Photography by Alan Kolc

We may thank the Industrial Revolution for many things, not the least of which may be the contrarian William Morris and his reform movement followers who prized man over machine and fostered our enduring admiration for handicraft, at the heart of modern antiquarianism.

The legacy of Morris inclines us to think of makers and manufacturers as occupying hostile camps, the makers having the moral edge in a conflict that will be won, in the economic sense, by the manufacturers. In truth, the imaginative flourish that produces an automobile where before there was only a wagon is much like the spark that yields words on a page or brushstrokes on canvas.

The legacy of Morris inclines us to think of makers and manufacturers as occupying hostile camps, the makers having the moral edge in a conflict that will be won, in the economic sense, by the manufacturers. In truth, the imaginative flourish that produces an automobile where before there was only a wagon is much like the spark that yields words on a page or brushstrokes on canvas.

In suburban Philadelphia, art and industry are joined in a residence commissioned in 1901. The house represents the union of William Lightfoot Price, the Philadelphia architect who created a utopian arts and crafts community in Rose Valley, Pennsylvania, but earned his living designing resort hotels and houses for the carriage trade, and his client Louis Semple Clarke, an inventor and engineer who founded what became the Autocar Company.

Like its sponsorship, the gabled, slate-roofed house is a hybrid (Fig. 3). Its foundation of native Wissahickon schist, soft enough to record the passage of time and glinting in the sun, is capped by half-timbering and stucco meant to evoke, in a vague sense, the charms of old Europe. Architectural historian George E. Thomas, author of the monograph William L. Price: Arts and Crafts to Modern Design (2000), counts the residence among the most successful historicist designs by Price, whose premature death curtailed his modernist inclinations.

A century after its completion, the house, suffering benign neglect at the hands of successive owners, was showing its age. The exterior woodwork was rotting and chimneys were crumbling. The piping was sclerotic. In 2008 a couple who had ventured around the world before returning to the husband’s home state acquired the house and began a meticulous restoration of the faded beauty, a showcase for their growing collection of American art. “We walked in and thought, at last, a place for our Tiffany glass. It traveled with us to London and Tokyo but we were seldom able to display it. This house is built for it,” the wife says.

The couple moved into a nearby rental as the eighteen-month renovation got underway. Referring to Price’s original plans and period photographs, some supplied by a Clarke granddaughter, the project team led by Archer and Buchanan Architecture delivered award-winning results.

Will Price’s signature is everywhere in the house, from leaded windows decorated with jousting knights on horseback (see Figs. 2, 6) to decorative carving, possibly by John Maene, the Rose Valley shop foreman, on the interior woodwork. The photographs the couple consulted so often suggest that Clarke admired Price’s work but absorbed little of the progressive ideals underpinning it. Far from furnishing his home en suite with furniture, pottery, and metalwork handmade by the Rose Valley craftsmen, Clarke decorated with a miscellany more typical of his time. He lived with Tiffany glass and Craftsman furniture by Gustav Stickley, prompting the current owners to purchase a hexagonal library table of about 1905 still bearing Stickley’s paper label.1

Original to the house is a Rose Valley oak trestle table (see Fig. 4) that closely resembles one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Designed by Price and bearing the distinctive Rose Valley brand, a five-petaled rose superimposed by a V and enclosed in a buckled belt inscribed “rose valley shops,” both tables have mortise-and-tenon joinery and are hand-carved with Gothic tracery and figural mortise pins.

At Rago Arts and Auction Center in 2012, the owners purchased a Rose Valley oak and leather-upholstered open armchair (see Fig. 1), also designed by Price and carved with monkeys and dragons,2 along with wrought-iron fireplace forks from Arden, a utopian community cofounded by Price in Delaware.

Ironwork by Samuel Yellin-who, like Price, studied at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Arts and subsequently taught there-is a more recent interest of the collectors, who have purchased a pair of 1920s wrought-iron gates with dragon’s head finials (see Fig. 7) and an S-curve sample piece of about 1921 with lushly foliate terminals. The couple mounted the sample above the fireplace in the dining room, which Price endowed with a picturesque bowed ceiling (Fig. 9).

Ironwork by Samuel Yellin-who, like Price, studied at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Arts and subsequently taught there-is a more recent interest of the collectors, who have purchased a pair of 1920s wrought-iron gates with dragon’s head finials (see Fig. 7) and an S-curve sample piece of about 1921 with lushly foliate terminals. The couple mounted the sample above the fireplace in the dining room, which Price endowed with a picturesque bowed ceiling (Fig. 9).

As a young man, the husband was captivated by The Champions of the Mississippi: “A Race for the Buckhorns,” Currier and Ives’s gripping 1866 depiction of a steamboat competition by moonlight. Nurtured by Kenneth M. Newman of the Old Print Shop, the couple made their first purchases of antiques-maps and Currier and Ives prints.

Having paid off their student loans they began searching for Tiffany glass, which intrigued the husband from the moment he first admired it in a friend’s house in Chicago. Over time the couple acquired more than a dozen pieces by Tiffany Studios, among them several table lamps made between 1905 and 1910, with Poppy, Daffodil, Apple Blossom, and Poinsettia shades and patinated bronze bases of various styles (see Figs. 5, 12). An endearing 7 ½- inch-tall three-panel bronze and glass Iris tea screen (Fig. 8), probably designed by Clara Driscoll, traveled with the New-York Historical Society’s 2007 exhibition A New Light on Tiffany, showcasing Driscoll, head of the Women’s Glass Cutting Department at Tiffany Studios, and her “Tiffany Girls.”

In the dining room, over an oak table by the English architect and designer Thomas Jeckyll, hangs a Daffodil chandelier of about 1905, notable for its use of fractured, or “confetti,” glass (see Fig. 9). Large, irregular chunks of glass called “turtleback tiles” emit a molten glow from a chandelier of about the same date that dangles over the Arthur Romney Green drop-leaf table in the couple’s breakfast room.

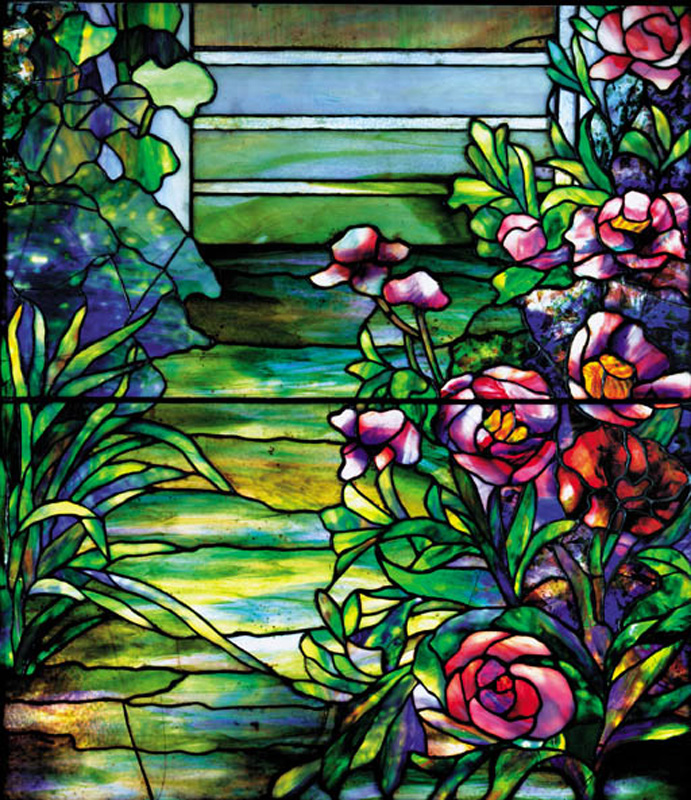

Their first Tiffany window glass, now installed in a powder room, depicts peonies and steps and is a panel from a larger landscape window made about 1908 to 1912 for the Pittsburgh mansion of Richard B. Mellon. Other panels from the window are in the Carnegie and Charles Hosmer Morse museums.

Their first Tiffany window glass, now installed in a powder room, depicts peonies and steps and is a panel from a larger landscape window made about 1908 to 1912 for the Pittsburgh mansion of Richard B. Mellon. Other panels from the window are in the Carnegie and Charles Hosmer Morse museums.

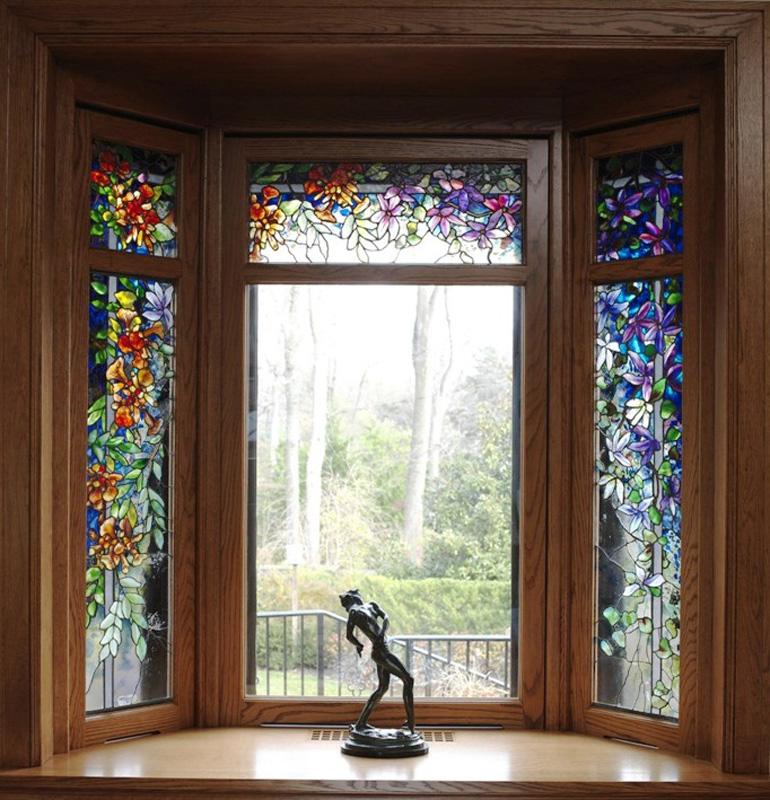

Violet clematis and flame red trumpet vines tumble from the corners of a bay window that the couple installed in their kitchen overlooking a secluded garden (see Fig. 10). From the New Jersey residence of Tiffany manager Joseph Briggs, and possibly made by Briggs himself around 1912, the still life is rendered in mottled, striated, fractured, and textured Favrile glass on a shaded and mottled glass ground. “It is at the highest level of Tiffany’s art, a domestic window incorporating the company’s most popular themes and difficult glass,” the husband says.

Last June the couple acquired a Tiffany Studios window made about 1898 for the Unity Church in Brooklyn (Fig. 11). Irises and lilies frame the landscape view, a classic Resurrection scene memorializing the church’s long-time pastor, the prominent clergyman Stephen H. Camp, who ministered to black troops during the Civil War.

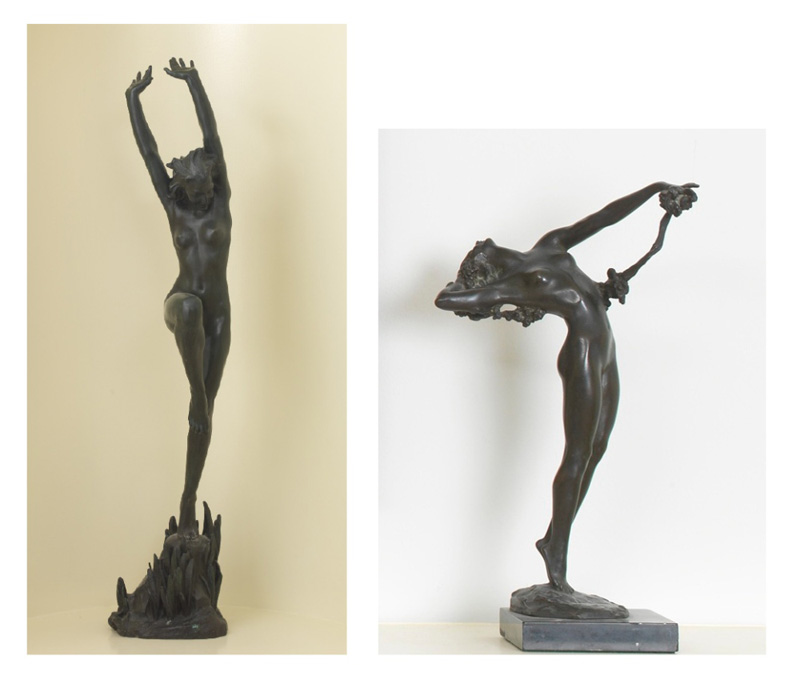

A clutch of wispy chrysanthemums, painted by Louis Comfort Tiffany around 1880, joins many of the couple’s best paintings in the hexagonal master bedroom, which perches atop the porte cochere. On a mantel and in a purpose-built niche nearby are bronzes by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, including Joy of the Waters, one of the artist’s most exuberant nudes, modeled in 1920 (see Figs. 13, 14).

A clutch of wispy chrysanthemums, painted by Louis Comfort Tiffany around 1880, joins many of the couple’s best paintings in the hexagonal master bedroom, which perches atop the porte cochere. On a mantel and in a purpose-built niche nearby are bronzes by Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, including Joy of the Waters, one of the artist’s most exuberant nudes, modeled in 1920 (see Figs. 13, 14).

“I like paintings that I can hear,” the husband says. In 2000, while living in London, the couple invested in a seventeenth-century landscape by Jacob Van Ruisdael (1628/29-1682). Drawn to the Dutch master’s evocative treatment of the natural world, they later found a corollary in nineteenth-century American landscape painting. An autumnal view by John Frederick Kensett entered their collection in 2011 (Fig. 17). Seeking advice from New York dealer Andrew Schoelkopf, they acquired two oil views by William Trost Richards, The Otter Cliffs, a tempestuous Mount Desert, Maine, scene of 1866 (see Fig. 15), and Gentle Surf, New Jersey Coast of 1905. “Richards is a rare artist who is consistently excellent throughout his career. He had the ability to paint motion and volume into the waves. He is the greatest American seascape artist of that moment,” Schoelkopf says.

Large scale, elaborate subject matter, beautiful light, and exceptional depth, Schoelkopf says, distinguish another of the couple’s recent purchases, Alfred Thompson Bricher’s 1877 View on the Providence River (Fig. 16).

Dwight Tryon’s 1913 pastel October depicts a bucolic autumn landscape near the artist’s studio in SouthDartmouth, Massachusetts (Fig. 18). According to Newport paintings dealer William Vareika, it is a quintessential example of tonalism in American art.

The carriage house that Will Price designed for Louis Clarke now houses a 1907 Autocar built at the industrialist’s factory in nearby Ardmore (Fig. 19). It more resembles a motorized carriage or a land cruising yacht than the streamlined transport of today. A work of art, it has gleaming brass lamps and a firewall of polished mahogany veneer.

The carriage house that Will Price designed for Louis Clarke now houses a 1907 Autocar built at the industrialist’s factory in nearby Ardmore (Fig. 19). It more resembles a motorized carriage or a land cruising yacht than the streamlined transport of today. A work of art, it has gleaming brass lamps and a firewall of polished mahogany veneer.

“History gets rewritten through careless restoration. The collectors wanted the work to be correct and the results authentic,” says Walter Higgins, the Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, conservator of antique and classic autos who restored the car. It was bright red when the couple bought it, but after Winterthur conservator Jennifer Mass evaluated the paint Higgins returned it to its original navy blue. An Amish buggy maker replicated the tufted leather upholstery, which is stuffed with horsehair. The car placed first in its class at the Antique Automobile Club of America’s regional fall meet in Hershey, Pennsylvania, last October-a triumph for art, industry, and for this enterprising Pennsylvania couple.

1 For comprehensive discussions of Price’s furniture see Robert Edwards, “William Lightfoot Price: His Furniture and Its Context,” American Furniture 2012, pp. 116-153; and “‘When You Next Look at a Chair’: The Arts and Crafts Furniture of William L. Price,” in George E. Thomas, William L. Price: Arts and Crafts to Modern Design (Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2000), pp. 312-330. 2 Photographs taken c. 1901 show the chair in situ in the main hall of Yorklynne, Price’s house for John O. Gilmore in Merion, Pennsylvania; see Thomas, William L. Price: Arts and Crafts to Modern Design, p. 281.