had “wonderful fun” with Keyes and that he always said when visiting the farm “here there’s peace and quiet.”

30Homer Eaton Keyes to Julia D. S. Snow, undated letter, Julia Diadema Sophronia Snow papers, Memorial Libraries, Historic Deerfield. Snow was a well-known antiques dealer in Greenfield, Massachusetts, who wrote several articles for ANTIQUES, primarily on local subjects such as cabinetmaker Daniel Clay and pewterer Samuel Pierce.

31These comments and many others were published without attribution in ANTIQUES for December 1938, pp. 316, 318.