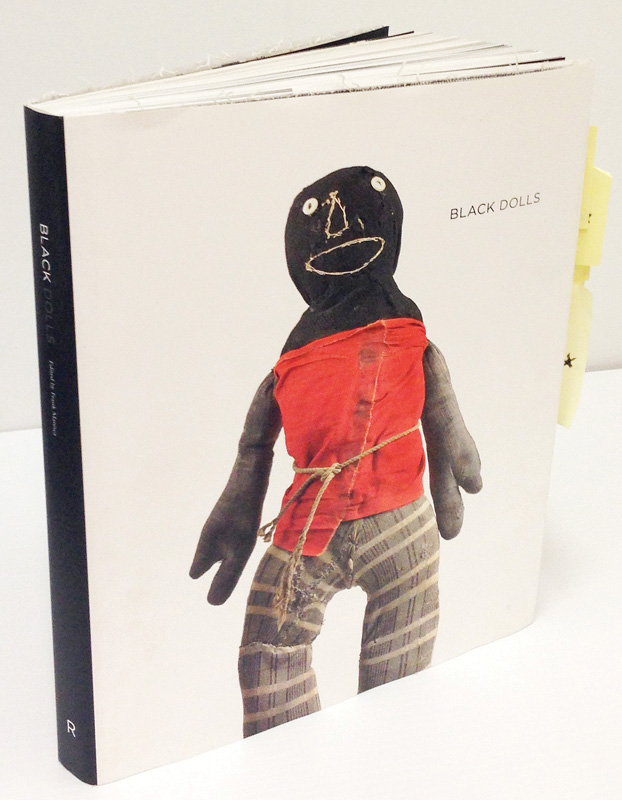

The dolls you see here, rescued from the vast diaspora of their kin by Deborah Neffand bound together in a work of art by Radius Books, will inevitably be admired as sculptural objects and as fine examples of a folk art passed down through generations from roughly 1850 to 1940. They are that to be sure. And yet in their time, as perhaps in ours, they have done and perhaps still can do something more important than stand in vitrines: they give us an unusual part of African-American culture—an art without reference to suffering, oppression, exclusion. Here they are, each one bold, unexpected, beautifully improvised, mute, and glorious. Between the covers of the book, Black Dolls, Margo Jefferson has written of her childhood as a black child with white dolls, and Faith Ringgold of hers as a black child with black dolls, but no one has written the untold histories behind the dolls in these pages. The collector, Deborah Neff, the editor, Frank Maresca, and the photographer, Ellen McDermott, have let them and the vintage photographs that Neff collected to accompany them speak for themselves. In an overly-explained world that is as important a gesture as assembling the collection itself. – Elizabeth Pochoda

The following essay is excerpted from Black Dolls, recently published by Radius Books and the Mingei International Museum.

Miniature trains and boats; animals and picture books; balls that bounce and tops that spin: these toys belong to non-human worlds. Dolls are the only toys made in our image, the only human-like creatures children are given dominion over. You, the child, are the creator of an ordered existence: a miniature kingdom that can imitate or disrupt the logic of your everyday life, the life conceived of and run by adults. They do what they want with you. You do what you want with the doll. You’re loving, you’re fickle; you’re imperious and stern. You coo and comfort the doll, you hurl it down and spank it. You dress and undress the doll, as you are dressed and undressed.

You speak to it, you speak as it, you speak for it. So much of your time goes to courting and evading adult attention. You reenact all this with your dolls. You try to improve on it giving them what you don’t get (not enough of anyway) from those humans who rule your life.

How do these rituals play out when your doll is made in the image of another race? When at the same time, on some distant or not distant enough horizon, Race—black, white, Negro, Caucasian, African American, European American—is a barrier and a mystery. Race holds such conflicted intimacies and alienations; mistrust, longing, fear, attraction, disdain, and, if we must say hate, we must also say love, knowing how many shades of each exist. Who are you playing with when you play with, live with, a doll of another race? One you share a private space with, while parents, teachers, neighbors busily impose their expectations and inhibitions on the doll and on you.

So many of the children in the 19th- and early-20th-century photographs are holding, clutching, dangling, clinging to a doll of That Other Race. How do we, their descendants, place ourselves in the stories they suggest?

Reader, I am the descendant of those little brown girls who stand in photographers’ studios dressed in meticulously nice clothes, holding meticulously well-dressed white bisque dolls (probably made by Germans or Italians in their cottage-industry workshops).

A small, sturdy brown girl on one cabinet card [Fig. 4] wears a coatdress trimmed with grosgrain ribbons. She leans against a chair in W. P. Kendall’s studio somewhere between 1875 and 1890; the chair’s tassels echo her shiny ringlets. In one hand she holds a white doll in a white dress; in the other she’s holding the handle of the little doll’s carriage. She appears to have taken command of her possessions and her persona.

The Carrington daughter of Norwich, Connecticut, has browner skin and fuller features [Fig. 6]. Somewhere between 1910 and 1920 her parents dressed her in a white fur coat and an Edwardian bonnet, black like her boots, but embellished with white ribbons and affixed to her chin with a vast white bow. She has the resigned look children get when they’ve been told not to move or misbehave in any way. This is the image of a child being taught to represent the Colored Race and its women—no, its ladies—at their best.

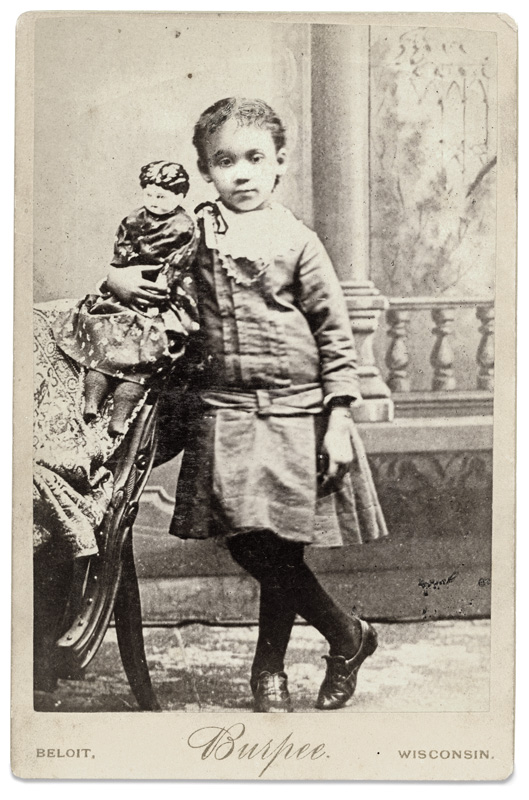

I breathe easier in the presence of the little girl from Beloit, Wisconsin [Fig. 7]. Her stance is breezy; she crosses one foot over the other with boyish aplomb. The matronly white doll is her prop; she looks confident of her ability to impose on the camera—and impart to us—her own sense of what the world should be and what she has to offer it.

How I want to evade the legacy of this racial doll narrative! It’s tinged with the abject: here we are, little brown girls, all craving pink and white dolls.

In 1953 or 1954 (I’m sure the significance of the years will escape no one), I was 6 or 7; a cossetted little Chicago girl with a collection of white dolls. My great-grandmother, Sarah Trotter, and her sister, Ada Sykes, sent me a brown doll for Christmas. They lived in St. Louis and belonged to the generation of Negro girls born in the 1870s, who may have played with both store-bought white dolls and homemade black dolls. The one they sent me was neither: it was a contemporary, ostensibly realistic model, maybe a Ginny Doll, the facsimile of a nice little girl next door with a pert brown face, sweetly curling hair, and a full-skirted, puff-sleeved blue cotton dress. Coached by my mother, I wrote a polite thank-you note. I studied the doll for several days. I did not name her or play with her. And after several months she disappeared. My mother must have donated her to Provident Hospital, where ailing Negro children could choose to (or have no choice but to) play with her.

By not wanting Aunt Ada and Mama Trotter’s doll, I showed I did not want their history—not then. That history, that doll, stopped me from feeling wholly entitled to my sheltered life. The white dolls were mine and when you play with dolls, the question is (to rephrase Humpty Dumpty), who is to be mistress? I was their mistress. I enjoyed my white dolls, I enjoyed having what other little American girls had. Did I envy their impeccable Anglo Saxon looks? I did. But that was in the back of my mind. A brown doll would have pushed it to the front.

Now I turn the pages of this book and study the photographs of black children who stand before modest rural homes or schools holding white dolls. Barefoot boys, some of them; girls with scuffed shoes whose dolls are better dressed than they. These children, I remind myself, had much more to contend with than the abject doll narrative. Poverty and prejudice; proscription and derision. This grim thought propels me to the photographs of dolls made to be servants (nurses, mammies, housekeepers), held in the arms of prosperous-looking white children who will employ their human counterparts (doubtless some of the children who stand before those modest rural homes and schools).

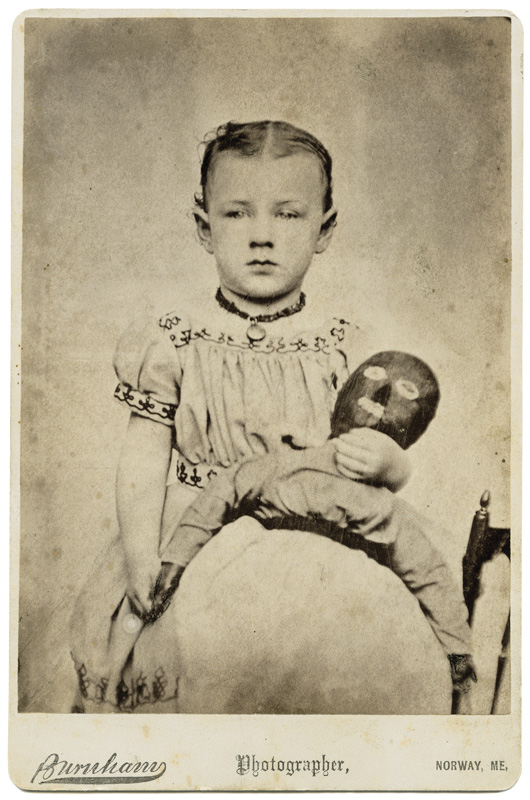

Dolls have no rights a human is bound to respect. These black dolls represent people with few rights a white person was bound to respect. This, I think, is why I’m drawn to the photograph of a young white girl with pointed ears, her short hair parted in the middle like a boy’s [Fig. 9]. She holds a moon-faced black doll with wide white eyeballs and an unsmiling white mouth. Both have mask-like faces. Both deviate from standard white prettiness. Both are stern, willful presences.

But it’s time to leave a world where dolls are in thrall to people like us.

It’s time to enter their world, so scrupulous, so sumptuous! Behold them, framed by white and black space, released from our needs and demands. What intricate forms and features their anonymous creators gave them! What clothes!

They induce a state of rapture in this viewer.

They say: I am black and comely in all conceivable ways. I am varying shades of black, brown and beige. I am decorous, impish, fearsome, and wise.

They say: I have my vanity. (Gaze on my dark, lustrous eyelashes and smartly-coiffed hair.) They say: I have my griefs. (Count the tears on my cheeks.)

My mouth is a narrow red thread; my mouth is a pale peach, full and slightly downturned, matching my straw hat and my dress with its crocheted top. My nose is a bulbous lump, a refined triangle, a curved line; hooked or slim with delicate flaring nostrils. My yarn, bead, or button eyes hold your gaze and gaze past you.

Fashioned from cloth, leather, wood, and occasionally even coconut, some of these dolls have the mask-like abstraction of African sculpture. Others have the exuberant detail of those creatures (human, animal, mythical) that populate folk and medieval art.

While none have the calculated mimetic realism of factory-made dolls, many have faces that evoke and honor the black people photographed here. Some are hyper-stylized, though, like visitors from a spirit world. Look at this black totem with blue eyes and ivory brows, naked except for a thin beige collar and red boots. Look at this flame-red, wild-haired woman with black legs and feet. Toys, idols, familiars: What runic messages do they convey?

As for the clothes, had William Blake seen them, he might have written:

Little doll who made thee made thee / Dost thou know who made thee… / Gave thee clothing of delight, / Softest clothing wooly bright; / (Velvet, poplin, silky bright.)

These tailors and dressmakers ignored the dictum that Negroes should wear quiet colors, muted (or no) patterns, and minimal accessories. Look at the daring blend of fabrics and patterns, the color palette (primary and pastel, earth tones, shades of beige, cream, and ivory); the cunningly placed pockets; the buttons, carved and patterned; the spiffy pleated shirtfronts; the trim (some bold, some dainty) on hats, collars, and petticoats; the bodice with jet beads (or blue-green lace if you prefer). Black dolls wear sailor suits and frock coats; natty vests and ascots; woolen capes and pale linen dusters; dresses with cinched waists, dropped waists, and Empire waists; bonnets, caps, and fedoras. The refinement of craft meets the wit and daring of art.

Touchingly, the dolls show the physical toll of years, decades, centuries spent in trunks and cabinets, on dressers and bookcases, hauled from one craft fair to another. Wood and leather crack, fabric shreds and fades. Small holes and tears appear on limbs and faces. Some look like scars or calluses; some even look like vitiligo spots. But most look exactly what they are: visual testimony—(the tobacco brown nose with a pale patch down the middle, the black face with white shadows)—that race is a construction.

So is art. Art is a construction. The dolls in the photographs have outlived the proscriptions and conventions of race, class, and gender. Those in the historical photographs couldn’t: they belonged to us and we belong to history. But art is history too. See these two histories side by side: it’s a revelation. They invite us into a space where objects, stories, and people are made and remade; restored and reenvisioned every day of our lives.

MARGO JEFFERSON is a former theater critic for the New York Times and a professor at Eugene Lang College The New School for Liberal Arts.