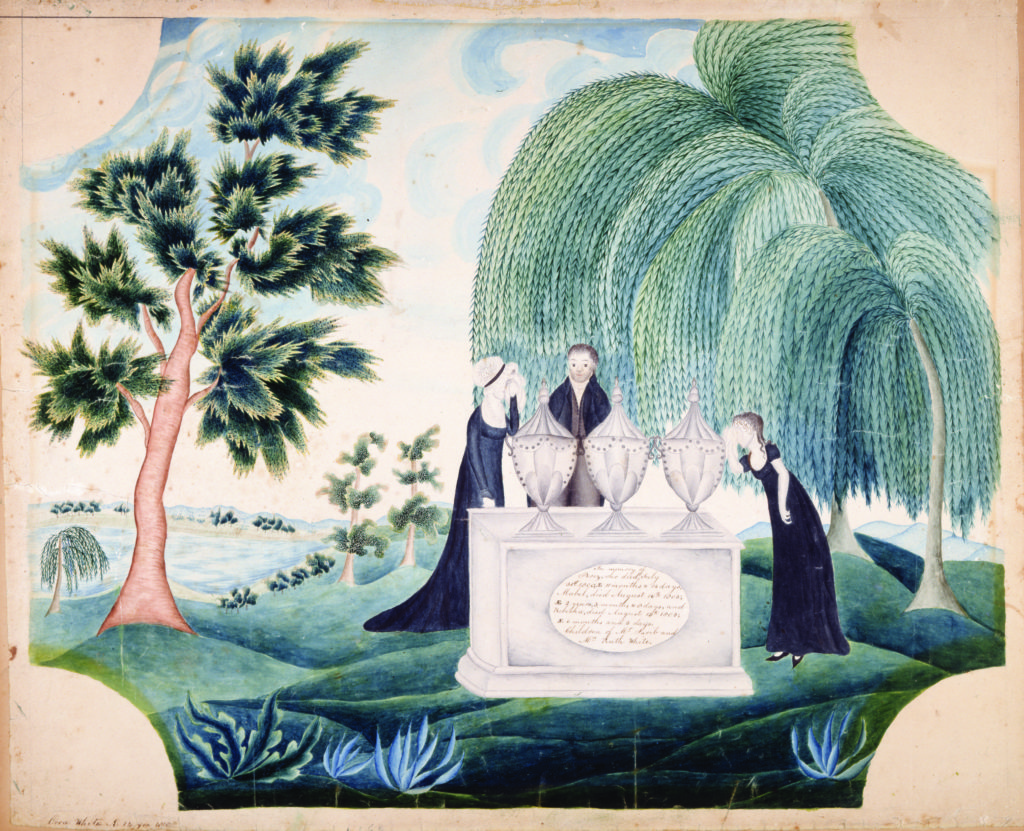

Fig. 3. Mourning piece for Perez, Mabel, and Rebecka White by Orra White (later Hitchcock; 1796–1863), 1810. Watercolor, pen and ink, and pinwork on paper, 18 by 22 1⁄4 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Cyril Irwin Nelson in loving memory of his grandmother Elinor Irwin (Chase) Holden and of his mother, Elise Hastings Macy Nelson; photograph by John Parnell.

The turn of the nineteenth century was a pivotal moment in the natural sciences. Competing theories that explained how the earth was formed as well as newly discovered fossils of strange, extinct animal species challenged a profound belief in Genesis as the literal record of creation. In the United States, an unlikely congress of art, love, religion, and science united in the work of one of America’s first female scientific illustrators. Orra White Hitchcock belongs to a select group of women in Europe and the United States who were uniquely privileged to nourish their own intellectual and artistic inclinations as collaborators with their scientist husbands, even as they performed their expected duties as wives and mothers. Her marriage in 1821 to Edward Hitchcock (1793 –1864), soon to be the first science professor at Amherst College, cemented a years-long partnership based on a bedrock of faith, science, mutual respect, their powers of observation, and a mental capacity for the largest of ideas.

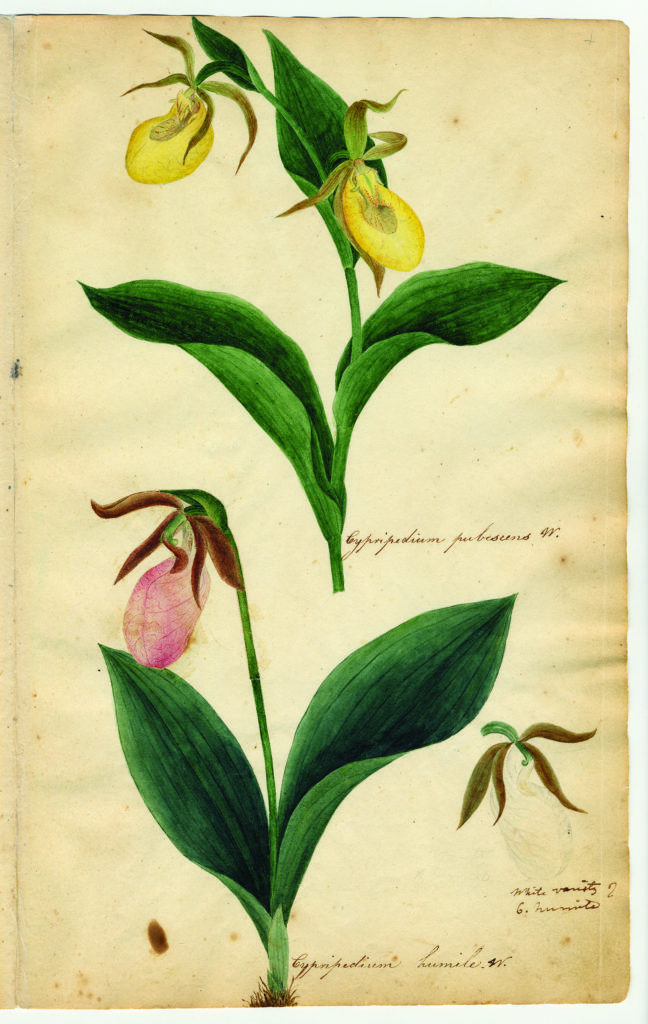

Fig. 4. Page from the unbound album “Herbarium parvum, pictum,” showing Cypripedium pubescens W. (yellow lady’s slipper) andCypripedium humile W. (pink lady’s slipper, moccasin flower), 1817–1821. Watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on paper, 12 7/8 by 7 7/8 inches. Deerfield Academy Archives, Deerfield, Massachusetts.

Orra exhibited an exceptional scientific mind and abundant artistic talent at a young age. Her parents, Jarib White, a wealthy farmer in South Amherst, and Ruth Sherman White, provided their daughter with the best academic opportunities available to either boys or girls in Amherst at the time. As the only surviving daughter of three, she was privileged to receive the same instruction as her brothers and was “fitted . . . for college,” according to the teacher who boarded with the family.1 By 1810 she was a precocious fourteen-year-old student in South Hadley, attending the respected school run by Abby Wright and her half-sister, Sophia Goodrich, as attested by a signed and dated mourning piece White made to commemorate three deceased siblings (Fig. 3). Although the school was renowned for its needlework, the mourning piece was executed in watercolor, a medium White favored throughout her creative life. Her mathematics book testifies to her advanced work in logarithms to predict eclipses and other astronomical phenomena.

White was teaching both art and the exact sciences at Deerfield Academy by age seventeen. It was during this period that she experienced her “hopeful conversion” and professed the deep-seated faith that was to guide her through life. Her quiet religious conviction also wielded a profound influence over the academy’s principal, Edward Hitchcock, a scientific and melancholic young man who experienced his own conversion and fell deeply in love with his erudite colleague.

Fig. 5. Page from “Herbarium parvum, pictum” showing several different grasses, rushes, and sedges, 1817–1821. Watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on paper, 12 7/8 by 7 7/8 inches. Deerfield Academy Archives.

Fig. 6. Page from “Herbarium parvum, pictum” featuring Lythrum verticillatum L. (loosestrife), 1817–1821. Watercolor, graphite, and pen and ink on paper, 12 7/8 by 7 7/8 inches. Deerfield Academy Archives.

Edward’s primary scientific interest was geology, but he devoted the summers between 1816 and 1818 to collecting plants in the Deerfield and Amherst vicinity, with the intention of assembling a herbarium comprising samples of every species native to the region. He was often accompanied by Orra, who documented the plants in ink and watercolor, depicting them as breathing, growing life-forms. She created a visual herbarium of around 175 exquisite watercolors of flowers, grasses, rushes, and sedges, and bound them in an album of sixty-four pages that she titled “Herbarium parvum, pictum”(Figs. 4–6). The album included pages with a single specimen and others with several plants. Each specimen is neatly isolated on the page with its name written beneath or beside it, in a manner similar to the sheets of a physical herbarium. Her attention to veins, stems, anatomy, and color permitted accurate identification of esoteric plants by leading American botanists of the day, with whom Edward corresponded. Orra’s work was thus introduced to Jacob Bigelow (1787–1879), John Torrey (1796–1873), Chester Dewey (1784–1867), and other esteemed scientists who commissioned her to illustrate their articles and publications. During these years, Edward Hitchcock also began a lifelong correspondence and friendship with Yale professor Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864), who in 1818 launched the still-published (under a shorter name) American Journal of Science and the Arts. Edward became a frequent contributor and enlisted Orra to provide maps, scenic views, and illustrations to accompany his articles.

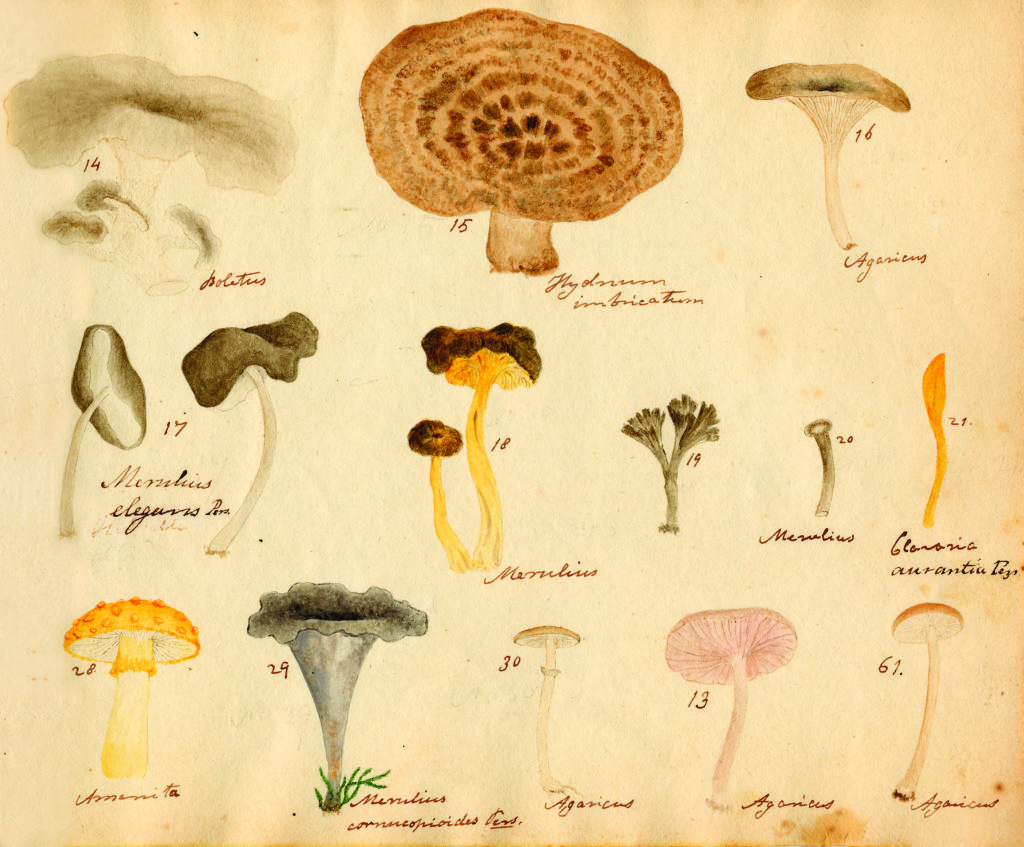

Fig. 7. Page from the album “Fungi selecti picti,” 1821. Watercolor, graphite, pen and ink, and ink wash on paper in sewn album; 6 1⁄2 by 8 1/8 inches. Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, Faculty Biographical Files Collection, gift of Emily Hitchcock Terry.

In 1821, newly married and with Edward recently ordained, the Hitchcocks arrived in Conway, Massachusetts, where Edward took up his duties as Congregationalist pastor. He also embarked on a comprehensive catalogue of the mushrooms growing in and around Conway. The couple’s honeymoon summer was spent foraging, and Orra documented 119 distinct mushrooms and three lichens in an album she titled “Fungi selecti picti.” The twenty illustrated pages are often crowded with multiple specimens capturing color, texture, gills, and other physical characteristics (Fig. 7). During their tenure in Conway, Orra gave birth to a son who died before his second birthday, but despite personal tragedy, she was never derelict in her responsibilities to her husband and his congregation. When they left in 1825 it was afterward remembered, “the influence of Mrs. Hitchcock’s high culture and sincere piety, nowhere obtruded, was everywhere felt.”

We know from Edward Hitchcock’s correspondence with Torrey that Orra made a great number of enlarged botanical drawings in watercolor on sheets of paper that were mounted on fabric, then varnished. Shortly after Hitchcock joined the faculty of Amherst College in 1826 as professor of natural history and chemistry, Orra began to paint charts to provide visual aids for his classroom lectures. More than sixty survive, ranging from letter-size to more than ten feet in height or length. They comprise three major series of watercolor, ink wash, and pen-and-ink drawings on cotton relating to geology, vertebrates, and invertebrates (Figs. 13–16).

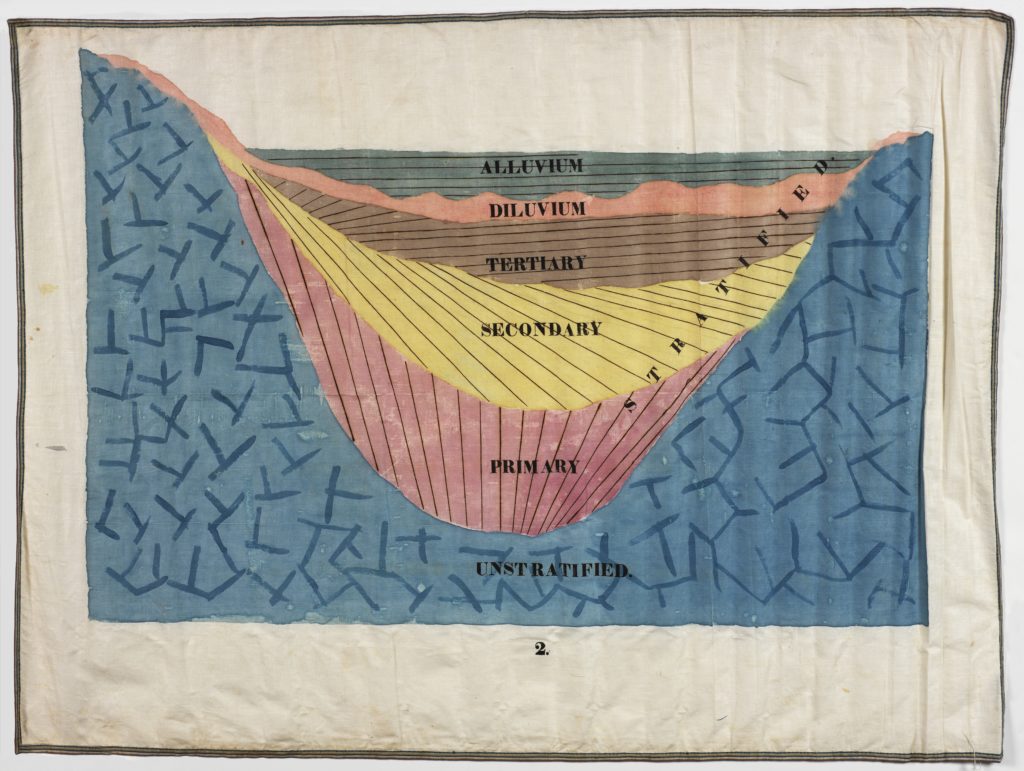

Fig. 8. Stratified deposits, 1828–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor wash on cotton, with woven tape binding, 29 by 40 1/8 inches. Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts, Archives and Special Collections.

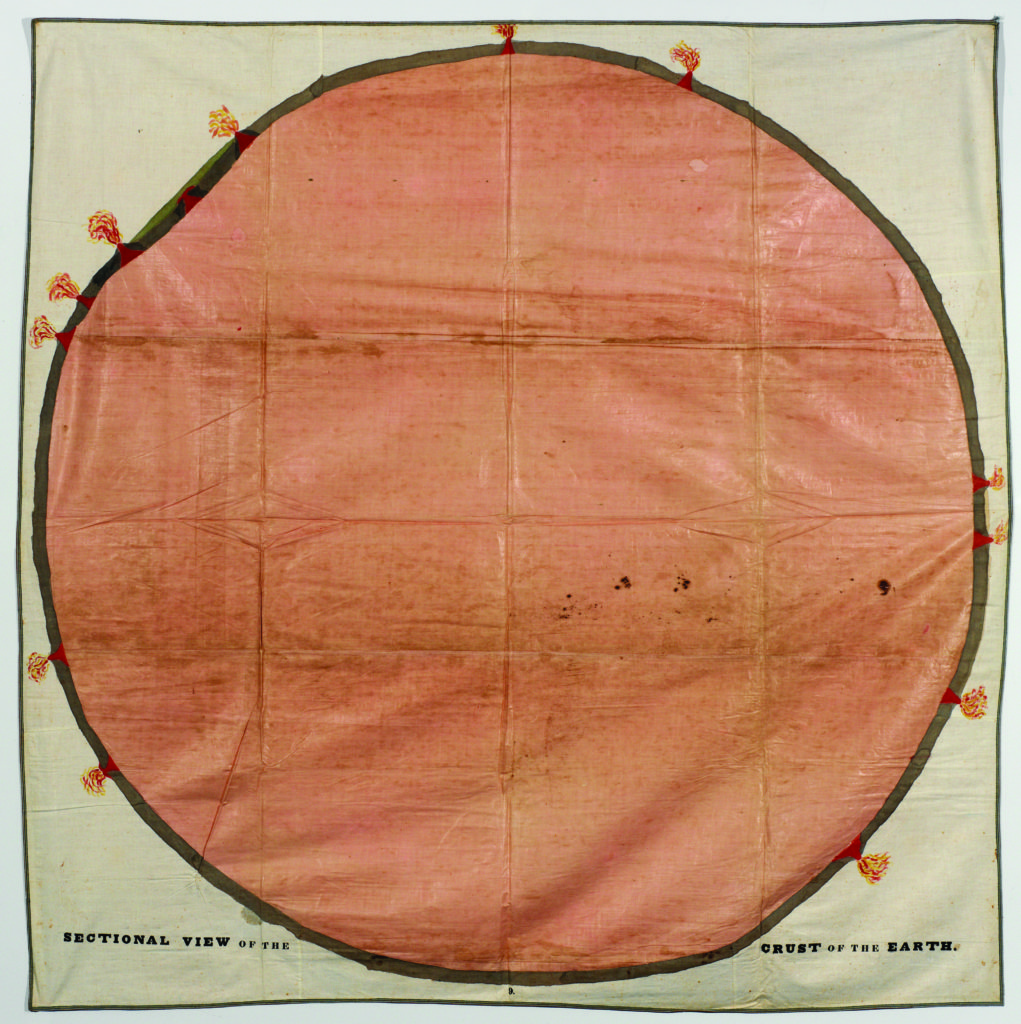

Fig. 9. Sectional View of the Crust of the Earth, 1830–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor on cotton, with woven tape binding, 74 1⁄4 by 75 1⁄2 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

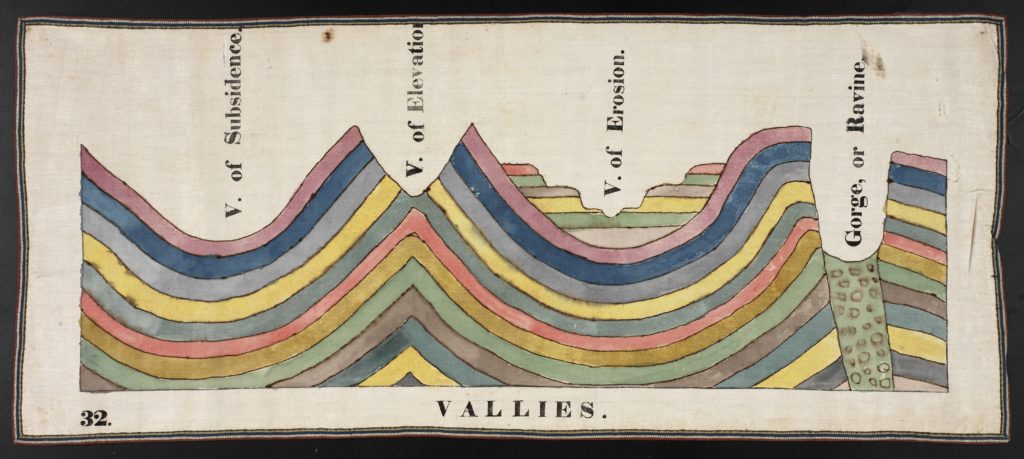

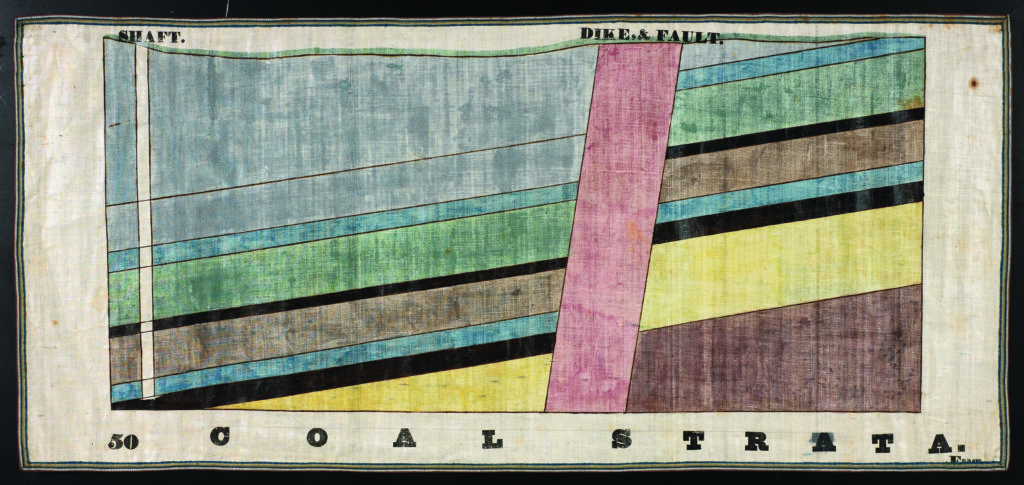

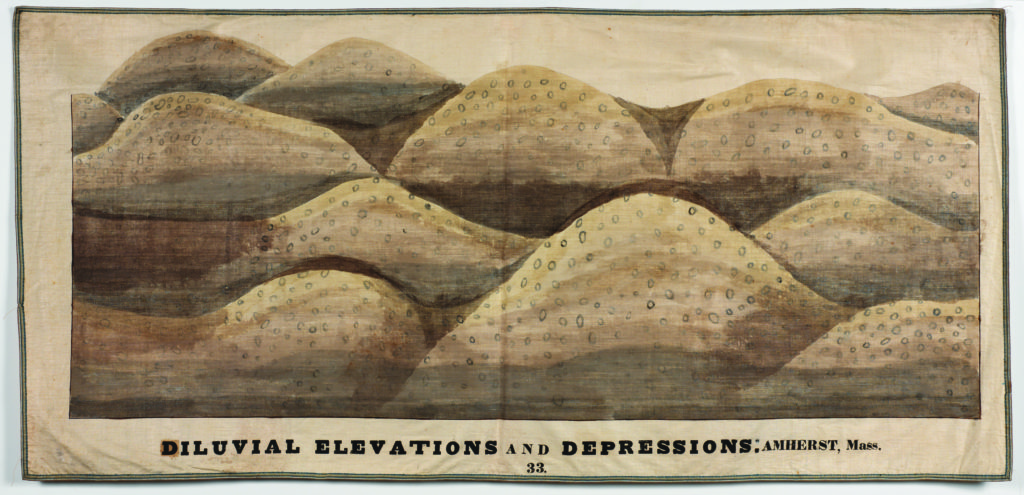

Geologic phenomena form the preponderance of the charts (Figs. 8–12). In 1830 Edward was appointed to conduct a state-sponsored geological survey of Massachusetts, the country’s first. After traversing the state, sometimes accompanied by his wife, in 1833 Hitchcock produced a report of seven hundred pages covering economical geology and topography, and including catalogues of animals and plants, and a descriptive list of rocks and minerals. He acknowledged his indebtedness to “Mrs. Hitchcock” for “nearly all the drawings and maps accompanying every part of this Report. The landscapes are chiefly confined to the Connecticut Valley; it not having been convenient for her to accompany me to distant parts of the state.”2 Her ability to accompany him may have been hampered by her growing family and increasing household duties. She took in boarders; tended gardens, crops, and farm animals; raised two daughters; gave birth to a child who died the same day; and, the year the report was published, gave birth to a third daughter.

Fig. 10. Vallies, 1828–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor wash on cotton, with woven tape binding, 14 3⁄4 by 29 7/8 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Fig. 11. Coal Strata, 1828 –1840. Pen and ink and watercolor wash on cotton, with woven tape binding, 13 1⁄4 by 32 5/8 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Fig. 12. Diluvial Elevations and Depressions: Amherst, Mass., 1828–1840. Ink and watercolor wash on cotton with woven tape binding, 24 7/8 by 48 5/8 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Her comfort with the subject matter, and the wild beauty and spiritual implications of geological formations, seem to have freed the poetry in Orra’s soul. In charting the visible and the invisible—changes that occurred deep within the crust of the earth, as well as on its surface—Orra captured both the force of nature and God’s glory (Fig. 9). In her work, strata, contortions, dikes, veins, faults, and other evidence of upheavals in the landscape were reduced to their essential elements, outlined in black ink, and gorgeously painted in fresh washes of transparent color (Fig. 8). According to her husband, Orra considered these drawings too coarse to merit public acknowledgment. Today they read not only as scientific schematics, but also as presciently modern abstractions. As her husband wrote in the dedication to The Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences (1851), “it is peculiarly appropriate that your name should be associated with mine in any literary effort where the theme is geology, since your artistic skill has done more than my voice to render that science attractive to the young men whom I have instructed.”3

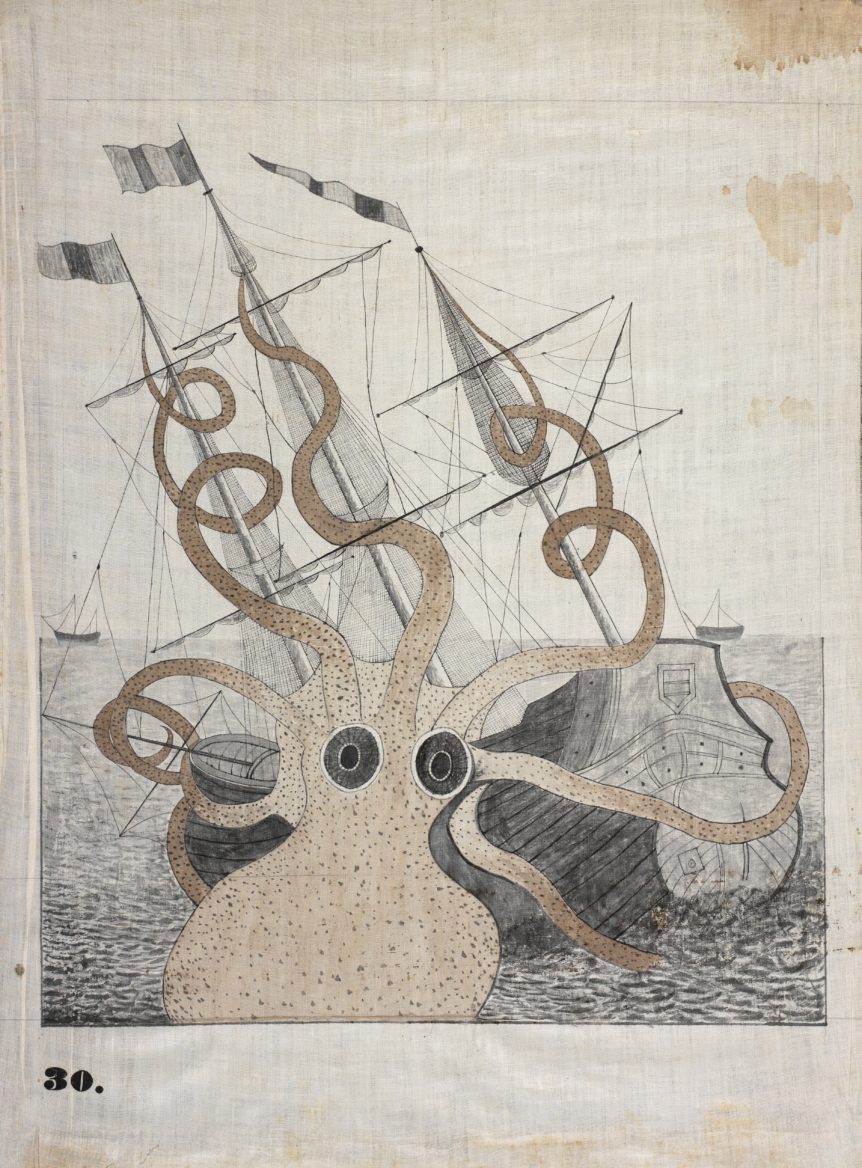

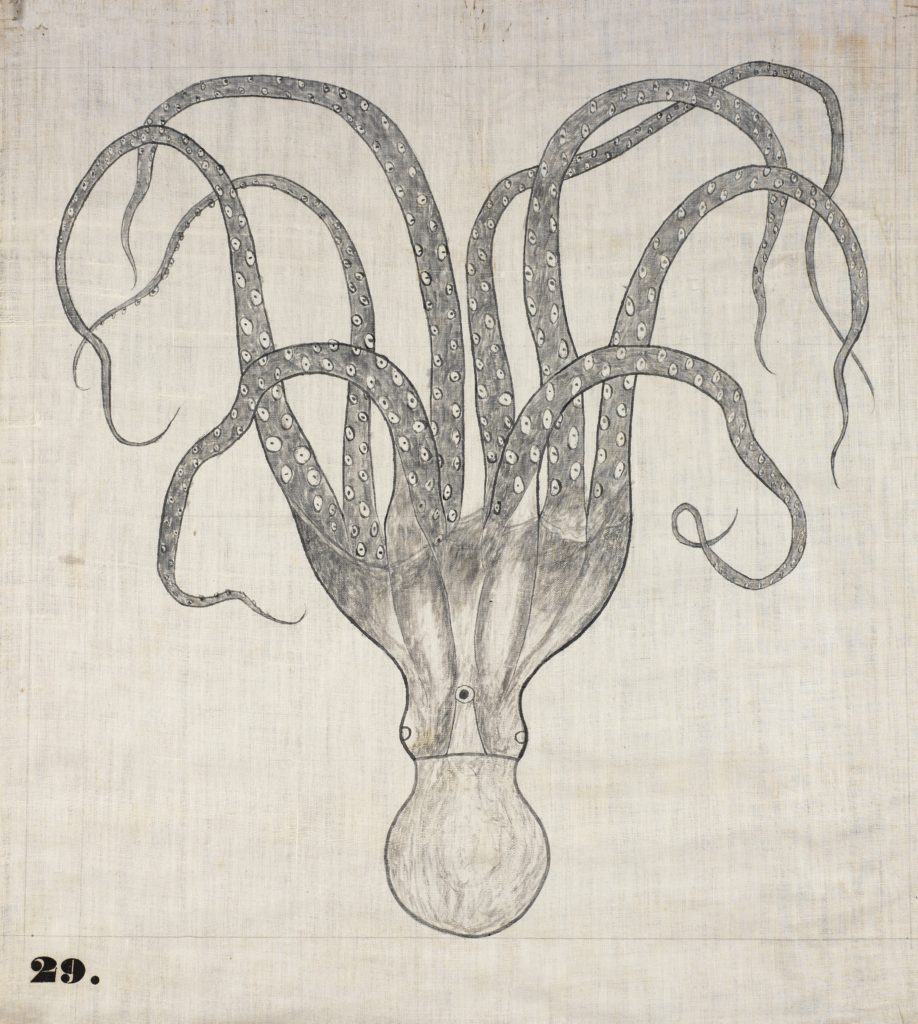

Fig. 13. Octopus, 1828–1840. Pen and ink and ink wash on cotton, 28 3⁄4 by 20 inches.Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

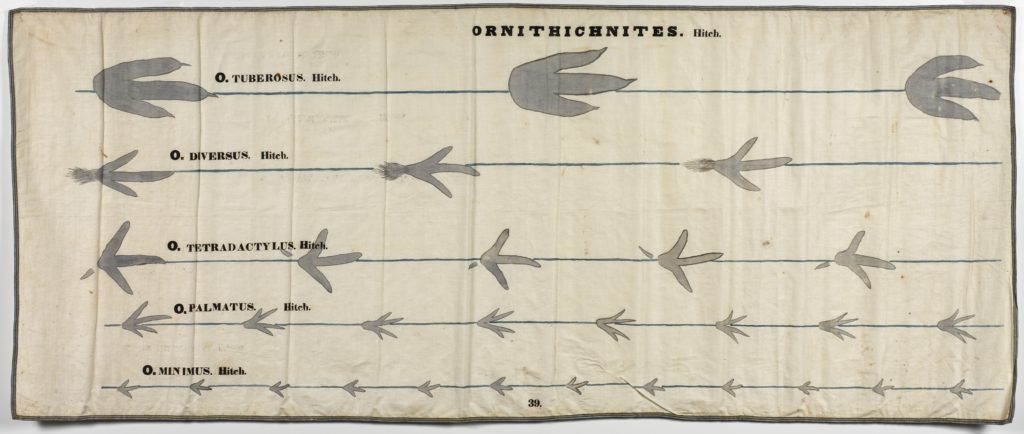

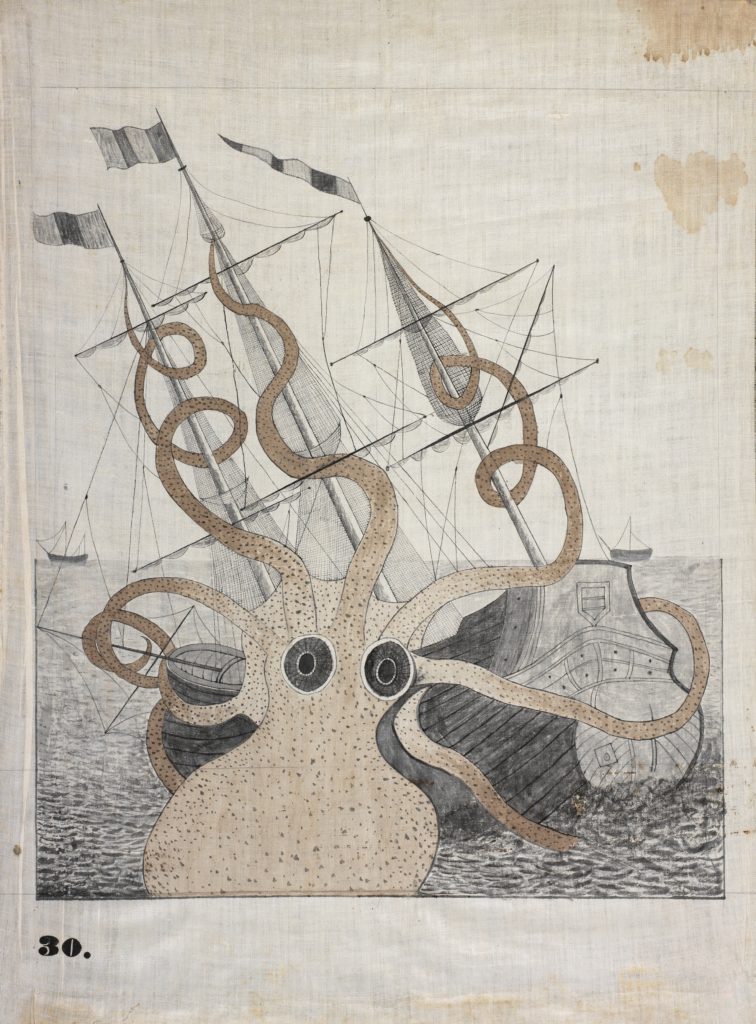

A number of charts illustrate invertebrate fossil remains of extinct or nearly extinct organisms found in geologic strata, including ammonites, trilobites, crinoids, and nummulites. Others include cephalopods, such as the fantastical drawing of an octopus (Fig. 13). Orra based several drawings on engravings in the published work of scientists such as Pierre Denys de Montfort (Fig. 16) and Georges Cuvier, notably the latter’s study of prehistoric species, Recherches sur les ossemens fossils de quadrupèdes. . . . In rendering the charts Ichthyosaurus (Fig. 14) and Plesiosaurus, Orra also paid tribute to another woman in the sciences, Mary Anning (1799–1847), a fossil hunter in Lyme Regis, England, who is credited with being the first to excavate these remains. A smaller group of charts depicts the tracks and footprints of prehistoric creatures that Edward Hitchcock, in 1835, was the first to systematically study, identify, and classify—years before British zoologist Richard Owen coined the word dinosaur in 1842 (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14. Ichthyosaurus, based on an illustration in Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes . . . by Georges Cuvier (1769–1832), 1828–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor wash on cotton, with woven tape binding, 18 3⁄4 by 53 3⁄4 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Fig. 15. Ornithichnites, 1828–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor on cotton, with woven tape binding, 28 1⁄2 by 65 1⁄2 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

In 1855 Orra suffered a devastating fall from a high portico that had no guardrail. She never fully recovered. She died peacefully on May 26, 1863, surrounded by her family, including her six children, after a bout of pneumonia. In the funeral oration delivered on May 28 by past Amherst professor William S. Tyler, he testified to her role as a “true woman” who “lived in, and lived for, her husband and children.” But he also honored her contribution to science through her efforts on behalf of her husband. “At any time, in any place, she would drop everything else, and take up her pencil or her pen to work for him.”

Four months later, her husband published reminiscences of his nearly forty-year association with Amherst College, his accomplishments, and his regrets. On a personal note, he recognized his wife’s contribution in providing artful charts that brought his lessons to life in his many publications. Her role in maintaining the equanimity of her depressive and hypochondriacal husband was widely recognized and acknowledged. As one anonymous author commented after Edward Hitchcock’s death in 1864: “The barest outline of his life cannot be sketched without alluding to the strange, reverent, more than husbandly love with which he regarded his wife, the lively, accomplished and Christian lady, whose life seemed so perfectly fitted into his, the devoted companion of his long pilgrimages, the effectual coworker in his scientific schemes, the perfect sympathiser [sic] in his discouragements and griefs, who with her cheerful trust supplied his gloomy faithlessness and who at last went peacefully down into the dark valley, and thus taught him how to die.”4

Edward and Orra White Hitchcock occupied a place in the very heart of international scientific inquiry. In the early years of the nineteenth century, when the natural world was a magnificent puzzle waiting to be solved, Edward Hitchcock saw the interconnectedness of scientific evidence and God’s created world, and Orra White Hitchcock made it manifest through her art, so all could comprehend and marvel.

Fig. 16. Colossal octopus based on an illustration by Pierre Denys de Montfort (1766–1820), 1828–1840. Pen and ink and watercolor on cotton, 27 7/8 by 21 inches. Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.

Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863), organized by the American Folk Art Museum in collaboration with the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, is on view at the American Folk Art Museum in New York to October 14.

1 Unless otherwise indicated, the quotations in this article are from Rev. Wm. S. Tyler, DD, A Biographical Sketch of Mrs. Orra White Hitchcock Given at Her Funeral, May 28, 1863 (Springfield, Massachusetts, 1863).

2 Edward Hitchcock. Report on the Geology, Mineralogy, Botany, and Zoology of Massachusetts (Amherst, Massachusetts, 1833), p. 108.

3 Robert L. Herbert and Daria D’Arienzo, Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863): An Amherst Woman of Art and Science (Amherst, Massachusetts: Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, 2011), p. 106.

4 “Biography in memoriam of Edward Hitchcock,” 1864, box 2, folder 11, Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections.