Chaim Gross

The sculptor Chaim Gross (1902–1991) was a master of the direct carving technique—in which preparatory clay models are dispensed with and an artist creates in a rush of inspiration as he works a piece of wood or stone. Gross’s preferred materials were hardwoods such as mahogany, ebony, and cocobolo, and his studio on the ground floor of a town house in New York’s Greenwich Village—a place we visited in the September/October 2016 issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES—is a woodworker’s paradise. The sculpture Gross was working on when he died is still clamped in a vise on the front of his worktable.

Daniel Chester French

Best known as the maker of the monumental sculpture that sits in the Lincoln Memorial, Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) built a spacious studio in 1898 on the grounds of Chesterwood, his summer residence in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. His unfinished Andromeda sits atop a turntable mounted on a wheeled platform that could be moved outdoors along rail tracks, should French wish to work on his sculptures en plein air.

N. C. Wyeth

With proceeds from his work illustrating Treasure Island in 1911, Newell Convers Wyeth (1882–1945) purchased eighteen acres in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where he built a house and studio. The impressive studio has a massive Palladian window and is furnished with books, costumes, and an array of objects—such as a canoe and a tricorn hat that adorns a bust of George Washington—that the artist used as inspiration and models for his work. In 1923, Wyeth tacked on an addition for mural painting that features a floor-to-ceiling greenhouse window and a double-decker ladder to help him create his largest compositions.

Thomas Cole

The cradle of the Hudson River school of art is this small room in a storehouse on the grounds of Cedar Grove, a one-time farm and now museum in the village of Catskill, New York. There, at the feet of the village’s namesake mountains on a hilltop above the river, is where artist Thomas Cole (1801–1848), the school’s founding spirit, began to work a few years after making Cedar Grove his home in 1836. The space is known as the Old Studio. Cole built himself a commodious Italianate studio in 1846, two years before his untimely death. Later demolished, the New Studio was reconstructed in 2016 and is now used for museum exhibitions and events.

Andrew Wyeth

Shortly after his marriage to Betsy James in 1940, Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) moved into a converted 1875 schoolhouse just down the road from his childhood home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Even after the couple bought another home nearby, the painter maintained his studio here until his death. The austerity of the space makes an intriguing counterpoint to the expansive neighboring studio that his father worked in, which is also now on the campus of the Brandywine River Museum of Art. The painting and the sketches (reproductions, in this case) mount-ed on the walls of the younger Wyeth’s studio demonstrate how the artist studied his subjects before producing finished works, which he was in the habit of displaying for family and friends in the kitchen. Lined up in jelly jars are rows of pigment powders, including jewel-like tones of blue and red. An egg carton references the tempera medium he favored.

Charles M. Russell

Known as the “Cowboy Artist,” Charles M. Russell (1864–1926) was sent by his prosperous family in St. Louis to work on a Montana ranch at age sixteen—a move his parents hoped would quell the boy’s notional passion for the Old West. The ploy did not work. Over the next decade, Russell, who had always drawn and painted as a boy, worked variously as a sheepherder, hunter, horse wrangler, and cattle hand. In the late 1880s he lived for a time among members of the Black-feet nation, and later was a devoted advocate for Native American rights. Russell’s watercolors of western life gained enough attention in Montana that he became a full-time artist in 1892, executing paintings for clients such as saloon-keepers. Nancy Cooper, whom Russell married in 1896, was responsible for promoting him nationwide. In 1903, to memorialize his youth, Russell built a log cabin as a studio on the grounds of their tidy, gabled house in Great Falls, Montana, and furnished it with artifacts redolent of his early days on the range.

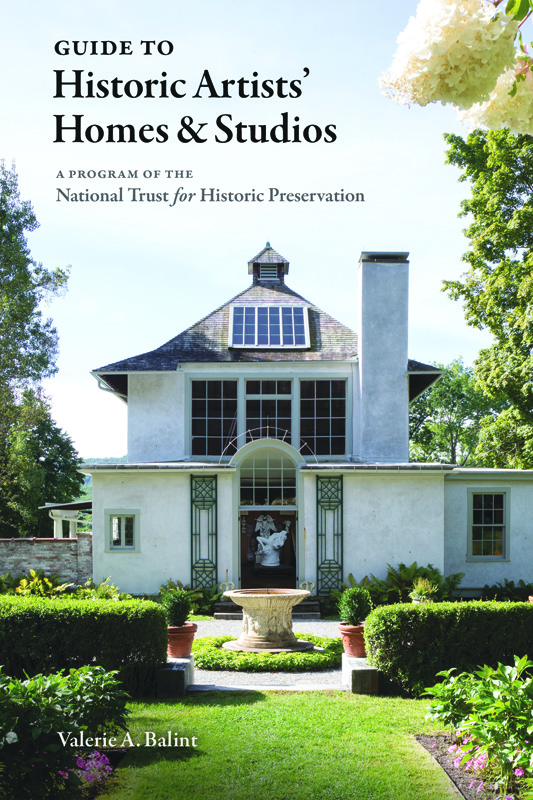

Gari Melchers

Julius Garibaldi Melchers, known as Gari (1860–1932), was an American impressionist born in Detroit and trained in Europe, who was successful and influential in his own lifetime. After his death, he descended into relative obscurity, but has been rediscovered over the last twenty-five years by the art market and the general public. Belmont, his Virginia estate, represents the sixteen-year effort he and his wife, Corinne, invested in creating both a convivial retreat to nurture artistic production and an environment that embodies southern hospitality and a bucolic lifestyle. The showcase of the estate is Melchers’s massive granite and sandstone studio, which he designed in the 1920s. Today it houses the largest collection of his paintings and drawings anywhere—some sixteen hundred items—and features rotating exhibitions spanning his career. The studio workroom includes his original artist materials, a cabinet likely owned by his sculptor father, also Julius, plaster casts, and floor-to-ceiling paintings.