Constructing Identity Along the Great Wagon Road

Organized to celebrate the fifth anniversary of Historic Trappe’s Center for Pennsylvania German Studies, Valley Culture: Constructing Identity Along the Great Wagon Road explores the evolution of Pennsylvania German folk art as settlers moved west.

From the Perkiomen Valley of southeastern Pennsylvania to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, locally distinctive forms of material culture emerged. Drawn from nearly a dozen private and museum collections, the exhibition explores how German settlers transformed artifacts of daily life—including fraktur, painted furniture, boxes, and other artifacts—as they settled along the Great Wagon Road.

Pennsylvania’s natural geography is a series of valleys. Major waterways include the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers to the east and the Susquehanna in the middle of the state. These fertile river valleys and their many tributaries powered the rise of agriculture and industry, playing a major role in Pennsylvania’s cultural and economic development. A network of roads developed between Philadelphia and the backcountry, layered onto trails that were used by the Lenape, Shawnee, Seneca, and Tuscarora for generations. As more European settlers came and settlement progressed, the main road west from Philadelphia became known as the Great Wagon Road and eventually connected Philadelphia to Winchester, Virginia, and all the way to Georgia. Drawn by Pennsylvania’s abundant natural resources and religious tolerance, some 80,000 German speaking immigrants, mostly from the Rhine Valley of southwestern Germany, settled in the area by 1783. They brought with them a rich tradition of folk art, which continued to evolve long after they arrived in Pennsylvania. This exhibition showcases objects from six distinct valleys: the Perkiomen Valley, Tulpehocken Valley, Cocalico Valley, Mahantongo Valley, and Brothers Valley, all in Pennsylvania, plus the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Thanks to generous donations made by supporters of Historic Trappe, the museum published an exhibition catalog featuring 116 pages and nearly 100 color images of the extraordinary paint-decorated loaned for the show. The catalog is available exclusively from Historic Trappe’s museum store and their website.

Valley Culture: Constructing Identity Along the Great Wagon Road is on view through August 17, 2025, at the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies, located in the Dewees Tavern, 301 W. Main St., Trappe, PA.

For more information, visit HistoricTrappe.org

Sometimes the origins of the painted boxes and furniture featured in the exhibition remain unknown, but their design motifs relate to pieces made within the other valleys. A vibrant slide-lid box, covered in decoration on every visible surface, had its designs first laid out and then carefully incised into the wood before being executed in paint. The lid is decorated with curving lines in alternating red, white, and blue colors; the sides feature tulips within two-handled vases and chickens embellished with polka dots.

Despite its extraordinary decoration, this box is the only known period example featuring these motifs. It was first published in the July 1925 issue of The Magazine Antiques in a two-part article on “Pennsylvania Brides Boxes and Dower Chests” by the pioneering scholar Esther Stevens Brazer (1898–1945), an interior decorator, teacher, and author of Early American Decoration (1940). Her legacy inspired the founding of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration in 1946.

The Perkiomen Valley

One of the first stops for German-speaking settlers was the Perkiomen Valley, which runs through central Montgomery County. The Perkiomen Creek stretches for thirty-seven miles and fed by several smaller streams that begin in the higher elevations surrounding the valley. The valley became home to a diverse range of religious faiths, including Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, Brethren, Schwenkfelders, Moravians, and Roman Catholics.

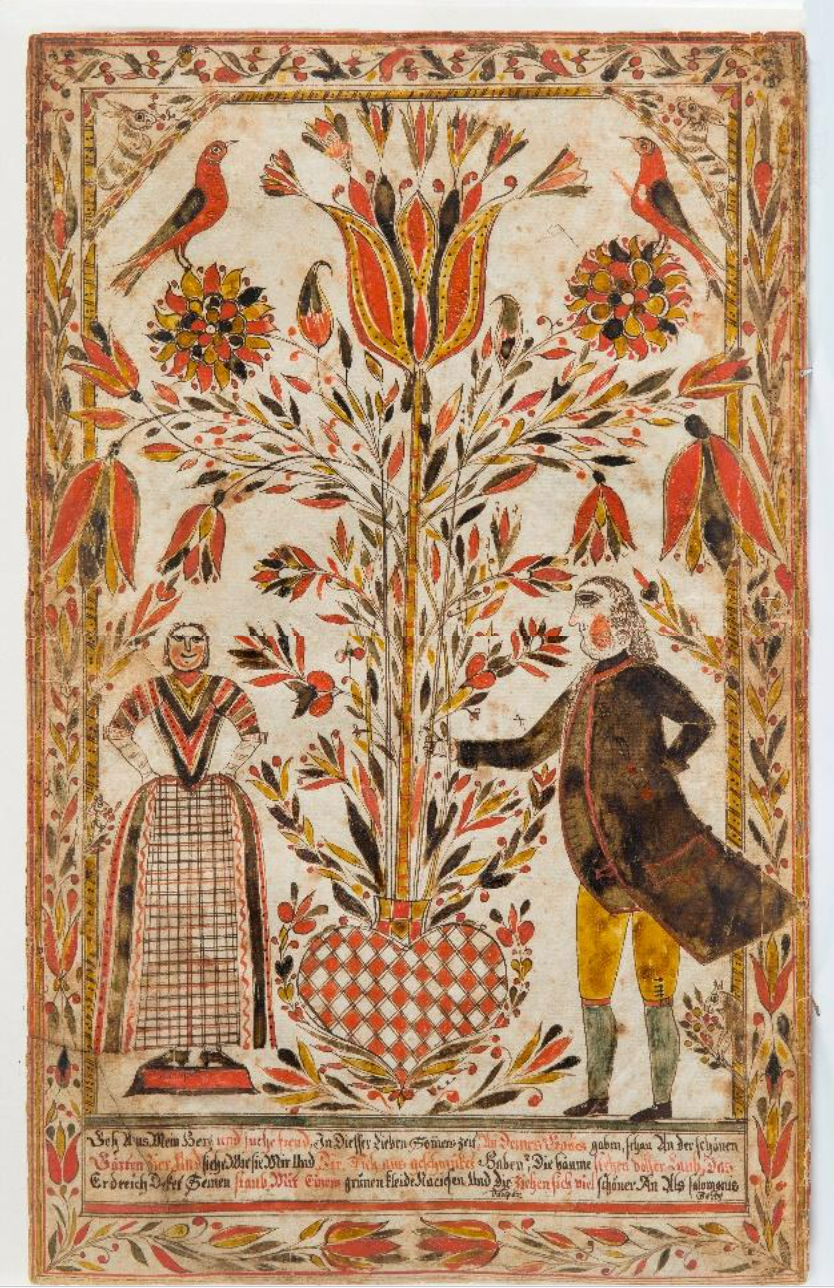

Due to this religious pluralism, a number of decorators and fraktur artists lived in the Perkiomen Valley including Andreas Kolb. This charming fraktur drawing of a couple in colonial garb is attributed to Kolb, who was a highly influential Mennonite fraktur artist and schoolmaster. The woman, who wears a colorful striped gown and checkered apron, resembles the female figures on fraktur by another local artist, Jacob Gottschall. The man wears blue stockings, yellow breeches, and a brown jacket and waistcoat; he grasps the stem of a flower in his right hand and clutches a knife in the left.

This region is home to a large group of chests with blue grounds and white panels with compass stars and floral decoration was made for owners living in northern Montgomery County, near the Berks County border. One of the most impressive examples of the group is a chest with birds perched in large sprays of flowers. It was made for Daniel Eisz in 1795. He was confirmed in 1791 at the Oley Hills Union Church in Berks County, which at that time was an affiliate of the New Hanover parish of Montgomery County. Union churches were common in Pennsylvania and were shared between Lutheran and Reformed congregations. Daniel’s father, Nicholas Ihst (Eis, Eiss), immigrated from Switzerland in 1732. He died in 1804 and was buried at the Boyertown Mennonite Church.

The Tulpehocken Valley

Derived from the Munsee-dialect word Tulpewikaki, meaning “land of turtles,” the Tulpehocken Valley extends across what is now western Berks and eastern Lebanon Counties, bounded by the Blue Ridge and South Mountains and containing approximately 322 square miles. The early Tulpehocken inhabitants were of diverse religious backgrounds. From 1729 to 1743, Lutheran, Reformed, and Moravian factions competed for influence in a period known as the “Tulpehocken Confusion.” The arrival of Lutheran minister Henry Muhlenberg in 1742, followed by Reformed minister Michael Schlatter in 1746, and their efforts to organize churches helped settle this matter.

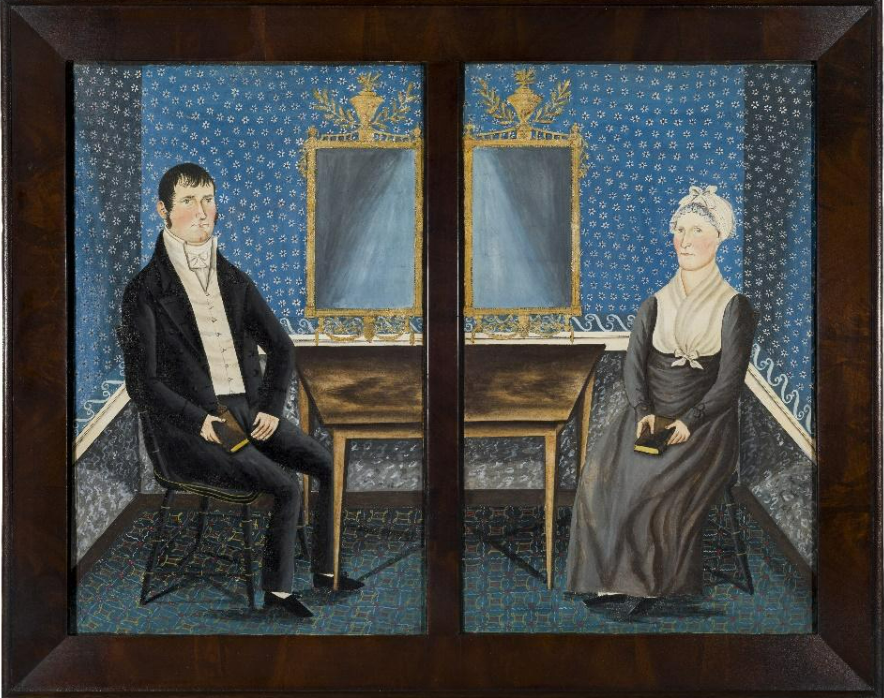

One of the most important portraits to come out of the valley was done by itinerant artist Jacob Maentel. John and Caterina Bickel’s portraits showcase the vibrant interior of their home in Jonestown, Lebanon County, with brilliant blue walls covered in tiny white flowers. John Bickel (1775–1863) was the postmaster of Jonestown for fifty-seven years; he retired in 1859 as the oldest postmaster in the United States. Maentel was a German immigrant who appears to have first settled in Baltimore, where he is listed as a “Portrait Painter” in the 1807 city directory. He soon moved to Pennsylvania and became a prolific artist, first working in simpler profile portraits before attempting frontal compositions and elaborate interiors. Sometime after 1830 he moved west, settling in New Harmony, Indiana.

An extraordinary slide-lid box on view is one of the finest and best-preserved examples of an iconic group of painted furniture from Berks County. The box is decorated on the lid and three sides with tulips, vines, and a large compass star. It is one of seven known examples of slide-lid boxes and miniature chests by this decorator, who also painted full-size chests embellished with black unicorns or horse-and-riders.

The Cocalico Valley

The Cocalico Valley encompasses ten municipalities in northern Lancaster County: the boroughs of Adamstown, Akron, Denver, and Ephrata as well as the townships of East and West Cocalico, Clay, Ephrata, West Earl, and a portion of Earl. The area was first settled by the Lenape and the Susquehannock. The term “Conestoga wagon,” the mode of transportation usually associated with the Great Wagon Road, is likely named after the Conestoga River Valley.

The valley is known for two of the most famous artists whose paint-decorated boxes are highly sought after—the Compass Artist and Jonas Weber. Named for their use of a compass to scribe the outlines for painted decoration, the Compass Artist is known to have decorated dozens of boxes, at least five full-size chests, several small cradles, and a salt box in the early-to-mid 1800s. Several of the boxes have pencil inscriptions of early or original owners who lived in the Cocalico Valley of northern Lancaster County. The most common form is the dome-top box with hinged lid, made in a wide range of sizes. Most of the boxes have a blue ground, which today may appear green due to yellowing varnish, however a smaller number have red grounds. The boxes were decorated with compass work—following the scribed lines—and freehand embellishment. The hardware was simple, consisting of tinned sheet-iron hinges and a hasp decorated with punchwork.

Jonas Weber was born in East Earl Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. By 1838 Jonas lived in Leacock Township, Lancaster County. His father, Abraham Weber, was a miller whose ledger of 1842–52 records the sale of twenty objects made by Jonas Weber for prices ranging from four to thirty cents. Weber’s boxes are typically constructed of pine with tiny wooden pins, hinged lids, and simple tin hasps. This example is built like a miniature chest, including a till compartment on the interior. It is a rare variant with turned feet instead of the typical carved feet seen on the other small chests and boxes illustrated here. Most were painted with bluish-green grounds, but some examples are yellow, green, red, or orange. Many are decorated with flowers, trees, and houses with polychrome details adorning the windows, shutters, front doors, and pitched roofs. The boxes were made in a range of sizes; the smallest ones originally sold for five cents. Weber also made miniature cradles, hanging wall boxes, and carved songbirds.

The Mahantongo Valley

The Mahantongo Valley extends east from the Susquehanna River for seventeen miles; it is bounded to the north by Line Mountain and four miles to the south by the Mahantongo Mountain. Running through parts of Northumberland and Schuylkill Counties, the valley has more than forty waterways, including the Schwaben Creek, Messers Run, and Mahantongo Creek, many of which flow into the Susquehanna. The name “Mahantongo” is a Lenape word that refers to “good hunting grounds.” By the late 1700s, Lutheran and Reformed settlers were moving into the valley, many coming from the Tulpehocken and Cocalico valleys and settlements such as Schaefferstown and Millbach. The valley is known for its distinct furniture painted with a solid ground of either Prussian blue or chrome green (a mixture of Prussian blue and chrome yellow). Chrome yellow did not become commercially available until about 1818 but was swiftly adopted even by rural furniture decorators as a brighter, more stable color than traditional yellow pigments.

Never before exhibited and still owned by the original family for which it was made, a chest of drawers featured in the exhibition is the most elaborate example of Mahantongo Valley furniture known. Although decorated with many features typical of this valley’s painted furniture, in particular the stamped rosettes that march around the frame, the use of so many colors is unusual. Bird and floral motifs are painted on the drawer fronts, as well as praying children and winged angels—both copied from printed fraktur. Unique to this chest of drawers are the female figures painted on the sides. The women’s vibrant checkered dresses are skillfully rendered, using a combination of precise lines and freehand details such as the tulips they hold aloft.

The chest descended in the family of Nathan Knorr and Anna Mayer (1838–1903). Anna’s father John Mayer (1794–1883) was the likely the decorator of much of the furniture to come out of the Mahantongo Valley. Isaac Faust Stiehly (1800–1869) related to the Mayers by marriage, made two cutworks, known as Scherenschnitte (scissor-cuttings) in German, for Anna and John Mayer. Embellished with hand-colored details, they feature a large spread-wing eagle grasping a snake in its beak and talons and flanked by an American flag. Across the bottom, Stiehly included his name and the date; at the top is the recipient’s name and the year each piece was made.

The Brothers Valley

Located in southwestern Pennsylvania, along the Maryland border, the Brothers Valley is geographically part of the Allegheny Mountains and situated in what is now Somerset County. The valley has several waterways, including the Stonycreek River, Buffalo Creek, and Tubs Run, which crisscross its rich soil, interspersed with dense forest, marshy glades, and deep ravines. Before European settlement, it was inhabited by the Haudenosaunee and the Tuscarora, as well as some Lenape and Shawnee peoples. The valley was once part of Bedford County, subdivided in 1771 from Cumberland County after the Mason-Dixon Line was settled in 1769 separating Pennsylvania and Maryland. Somerset County was not established until 1795, when it was carved out of western Bedford County. Brethren families began settling there in the mid- 1700s, followed by thousands of Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, and Amish. These Pennsylvania Germans produced a distinct body of painted boxes with checkerboard decoration as well as vibrant fraktur.

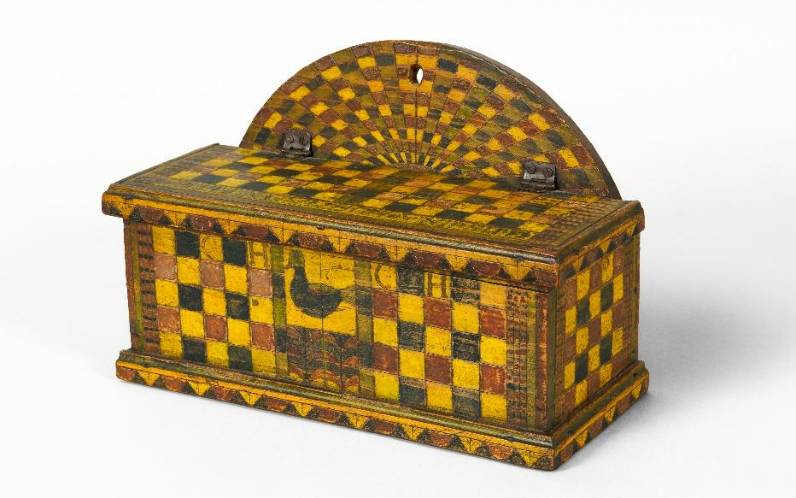

The maker of this noted group of painted boxes and furniture is unknown, but their characteristic checkerboard decoration sets the group apart from others by identifiable Pennsylvania German makers. Additional distinguishing features include the use of deeply incised lines scored into the wood before the paint was applied to create a dazzling array of shapes and color combinations. The designs are abstract in nature, with spiky tulips and other flowers. Inscribed on the lid “Chrisdina x Hoffmann A 1841” and on the front panel “CH CH,” a hanging box made for Christina Hoffmann is the only known example to bear a name or initials. Hoffman is a common surname in Somerset County, making it difficult to identify a specific individual.

The artist also produced a hanging corner cupboard—the only known example of its form within the distinctive group of painted boxes and furniture made in Somerset County (fig 12). The stylized geometric designs and rows of spiky tulips are also seen on smaller boxes within this group. The finials at the top are restored but match the surviving evidence on the cornice. Chip carving at the bottom of the stiles flanking the door is identical to that found on some of the smaller boxes.

The Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley’s rich soil and natural trajectory from north to south made it a perfect place to settle for Germans traveling the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania looking for land, prosperity, and a new place to call home. Many of these settlers were descended from earlier immigrants who had lived for several generations in Pennsylvania; others were new arrivals (usually via the port of Philadelphia) and traveled through the Pennsylvania countryside, passing established farms settled by other German-speaking immigrants, before arriving in the Shenandoah Valley. The valley is defined by the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Allegheny Mountains to the west. The valley is approximately 150 miles long by 25 miles wide and cut by the Massanutten Mountain, which divides the north and south branches of the Shenandoah River. It spans the Virginia counties of Frederick, Clarke, Shenandoah, Warren, Rockingham, Page, Rockbridge, and Augusta as well as Berkeley and Jefferson counties in West Virginia.

Both natives of the predominantly Mennonite settlement in Massanutten, Virginia, Johannes Spitler (1774–1837) and Jacob Strickler (1770–1842) are two of the Shenandoah Valley’s most famous artists. Primarily a farmer, Spitler also decoratively painted furniture, including multiple chests, two tall case clocks, and a hanging cupboard (fig. 13). The hanging wall cupboard was discovered in a closet in the home of Jesse T. Modisett (1904–1998), a descendant of fraktur artist Jacob Strickler. It is the only known example of this form made by Johannes Spitler. Spitler’s work is immediately recognizable by its use of bold, often abstract designs and strong color palette of blue, red, and white.

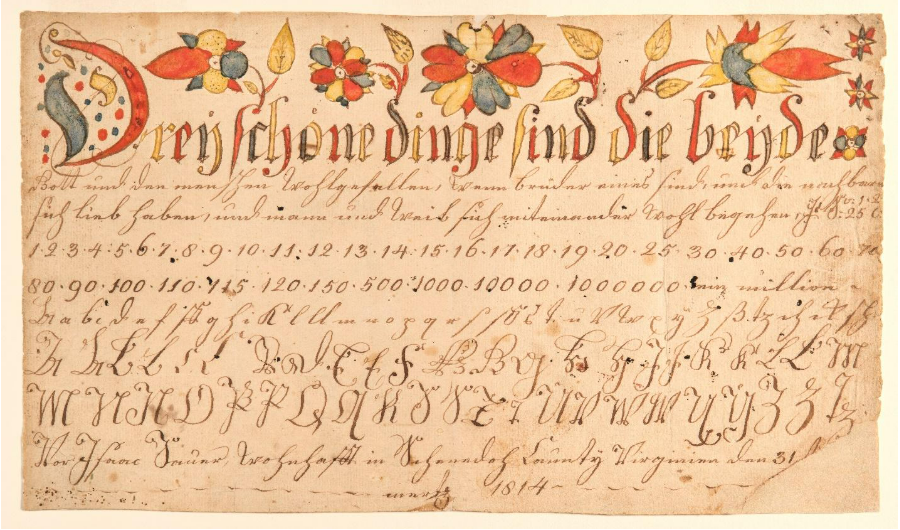

Jacob Strickler was a schoolmaster and fraktur artist who lived near Johannes Spitler. His earliest surviving work is dated 1787; Strickler produced different types of fraktur such as birth records, religious texts, and writing samples. Across the bottom of this Vorschrift, or writing sample, is the inscription (translation): “For Isaac Sauer living in Shenandoah County Virginia the 31st March 1814.” Isaac was the son of Balzer Sour (Sauer) (d. 1821), a Lutheran member of the Hawksbill Church near Luray in Shenandoah (now Page) County. Some of Strickler’s designs bear a striking similarity to those used on Johannes Spitler’s furniture, leading to speculation that the two artists may have collaborated from time to time.