I’ll never tell,” replied Frankie Welch in her soft southern drawl whenever asked her political party affiliation. Such diplomacy combined with a gracious demeanor made her dress shop, Frankie Welch of Virginia, a favorite among the elite in Washington, DC, for decades. She offered coordinated wardrobes suited for women in the public eye as well as confidential advice about what cuts and colors best flattered them. Welch established a network that led to White House commissions, extensive media attention, and a career as a preeminent designer of custom scarves.

Born Mary Frances Barnett in Rome, Georgia, in 1924, Welch demonstrated a passion for fabrics and fashion from a young age. At Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, she majored in clothing and design, started a small business helping the “rich girls” with their ball dresses, modeled at a local department store, and proved to be a popular student. She married her childhood sweetheart, William Welch, in 1944, and they moved to Madison, Wisconsin, in 1950, where Bill pursued a master’s degree, and Frankie both took and taught sewing classes.

In 1952 they moved to Alexandria, Virginia, for Bill’s work, first with the C.I.A., then as a congressional aide, and finally with the Veterans Administration. Frankie balanced motherhood—her first daughter was born in Wisconsin and her second in Virginia—with a desire to work. She taught a variety of “fashion know-how” and sewing classes, as well as high school home economics. She built a reputation as knowledgeable about fashion and discreet in her guidance, and by the early 1960s she took on the role of private fashion consultant. She once told Women’s Wear Daily, “There’s something about a woman earning her own money that gives her an identity. . . . I feel I’m contributing. By making a woman look beautiful. It’s so rewarding.”

Welch opened her eponymous store in 1963 in a historic building in Old Town Alexandria, and she and her family lived on the upper floors during its early years. In addition to clothes by primarily American designers in a middle price range, she offered some garments of her own design, most notably her “Frankie” dress. This popular and versatile hostess dress with its paper-doll-like pattern could be tied multiple ways—in the front or back, with a high waist or natural waist—and made in innumerable materials and trims. Many prominent women donned Frankies, including reporter Wauhillau LaHay when she became president of the Washington Press Club and Native American rights activist LaDonna Harris when she was recognized as a Woman of the Year at a televised Kennedy Center event; journalist Frances Cawthon in Atlanta once mused that the Frankie was “the one dress” that had been to more White House dinners than any other.

Welch created her first scarf design in 1967 after one of her customers, Virginia Rusk, wife of Secretary of State Dean Rusk, asked her to design something “truly American” for the Johnson White House and State Department to use as gifts. Aware of the current vogue for signature scarves and inspired by a trip to her hometown, she devised the “Cherokee Alphabet” scarf, translating the iconic Sequoyah syllabary into a dynamic fashion accessory. Though the design raises issues of cultural appropriation today, Welch viewed it as representing her country, her state (which was home to many Cherokee before their forced removal), and her family (which she believed to be part Cherokee, based on oral family tradition). This scarf design—the first of thousands—remained her most popular throughout her career.

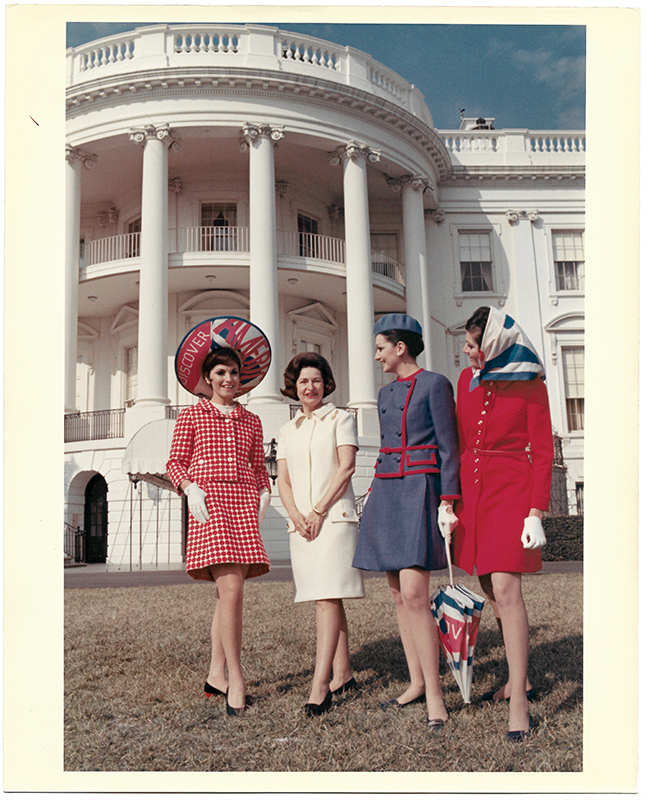

Welch’s second scarf debuted early the following year, 1968, at a fashion show at the White House hosted by Lady Bird Johnson. The emphatically patriotic affair promoted the American fashion industry, and, through its theme “How to Discover America in Style,” connected to Mrs. Johnson’s interests in roadside and urban beautification and President Lyndon Johnson’s efforts to encourage domestic vacation travel. Welch’s scarf, a red, white, and blue abstraction of the continental United States with the words “Discover America,” was worn by models and given as gifts to the governors’ wives in attendance.

The day after the White House fashion show, Welch’s friend Betty Ford, whose husband was House minority leader at the time, asked her to design “something fresh, a new approach” for the Republicans. She settled on the theme of “fresh as a daisy” and created a floral pattern that subtly incorporates the words “Republican National Convention,” “Miami, Florida,” and “August 7, 1968.” Welch referred to it as a “documentary fabric,” and it joined a long tradition in the United States of commemorative textiles, through which Americans have displayed their patriotism, announced their political allegiances, and participated in and recorded historical events. The material debuted at a fashion show for Republican women in Washington in May, and fifty hostesses wore dresses made with the fabric to the opening luncheon of the Republican National Convention in August.

That political season, Welch also designed scarves and dresses for Hubert Humphrey’s presidential campaign members and Richard Nixon’s inauguration attendees. Her emerald green and sapphire blue “H-Line” dresses for Humphrey, with their large Hs on the front and back, were particularly successful, earning praise for being easily visible—even from a distance—on television. They also found admirers among her customers who were not Humphrey supporters, including Betty Ford, who tried one on while selecting clothes to wear to the Republican convention, thinking it was “really pretty,” but politely said, “I don’t think I’ll take it after all,” when she learned it was for a Democrat.

Following this quick succession of high-profile fashion accomplishments, Welch formalized her scarf business and expanded beyond political commissions to create thousands of custom scarf designs for institutions, schools, individuals, conventions, businesses, and special events over the next few decades. Welch was outgoing and enjoyed engaging with clients and promoting her couture. She often drew a design informally while talking with a client so that they could discuss it immediately. She believed that it was important “to study the organization and find out what makes it tick to come up with a design that really signifies them.” She created scarves for the Smithsonian Institution, the Princeton Club in New York, the Red Cross, McDonald’s, the National Press Club, the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, numerous political candidates, the US Naval Academy, the World Bank, the Washington Star, the American Association of University Women, and the Delta Sigma Theta sorority founded at Howard University, among many others.

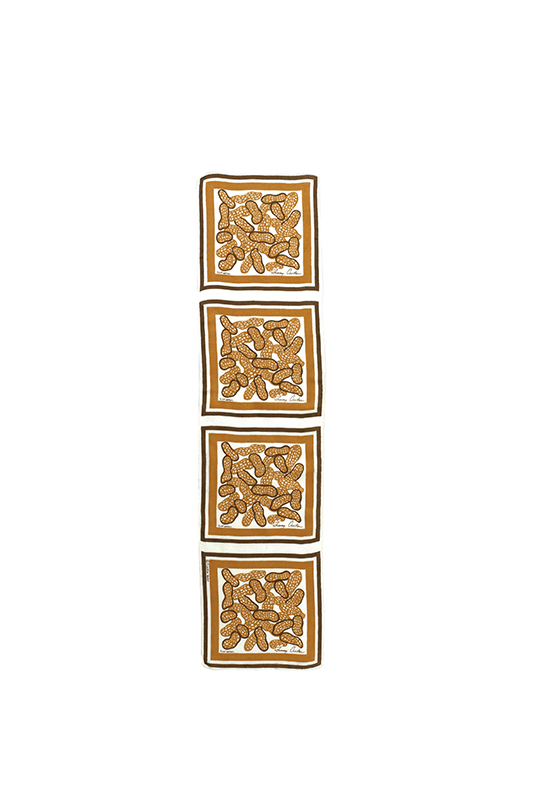

Welch’s earliest scarves typically were large squares of cotton or silk, frequently including text as a design element. By the early 1970s she began using a standard of eight-by-eight-inch pattern segments in her scarves, which were often made of the popular synthetic fabrics of the era. Most scarves comprised four segments in a column, though she sometimes printed yardage of the patterned material to use for making Frankie dresses, and hemmed single segments into squares she called “napachiefs,” a portmanteau term combining “napkin” and “handkerchief.” Stylistically, toward the late 1970s, her new scarves shifted from an emphasis on logos and typography to small floral elements and architectural details. Welch followed the segmented pattern format for more than a decade, then returned, in the mid-1980s, to large square scarves, often of silk and influenced by the French luxury brand Hermès.

Welch received much recognition for her accomplishments in fashion and scarf design. She was especially honored when Betty Ford selected a dress by her to donate to the First Ladies Collection at the Smithsonian Institution in 1976. The Textile Museum in Washington, DC, held the first major exhibition of Welch’s work in 1980, and that was followed by many more shows, including one at the Athenaeum in Alexandria. Interest in her work continues, and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum recently added a group of her scarves to its collection. Frankie Welch closed her shop in 1990 and stopped designing scarves at the turn of the century. Beginning to experience dementia, she retired to Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2001 to be near one of her daughters, and she passed away in 2021. Welch was a remarkably successful entrepreneur who defined her own career in fashion in the midst of Washington’s constantly shifting and often fraught political scene— carefully adhering to a nonpartisan path. She believed that “scarves are forever,” and she leaves behind a vibrant body of work, a fabric chronology of American life.

The monograph Frankie Welch’s Americana: Fashion, Scarves, and Politics, written by Ashley Callahan with a foreword by LaDonna Harris, was recently published by the University of Georgia Press in association with Georgia Humanities. An exhibition of the same title is on view at the University of Georgia’s Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Gallery through July 8.