Alice Winchester was born in 1907 in Chicago, Illinois, the fourth of five children. Her father, Benjamin Severance Winchester, was a prominent Congregational minister and educator, the author of three books and numerous articles on religious education. Alice described him as “charming and . . . quite an innovative person [who] did a lot of interesting things in connection with the Congregational Church as a national movement. . . . And yet, he was no good at making money.” Because they were a big family, Alice said, they were always “kind of scratching and trying to get along on a little less than we’d like.” Nevertheless, she recalled her childhood as a happy one. Both her parents enjoyed their children, she said, “and we enjoyed them.”1

Pearl Adair Gunn, Alice’s mother, was born while her family was journeying west from Kentucky to Walla Walla, Washington, where her father, also a Congregational minister, was to take up a position. She grew up there and, unusually in those days for a girl from the West, attended Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, graduating in 1895. When she married Benjamin Winchester in 1897, Pearl began a life characterized by frequent moves. From Chicago, the family relocated to Concord, Massachusetts, where Alice attended kindergarten through second grade at “a delightful school on a very nice farm.” New Haven was next—her father taught religious education at Yale for a few years before settling in the Greenfield Hill section of Fairfield, Connecticut. There Alice attended Roger Ludlowe High School, where she began her editorial career by founding and editing the school paper. She graduated as class valedictorian in 1925, then followed her mother and three older sisters to Smith College.2

In her second year Alice signed up for Smith’s recently instituted junior-year-abroad program with the goal of studying in France and becoming fluent in the language. She attended classes at the Sorbonne in Paris while living with a doctor’s family on the Left Bank. They included her in all their trips, parties, and other activities, so she soon felt she was, in fact, a member of the family. She achieved her goal of fluency, saying that before long, speaking French “came naturally and I could dream in it.”

Alice returned to Smith for her final year; she graduated in 1929, having won the Old French prize and a Phi Beta Kappa key. She moved to New York to get a job and share an apartment with her sister Polly, a teacher and artist. “It was exciting— thrilling—living in New York,” she recalled. She and Polly were interested in the new forms and styles of modern art, and visited museums and galleries on Saturday afternoons (Saturday morning was part of the workweek). They went to the theater at least once a week, sitting in balcony seats they bought for a dollar each.

“I had no kind of office training whatever,” Alice said. “I went to employment agencies and they’d say, ‘what can you do?’ And I’d say, ‘I’ll do anything.’” But since she could neither type nor take dictation, few jobs were open to her. She settled for one as a file clerk at Chase National Bank, and though she was proud of working at what was then the largest bank in the world, she soon realized that, to advance, she needed additional skills. She signed up for a night-school course to learn typing and dictation and had almost completed it when a French friend working in New York told her that ANTIQUES was looking for a secretary. “This was a roundabout but beautiful coincidence,” she said, “that my Paris year was putting me in touch with a job in New York.”

She was hired in Homer Eaton Keyes’s absence, and when he returned from summer vacation, she said: “I quite fell for him. . . . He was a charming person, very sympathique, very appreciative, didn’t seem to mind that I was a greenhorn. In fact, it appealed to his own tutorial background . . . here was a fresh pupil for him. . . . I thought I’d learned a good deal about art at Smith and in Europe, but I didn’t know anything about a ladder-back chair.”

At first, her duties were primarily stenographic— she took dictation and produced acceptable letters, typed “yards and yards” of manuscripts, and made final copies of Keyes’s edited articles. As time went on and Keyes saw that she was genuinely interested in antiques, he began to use her, she thought, “as a sample of his public—did I think, for example, that this or that article explained its subject satisfactorily.” And it wasn’t long before they were working as a team.

Looking back on this period, Alice described the way things were in 1930, when she went to work for Keyes:

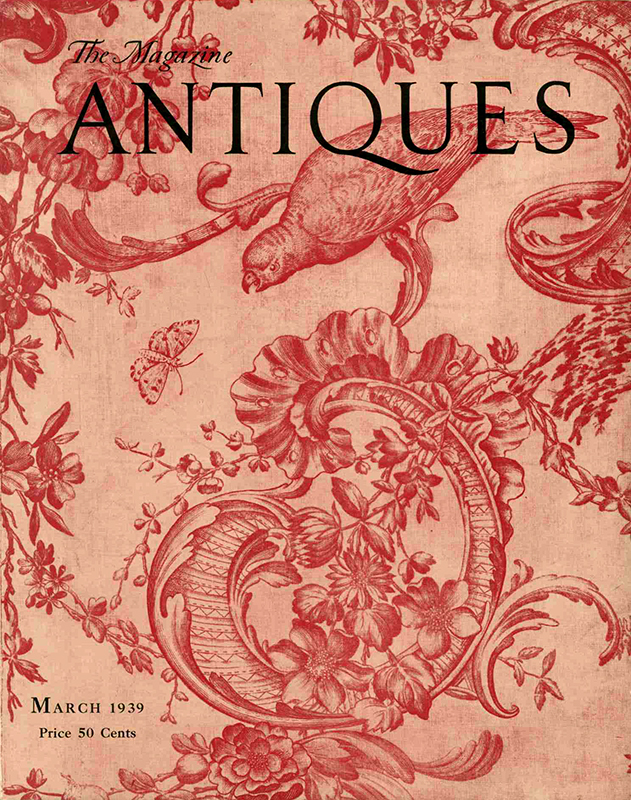

The Magazine ANTIQUES was a small, young periodical created to provide some kind of link among those people interested in the American decorative arts. They were relatively few then, and scattered, and had no meeting place or means of communication. They were usually considered a little odd, too; who but an eccentric would have any interest in those old relics called American antiques? Letters and questions arrived regularly and some became long-standing jokes around the office—like the one from a woman who had been disappointed at the cutlery store because they had no Currier knives . . . and the one who wanted to know where to find china in the Mice and Onion pattern.

While he very much enjoyed such communications, Keyes’s vision for the magazine was entirely serious. Alice stressed that he trained the staff to take a scholarly, not sentimental, approach and that “we had a certain sense of mission to disseminate [accurate] information.”3 She continued to feel this sense of mission throughout her thirty-four-year editorship, during which the world of American antiques expanded enormously. She noted, for example, that in her early days at the magazine the date 1830 was set firmly in stone as that after which an object no longer qualified as “antique.” By the second half of the twentieth century, however, this date had been pushed forward by more than a hundred years. Collectors proliferated and the study of antiques increased greatly, as did the related study of historic preservation, whose growth was both symbolized and stimulated by the founding of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1949. Regional studies expanded, too, with a greater understanding of the interrelationships among different regions of the United States and between the US and other countries. Alice saw that all these changes were reflected in ANTIQUES.

Alice wrote in 1972 that when Homer Keyes died in 1938, the other member of the editorial department was Dorothy Chamberlain, who handled design and production. Immediately after Keyes’s death, Alice wrote, “she and I were made co-editors, both of us young and green and scared. Within a few months, she decided to go back to a large magazine on which she had worked before and I was left at the editor’s desk.”4 As she became more comfortably settled in the editor’s chair, Alice began to put her own stamp on the magazine. She never strayed from Keyes’s founding principles but she branched out into series like Living with Antiques and its companions History in Houses and History in Towns, which focused on ideas about collecting, using, and preserving antiques and architecture. It wasn’t that such articles were new—there were earlier ones on interiors in private homes and on antiques-appointed historic houses. The difference was that such articles were no longer infrequent and scattered, issued under a variety of titles and layouts, but were now published within uniform formats.

The Living with Antiques series, especially, received an overwhelmingly enthusiastic reception. Alice wrote in 1950, “From the many comments we receive, we know that our Living with Antiques series is the bestread feature in the magazine. Everyone loves to see how other people live.” Looking back over the years after her retirement, she said, “I feel that the title ‘Living with Antiques’ pretty much belongs to me. I created it years ago for a book, then a series of articles in ANTIQUES, then lectures.”5

Not long after becoming editor Alice diverged from Keyes’s path—though not his principles—by devoting time and energy to books as well as articles. The first Living with Antiques book, published in 1941, is little known today.6 It contained articles that treated various aspects of the subject but had not been published under the title “Living with Antiques.” In the spirit of Alice Van Leer Carrick’s books, this first Living with Antiques encouraged readers to furnish their homes with antiques—and showed them how. Articles on antiques-furnished houses were supplemented by short chapters on specific rooms and spaces—dining rooms, halls, “nooks and corners”— and types of objects—cupboards and their contents, beds, mirrors—giving prospective collectors ideas and suggestions. In her introductory essay, “Antiques to Live With,” Alice pointed out that the person who lives with antiques is not necessarily a collector, but may be a “selector,” choosing from the great variety of available styles and types of antiques. She encouraged beginning collectors by assuring them that “There are no fixed rules to govern living with antiques.”7 This first Living with Antiques is informative, interesting, and fun to read. Later on in the 1940s, “Living with Antiques” articles began to appear under that title and by the time the second Living with Antiques book was published in 1963, the collected articles appear in a consistent format.8

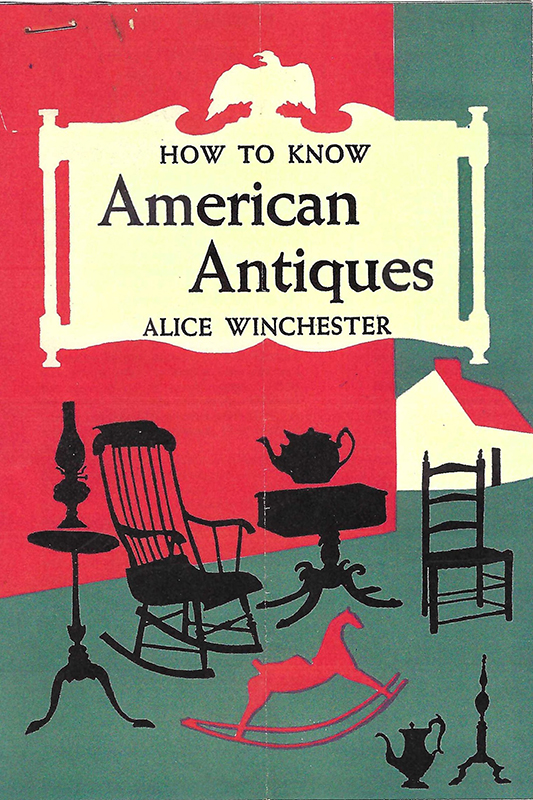

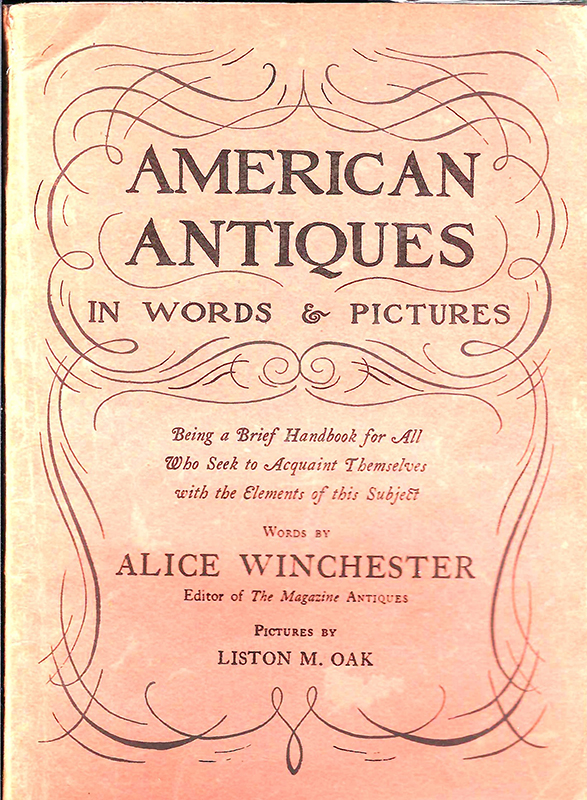

Next came American Antiques in Words and Pictures, by Alice Winchester with illustrations by Liston Oak, published in 1943 (Fig. 22).9 This was a little paperback primer on the subject of American antiques, covering furniture, silver, pewter, glass, and ceramics. Like the 1941 Living with Antiques, it is almost forgotten today. Alice’s subsequent How to Know American Antiques, of 1951, covered the same material but expanded and updated (Fig. 19).10 Happily, it achieved the popularity that had eluded its predecessor: enormously positive reviews hailed the pocket-sized volume as the first to provide a handy and affordable survey of the antiques made and used in America up to 1900. One reviewer called it “more than a handbook; it is a fascinating story, with dates, definitions and a plausible continuity. . . . A delightful way to bring to life America’s lively past,” and another labeled the paperback edition “the best thirty-five-cents buy in the book stalls today.”11 It became a standard introduction to MARCH/APRIL 2022 the subject, with half a million copies sold by the mid-1970s. Alice told me that for many years royalties from How to Know American Antiques paid for her winter vacations in the Caribbean.

The Antiques Book, of 1950, contained a collection of seminal articles published in ANTIQUES from the 1920s through the 1940s. These covered eleven different collecting categories, and included basic surveys, summary, and critical articles, as well as some that read like detective stories. Many authors of the chosen thirty-five selections (out of twenty-five hundred) were by 1950 famous in the antiques universe, and all of them, wrote Alice, “have made an important contribution to our understanding of antiques.”12

In 1959 came The Antiques Treasury, which presented seven American museums whose collections had been featured in ANTIQUES: the Winterthur Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, the New York State Historical Association, Historic Deerfield, and the Shelburne Museum. A general essay on each institution was accompanied by separate discussions of its most important holdings. Reviewer James D. Van Trump pronounced this a book for the “cultivated, but hurried, reader—scholarship without tears and history without boredom.”13

Collectors and Collections followed in 1961. Subtitled “The ANTIQUES anniversary book with a sampling of internationally famous collections,” this was, as Alice Winchester put it, “a birthday present for our readers.” Celebrating the magazine’s fortieth birthday, the book contains articles on antiques from all over the world and on the people who lived with them during ANTIQUES’ first four decades. In a departure from its earlier practice of gathering previously published articles in books such as Living with Antiques and The Antiques Treasury, the text and illustrations were prepared specifically for Collectors and Collections. The featured collections ranged from that of Ima Hogg’s Bayou Bend, furnished with choice American antiques in Houston, Texas, to that of the Château d’Ormesson, built on the outskirts of Paris in the late sixteenth century. The chateau, furnished with eighteenth-century French antiques, was occupied by a member of the eleventh generation of the Ormesson family.

In 1963 the second Living with Antiques came out, describing and illustrating forty homes that had appeared in ANTIQUES during the previous decade. The book was a decided contrast to its predecessor of 1941 in displaying homes that, although varying widely in style, furnishing, and location, presented a homogeneous appearance. This was undoubtedly due to the influence of the period rooms in the Metropolitan Museum’s American Wing, which opened in 1924. Until then, most Americans had experienced “antiques” as a jumble of oddities in dusty cases or on exhibition tables at fairs. A Queen Anne chair was more likely to be displayed alongside teeth said to have belonged to George Washington and the skeleton of a fish from the Amazon, than with other early American furnishings. A major intention of the American Wing period rooms was to contextualize American antiques—to show that they were not curiosities. A room furnished entirely with, say, Queen Anne or Chippendale pieces (to use labels contemporary with the rooms) provided a vivid three-dimensional picture demonstrating that these antiques— whether of wood, clay, glass, or metal—had been made in the same style at the same time to be used in rooms of that same style.

Such rooms set a widely followed example for collectors. Interiors illustrated in the 1963 Living with Antiques thus exemplified period-room consistency of style, frequently giving them the tooorderly look of museum settings. This held as true for interiors in Ohio, Wisconsin, South Carolina, and California, as in urban centers like New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, all of which were represented in the book. It was the last of the books Alice wrote or edited while she headed ANTIQUES.14

“If the 1920s, following World War I, became a golden age of collecting,” Alice said in a lecture in 1982, “the period following World War II was a second golden age, a time of great activity on the part of collectors and museums, and of vastly expanding interest in American antiques. It was a very exciting time in my own life with ANTIQUES— and I learned that collectors were as interesting as antiques.”15 In 1948 a new project came along that was to provide Alice with the opportunity for more interaction with the collectors she already knew, to meet many she didn’t, and to engage the interest of collectors-to-be. It was, as well, another way in which she saw a chance to lead the magazine into new territory. The idea—a symposium or forum on the subject of antiques—originated with Colonial Williamsburg, whose director of interpretation, Edward Alexander, asked Alice and ANTIQUES to join with him and his colleagues in creating such an event.

The first Williamsburg Antiques Forum, sponsored jointly by Colonial Williamsburg and ANTIQUES, opened in early 1949. It provided a place for collectors, scholars, and dealers to meet and exchange views in person as, more than a quarter of a century earlier, ANTIQUES had provided a place for them to meet in print. The five-day forum offered lectures in the morning, tours of Colonial Williamsburg’s houses and collections in the afternoon, and entertainment such as candlelit receptions and concerts in the Governor’s Palace in the evening.

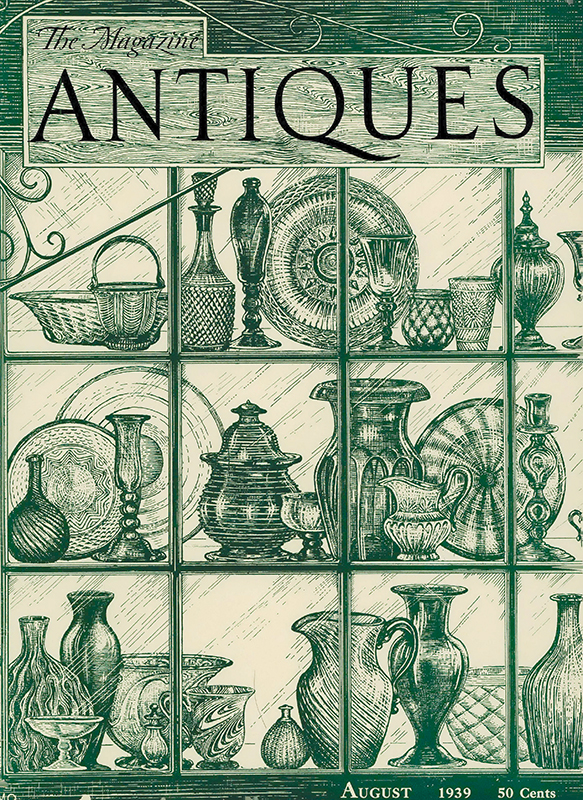

Fig. 14. ANTIQUES cover for August 1939 showing A Window of Old Glass, a drawing by Liston M. Oak (1895–1970), then associate editor of the magazine. Alice wrote in the Editor’s Attic that this was the fourth issue of ANTIQUES to be devoted entirely to glass, a tradition begun with the August 1933 issue.

Alice remembered that not all evening activities were so sedate and respectable, however. After-hours sociability could progress from spirited to raucous, especially among those also enjoying a nightcap or two. These choice spirits sometimes engaged in such high jinks as pillow fights and three-legged races in the hallways of the staid Williamsburg Inn. Alice never disclosed whether she knew about these capers from personal experience or hearsay.

For the most part, forum lecturers were chosen from experts on the Colonial Williamsburg and ANTIQUES staffs and from the magazine’s contributors. The cost of the 1949 forum per person, per session (there were two), including registration, accommodations, and meals, was $85 for the elegant Williamsburg Inn, and $60 for the less luxurious (but still very nice) Williamsburg Lodge. Enthusiasm—and registration—for the proposed event astonished the planners: 290 people signed up for the first session, 271 for the second, and registrants were from almost every state in the union. One enrollee wrote, in a note representative of many, “This is a marvelous idea, and we are looking forward to being there.”16

The first Antiques Forum was a great success and became an eagerly anticipated annual event. It provided up-to-date information about antiques, art, and architecture (which very often subsequently appeared as ANTIQUES articles). In addition, it offered multiple opportunities for attendees to interact with leading scholars, curators, and others in antiques-related fields. Old friends reunited and many new friendships developed during the event. More broadly, the Williamsburg Antiques Forum became a model for seminars and forums throughout the country. It was a landmark in the history of collecting in America, and a major sign of the new era in which the tremendous expansion of the antiques collecting field took place.17

An important development in American furniture scholarship stemmed from a remark a lecturer made at the 1949 forum. He dismissed the whole subject of southern furniture, saying that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.”18 The statement so inflamed one member of the audience that she inquired caustically whether it had been made “out of prejudice or ignorance.”19 It caught the attention of many other listeners as well, most notably Helen Comstock of ANTIQUES, who took the “little of artistic merit” assertion as a challenge and conceived the idea of a loan exhibition of furniture with a verifiable southern history. Alice and ANTIQUES’ staff fully supported this enterprise, as did Colonial Williamsburg. Leslie Cheek, director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, offered to hold the exhibition there. To further support Helen’s initiative, Alice announced that ANTIQUES “would focus attention on the antiques and craftsmanship of the South” throughout 1951.20 The 1951 Antiques Forum also concentrated on the South, presenting talks on southern furniture and houses, and offering tours of Virginia plantations.

Three years of research on the part of Helen Comstock and numerous others culminated in Furniture of the Old South 1640–1820, which opened at the Virginia Museum in January 1952 to coincide with the 1952 Antiques Forum, whose theme was, of course, southern furniture. The January 1952 cover of ANTIQUES read simply, “The Magazine ANTIQUES/ 30th Anniversary/ Edition Featuring/ Furniture of the/ Old South 1640–1820.” Noting that from the beginning one of ANTIQUES’ main concerns had been the regional characteristics of American furniture, Alice declared that this issue was “the permanent record of the Exhibition, offering the most thorough analysis of southern furniture yet published.” It served as the catalogue to the exhibition and much of it, said Alice, was the work of Helen Comstock. Without her: “The Exhibition itself would never have been. Equipped with an exceptionally profound knowledge of antiques, she has uncovered in southern furniture a new field of unsuspected richness, and laid the foundations on which all future students of the subject must build.”21 The southern furniture exhibition proved to be another milestone in American decorative-arts history. One of its most important results, according to Alice, was the founding of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which opened to the public in 1965.

The Antiques Forum promoted widespread awareness of both ANTIQUES and Colonial Williamsburg, and Alice Winchester’s essential role in organizing it made it one of the highlights of her career. She became an increasingly prominent and well-known figure in the world of antiques. She was asked to lecture by museums and other organizations all over the United States and this put her in touch with curators, collectors, and dealers she hadn’t known before. “I broadened my acquaintance . . . very considerably,” she said, thus providing the magazine with ever more sources of articles.

In the 1950s, she once told me, Alice was part of a group of up-and-coming antiques professionals that included Joseph Downs of the American Wing, Louisa Dresser of the Worcester Art Museum, Charles Montgomery, director-to-be of the Winterthur Museum, Ruth (“Petey”) Davidson of ANTIQUES, and Ruth’s husband, Marshall Davidson of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Alice called these professionals “Young Turks,” not in the sense of advocating violent revolution, but of forging ahead into new areas of research and study. They “were all interested in the same things and were all very congenial and anxious to share their information and enthusiasm with one another and the public.”

Another elite group to which Alice belonged in the 1950s was organized by the antiques dealer J. A. Lloyd Hyde. He decided, Alice said, to get some of his many collector friends together so that they could get to know one another.22 The principal members of this crowd were Electra Havemeyer Webb, Henry and Helen Flynt, Katherine Prentis Murphy, Maxim Karolik, Ima Hogg, Louise Crowninshield, Bernice and Edgar Garbisch, and Ralph and Cynthia Carpenter. Among what Alice called the lesser lights were “certain dealers, curators, and me.” Henry du Pont, she added, “was not exactly a member of the group though he joined in sometimes—and he was ever present as the ideal and mentor.” House parties at these collectors’ homes and/or museums took place in, for example, Deerfield, Massachusetts; Shelburne, Vermont; Houston, Texas; and at Pokety, the Garbisches’ estate on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The group gathered, as well, at dinner parties in and near New York. These were glittering social events at which participants “took delight in entertaining each other beautifully amid their collections, using and enjoying their precious antiques, serving luxurious meals on eighteenth-century porcelain and silver.” Alice reflected that “in a way it was a kind of playing house, but a very sophisticated and appreciative kind.” Guests toured the premises and admired the proud host’s latest acquisitions. Much of the talk was about antiques, Alice said, with exchange of information and gossip, and “a certain amount of friendly competition.”23

Such get-togethers exemplify the tight-knit, clubby character of the culture at the very top of the American collecting scene in the mid-twentieth century. Members of this group, most of whom were planning to turn their collections into museums, felt themselves to be, like Alice’s Young Turks, pioneers in the field. For Alice, such occasions were a chance to keep up with what these collectors were doing and to publish their most exciting finds.

Meanwhile, in Cooperstown, a charming village on Lake Otsego in central New York State, the idea of a forum had turned into a two-week Summer Seminar on American Culture in 1948. It was sponsored by the New York State Historical Association (NYSHA), whose Fenimore House held a collection of American folk paintings and sculpture, and whose Farmers Museum and Village Crossroads, an outdoor museum created with early New York State buildings such as a school and a country store, presented a picture of rural life in an earlier New York State. In 1949 and for several years thereafter American folk art was a featured subject of the seminar. In emphasizing the arts and crafts of the middle class, the Cooperstown seminars presented a useful contrast to the Williamsburg Antiques Forums, whose focus was wider, taking in the—often elite—arts of colonial America and of the European and Asian countries from which Americans imported many kinds of household goods.

“In the early 1950s,”Alice recalled, “several Cooperstown seminars were devoted to American folk art and I participated in them along with Nina Fletcher Little and Jean Lipman.” Both Little and Lipman were leading folk-art specialists and collectors, good friends of Alice and contributors to ANTIQUES. Nina Little became a particularly good friend, perhaps the one person among the folk-art collectors of her generation Alice most valued. She had first met Nina in ANTIQUES’ offices when she came in to consult Keyes about an article. Nina took an immediate liking to Alice and began to invite her to visit her and her husband, Bertram K. Little, in Brookline and at the Littles’ farm, Cogswell’s Grant, in Essex, Massachusetts. Both houses were filled with fascinating New England folk art of all kinds. “Nina taught me a great deal,” said Alice many years later, “and influenced my taste and broadened my horizons. For fifty years and more she was one of my closest and dearest friends.”24

Beginning her research into New England’s folk art and artists in the 1930s, when the field was almost untouched, Nina Little uncovered the identities of dozens of artists. She was as much a historian as a collector, and she recorded her findings on folk and other art in forty-six articles for ANTIQUES, and in several books. In her introduction to her Country Arts in Early American Homes, Nina explained that while much had been written about the household furnishings of America’s elite, “Less familiar, perhaps, are the personal possessions of the yeoman class, where these were kept, how they were used, and what variety of domestic goods was conveniently obtainable in rural America from 1750 to 1850.”25 It was these things that she and Bert collected and that she talked about at the Cooperstown summer seminars and elsewhere. Alice remembered those Cooperstown seminars as great fun and very lively. The subject of folk art was new and fresh, she said, and “we were all delightfully personal and unprofessional about it: we didn’t talk about esthetic values and basic concepts but we’d say that a painting or carving had zip or zing or real oomph. And we’d discuss endlessly the question What is American folk art?”26 Nina Little, to provide her own answer to that question, and in proof of Alice’s assertion that these early seminars were personal, arrived one summer prepared to illustrate her talks “with 22 pictures, 6 unframed water colors, and 2 sketch books” from her own collection.27

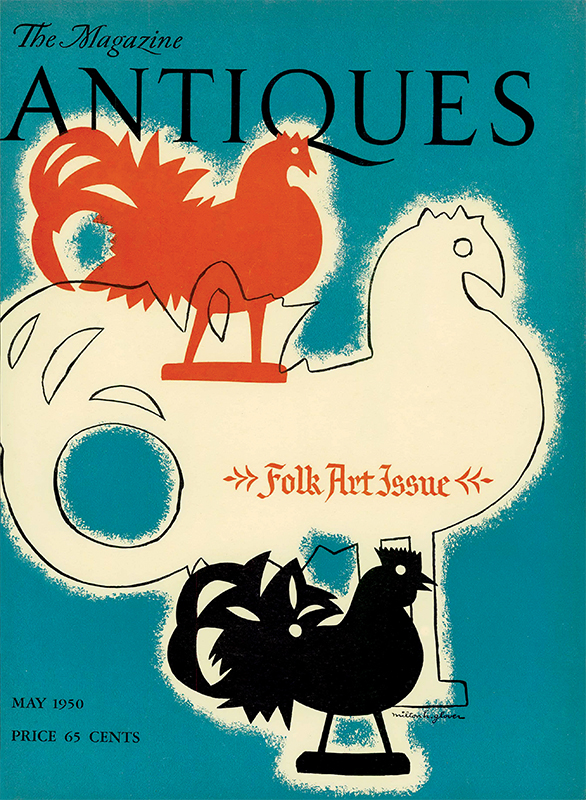

Alice Winchester was not a collector of antiques, as she often said, but “a collector of collectors.” She was, however, a very interested and inquiring student of folk art, as well as of other decorative arts. Although Homer Keyes had published articles on folk art, it was not one of his major interests. It did become one of Alice’s, and she published many articles on many aspects of folk art, and for the first time devoted a whole issue— that of May 1950—to the subject (Fig. 13).

Jean Lipman and her husband, Howard, were most definitely collectors. Their first folk-art collection was, in fact, purchased by NYSHA’s chairman of the board, Stephen C. Clark, in 1950, and formed the nucleus of the Fenimore House collection. After that sale, the Lipmans began collecting again. This time they made a specialty of painted furniture, although they continued to acquire folk paintings and sculpture. Like her mentor, Frederick Fairchild Sherman, founder of Art in America, ANTIQUES contributor, and collector of American folk art, Jean investigated the origins of pieces she acquired. She contributed new research—sometimes published in ANTIQUES and sometimes in Art in America, which she bought after Sherman’s death in 1938— on a number of folk artists.28

Perhaps as a result of working together on the Cooperstown summer seminars, Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester co-edited Primitive Painters in America 1750–1950, an anthology of articles on individual folk painters.29 They worked together on other projects over the years as well, wrote articles for one another’s magazines, and were co-curators of the outstandingly successful and influential exhibition and catalogue, The Flowering of American Folk Art, held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974.30

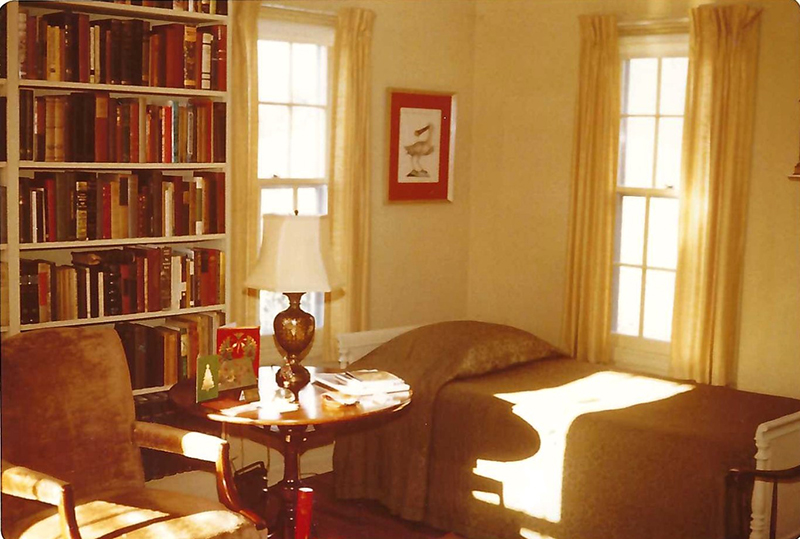

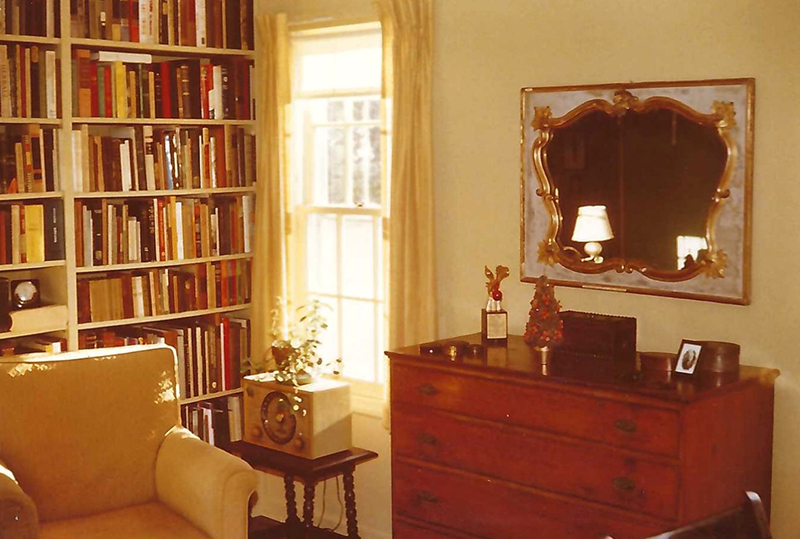

ANTIQUES’ owners, now represented by Dorothy Elmhirst’s son Michael Straight, had a strict retirement policy: when you turned sixty-five, you retired. So, in July of 1972, Alice vacated the editor’s chair and joined her sisters Margaret and Polly at the family’s longtime home in Newtown, Connecticut (Figs. 2, 8–10). She continued her participation in the antiques community, remaining active on boards and committees and engaging in antiques-oriented projects. Two of the most absorbing were her book Versatile Yankee: The Art of Jonathan Fisher, 1768–1847, published in 1973, and, the following year, the landmark exhibition and catalogue The Flowering of American Folk Art, mentioned above.31

Without straying from Homer Eaton Keyes’s principles and policies, Alice Winchester masterfully guided ANTIQUES through a period of unprecedented expansion and change. She investigated new developments as they occurred and enlarged coverage of existing subjects when required. Her own personal interest, as we have seen, was in the collectors rather than the collections, a preference particularly obvious in her Living with Antiques series. She emphasized this human side of collecting in a talk to young decorative-arts students: “While this is a field concerned with things,” she said, “it is the relation of those objects to people that give the things meaning.”32 Whereas for Keyes it was the antiques—the objects themselves—that inspired him to establish ANTIQUES, for Alice it was the collectors, preservers, and caretakers of antiques that inspired her to nurture and sustain ANTIQUES, and to lead it toward new horizons.

1 Robert Brown interview with Alice Winchester, September 17, 1993, July 28, 1994, and June 29, 1995, Danbury, Connecticut, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. Unless otherwise noted, quotations from Alice Winchester throughout this article are from this AAA interview; I have edited them lightly for clarity. 2 Alice’s siblings were Margaret (c. 1898–1995), Katherine “Kay” (b. c. 1900), Pauline “Polly” (1904–1990), and John (1914–2002). Margaret and Alice never married. Polly married Robert Greene Inman; they had no children. Both Kay and John married and had children. 3 Alice Winchester, introductory address, Northeast Antiques Forum, Rockport, Maine, August 17–19, 1978, Winchester files; as noted in Part I, these are files currently in my possession. 4 ANTIQUES, January 1972, p. 147. 5 Ibid., June 1950, p. 431. The second quotation is from “Living with Antiques: A Personal Perspective,” a lecture Alice gave at “Hudson Valley Holiday,” Mohonk Mountain House, New Paltz, New York, June 1, 1982 (hereafter “Hudson Valley Holiday”), Winchester files. 6 Living with Antiques, ed. Alice Winchester (New York: Robert M. McBride and Company, 1941), with a foreword by Joseph Downs. 7 Ibid., p. 12. 8 Living with Antiques: A Treasury of Private Homes in America, ed. Alice Winchester and the staff of Antiques Magazine (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1963).9 Alice Winchester, American Antiques in Words and Pictures (New York: the author, 1943). Liston M. Oak was an artist, journalist, and activist in liberal politics. He was associate editor of ANTIQUES from 1939 to 1943. 10 Alice Winchester, How to Know American Antiques (New York: New American Library, 1951). 11 The first quotation is from the Newtown Bee, June 29, 1951, the second from the Jewish Advocate, July 5, 1951. Both are clippings from a scrapbook in the Winchester files. 12 “Introduction,” The Antiques Book (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), np. 13 Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, vol. 43, no. 3 (September 1960), p. 296. 14 ANTIQUES did have a contract with Dutton for another book, which was to be an updated version of Alice’s How to Know American Antiques, presented in a format based on Helen Comstock’s “Chronology of Crafts,” an outline of the chronological development of style published in The Antiques Treasury. When she signed the contract with Dutton, Alice was expecting that she and the staff would produce the book while carrying on with monthly publication of the magazine, as they had in the past. Times had changed, and it turned out that there was too much day-to-day work to allow for the production of a new book, so Alice asked me to write it. The ANTIQUES Guide to Decorative Arts in America 1600– 1875, by Elizabeth Stillinger with an introduction by Alice Winchester and line drawings by Pauline W. Inman (Alice’s sister Polly), came out in 1972 (New York: E. P. Dutton and Sons). 15 “Hudson Valley Holiday” lecture. 16 This note was from Avis Gardner, wife of legendary antiques dealer Rockwell (“Rocky” to all) Gardner, of Stamford, Connecticut (reel CC-003-007-0891.jpg, Colonial Williamsburg Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia). Many thanks to Sarah Nerney, associate archivist, Colonial Williamsburg, for checking facts about the Antiques Forum and for copies of the program and related material, including this quotation. 17 Alice Winchester and ANTIQUES continued to sponsor the forum with Colonial Williamsburg for the next ten years. 18 This remark has been attributed to Joseph Downs (see Luke Beckerdite, “Introduction” in American Furniture, Chipstone Foundation, 1997, available at chipstone.org, accessed November. 24, 2021), but a transcript of Downs’s lecture in the Colonial Williamsburg Archives contains no reference to southern furniture (Colonial Williamsburg Archives, Pamphlet file 1927–1973, Publications—Antiques Forum [folder 2]). If Downs did make this remark, it may have been an off-the-cuff response to a question after the lecture. I am most grateful to Sarah Nerney for searching out this transcript and sending me a copy. 19 Beckerdite, “Introduction” in American Furniture. 20 ANTIQUES, January 1951, p. 35. 21 Ibid., January 1952, p. 39. 22 In her handwritten notes for informal remarks at a Winterthur Friends event, April 22–23, 1989 (Winchester files), Alice called Lloyd Hyde “a dealer of a special sort,” by which she meant, I think, that he had friendships as well as business relationships with many of his clients. Lloyd Hyde’s specialties were Chinese export porcelain, antique lighting devices, and rich old European fabrics, but he supplied many other kinds of antique accessories to his customers, who included, importantly, H. F. du Pont. See Jennifer Carlquist’s admirable master’s thesis for a complete treatment of Hyde’s life and times: “The Antiquarian Career of J. A. Lloyd Hyde: Americana as business and pleasure” (Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum/Parsons, the New School for Design, 2010). 23 Alice Winchester to Michael Kammen, July 6, 1981, Winchester files; and Bennington lecture, April 9, 1981, ibid. 24 Alice Winchester lecture, “Aura of the Early Years,” probably given at Sotheby’s workshop on the Little collection in New York City, October 3, 1994, Winchester files. 25 Quoted in Elizabeth Stillinger, A Kind of Archeology (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), p. 134. Not all Nina Little’s research was published in ANTIQUES; she wrote for other publications such as Art in America as well. 26 Alice Winchester lecture, “The Flowering of American Folk Art,” New York State Historical Association, Cooperstown, New York, July 8, 1974, Winchester files. 27 Quoted in Stillinger, A Kind of Archeology, p. 336. 28 For more on Jean and Howard Lipman, see Ruth Wolfe, “Profile: Jean Lipman,” Antiques Journal, March 1989, pp. 10– 12, 62–67; and Stillinger, A Kind of Archeology, pp. 204–218. 29 Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester, Primitive Painters in America 1750–1950 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1950). 30 Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester, The Flowering of American Folk Art (New York: Viking Press in association with the Whitney Museum, 1974). 31 Alice Winchester, Versatile Yankee: The Art of Jonathan Fisher, 1768–1847 (Princeton, NJ: Pyne Press, 1973). 32 Alice Winchester, “Address to the Deerfield Summer Fellows,” August 12, 1977, Winchester files.

ELIZABETH STILLINGER was a longtime member of ANTIQUES’ editorial staff, and is the author of several books on collecting, including The Antiquers (1980) and A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art, 1876–1976 (2011).