By any standard, the self-taught forty-four-yearold painter Andrew LaMar Hopkins has had a pretty good two-year run. The Wall Street Journal proclaimed him “a rising star” in the art world. The New Orleans Times-Picayune went one better, saying Hopkins was on “a rocket ride to stardom.” When all thirty-eight of his paintings in a solo exhibition were snapped up in three days, Galerie magazine described the sale as “a buying frenzy.” The New York Times published a lengthy profile, and New York magazine, Architectural Digest, Interior Design, Artforum, W, and NPR each trained a spotlight on him in one form or another.

Hopkins’s elegant faux-naïf renderings of Creole life in nineteenth-century New Orleans have been the impetus for this sudden leap to prominence. Only a few years ago, his paintings fetched three hundred dollars apiece. Now they routinely command ten to twenty thousand. Last year, one painting sold for sixty thousand dollars. To top it off, the National Gallery of Art announced last year that it had accepted one of Hopkins’s portraits for its permanent collection.

What’s going on here?

Broadly speaking, while making a name for himself as an artist, Hopkins has single-handedly breathed new life into an all-but-forgotten corner of American art and culture—that of the free Creoles of color in antebellum New Orleans and its environs. “That’s my niche,” Hopkins says, adding with a smile: “Not a lot of artists are working in it right now.”

As to the precise definition of the term “Creole,” there has always been some confusion, which is understandable, since the meaning has changed over time. Essentially, Creole can be said to include any Black, white, or mixed-race person whose lineage traces back to French-colonial Louisiana. While doing research for his Creole paintings, in fact, Hopkins, who was born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1977, discovered that he himself is Creole. He was able to trace his lineage back to a Frenchman named Nicolas Baudin, who received a Louisiana land grant in 1710.

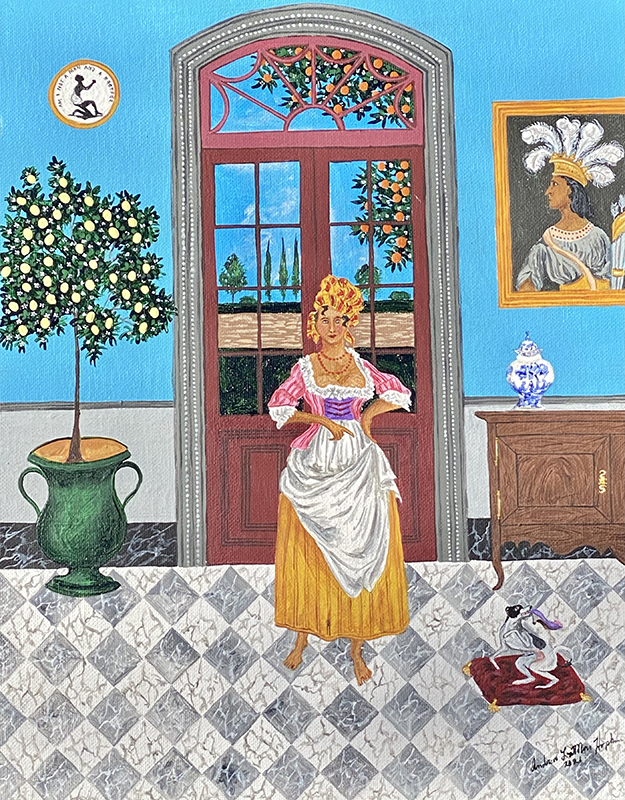

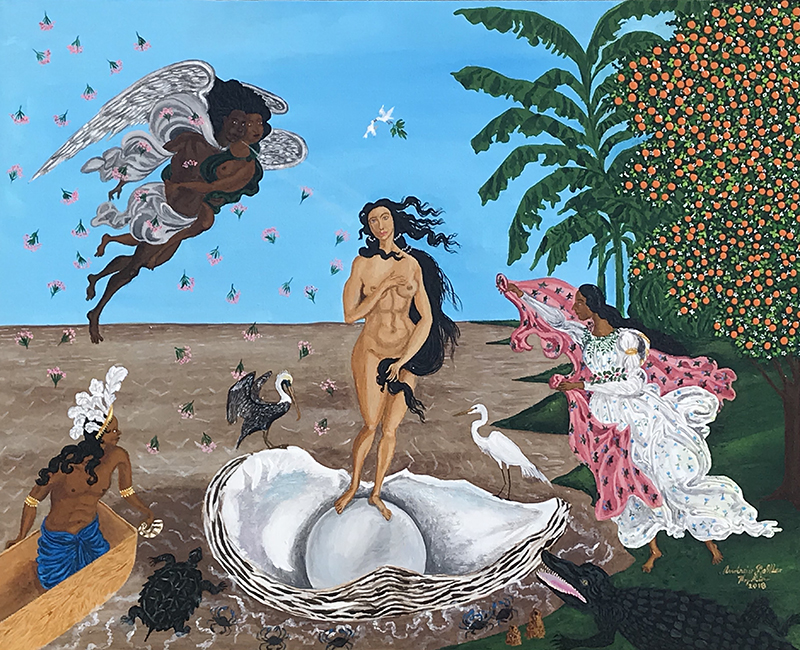

Hopkins’s Creole paintings depict a sunny Utopia of ease and refinement. Top hats and cutaways are typical garb for his somewhat dandified gentlemen, exquisite robes and gowns for the ladies. Rain clouds never darken his skies. He gives his pictures aptly idyllic titles: Tea and Light Refreshments at the Creole Habitation, Creole Elegance, Creole Love, Off to the Opera, A Beautiful Day in Faubourg Tremé. Hopkins’s style is appealingly simple, yet at the same time sophisticated and knowing, quite unlike that of Grandma Moses, with whom he is often compared. The difference is between her genuine na f and his faux. Hopkins mixes perspectives with ease. For example, as he does in Creole Love, he tends to drop flat, two-dimensional ground treatments (carpets, floorboards, or pavements) into three-dimensional landscapes.

His imagination and sense of humor, too, come into play, of course, but his departures from strict reality are tempered by a faithful representation of architectural details, interior decor, furniture, fashions, and even the vegetation seen in his paintings. They are all rigorously accurate down to the last window trim or turban, which is a result of his passion for antiques and history from the age of nine. While other children were playing outdoors, Hopkins spent his hours in the library reading about such things as cameo necklaces, cherrywood hunt tables, and mahogany overmantels. “The past is my happy place,” he says.

As a child, before he started painting, Hopkins made miniature pieces of period furniture out of clay. As a teenager he volunteered to work at the Old Ursuline Convent Museum in New Orleans, and after college he led tours at Laura Plantation, which is officially designated as a Louisiana Creole Heritage Site. By the time he was twenty-two, his expertise in Creole culture was well established. He opened an antiques shop and was hired as assistant manager of the gift shop at the 1850 House museum in one of Jackson Square’s Pontalba buildings. The museum is furnished as an accurate representation of an affluent mid-nineteenth-century dwelling.

In his mind’s eye, Andrew Hopkins’s happy place is not based solely on inanimate antiques. There are people in it too, many of them famous characters who once inhabited Creole Louisiana, and they appear in his paintings— people like Marie Laveau, the voodoo queen who cast spells in her French Quarter cottage; Gabriel Aime, a sugar planter and owner of Le Petite Versailles, a mansion equal in opulence to its better-known neighbor, Oak Alley; and John James Audubon, the great ornithologist and painter, who is celebrated for his encyclopedic Birds of America. Audubon was the illegitimate son of a French sea captain and a Creole servant. Hopkins shows Audubon lounging in the salon of his house in the French Quarter where three of his paintings, including the famous pink flamingo, hang on the wall.

Of all Hopkins’s paintings, however, the ones that have created the greatest buzz are his self-portraits in which he is dressed in drag as his 1950s-style alter ego, Désirée Joséphine Duplantier, a chic Creole lady. Désirée has an extensive wardrobe of modish fifties apparel, based on gowns, dresses, suits, and hats by Dior, Givenchy, Chanel, Balenciaga and others. Especially notable are the hats, which were a primary means of stylistic expression in that period and include such confections as the cloche, toque, pill box, mushroom, halo, fascinator, vagabond, cartwheel, and peach bucket. Hopkins has no qualms about appearing in public in full drag as Désirée, and he does so frequently at book signings, press appearances, openings, large parties, and intimate gatherings. At six-foot-two, and taller in stiletto heels, there is clearly an element of self-mocking humor underpinning the pose.

“I’ve always been who I am,” he says. His elementary school, Hopkins says, had thematic play areas, equipped with wardrobes of costumes, where students could follow their impulses and give their imaginations free rein. “I would always choose House rather than Fire Station or Music Hall, and I would put on women’s clothes,” he says. “I was never criticized or made fun of for doing that, and I’ve never felt I was doing anything wrong or out of place.”

Hopkins has extended his renown considerably through Instagram (@boyneworleans1850), adding video, voice, and music to the social media mix. His Instagram posts are expertly curated, informative, highly entertaining, and often downright hilarious.

So it has indeed been a fruitful two years for Andrew LaMar Hopkins. Quite apart from his financial and critical success as an artist, he has blithely blown past the traditional racial, sexual, and gender constraints that have ruled the binary features of our Western culture with an iron fist, until now.

JOHN BERENDT is the author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.