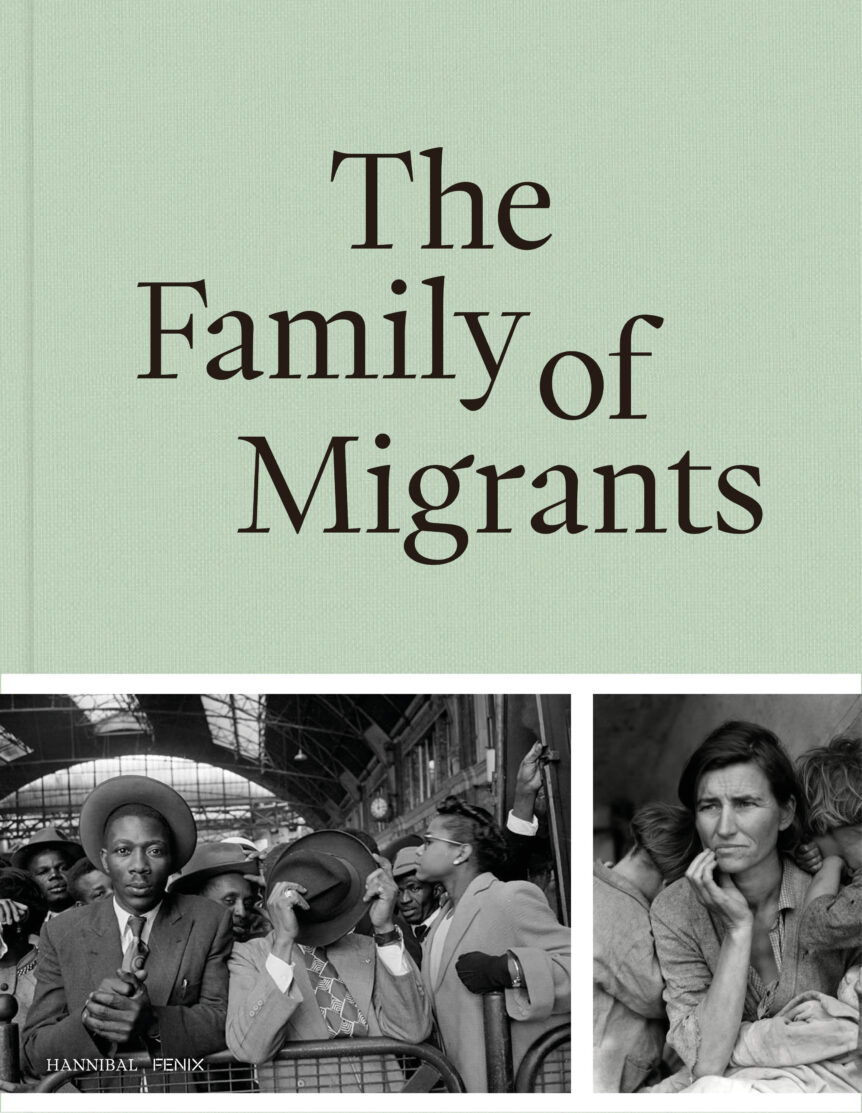

There is hardly a figure whose mere existence provokes more contention than the migrant. Emerging as the criminal “illegal” for some, the tragic refugee for others, or the aspirational immigrant for still more, the migrant occupies disparate spaces within the public’s imagination. The Family of Migrants (Hannibal Books) underscores the poignant pitfalls of reducing migrants to such clichés.

Indeed, through an impressive selection of 193 photographs ranging from the nineteenth century to the present day, the book traces rich narratives of migration for each individual it captures. Where some flee out of necessity, others seek new opportunities. No story is the same, and yet, one can trace overarching themes of joy, loss, family, sorrow, and hope throughout.

The Family of Migrants masterfully weaves decades worth of history and creative inspiration into a fluid, threepart structure: “Departure,” “Journey,” and “Arrival.” Photographs by Dorothea Lange, Yasuhiro Ogawa, and Sergey Ponomarev, among others, appear alongside poetry, creative essays, and speculative fiction that muse on the physical, emotional, political, and relational toils experienced by those on the move.

Far from unwelcome interruptions, these editorial interludes offer resonant insights from knowledgeable scholars, many of whom have their own migration stories. Indianborn British restaurateur Asma Khan, for instance, speaks to the immense anxiety over deportation that immigrants endure as they set down roots in their new homes. The result is an immensely moving story about migrants as people, not things to be counted, or clichés to be consumed.

As the executive director of World Press Photo, Joumana El Zein Khoury notes, The Family of Migrants’s “ambition is to showcase both the role that images in the media have played in reinforcing stereotypes while also trying to change those stereotypes by offering other perspectives and voices.” The first section, “Departure,” captures the deep complexity of the familiar designation of “home.” Ernest Cole’s 1960 photograph of Black South Africans crammed into a segregated train during apartheid rule appears alongside Robert de Hartogh’s photograph of a Moroccan man packing his car to work in the Netherlands. The Hartogh caption indicates that the man plans to return home for the summer. For some, “home” is a site of surveillance and exclusion; for others, it is a place left behind but not forgotten. Notably, “home” is not, as the familiar, xenophobic chant often claims, a place migrants can easily “go back” to.

While The Family of Migrants excels at emphasizing the plurality of migrant experiences, it also draws attention to meaningful silences in migration photography. A photo taken by David Moore in 1966 captures an enormous ship bustling with people as they arrive at Sydney Harbor. For years, the photo was thought to symbolize European migration to Australia. Only later was it revealed that the ship teemed with Australian vacationers, along with two immigrants from Lebanon and Egypt. Moore’s photograph points us to the dangers of reducing people’s stories to easily consumed visual heuristics. Without sufficient context, one may feel emboldened to fill in the gaps themself.

However, it is imperative to remember that these are photos of real people with real histories, experiences, and aspirations. The “creative liberties” we take with their stories—while sometimes resulting in a humorous misrecognition of partiers on vacation—can and do have dire consequences for migrants.

Ultimately, The Family of Migrants asks its readers to refuse the flattening gaze. It presents human beings deserving of dignity, not “illegals” hellbent on crime. It advocates compassion, not sensationalism, in media representation of migrants. Perhaps most importantly, The Family of Migrants asks not only where migrants are going, but what we choose to see when they arrive.